“We’d jump off roofs or off bridges into water, knock the wind out of ourselves and almost die. We lived very aggressively because that’s who we were”: The story of Mate. Feed. Kill. Repeat. – the secret debut album that started Slipknot’s ascent

Before Corey Taylor and before the nu metal takeover, Slipknot launched their career with a DIY release that put the Des Moines scene on notice

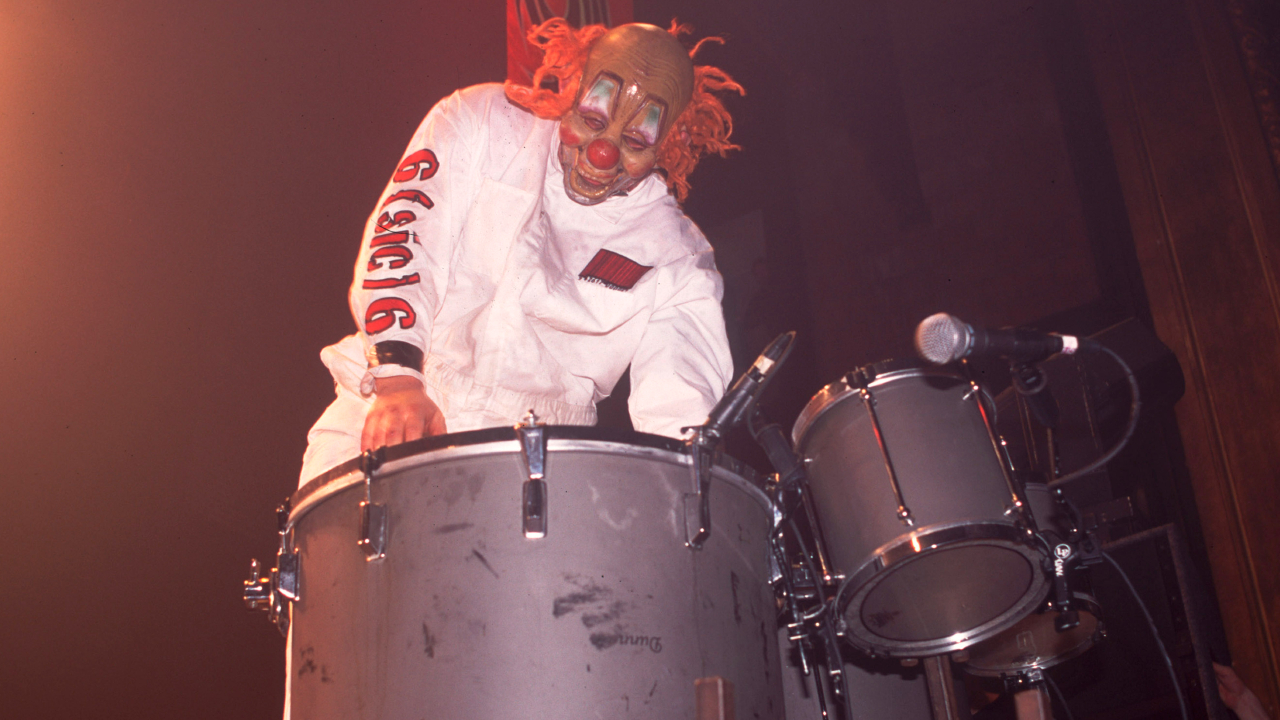

Shawn ‘Clown’ Crahan can remember the point when he knew that all the blood, sweat and pain that he’d invested into Slipknot had paid off.

It was the end of May 1999 and the band were playing that year’s Ozzfest, sandwiched between industrial metal heroes Static-X and rap-rock B-listers (hed)p.e. on the second stage. Their self-titled album was a month away from release, but the buzz surrounding this masked-and-boiler-suited nine-piece from the Midwestern backwater of Des Moines, Iowa was growing louder by the day.

“We used to watch people running from watching a main-stage band to come see this new thing called Slipknot on the second stage,” says Shawn today. “I remember them sprinting to get there. I knew it was the punch in the face the whole fucking world was waiting for.”

The album that emerged swinging and screaming into the world a month later would launch Slipknot into orbit, but it was far from the beginning of the story. It wasn’t even their first record. That had come three years earlier, in 1996, back when they had a completely different singer and a discernibly different sound. Their debut album, Mate. Feed. Kill. Repeat., might not have changed the world like its celebrated follow-up, but without it, what came afterwards – for Slipknot and for metal – would have shaped up very differently.

Like most mid-sized cities across the US, Des Moines has its own musical ecosystem. Back in the late 80s/early 90s, thrash and death metal ruled the handful of clubs that put on rock gigs, and the bands that formed and fell apart were made up from a hardcore cast of local musicians.

Anders Colsefni was one such musician. He’d started playing drums in fourth grade, and by 1990 he was a member of Vexx, a local band that also featured LA transplant Paul Gray on bass.

“Paul was my biggest influence when he came into the band,” says Anders today. “He brought the knowledge and the enthusiasm, and he was the most social of all the people on the metal scene. He was the sort of person who, when he got his meagre paycheck from working at the gas station, would go down to the bar and spend it all buying people drinks. He was loved around that scene.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Shawn Crahan was another face on the Des Moines scene. His band, Heads On The Wall, played heavy alternative rock that drew on Jane’s Addiction, Primus and Helmet. “The first night we played with them, Shawn threw a bunch of 80s albums into the audience and told us to break them,” says Anders. “Journey, stuff like that. He also threw out Sailing The Seas Of Cheese by Primus, unopened. He said: ‘Don’t break that.’ I still have it.”

The two men were similar in looks, physique and worldview – “We had the same kind of dark, anti-social way of looking at things,” says Anders – and they inevitably gravitated to each other. By the end of 1992, they were discussing making music together.

“We got talking: ‘Hey, do you want to try something with drums – just beat on them?’” says Anders. “We got together and put on some moody lighting and started jamming, getting away from what people normally did.”

The very first song they wrote together was one that eventually gave the band its name: Slipknot. Another early track was Painface, its name stemming from an act of physical violence that presaged one of the things the band would become notorious for.

“Painface was a term Shawn and I came up with before we even got the band together,” says Anders, who doubled up on percussion and vocals. “We were coming up with samples. One of the things he wanted me to do was record me punching him. I’d say, ‘Show me your pain face’, he’d go, ‘No’, then I’d punch him. That was his weird little thing.”

“Let’s just say that I provided how people felt at that time in life,” says Shawn. “We ran with a serious crowd. We’d jump off roofs or off bridges into water, knock the wind out of ourselves and almost die. We lived very aggressively because that’s who we were.”

With Paul Gray and guitarist Patrick Neuwirth onboard, the band recorded a demo tape, later christened The Basement Sessions, in April 1993. A second tape followed a month later, but by the end of the year the project had fizzled out.

It would be almost two years before Anders and Shawn reunited to give it another shot. They persuaded Paul Gray to come back to Des Moines from LA, where he had relocated, and brought in guitarists Donnie Steele and Josh Brainard. Joey Jordison, former drummer with thrash band Modifidious and the night manager of a gas station, signed up to provide extra firepower.

This new entity made its live debut on December 4, 1995, under the name Meld. The gig, put together as a showcase by local recording studio SR Audio, was held in the basement of Des Moines club The CroBar. “There weren’t an awful lot of people there,” says Anders with a laugh. The band entered SR Audio’s studio to begin work on the songs that would make up Mate. Feed. Kill. Repeat. Soon after, on Joey Jordison’s recommendation, they renamed themselves after the very first song Anders and Shawn had written: Slipknot.

The band’s name wasn’t the only thing that had changed. Shawn had come up with the idea of wearing a mask for performances, while Anders opted for electrical tape wrapped around his head.

“Shawn and I were in the studio creating samples for the end of Mate. Feed. Kill. Repeat.,” says Anders. “For one of the samples at the end of Killers Are Quiet, I wrapped duct tape around his head and we recorded me ripping it off. He looked distorted and mutated with the tape. I thought, ‘That’s cool – I’ll do that onstage.’”

Their first gig as Slipknot was on April 4, 1996 – Anders remembers the date, as he’d been a pallbearer at his grandmother’s funeral that day. Many of the familiar elements of later Slipknot shows were already in place, not least the air of violent intimidation that surrounded the band.

“We came in through the front and walked through the crowd, just dead-cold staring at people like we didn’t know they were there,” he says. “We got onstage and shocked the hell out of everybody. Sprayed sparks all over the place. I was cutting myself with a razor, bleeding all over the place. It looked pretty violent. For me, it was an extremely emotional experience.”

If Slipknot’s early live shows were a form of catharsis, then recording the album was a different matter. Anders describes the experience as “a grind”.

“We were trying to make a sound that hadn’t really been made yet,” he says. “We would come up with these incredible, bone-crushing sounds, but then you’d play it on a regular stereo and it would just fart everything out.”

Nailing their wall of noise wasn’t the only thing that prolonged the recording process. There were creative tussles, departures (Donnie Steele quit, due to his Christian beliefs jibing with the songs’ subject matter), not to mention mounting debt. Some reports put the cost of recording the album at $40,000. Anders says it was closer to $16,000 – significantly less, but still a hefty amount for a bunch of broke musicians with families to support.

“It was Shawn with his credit cards that got that album made,” says Anders. “And him buying the Safari Club and turning it into our home club, that brought money in there.”

The Safari Club played an important part in Slipknot’s development. Originally a blues bar named Baggs, Crahan had earmarked it at as the focal point for the band.

“I wanted somewhere in Des Moines for us to play regularly, and it was perfect. I knew the owner, and every time Slipknot played, I’d go in and clean it. One day, he looked at it and said, ‘I’m tired of coming down here and watching you clean my place. I’m thinking of opening another bar. Why don’t you just buy the motherfucker?’”

Shawn pulled together the money with help from his parents. The rest of the band gave Clown money towards their share of the debt whenever they could. Anders paid off his part by pouring sand and concrete into the basement of the club and helping keep the club’s books.

Slipknot finished the record in late summer, seven months after they started it. Today, Anders Colsefni still sounds emotional when he recalls the first time he heard it in full.

“I thought that we were going to be touring with Slayer someday,” he says. “I really felt we had something that was gonna hit it. I’m actually getting goosebumps thinking of it now.”

Mate. Feed. Kill. Repeat. was released on October 31 that year – Halloween. Just 1,000 copies were pressed (original copies can fetch $700+ on eBay). While the song Slipknot – later reworked as (sic) – was more indebted to thrash and death metal, and Do Nothing/Bitchslap even took a detour into funk-metal territory, the 10-minute percussive barrage Killers Are Quiet and early versions of Tattered And Torn and Only One are still recognisable as Slipknot in all their confrontational glory. It was no coincidence that the album’s initials read like an abbreviation of ‘Motherfucker’.

The opus instantly pushed Slipknot to the forefront of Des Moines’ metal scene. The only other serious competition were alt-rockers Stone Sour, the band featuring future Slipknot guitarist Jim Root and singer Corey Taylor. “They were a different style,” says Anders. “Corey was a singer, I was way more growly. We beat them in a Battle Of The Bands once. But competition and all that stuff? I think it’s a bunch of bullshit.”

From their base at the Safari Club, Slipknot built a dedicated local following. Shows featured the Clown-masked Crahan and a wolfskin-loincloth-and-duct-taped Colsefni shooting sparks from their instruments, before the latter unleashed his death growls on a stunned audience. As word of their shows spread, they came to the attention of Roadrunner Records, and subsequently Korn producer Ross Robinson.

“Him and his manager came to my house on a Friday to watch pre-pro [pre-production], then on Saturday they came to an all-ages show at the Safari Club on Saturday, about 575 kids there,” says Shawn. “And Ross Robinson said ‘yes’ to working with us right there.”

Slipknot’s future looked bright, but there would be one major casualty of their ambition. In the summer of 1997, Anders Colsefni took his family to Minnesota for a week to visit relatives. When he came back to Des Moines, the band called him to a meeting at the bar.

“Roadrunner were worried about the growly vocals,” he says. “They had been discussing bringing in Corey, and that’s what happened. They had him record all over my vocal tracks at SR Audio. When I got to the bar, they just jumped and said, ‘Hey, this is what we did – we want you to be back-up singer.’ I was, like, [skeptical], ‘OK…’”

Anders stuck it out for a few more gigs, but he felt betrayed by his friends, especially after everything he’d put his family through – the rehearsals in his basement, the debt, everything. Opting to go out with a bang, he announced his departure onstage at a Slipknot show in December 1997.

“I didn’t tell anybody, except my wife at the time,” he says. “I shaved my eyebrows off and everything. When I got off the stage after I said it, Jim Root – who was the guitar player of Stone Sour – came over and gave me a huge, huge hug. ’Cos he understood.”

“I understood how hard it was for him to go from being the lead singer in band that was very popular in Des Moines to just being the other percussionist,” says Shawn Crahan. “Andy’s got one of the best death growls you’ll ever hear in your life, and I always wondered what that would have been like with Corey. And Corey wanted to do that. But it was a pride thing, no one was communicating, the dream was right on hand…”

He sighs at the memory. “It was very hard.”

The departure of Anders Colsefni marked the end of the first chapter in the Slipknot story. It took him several months to get over the feelings of anger and betrayal, though today he’s on good terms with his former bandmates.

“If I’d have stuck with it, I would have a lot more money – I wouldn’t have to worry about it like I do now,” he says. “But at the same time, I’d probably be addicted to whatever drugs were available, because I have the ability to become addicted to anything. So staying away from that stuff has probably kept me alive.”

Post-Slipknot, Colsefni formed a new band, which he named Painface after the song he had written with Shawn Crahan. After they fell apart in the early 00s, he passed through a handful of other bands, before reactiving Painface a few years ago. Today, he has plans to write and record new songs under that name. He has another band, All That Crawls, with his son Josh. “That’s acoustic stuff, mellow and sad,” he says. “I don’t like writing happy songs.”

For Shawn Crahan and Slipknot, the journey has been more visible but no less turbulent. The run of successful albums has been punctuated by periods of internal turmoil, reaching a nadir with the death of bassist Paul Gray in 2010 and the departure of Joey Jordison in 2013.

“I believed in Slipknot right from the beginning,” says Shawn now. “Every day I woke up, I felt like I had a purpose. I was 26 when I started the band, I had two kids at the time. But something called a dream was raising its head, and it felt amazing. And when that happens, you just don’t let go of it.”

This article originally appeared in Metal Hammer issue 306, February 2018.

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.