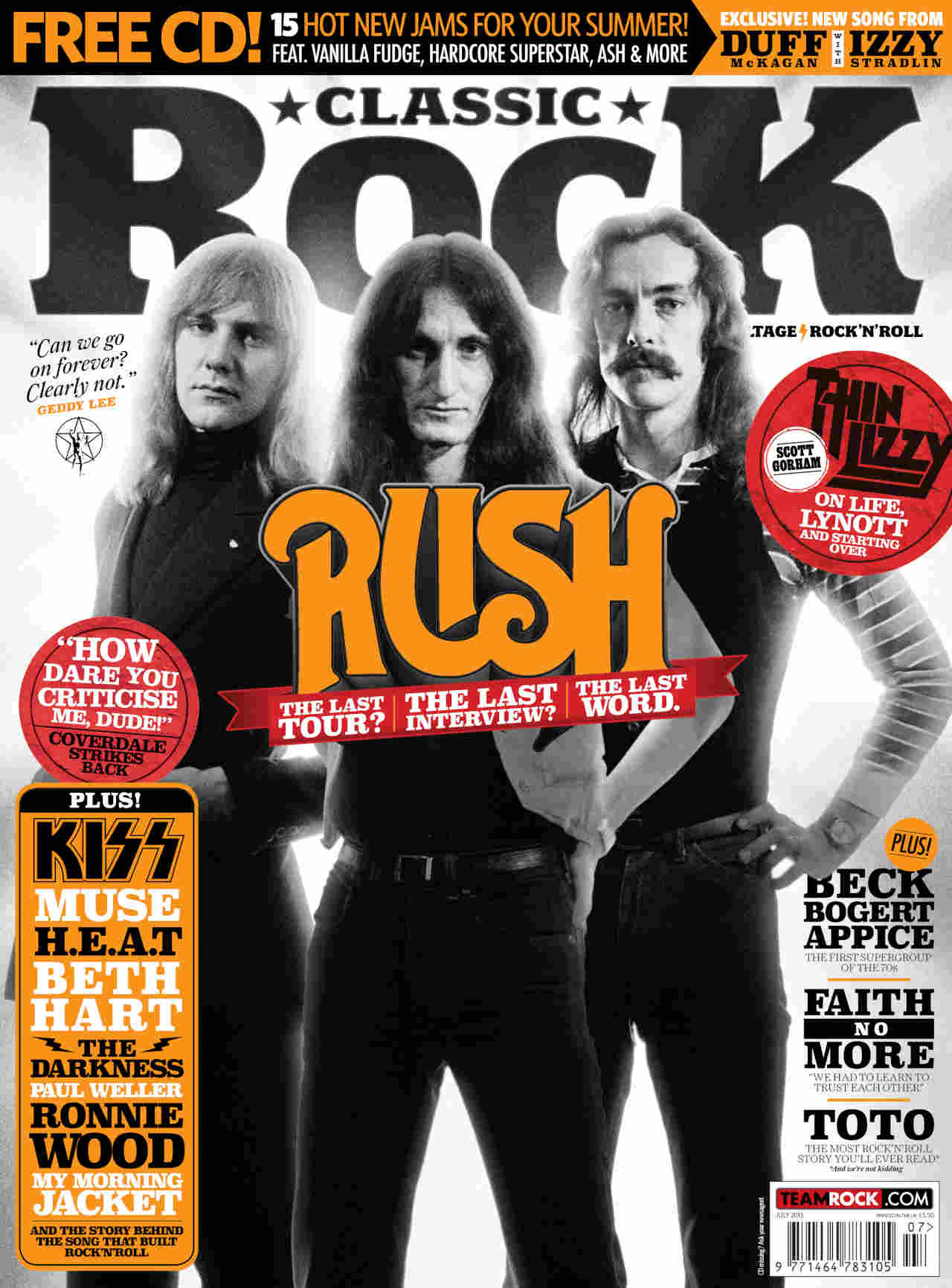

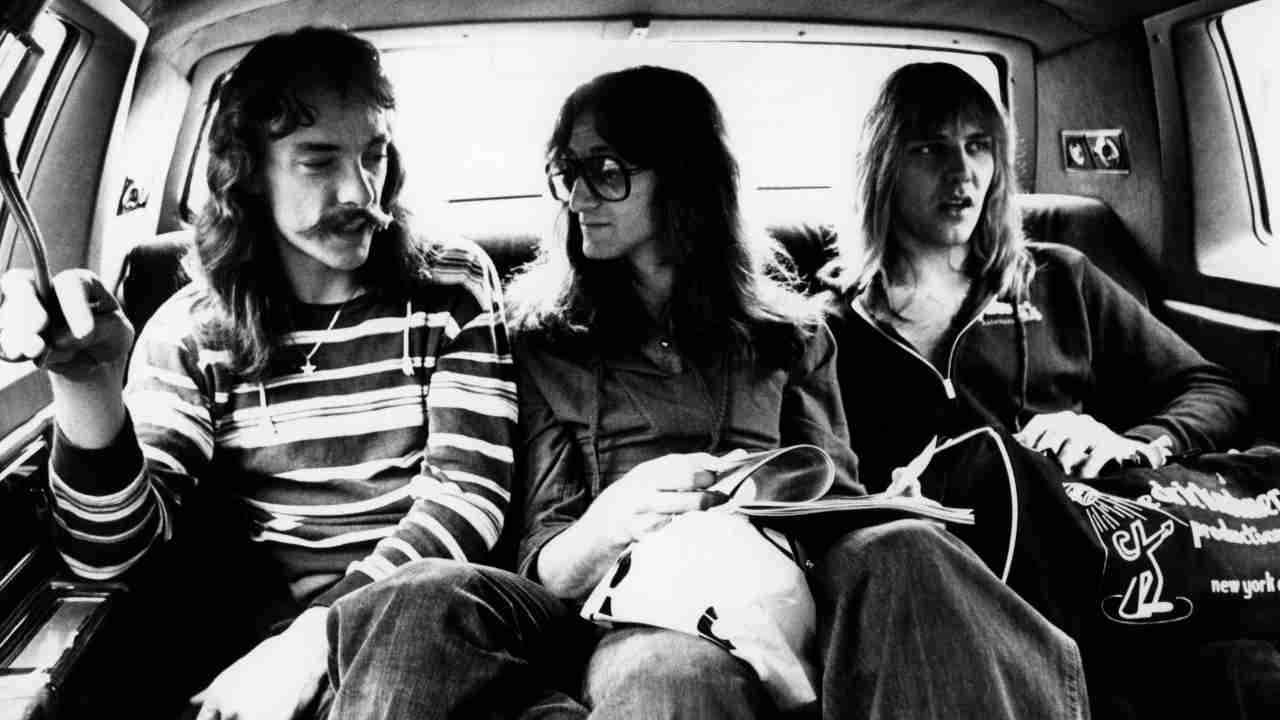

In 2015, Rush embarked on their farewell tour – just as everyone from Dave Grohl to Hollywood A-listers began proclaiming their love for the prog icons after decades as the uncoolest band on the planet. Ahead of their final bow, Classic Rock sat down with guitarist Alex Lifeson and bassist/vocalist Geddy Lee to look back on the band’s epic career.

It’s in the last couple of years that he’s noticed it happening: he’s been a famous rock star for decades, but in these past two years he’s found himself being recognised in public more frequently. Now it’s a little easier, he says, to get a table in a fancy restaurant. Even so, Alex Lifeson is not entirely sure he likes this new level of fame: “It is a little uncomfortable for me.”

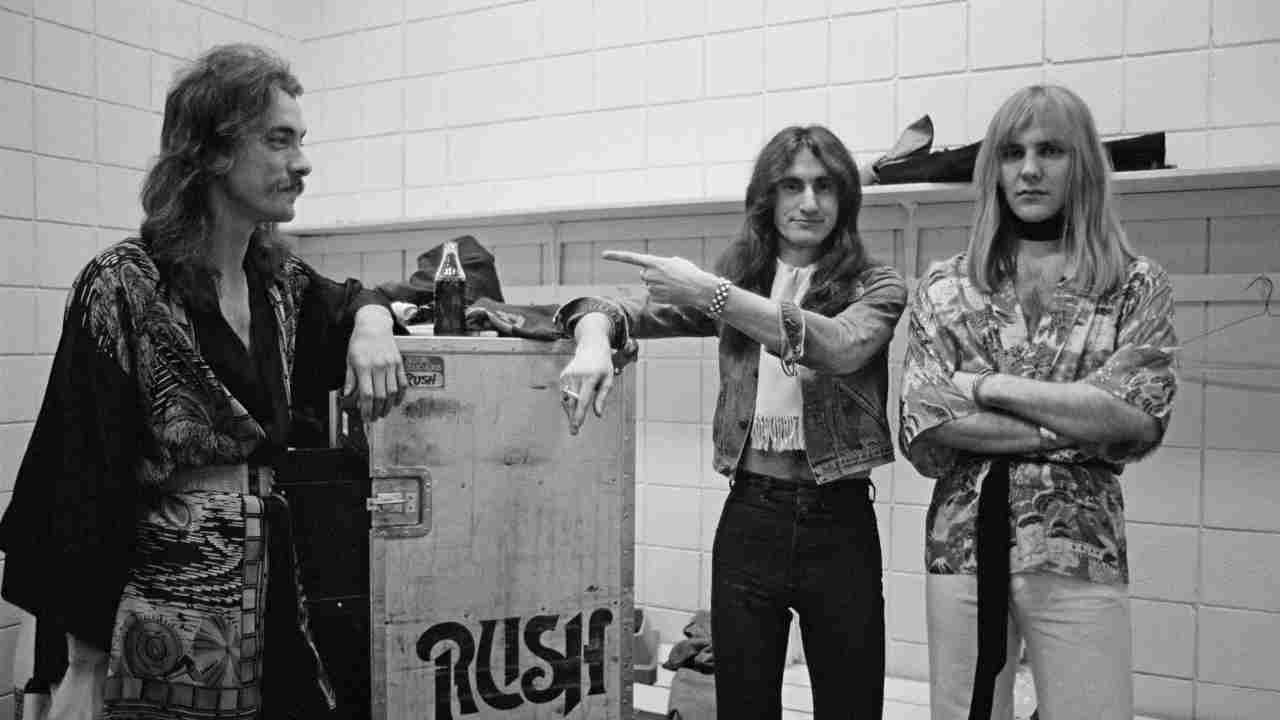

As the guitarist in Rush, Lifeson is part of one of the most successful rock bands of all time. Since their formation in Toronto in 1968 they’ve sold more than 40 million albums. And yet, for much of the band’s career, they have existed, as Lifeson puts it, “under the radar”.

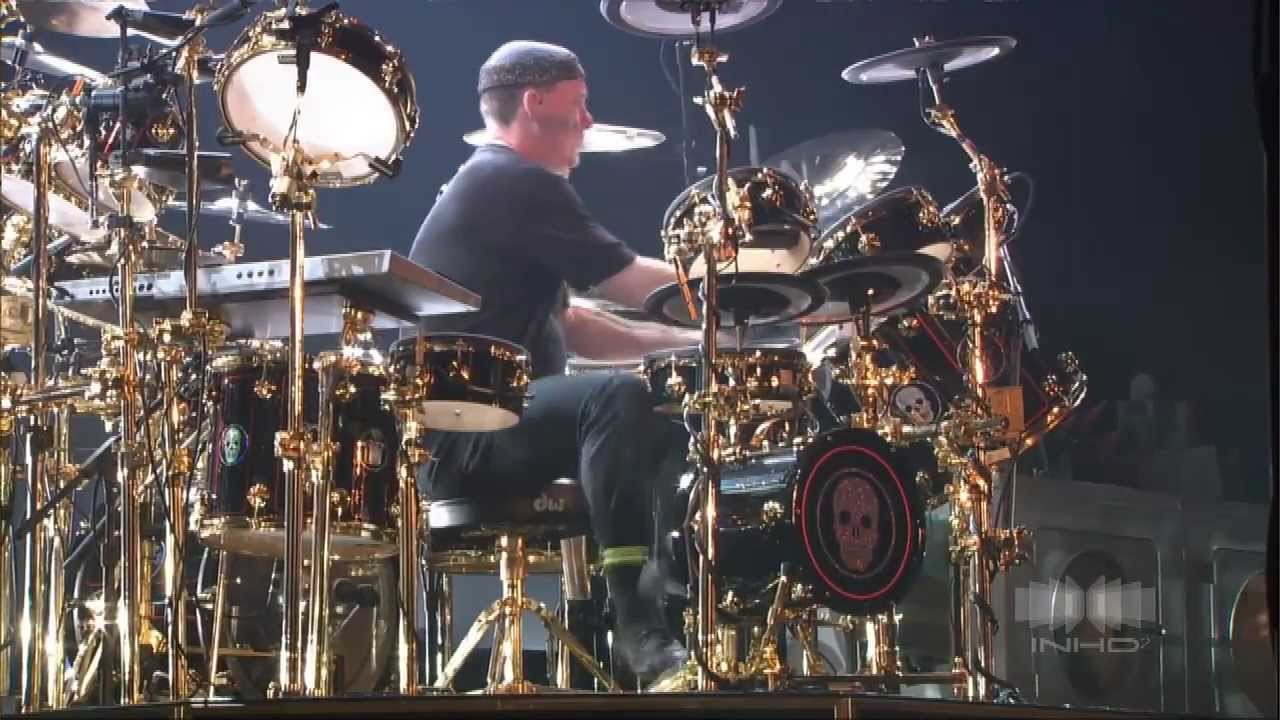

The three members of Rush – Lifeson, bassist/vocalist Geddy Lee and drummer/lyricist Neil Peart – have been playing together for 41 years now. Their brand of progressive hard rock and virtuoso musicianship – defined on breakthrough 1976 album 2112 and modernised on 1981 best-seller Moving Pictures – earned them a devoted following that has sustained them through the passing of punk rock and grunge and all that has followed. For many years, Rush have been known as The Biggest Cult Band In The World. Then the strangest thing happened: they got bigger. Rush were always a big band, but they are now bigger in a broader cultural context.

It started with the 2009 movie I Love You, Man, Lifeson says. In this “bromantic comedy” there’s a scene in which its leading characters are seen rocking out at a Rush show and embarrassing a girlfriend with their word-perfect lip-synching and air drumming: so very Rush and their fans. Then in 2010 came the band’s documentary Beyond The Lighted Stage, in which a cast of modern rock heroes such as Billy Corgan and Trent Reznor revealed themselves as Rush nerds.

And then, in 2013, came the induction of Rush into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame – at which their live performance was prefaced by the Foo Fighters playing the 2112 Overture in wigs and the kind of white satin robes that their heroes wore back in ’76. And for Alex Lifeson, that was the clincher. “The Hall Of Fame changed things,” he says. “It’s really given us a much higher profile.”

The irony in all of this is that Rush have become more famous at the very point at which their career is in the first stages of winding down. The band’s 2012 album Clockwork Angels was a huge success: No.1 in Canada, No.2 in the US, and widely acclaimed as a late-career masterpiece. This month, Rush head out on a 30-date US tour. But Peart has repeatedly stated that he is no longer willing to tour on a regular basis. He has a young daughter, and his priority is his family. He is also suffering from tendonitis. And he’s not alone in feeling the wear and tear of age; Lifeson has arthritis. He says simply: “Let’s face it, we’re coming to the end of our career together.”

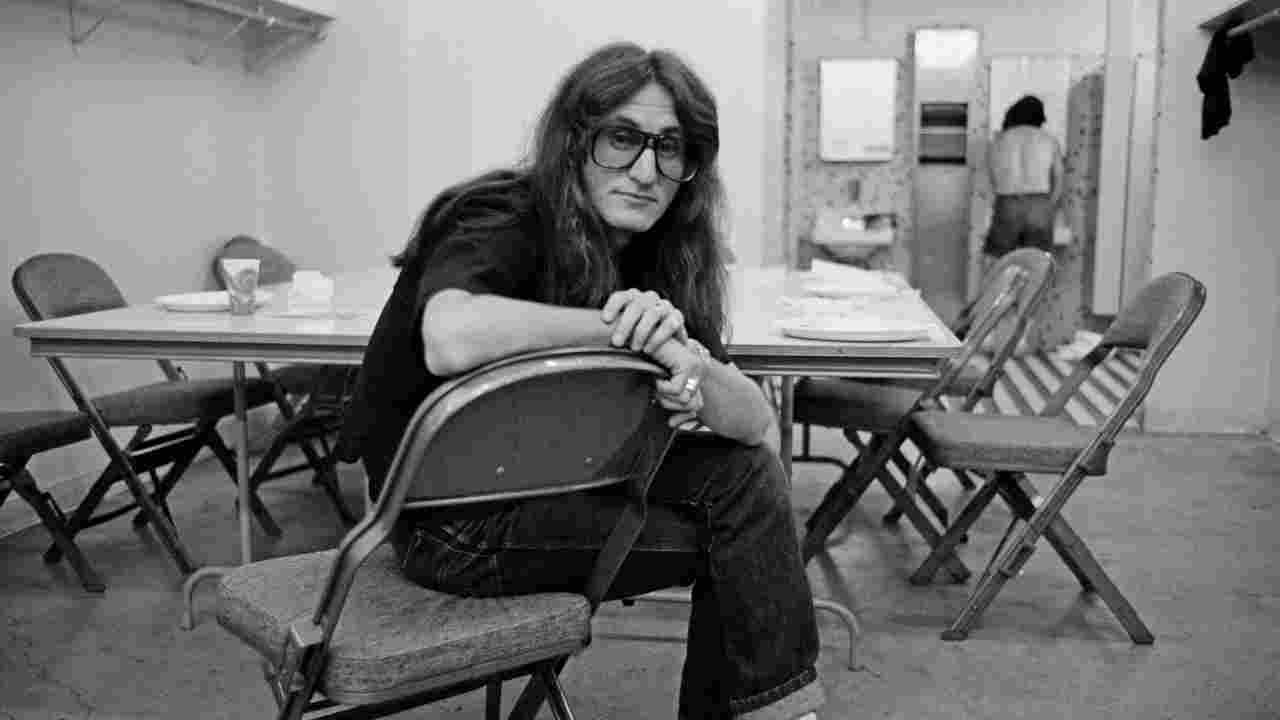

On the eve of the US tour, it’s Alex Lifeson and Geddy Lee who speak to Classic Rock about the present, the past and the future of Rush. Neil Peart is unavailable for interview. He has rarely spoken publicly in the past 20 years, and the reason for this is well documented. In the late 90s, Peart’s daughter Selena was killed in a road accident, and his first wife Jacqueline succumbed to cancer. In the aftermath, the band remained on hiatus for five years. Peart returned to Rush for the 2002 album Vapor Trails after he had remarried, but relinquished his role as the band’s chief spokesman in order to protect his privacy.

Lifeson and Lee have a small window in which to talk. After four weeks of rehearsals in Los Angeles, where Peart now lives, Lifeson and Lee are at their homes in Toronto ahead of a week of full production rehearsals back in LA.

Lifeson speaks first, and for the most part he is in typically upbeat mood. He is a frank and funny interviewee. Speaking to Classic Rock in 2014, he revealed that he had used ecstasy during the 90s, and he is similarly candid when discussing the complex dynamic within Rush in 2015. He admits that in recent months he has considered leaving the band, but when he talks about this US tour he’s buzzing. “The ticket sales went crazy from the start,” he says. “Some dates sold out in minutes. It sent a message to us that something’s going on.”

Could this tour be the last for Rush?

We’ll see. Right now the tour is what it is. Whether we add more dates, I think it all boils down to Neil, really. It’s a very athletic endeavour for him to go on tour. He’s sixty-two years old. Physically it’s difficult. And it’s the same for me.

Your arthritis – how bad is it?

I’ve had it for ten years, and this is the first time I’m really feeling it in my hands and my feet. That’s the way it goes. But it’s a lot harder for Neil. He’s got tendonitis in his arm. To be honest, I don’t know how he gets through playing the way he does, being in that sort of discomfort and pain. But he’s a very stoic guy. He never complains.

But there’s more to it than that. Neil has said many times that his first priority is his family, his young daughter.

I don’t think that’s something he even needs to talk about. I don’t know if sometimes he says these things because he doesn’t know how to come out and say it face-to-face to us that he doesn’t want to do it any more, that he’s tired of it, that he feels after forty years that’s a pretty good run and that he shouldn’t have to feel bad about not wanting to do it any more. He wants to spend more time at home and with his family. I get it. He’s never been keen about touring. It’s always a difficult thing for him.

Is Neil unhappy about doing this tour?

He was resistant to it until he started prepping and realised: hey, I can still play my drums pretty good! And then getting into rehearsals with us, there’s that whole camaraderie that he really adores. So when he’s back into the stream, he loves the swim.

Do you have similarly conflicting feelings?

The Clockwork Angels tour was pretty gruelling, as they’re all becoming more gruelling as we’re getting older. And then we had a year-and-a-half off. Having the time at home and disconnecting from being in a band, just being Al, hanging out with my grandkids, seeing my friends, all the things that people take for granted, it got me thinking: am I ready now to give it up? Can I be happy being away from it? And it really felt like I could be. Until we started to zero in on a tour. Once the machine got rolling I got swept up in it.

Where does Geddy stand on this?

Now, more than ever, Geddy wants to play. Whereas Neil probably would have quit years ago, if he didn’t feel that he owed something to us.

What do you mean by that?

I think Neil knows that we’re not ready for the end, and he doesn’t want to ruin that for us. Keep in mind: we’re like brothers. And we went through a terrible period with him inhis life and supported him and he’ll never forget that. I think he feels, as I would too, an obligation to us for having stood by him. So he’s not willing to let that go. Maybe now he is. And I get it. It’s not like, what a jerk, he doesn’t want to do this any more? I get it.

All three of you seem very reluctant to have an official farewell tour. Why?

Partly because it’s a cheesy thing to do, but also it puts you behind the eight ball if you decide that you’ve made a mistake and you want to go back on the road. We don’t feel like this is really a farewell. I’d love to make another record. It’s such a fun experience.

You feel confident there is another album in you?

Yeah, I think there is. I’m sure if we start coming up with some stuff, Neil would be right in there. He’d love that.

Going back to the very beginning, when you listen to the first Rush album what do you hear?

I hear so much promise, so much excitement. I remember those sessions vividly. I hear Led Zeppelin in it – who we adored. And I hear so much hope for the opportunity to do what we’d dreamt about doing for so many years.

When did you first feel like you’d made it?

We opened for the New York Dolls at the Victory Theater in Toronto in seventy-four. It was an old burlesque theatre, pretty run down and crappy, but to us it might as well have been Wembley.

Rush and the New York Dolls seems such a mismatch.

It was. That crowd was excited to see the New York Dolls; not so much a local heavy metal band. But it was exciting being around the Dolls. Watching them backstage it was all what you would expect. They were all drunk before they got on stage. They had girls back there. It was a whole rock’n’roll scene. We were typically Canadian and shy and stayed out of their way. I do recall after that gig I was hitch-hiking home with a friend of mine, I had my guitar with me. This couple picked me up, and we were chatting, and they said they’d been to the Dolls show at the Victory and they said yeah, they were great, but the opening act, God, they sucked. The guy’s girlfriend turned back and saw the guitar and saw me and her face just kind of froze. It was silent in the car, and I felt so crestfallen I said: “We’ll get out at the next block, please.” I got out of the car and I wanted to throw my guitar away. That was the first really bad review that we got [laughs].

Was Rush always a competitive band?

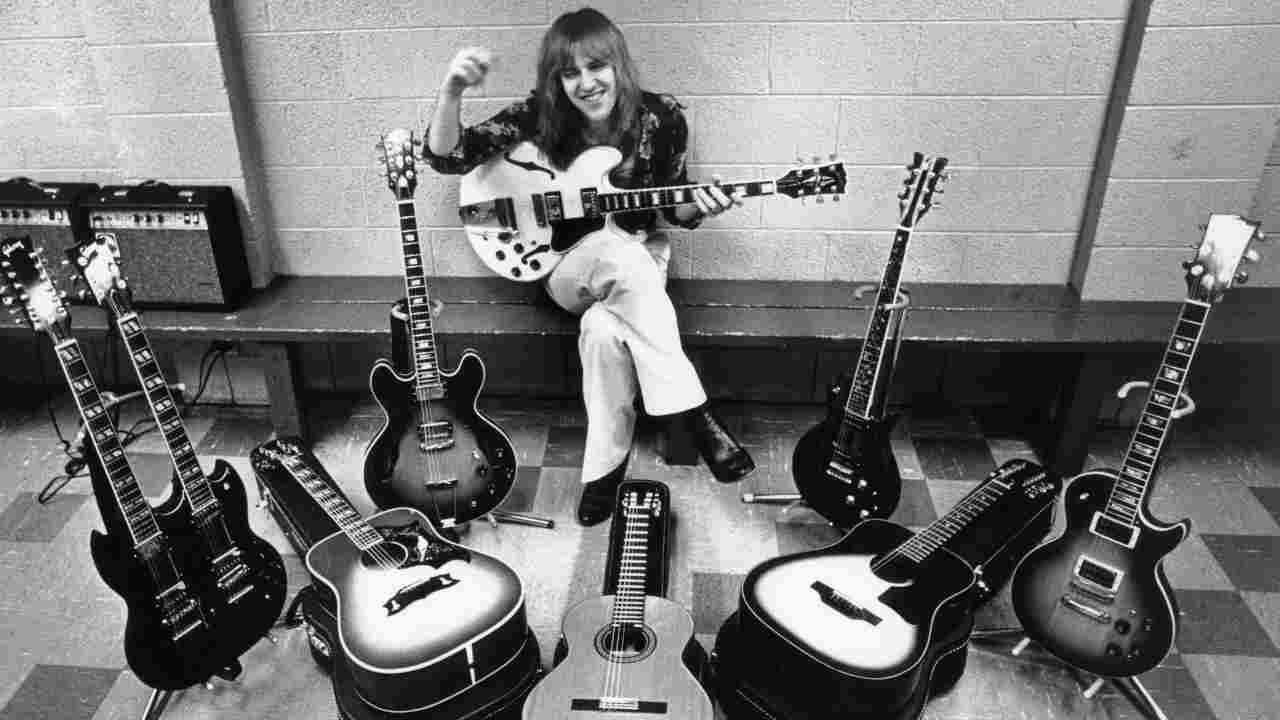

Maybe in the early days, when you were so full of piss and vinegar and so excited to play. You played with so many different bands on these two- or three-acts shows. Quite often it was competitive. You wanted to blow the other guy off the stage and be that much better. I remember we played with Heart once. This was very early, maybe 1975. It was at the Stanley Warner Theatre in Pittsburgh. There was so much talk about Heart and the Wilson sisters. We were really looking forward to meeting them. We were backstage, and Roger Fisher said to me: “We’re gonna blow you guys off the stage tonight, you just watch.” And I thought, wow, what a weird thing to say. But I think I played that much harder that night.

And Roger Fisher didn’t win that battle?

I guess, in the long run, no.

Are there Rush albums that you look back at and are embarrassed by?

Often people ask me that about Caress Of Steel. But I listened to it not too long ago and I felt proud of that record. It sounds to me like a bunch of twenty-two-year-olds trying to make a big statement. And ‘Caress Of Steel’ is such a great title.

I thought so. Around 1980 I had ‘Caress Of Steel’ written on my school bag. People laughed at me.

People laughed at us, too. You were in good company.

Are there particular songs you wish you’d never recorded?

Tai Shan was a little corny. We wanted to do something different, but maybe we had too much of a pseudo-Asian flavour to it. Maybe I should listen to it again. I don’t think I’ve listened to it since we recorded it [laughs].

A pseudo-Asian flavour like the borderline racist intro to A Passage To Bangkok?

Well, A Passage To Bangkok had a bit more of a middle-Eastern, Kashmir bent to it. Tai Shan was specifically about an experience that Neil had in China, whereas Bangkok talks about an experience we had all over the place.

You mean smoking pot?

That certainly influenced those early records. Less so as the years went on, but it was never completely out of the picture. We always made sure the tour bus was well-stocked with potato chips and cakes and things [laughs].

It sounds as if you were smoking a lot up to and including Hemispheres.

Yes, right through to Hemispheres and a little bit beyond… maybe Clockwork Angels.

Really?

Oh, sure. But Geddy gave up all of that a long time ago. He’s one of those really militant non-smokers. He leads a very clean lifestyle, although he does love his wine.

Unlike you, who got into ecstasy in the nineties. Did you tell Geddy and Neil they should try it?

I think Neil may have had one or two experiences with it, but I don’t think he liked that particular feeling.

What about cocaine?

It’s been so long now. There was a period in the late seventies and early eighties when we all sort of dabbled in that thing. But it’s such an alienating drug. I remember every time I ever did it I hated it. I loved it for that moment, and then hated everything else about it. It wasn’t good for conversation, friendship, anything.

And now you’re just a smoker?

I’m a pretty regular smoker of a very small quantity, for therapeutic purposes. I find it helps with inflammation and pain. I have my medical card for my prescription here in Canada, where medical marijuana is legal. And if we get rid of the Conservative government and get the Liberals back in, they have a whole policy about the legalisation of marijuana that is realistic and makes sense.

Might the problem with legalising marijuana be that much of Canada would slow down to the pace of the first Black Sabbath album?

Ha ha. Yeah. But is that such a bad thing?

You’ve always been characterised as the joker in Rush. How would you describe Geddy and Neil?

They’re both very funny guys, clever and smart. Geddy loves to learn about things, whether it’s baseball or wine or vintage bass guitars. He loves to get inside a particular subject. And Neil is a strange cat. He’s very bright, obviously, and thoughtful. But he’s also very private and inward, very shy. You’d be surprised at how easily embarrassed he becomes in social scenes. He can be great at a dinner party, but in a larger group he’ll be very, very, very uncomfortable, and he’ll be in a corner, nursing his Scotch, waiting to get out of there.

Was Neil always so withdrawn, even before the events of the late nineties?

In the early years he probably did more interviews than Geddy and I did. In many ways he was the band’s spokesman. Since that tragedy, he definitely did become much more private. He carries a lot of deep, deep scars from the things that have happened in his life. Most people who know what happened to him can’t even process it. But I think in general our fans do respect his privacy and know where it’s coming from. In this day and age, where nothing is private, it is a miracle that he has any privacy at all. A tragedy like that makes him more of a target.

In the late nineties, Neil said he was done with Rush. It was only in 2002 that you reunited and made the Vapor Trails album.

There’s so much emotion in that record. That took a big chunk out of our lives – that was a year of, oh, so many difficult things. Every time I listen to that record it takes me back to when we were recording it and how Neil was doing, and how poorly he was playing when he first came in the studio, and how he rose from those ashes – we all did. We were all so tentative and hurting. That album, more than any other album, has left a mark on the three of us individually.

If the band had ended in the late nineties, what would you have done with your life?

It’s so hard to speculate. I love art. Maybe I would have become a painter. Only last year I thought about taking a course at the Ontario College Of Art. It’s been fantastic to play in this band my whole life, but there is so much more out there.

Had the band ever come close to breaking up before then?

Yes. In 1989 we’d done a long tour and were mixing the live record, A Show Of Hands. We were so deeply exhausted that it just wasn’t fun any more. We wanted – all of us – to go our separate ways. It was nothing personal, just the pressure of work. Really, the stress and tension was tearing us apart. Fortunately we took a long break, and we came back renewed.

Being in this band for so long, what has it cost you on a personal level?

We were doing two hundred and fifty shows a year when my kids were young and when I should have been home with them. That’s a sacrifice that we’ve all made. But now my kids are grown up and they’re happy and content and proud of their dad. It’s worked out okay.

Looking back at your career, what are you most proud of?

I’m going to be sixty-two this year, and I’ve been playing with these same two guys longer than just about any other band in the world. That’s quite an accomplishment.

If you had to choose three albums to sum up the band’s career, which ones would they be?

2112, Moving Pictures and Clockwork Angels. I think that would cap what we’re about from beginning to end. Boy, that’s two concept records.

Well, Kirk Hammett from Metallica did call you “the high priest of conceptual metal”.

He was right! I knew he was a smart kid.

But, joking aside, when the end finally comes, how would you want Rush to be remembered?

Boy, how do you answer that without sounding kind of corny? I guess I want the legacy to be: they did it their way, and they were true to what they believed. We earned our independence from the music industry early on with 2112, and we’ve been free to do what we want. We were true to our art. I want to be remembered for that.

For Geddy Lee, being at home in Toronto for a few days between rehearsals is an opportunity to spend time with his family, and in particular his infant granddaughter. “Being grandparents is a new experience for my wife and I,” he says. “It took us a month or so to get our heads around that fact. We were sort of in denial.”

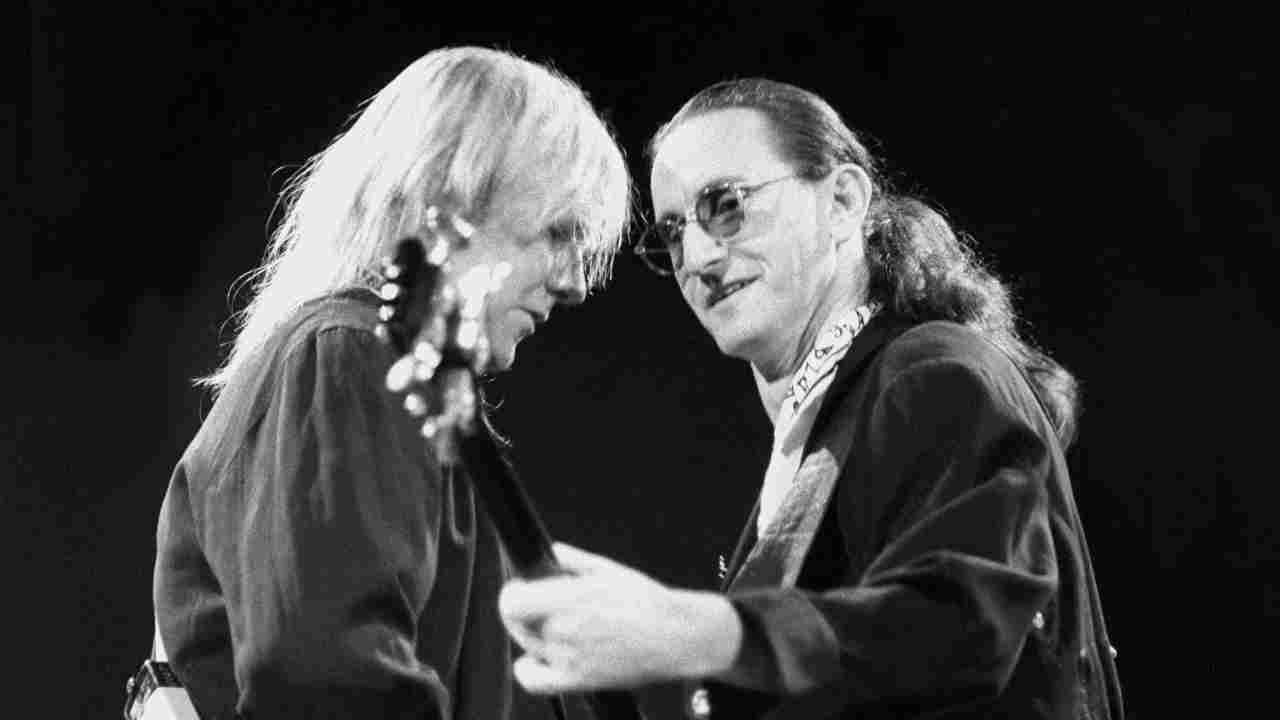

Currently, he divides his free time between Toronto and London, where he also has a home. When in Toronto, he and Lifeson are in frequent contact even when they’re not working. Around once a week, Lee says, they get together for dinner, just the two of them. Lee, a connoisseur, always chooses the wine. In the past they used to play tennis together, but not so much since Lifeson developed arthritis.

It was in Toronto that Lee and Lifeson attended school together. Peart met them for the first time in 1974, when he auditioned for Rush as they sought to replace original drummer John Rutsey. In a sense, Peart has always been the odd man out. After joining Rush, he lived in Toronto for a few years but later moved out to the country. When he relocated to Los Angeles it had little impact on his relationship with Lee and Lifeson.

“Neil was never really accessible,” Lee explains. “So the fact that he’s in California now is not a huge thing to overcome. When we need to talk, we talk.”

These days it’s Lee who is driving Rush forward. He wants to tour more. If he gets his way, the band will return to the UK and mainland Europe in 2016. Whatever happens next, he says, will be dependent on how the other two guys are feeling after the US tour: “If everyone’s really digging it, the way I think we will, then we might carry on.”

Right now, how are you feeling about the future of Rush?

I prefer to take the optimistic view. That’s my nature. But there are a lot of factors that are concerning the band at the moment. I would say that the three of us are in a different head-space about that.

Where do you stand on this?

I feel great about where the band’s at. I love playing and I don’t have any reason not to continue. Neil has a different view, due to his young daughter and what he has to put his body though in order to do a three-hour show. And Alex also has issues that he’s wrestling with. I would say it’s an ongoing conversation, about what the future will bring. Obviously there’s an elephant in the room. But the elephant is sitting politely in the corner. Sooner or later we’ll deal with that elephant head-on [laughs]. I don’t like to think of the end. I don’t see any reason for us to end until a point where we no longer can play well. But it’s clear that the concept of Rush as a massive touring band is fading.

Alex is struggling with arthritis, Neil with tendonitis. How are you holding up?

I’m fit as a fiddle. But for Alex the arthritis is not a small thing. Frankly, I’m a little surprised he talked to you about it. And really, if anything is going to mean that we can’t tour any more like we used to, it’s more than likely going to be the arthritis. Because that’s something that will directly affect his ability to play. And if I was going out on stage and I could not play the way I want to play, or the way I have played in the past, there is no way I would want to do it; I would not want to go out there and be a shadow of my former self.

This is clearly something that worries you as much as it does him.

You know, it kind of hurts me to see him when he’s having a bad day, physically. He’s one of my oldest and dearest friends. And when he’s been at rehearsal and he’s not playing his best, it’s not nice to see your friend suffer like that. This thing is in the back of his mind, and he’s afraid of it.

Neil is more vocal about his reluctance to tour.

Well, Neil has a more complicated life than Alex and I do, let’s face it. Our kids are grown up, it’s much easier for us to tour. When my kids were the age that Neil’s daughter is it was a much more difficult decision every time you walked out that door. What you also have to remember is what Neil has been through in the past. He’s been to hell and back. And now he’s got a second family that he’s trying to do the right thing by. There’s no one on earth that could blame him for that. It’s a matter of him being able to juggle what he can do with the band, and what his family can deal with, and how he feels in his heart about all that. I completely understand that.

How do you deal with such a delicate issue?

It’s an ongoing conversation; a difficult conversation, and one that we kept putting off before we got together for this tour. I think it’s hard for Neil to bring up some of this stuff, because he knows that no matter what happens he doesn’t want to feel like the guy who’s pulling the plug. It’s hard for him. And I accept that. But decisions have to be made. We have to get on with our lives. So that conversation was tough. But in the end we decided we would do a tour, and Neil was fine with that. Once he made that decision he was a hundred per cent there. There’s one thing I want to make really clear: there is no bad guy in this scenario.

If Clockwork Angels turns out to be the last Rush album, could you live with that?

Oh yeah. I’m very proud of that record. It’s certainly among our top three pieces of work.

How confident are you that you could make another?

Do I feel like we have the mojo to do more records? Absolutely. But I can’t tell you that the other guys agree. I’m not a hundred per cent sure that Neil agrees, I’m pretty sure Alex agrees.

He does. You should ask him – I did.

Ha ha. Okay. What did he say?

He said he would love to make a new album. So there you go – I’ve helped you with that one.

Thanks, Paul!

It seems that everyone loves Rush now. Is that a strange feeling?

First of all, it’s great. But yes, it is odd. The fact that more fans want to see us, and younger people are getting turned on to our music, that’s a very cool thing. It’s nice that people like us and feel okay about saying that out loud [laughs]. There’s really no negative in this whole new acceptance of us.

Do you have any idea why this has happened?

It’s hard to understand. Obviously longevity pays off. And I guess there’s an amount of passion and authenticity that we bring to our brand of music that must also mean something in this day and age.

It’s not just about the music. The documentary Beyond The Lighted Stage humanised the band.

That’s true. The documentary is what Rush is: it’s a story about three friends. By making that movie, by allowing people in, it’s shown a side of our personality that is appealing. The fact that we do get along so well, we do have a lot of fun and we love what we do, that has become kind of ‘a thing’, for lack of a better descriptor [laughs].

There are the caricatures of Rush: Alex as the joker, you the uber-nerd, Neil the professorial type.

There is certainly truth in all of that. The caricatures are a start.

And on a deep level?

I’d say that Alex is hot-blooded. If I put him in the context of Rush, he’s the raw emotion in the band. He’s the guy who’s going to freak out first, the guy who’s going to lose his temper. He’s also very sweet and lovable. He’s the guy in the band you want to hug most. He’s so funny and so considerate, but he can also be very irrational.

And Neil?

Neil is surprisingly goofy. This is the thing most people don’t realise about him. He’s this big, unwieldy guy, and when he gets in his goofy mood, it’s hilarious. The first day he pulled up for his audition, Alex and I thought he was the goofiest guy. We had no idea that lurking behind that goofiness was this professorial, serious man. We’re all more than what we appear, obviously. Or less [laughs].

You stopped doing drugs a long time ago. Those two guys did not. Are you comfortable being around them when they’re stoned?

If you hang around so long with people that love their weed, you get used to it. I’m just amazed at how good people are at functioning on that stuff.

You couldn’t handle that shit?

That’s why I stopped – because I became completely dysfunctional when I was high. I just couldn’t stop talking. I couldn’t stop pretending I was Woody Allen, or trying to take my pants off over my head. I kept trying to make people laugh, and it is easy and hard to make stoned people laugh. You’ll say something and they’ll laugh, and you’ll say something else and the room gets really quiet and it’s like, “Okay…”

Classic drug paranoia.

I was always okay when I was with the guys. What was hard for me was I’d go to my bunk on the bus and my brain would be going six hundred miles an hour. My problem is I can’t stop over-thinking everything. It doesn’t help me to have a stimulant like that. It aids my over-thinking. I prefer a glass of wine or two, that helps chill me out. That puts me in my happy place. I don’t need to be high. I feel like I’ve been blessed with a natural sort of high-ness.

So when Alex told you about trying ecstasy you didn’t feel like you were missing out?

Oh my God, I’m way beyond that. And I wouldn’t want to be a witness to it. I don’t want to be anywhere around that guy in that condition. The thought of it fills me with dread!

Are you embarrassed by any of the music that Rush have made?

Some of the early stuff makes me cringe a little. I hear a song and think: That was so Genesis-influenced. Like, what the fuck were we thinking? It’s so derivative. And the long instrumental things that we were doing back in the seventies, some of it seems so pretentious.

Long, instrumental, pretentious songs – that’s what I call ‘proper Rush’.

Okay [laughs]. I can see that. I have friends, musician guys, who say to me all the time that after Hemispheres there was nothing else of interest to them. So when you make that statement it makes total sense to me. In their minds that was proper Rush. And you saw that kind of thing in our documentary. I loved the fact that Trent Reznor got more interested in us post-keyboards, yet Tim Commerford hated anything post-keyboards. That kind of says it all.

The pretentiousness in those early songs has a lot to do with the lyrics that Neil wrote. Perhaps most pretentious of all was Xanadu, its lyrics inspired by the Coleridge poem Kubla Khan.

‘I have dined on honeydew’ [laughs]. Try singing that! Try singing about Kubla Khan, for Christ’s sake.

You pulled it off.

Oh yeah. I loved it! I was into it. But after a certain time, I guess you could say I became a little more objective about lyrics.

Were there lyrics of Neil’s that you rejected outright?

Oh yeah, absolutely. Sometimes it just doesn’t work, and I can’t get behind it.

Did that cause problems between you and him?

In the early days it was harder. We were just becoming songwriting partners, and that was a rapport and a trust that took years to develop. But he’s a remarkable songwriting partner, in the sense that he does not have the requisite ego that comes with the work.

In later years Neil has written some beautiful lyrics about the human condition, for songs such as Afterimage and The Pass. Is there a song that speaks to you more than any other on that deep level?

I like The Pass as well. It’s one of my favourite lyrics. And I find The Garden, from Clockwork Angels, one of the most beautiful things he has written.

It’s now forty-one years since the first Rush album was released. Back then, how big were you dreaming? Did you think you were going to be the new Led Zeppelin, or were you aiming a little lower – the next Budgie, perhaps?

Ha ha. Well, who dreams small? Nobody does that. Especially when you’re young, you dream big. You wanna be the next big thing. You want to be the next Deep Purple. But really, you don’t ever equate your meagre talent with your favourite bands. Especially with us being Canadians. We’re far too modest for that leap of faith.

In all the years since then, have you ever thought about leaving the band?

No. Never. I can honestly say I have not one day ever thought about quitting.

You’ve dedicated your entire adult life to this band. Any regrets?

I wish I had not been so obsessed with the band when my son was young. I wish I had been more in the moment for him. So yeah, I do have regrets about the early part of his life. But my son and I are very close now. And when my daughter came around, fourteen years after my son was born, I made myself way more available to her. You live and learn, you know?

And if the band was to end soon – for all the reasons we’ve talked about – could you accept it with a sense of gratitude for what it has given you?

I’ll be honest. I don’t like the idea of it ending. But obviously the conversations of the last year have forced me to come to terms with mortality – mortality in the sense of the band. If there is a time when we become a non-functional creative unit, then it will be hard to move on to other things, but move on I will.

August 1, 2015 is the date on which Rush conclude their US tour, at the Forum in Los Angeles. Beyond that, the band’s future remains undecided. During this tour the difficult conversations between the three band members will be continued. For now, only this much is certain: they have not yet reached the end of the road, but the end is in sight.

Geddy Lee says it is in his nature to be optimistic. Even so, he remains pragmatic. “Right now,” he says, “I’m just trying to enjoy the ride. Can we go on forever? Clearly not. We don’t know if this is the end. And if it is the end, it’s going to happen in bits and pieces. If we can’t go out and do a massive tour in the future because everyone can’t agree on that, there’s nothing to say we can’t do another record or one-off shows here and there. That’s the best way I can describe it.”

And for Alex Lifeson, there are mixed emotions. After a lifetime spent on the road, Lifeson, like Neil Peart, wishes to devote more time to his family. But he is acutely aware that if the band is going to go out on a high, it has to happen soon.

“I want to know I can play as good as I always have, or at least close to that,” he says. “I love it when people say: ‘You’ve got to see these guys, they can really play.’ That’s a legacy that I’d like to keep intact. That’s what the essence of Rush is. It’s these three guys that have always loved playing together. I know that we’re coming close to the end, but I still have so much fun playing with those two guys. When time comes, it’s going to be hard letting that go.”

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 211, May 2015