"So Jaco Pastorius and Joni Mitchell walk past and ask, ‘Hey, is there a party here?’." The story of Italian prog legends PFM

Newly signed to InsideOut Music, Italian prog legends Premiata Forneria Marconi returned with new album Emotional Tattoos in both English and Italian

Italian prog legends signed to prog label InsideOut and released the bi-lingual Emotional Tattoos in 2017. Prog visited the band in their Milan studios to find out more and to discuss how they’re still challenging themselves nearly 50 years on, what it was like being mentored by Greg Lake, and that time they ate spaghetti with Joni Mitchell…

In the wilfully obtuse world of prog, artists are not often known for doing things the easy way. But while others of a similar mindset might challenge themselves in terms of instrumental technique, performance or lyrical concepts, Italian prog pioneers Premiata Forneria Marconi set themselves a slightly more unusual task while making their new studio album (or, as we’ll explain, albums) Emotional Tattoos.

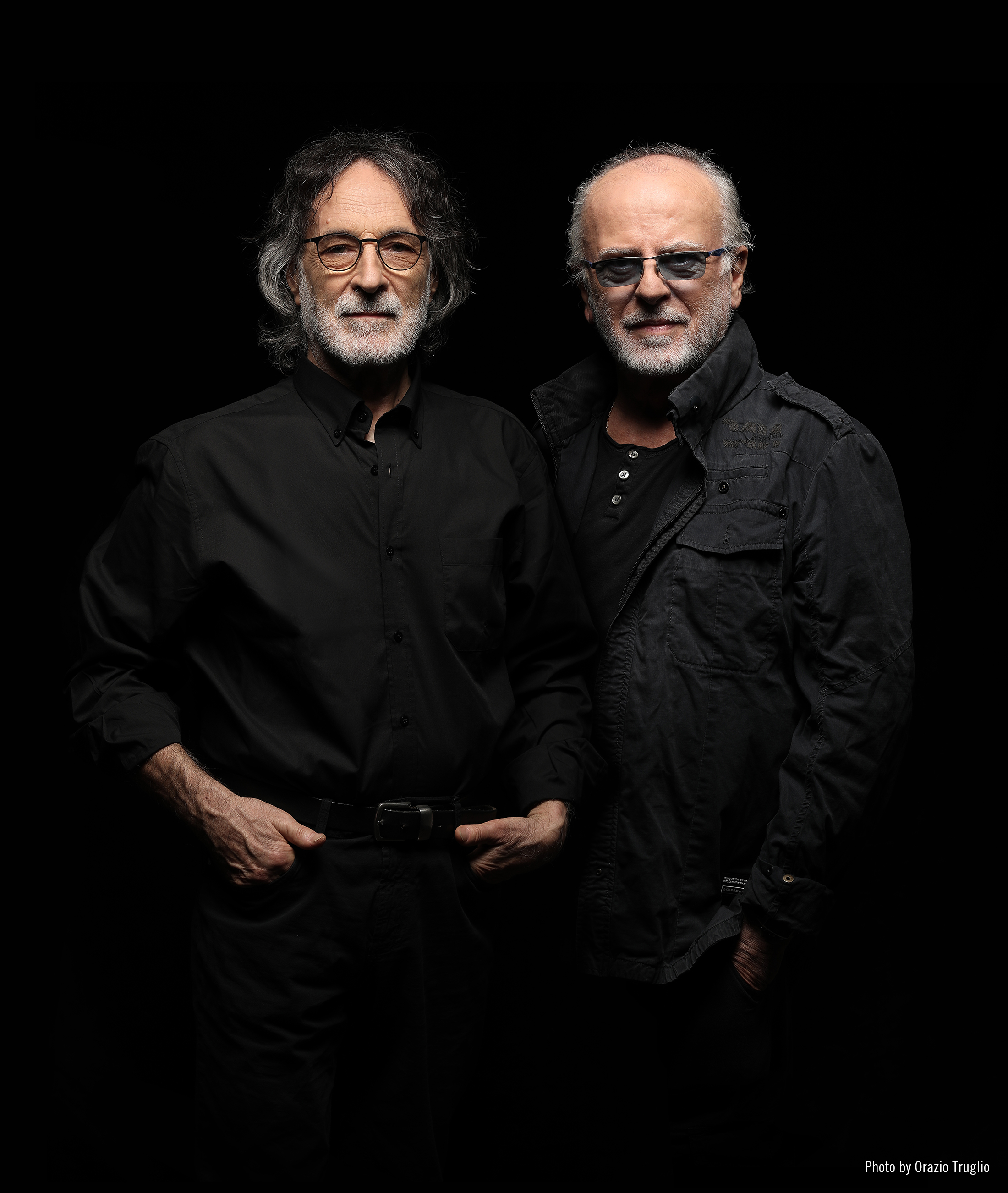

“This time we decided to do two different records,” explains singer and drummer Franz Di Cioccio. “The same music, but one in Italian and one in English. It’s the better way to understand what we want to sing about.”

“We made them together at the same time,” says bass player Patrick Djivas. “First the Italian then the English, and sometimes the two were racing each other to be finished.”

However, the lyrics on one album don’t necessarily correspond to the other.

“How can you say the same things to Italians or to Americans or British people?” asks Djivas. “Especially as Italy has a way of thinking that is so different to the rest of the world.”

To demonstrate, the pair sit Prog down in their Milan studio and play the new album to us. In English, we should add.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The atmospheric 7/8 piano figure of Morning Freedom, renamed Oniro for the Italian version, rings from the speakers, and when we come to the chorus after which the English version is named, Di Cioccio explains: “We had the English phrase for the chorus first [breaks into song]: ‘Moor-ning Freeee-dom’. If we had translated that directly into Italian, it would be [sings again] ‘Mat-i-no di li-ber-ta…’ so it would be a completely different rhythm to the line and feel completely different, not reflecting the emotion it is supposed to show.

“So in Italian it’s ‘sogni liberi’ – ‘make the dream free’. From there we build a different lyric. It’s a difficult exercise, but we like it that way.”

Fans of the band since their acclaimed 70s output will be aware that making records in Italian and English is not new for PFM. But back when they made career-defining albums such as Photos Of Ghosts, they could rely on the services of one of prog’s most celebrated lyricists to bring their visions to life in a foreign tongue.

“We had Mr Pete Sinfield writing lyrics for us,” says Djivas, “and he was really heavy on us until we sang it really good in English. But this time Franz did a good job – I think it sounds pretty natural.”

They also still get their message across. And in both English and Italian, the themes are similar: There’s A Fire In Me and It’s My Road offer up the power of music as a force to heal in the face of a fractious world; The Lesson takes a “no pain, no gain” philosophy to the challenges of life and love; and opening track We’re Not An Island sounds remarkably apposite to anyone wondering what’s to become of the UK post-Brexit and the US post-Trump, even though Djivas and Di Cioccio insist they had less specific social sentiments to impart.

Most striking of all, though, both lyrically and musically, is A Day We Share, which surveys a global landscape in search of common ground, despite observing scenes such as: ‘El Paso, Texas, almost in the middle of the night, watching the wall, waiting for the call to tear it all, another Berlin until we win…’

The six-minute journey starts with rhythmic punches of acoustic guitar and florid keyboard swoops and swirls, before stepping up the drama with a mesmerising battery of staccato rock riffs, then unexpectedly sidestepping into a more groove-based, almost rap-like section of stream-of-consciousness observation. Then the curtains are thrown open onto a big, anthemic chorus and a joyfully upbeat celtic-tinged denouement.

Reports of PFM mellowing their approach in their old age have, it seems, been exaggerated. “We wouldn’t want to play like we did back then,” says Djivas. “It would bore us to death. But we still like to challenge ourselves.”

Only the 71-year-old Di Cioccio remains from their founding line-up of the band, which formed when the Milan‑based quartet of session musicians calling themselves I queli (which is roughly translated as ‘those guys’) expanded to a five-piece in a bid to explore more adventurous musical avenues, with an ambitious name to match.

Patrick Djivas would join their ranks a couple of years later on bass, but first, they had to establish themselves within a highly sceptical local industry.

“We were excited by the music we were hearing from abroad at that time,” says Di Cioccio. “King Crimson, Jethro Tull, Ekseption… we just got the feeling the wind was changing in our favour.

“So we changed our name and began to move to a more improvisational style. But people just couldn’t understand why we called ourselves Premiata Forneria Marconi. Award-winning bakery? When we played our first show under that name, the promoter wouldn’t even announce us! We were opening for Deep Purple, and support acts weren’t that common in Italy then. He thought if he announced a band that wasn’t Deep Purple, just a local band, everyone would just throw things at us, and if he told them we were called Premiata Forneria Marconi, they would just think, ‘What the hell is this?’ So he just refused to introduce us.”

Furthermore, he didn’t even tell the venue technicians to turn the lights on for the band, so as they stepped onto the stage in darkness, the only option, as the enduring cliché would have it, was to let their music do the talking.

“Back then we used to play covers, like most bands do at first, and we began playing 21st Century Schizoid Man,” says Di Cioccio. “We used to play the part where they stop and start, the really complicated bit, just looking at the ground, not at our instruments, just to make people a bit shocked that we could play it without looking, yet perform it perfectly. At the end the promoter sees the reaction for us, gets up on stage and says, ‘This is Premiata Forneria Marconi. You will be hearing a lot more about them!’”

He wasn’t wrong, and over the coming months, numerous other like‑minded compatriots would emerge with similarly avant-garde sounds, many of whom just happened to have curiously elongated names, such as Banco Del Mutuo Soccorso and Biglietto per l’inferno. The Italian prog scene was snowballing, and its leading lights were about to get a major break.

“Greg Lake was given a tape of us when ELP played in Italy, and after a month, he calls our manager Franco Mamone and he says, ‘Hey, I can’t believe these guys played that song [Schizoid Man] like this.’ He says, ‘I want to see them playing it because I used to play with King Crimson and I know how hard it is.’”

A London showcase gig was set up and, duly impressed, Lake signed PFM to his new label Manticore. Their new mentor, keen to introduce them to the English and American markets, hooked the quintet up with erstwhile King Crimson lyricist Pete Sinfield. But Sinfield and Lake had a suggestion to make first.

“They said, ‘English speakers can’t pronounce Premiata Forneria Marconi’ – they would always put the wrong emphasis on the syllables – Prem-eee-tur Forn-eerie-yur Marconi or something – people knew Marconi because it’s a famous name but otherwise people struggled with it, so we said, ‘We’ll just call ourselves PFM.’”

With Sinfield, they set about turning songs from their second album, Per un Amico, into an English language release, Photos Of Ghosts, beefed up with a reworked instrumental from their debut, Storia di un Minuto.

The finished article juxtaposed dazzling, urgent bursts of jazz rock with pastoral, classically tinged folk rock, warped psychedelia and ebullient synth-heavy prog.

Helped by Celebration becoming an FM radio hit, Photos Of Ghosts made them the first Italian act to enter the Billboard Top 200 album chart.

By that time, Djivas had joined to reinforce the sound of a band that was touring incessantly and thrilling crowds with improvisation-heavy shows of the kind that had already made the Grateful Dead famous. And how better to capture that magic than with a live album?

“ELP had hired a mobile studio in Central Park, but something happened and they couldn’t record that day,” says Di Cioccio. “But they had paid for it anyway, so they came to us and said, ‘Tomorrow we have the mobile studio. Do you want to record your show?’

“We agreed, but then pretty much forgot about the recording, so we played normally, improvised pretty much the whole show, and that really made it so much better I think. Sometimes if you’re aware you’re being recorded live, you’re trying not to make mistakes, and it’s turns out a bit stiff.”

That recording formed part of Cook, a defining album for PFM, retitled and repackaged as Live In The USA for its European release.

By that point, it felt like there had never been a better time to make music. Our heroes had found a home from home just off LA’s Sunset Strip, on Alta Loma Road, as referenced in the extended jam Alta Loma Five ’Till Nine that they created there.

They would also stay at the Sunset Marquis hotel.

“All the musicians stayed there,” Djivas recalls. “There was a party every night.”

“I remember one night,” says Di Cioccio, “Jaco Pastorius was recording Hejira with Joni Mitchell and they come in and he smells we are cooking in our room. They asked, ‘Hey, is there a party here?’ We say, ‘No, we’re cooking spaghetti. Want some?’ So Joni and Jaco come in and we’re hanging out and Patrick’s playing bass with Jaco. It was a great time.”

Things would turn slightly sour in the US, however, after their 1975 album Chocolate Kings, featuring newly recruited former Acqua Fragile singer and fluent English speaker Bernardo Lanzetti. It featured a cover that didn’t go down too well in the ever-patriotic States.

“The cover was an American flag with chocolate inside, but the flag wrapper has been thrown away,” Djivas explains. “We really didn’t understand the weight of an Italian band in the US making fun of America.”

Meanwhile, a focus on foreign territories meant the band didn’t even put out an Italian version of the record, meaning their profile also slipped back home.

1977’s release Jet Lag would prove to be their last sung in English, as Lanzetti departed, with drummer Di Cioccio later taking the Phil Collins route to the lead singer’s mic, and they concentrated on rebuilding their fan base at home. A pair of records backing Italian folk troubadour Fabrizio De André helped, and they consolidated their position as one of Italy’s best-loved rock acts.

But it’s been over a decade since their last album of new compositions, and their task wasn’t helped when their guitarist Franco Mussida called it a day with the band in 2015, leaving the rump of Djivas and Di Cioccio in creative charge of the band.

But every cloud…

“One good thing that happens when someone leaves the band is that you can choose his replacement,” says Djivas. “The new guitar player [Marco Sfogli] is from Naples and Neapolitans have a lot of heart, they are very emotional people. So he’s a ridiculously good technical player who can do anything, but he also plays great melodies and we love that.”

And while Sfogli is barely half the age of his new bandmates, he is one of

a generation of younger prog players that continues to carve out a strong reputation across Europe, helped by a thriving scene back home – covered, we might add, by the Italian equivalent of this magazine, Prog Italia. So do Djivas and Di Cioccio hear their influence among the current generation of Italian bands?

“No, I didn’t hear anything in the last year,” says Di Cioccio, “and that’s deliberate, because I don’t want to be influenced. Writing songs, arrangements, writing lyrics in Italian, writing in English – it takes focus!”

“I’m the same,” says Djivas. “They cut off the lights in my house twice because I didn’t pay the bills. Not because I couldn’t, but because I was so focused on the album!”

It’s that no pain, no gain philosophy in action, though, and the diligent work of Premiata Forneria Marconi’s lead pair in producing a record in two languages has borne fruit, in the shape of an album (albums, in fact) that can stand proudly alongside the records with which they made their reputation 40-odd years ago.

“For us, the album is a positive journey,” Di Cioccio concludes as a jazz piano solo ends the final track It’s My Road. “We start the album with You’re Not An Island, and then the last lines are: ‘I’m feeling like a god!’”

And who can deny him such feelings? After all, in terms of European prog at least, PFM deserve a bit of deification.

Johnny is a regular contributor to Prog and Classic Rock magazines, both online and in print. Johnny is a highly experienced and versatile music writer whose tastes range from prog and hard rock to R’n’B, funk, folk and blues. He has written about music professionally for 30 years, surviving the Britpop wars at the NME in the 90s (under the hard-to-shake teenage nickname Johnny Cigarettes) before branching out to newspapers such as The Guardian and The Independent and magazines such as Uncut, Record Collector and, of course, Prog and Classic Rock.