“I believed we would not get back together. I thought Rush was a place Neil was not going to be able to go back to emotionally”: how Rush survived the 1990s and early 2000s

Rush refound their rock spirit in the 1990s – only to be blindsided by personal tragedy

June 28, 2002, was one of the most emotional nights in Rush’s long and illustrious history. The band were kicking off the tour in support of their 17th studio album, Vapor Trails, at the Meadows Music Centre in Hartford, Connecticut. Vapor Trails was the Canadians’ first since 1996’s Test For Echo; this show was their first live appearance in over five years.

The build-up of emotion was intrinsically tied to the reasons for their lengthy absence. On August 10, 1997, drummer Neil Peart’s teenage daughter, Selena Taylor, had been killed in a car crash. Less than a year later, on June 20, 1998, his wife Jackie succumbed to cancer. Devastated by this double tragedy, Peart effectively quit music. “Consider me retired,” he told Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson. He underlined his point by embarking on an 14-month, 60,000-mile North American solo road trip on his BMW R1100GS motorbike.

“As the years went by, both Geddy and I thought it was unlikely that we would be working together as Rush,” admitted Alex Lifeson in 2002. “I felt that we had a terrific run, this wonderful experience that’s very unique even in the rock world, and if that’s the way it’s going to end, then I have to accept it and move on.”

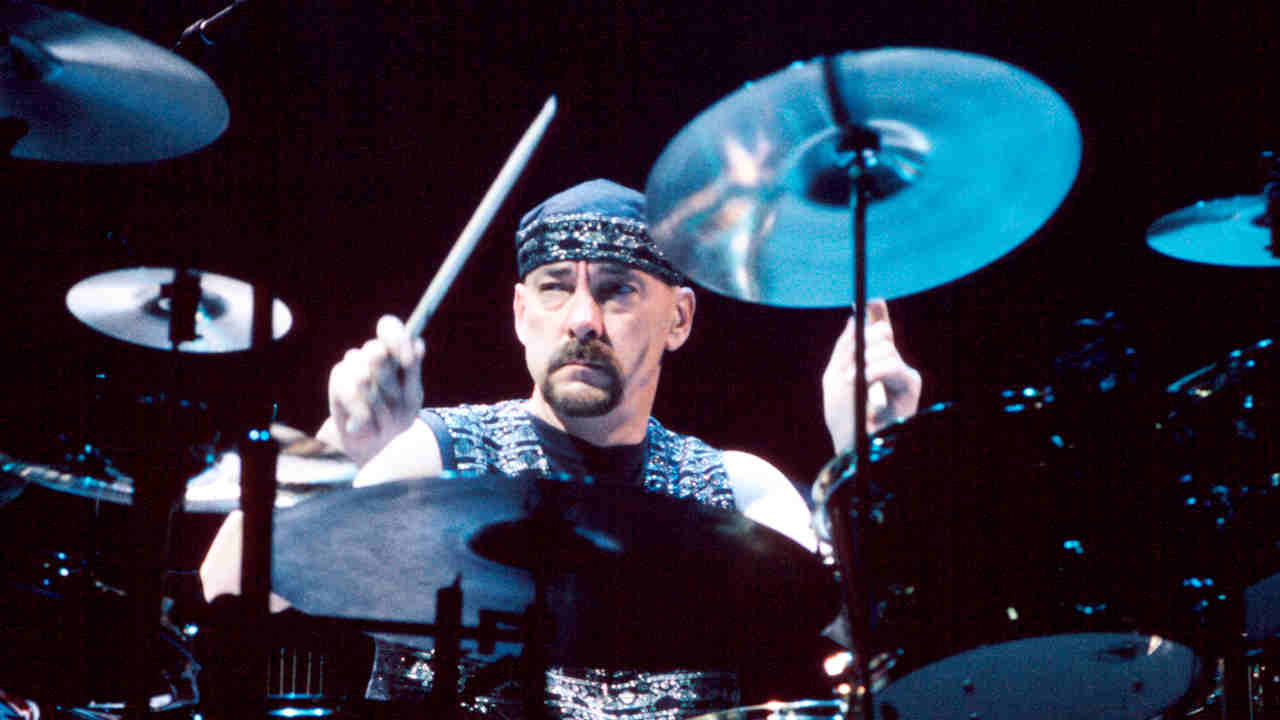

Yet here Rush were once again. Peart’s re-emergence from solitude and grief had sparked the band’s own resurrection. And it wasn’t just onstage that emotions ran high. Some members of the audience were in tears before the show had even started, while an ovation greeted the mere unveiling of Peart’s mammoth drumkit.

The 29-song setlist that night mixed up classics such as Tom Sawyer, The Spirit Of Radio, Distant Early Warning and By-Tor And The Snow Dog with more recent tracks, including several from Vapor Trails. To add to the poignancy of the occasion, their 1993 song Between Sun & Moon was dedicated to The Who bassist John Entwistle, one of Geddy Lee’s idols, who had died the previous day.

As grand finale Working Man crashed to a close, several thousand people found themselves caught up in the significance of the moment. “I remember looking out at the audience and there were people crying,” Alex Lifeson told Vinay Menon, author of Rush: An Oral History. “It was so emotional. I guess it was their chance to purge some of their emotions.”

However the audience felt, it was nothing compared to what was going through the minds of the three men up onstage. For Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson and Neil Peart, this was more than just a comeback gig – it was an act of healing. The rebirth of Rush was truly underway.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Rush hit the 1990s with renewed intent. The ‘keyboard phase’ that had alienated many of their older fans during the past decade was receding in the rear view mirror. If 1991’s Roll The Bones was hardly a return to the grandiose prog epics of old, it at least presented Rush as something approaching the power trio they were at heart.

Still, Roll The Bones hadn’t been an unalloyed triumph in the eyes of the band that made it. “[The songs] sounded much tougher live than in the studio,” Alex Lifeson told M.E.A.T magazine in 1993.

Rush’s gradual drift back to basics mirrored that of the broader music scene. The grunge movement that exploded at the start of the decade had flipped the superficial gloss of the 80s for grit and intensity. Lee, Lifeson and Peart weren’t unaware of the changes happening.

“We were loving that whole energy from Seattle and the Northwest,” Lee told Vinay Menon. “That pushed us in a different direction. That made us want to be a rock band again.”

After two albums with producer Rupert Hine, the band brought back Peter Collins to work on what would become Counterparts – ironic, given that the Englishman had been involved on 1985‘s synthesiser-heavy Power Windows and the equally slick Hold Your Fire two years later. But Rush were determined to dial the electronics right back this time irrespective of who was sitting at the studio console.

“When Alex and I started writing this record, we kind of looked at these mountains of synthesizers that were being brought into the writing room, and we kinda had this reaction; it was almost like an allergic reaction: ‘I think it’s time maybe we stepped back from this stuff,’” said Geddy Lee in 1993. “So, we went back to a more simpler, basic way of writing, which meant just guitar, bass, vocals, and drums.”

Counterparts was released on October 19, 1993. While it wasn’t a ‘grunge’ record, it was certainly a creditable modern rock record, one that acknowledged the new musical landscape without embarrassing itself trying by to pretend it was something it wasn’t. Even longtime art director Hugh Syme’s cover image - a seemingly simple diagram of a nut and bolt set in a wide blue frame – was pared down in comparison to some of the heavy duty symbolism of previous works.

The approach worked. Counterparts hit No. 2 in the US, the band’s highest-ever chart position (only Pearl Jam’s record-breaking second album, Vs, released the same week, sold more). They even notched up their very first No.1 song with Stick It Out, which reached the top spot on the Billboard Album Rock Tracks chart.

The band carried the stripped down approach of Counterparts into their 16th album, Test For Echo, released three years later. Geddy Lee had used the interim period to spend time with his newborn daughter, Alex Lifeson released a solo album, Victor, which doubled down on the more direct, rock-orientated approach of Counterparts, and Neil Peart published a book, The Masked Rider, about a bicycle trip he took around Africa in 1988, and spent a few years re-learning how to play the drums in completely different manner, taking lessons from jazz great Freddie Gruber.

For all that, Test For Echo was a relative letdown. Lyrically, it was as watertight and conceptually thought-provoking as any past Rush album. “It’s about the numbing process that happens when we are exposed to great tragedies and then we’re exposed to moments of hilarity,” said Geddy Lee of the record’s over-arching theme. “I feel that that’s the condition of contemporary man now – when we read the paper or when we watch TV, we’re not sure if we’re supposed to laugh.”

But musically, it was the sound of a band on simmer rather than bubbling away at full heat. “Test for Echo was a strange record in a sense,” Lee later told Vinay Menon. “It doesn’t really have a defined direction. I kind of felt like we were a bit burnt creatively. It was a creative low time for us.”

Still, Test For Echo was another commercial success. The accompanying tour lasted nine months, and even found the band playing the song 2112 in its entirety mid-set for the first and last time in their career. They may have dropped the pace a notch or two since the heady days of the 70s and 80s, but their path remained as steady and straight as it ever was. And then tragedy struck, and suddenly the lights went out on Rush’s future.

On the morning of August 10, 1997, just a few weeks after the Test For Echo tour ended, Neil Peart saw a police car pulling into the driveway of his house in rural Quebec. The officers were there to deliver some terrible news to the drummer and his wife, Jackie Taylor. Their 19-year-old daughter, Selena, had been killed in a single-car traffic accident while driving back to college in Toronto.

Their daughter’s death hit Peart and Jackie hard. Their friends rallied around them. “I just felt so hollow,” Alex Lifeson later recalled. “Neil’s daughter was 19 when she was killed and it just broke everybody’s heart to such an extent that nothing seemed beautiful anymore.”

The loss inevitably impacted on those in Rush’s inner circle: Alex Lifeson later said he didn’t pick up a guitar for a year. But there was more tragedy to come. In January 1998, during an extended stay in London, Jackie was diagnosed with terminal cancer. She died on June 20 that year. “I had no reason to carry on,” wrote Peart in his cathartic 2002 memoir Ghost Rider: Travels On The Healing Road. “I had no interest in life, work or the world beyond.”

He told Lee and Lifeson that he was done with Rush, and with music. Lost and grieving, he had no idea what he would do. Then he remembered something his wife had told him while she was ill: “Oh, you’ll just go travelling on your motorcycle.” So that’s what Neil Peart did.

For 14 months, he rode the length and breadth of North and Central America on his BMW motorbike, from chilly Alaska to blazing Mexico, “lost in my own sorrows.” He travelled alone, stopping off at diners and gas stations, observing the people he encountered yet largely unrecognised by them. Music – his own and other people’s – was the last thing on his mind.

He met up with his bandmates occasionally, though mostly he stayed in touch via postcard. Lee and Lifeson knew him well enough to give him space. Neither had any expectations that Rush would reconvene. “The longer it went, the more I believed that we would not get back together,” Lee told the Mercury News in 2002. “I just thought it was a place that he was not going to be able to go back to emotionally. Neil obviously was not quite the man he used to be.’’

It was Rush’s longtime photographer, Andrew MacNaughton, who played a key role in nudging Peart back onto the road to happiness and, ultimately, reuniting Rush

“Andrew was determined to find a ‘match’ for this crusty old widower,” wrote Peart on his blog in 2012, shortly after MacNaughton’s death at the age of 47. The photographer sent the drummer Polaroids of a photo assistant he had been working with named Carrie Nuttall. “I was reluctant, gruffly telling him, ‘Not interested.’” recalled Peart.

But something about the “pretty, dark-haired girl” hooked Peart’s attention. When he next visited Los Angeles on his motorbike, MacNaughton arranged a double date so the pair could meet. They hit it off. By the end of 1999, Peart and Nuttall had embarked on a relationship. Within a year, they were married.

Lee and Lifeson were elated that their friend had found happiness once more. “He fell in love and saw that there was beauty in the world,” Lifeson told The Costa Times. “He started to rebuild his life based on that.”

It was Nuttall, too, who steered Peart back towards music. “She didn’t know anything about the band,” Lifeson told Rush: An Oral History author Vinay Menon. “But one day she said to Neil, ‘It’s my understanding that you are a really good drummer and you had this long career and you’re about to throw that away at a time when you need that more than anything.”

Something shifted in Peart. He contacted his bandmates. As Alex Lifeson put it: “He came to us and said, ‘I’d like to try it. I don’t know if I can do it, but I’d like to try.’”

Work began in January 2001 on the album that even Rush themselves weren’t sure would ever happen. Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson hadn’t been idle during the latter part of their band’s enforced absence. The pair contributed a rock version of Canadian national anthem O Canada to the 1999 movie South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut, while Lee released a solo album, 2000‘s My Favourite Headache, and Lifeson composed music for TV ads and collaborated with hard rockers 3 Doors Down on three tracks from their second album, Away From The Sun.

But this reunion was something else entirely. Not only was it freighted with heavy emotion, but the three men at the centre of it had to recalibrate their relationship as musician after so many years of not playing together.

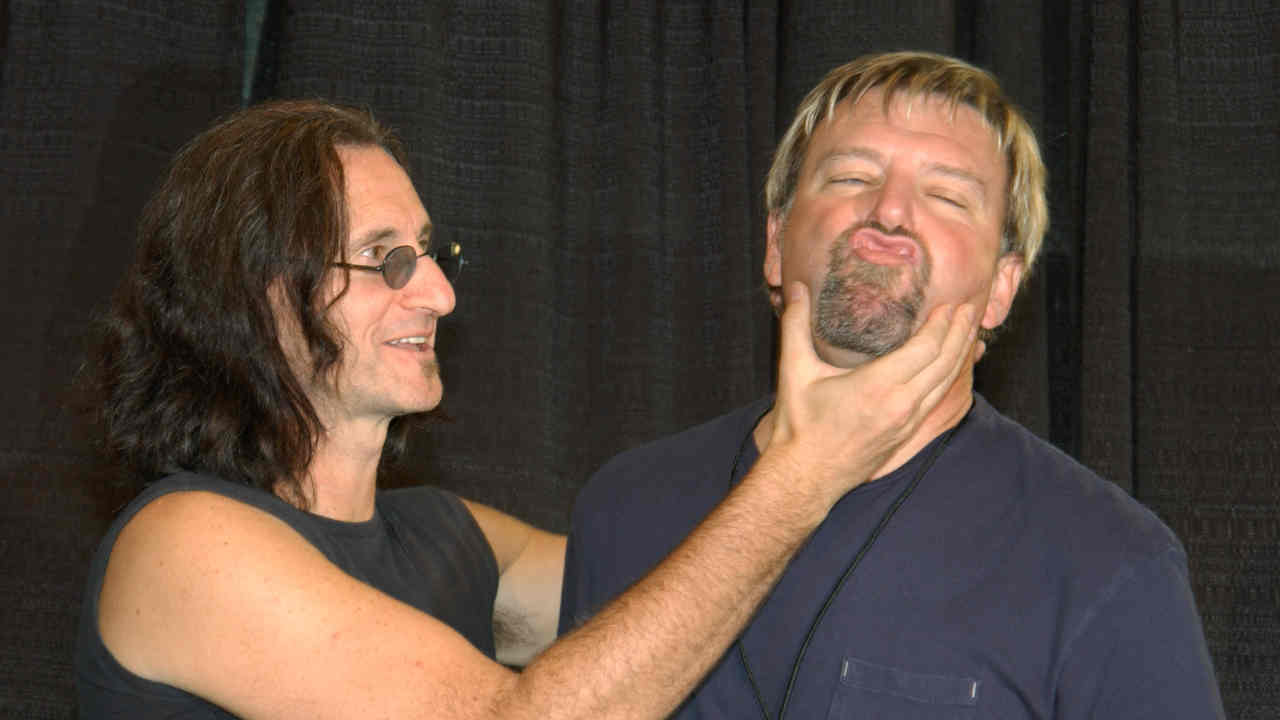

“It was a very delicate beginning for all of us,” Lifeson told The Costa Times in 2002. “We kind of needed to find our place, our positions. The first couple of weeks we spent really just talking, hanging out and getting to know each other again. But once we did, it settled in, in a way that was far beyond anything that we’d done in the past.”

Still, Rush resisted the urge to plunge headlong into the creative process, preferring tentative steps. The seeds of the songs emerged from Lee and Lifeson jams, which they passed on to Peart to work out his drum parts. It was time consuming and laborious, but then it had to be.

“The first two months I don’t think we wrote anything that we were really crazy about,” said Lifeson. “We took a break for a week, then came back in and had sudden clarity. We knew what was working and what wasn’t. From that moment on, things started to come together. The record really took on a life of its own at that point.”

The writing and recording process took 14 months – significantly longer than any previous Rush album. This was a decision made out of both choice and necessity. “It required patience,” said Lee. “I felt that I didn’t want to come back after all that and put out something that wasn’t as strong as it could possibly be. I thought it was time for us to be as intimate as we could be with our music, just go with our guts.’’

Despite the lengthy gap, Vapor Trails continued the musical trajectory that began with Counterparts and Test For Echo. Where those albums pared back the keyboards that had defined Rush‘s sound during the 80s, this time they dispensed with them completely.

“Leaving the keyboards off this record was very important to me, and Geddy was open to that because he knew that I’d often worried about their presence in the band,” said Alex Lifeson, who had felt notably sidelined at points during the late 1980s.

Vapor Trails was released on May 14, 2002. Taken as a whole, it was a good Rush album but not a truly great one, partly let down by an uncharacteristically flat mix from the band and co-producer Paul Northfield. Still, One Little Victory, Earthshine and the moving Ghost Rider sat comfortably in the top tier of late-period Rush songs, the latter finding Peart detailing his literal and emotional journey in the wake of the tragedies of the previous decade.

Yet, it was easily the most significant album Rush had made since 2112 – if only because that brought these friends back together as a unit, healing their pain through music. Tellingly, at 13 tracks and 67 minutes, Vapor Trails was their longest album to date. It was as if a dam had burst and all the emotion and music that had built up over the past few years had been released.

That the album opened with a brief but instantly recognisable Neil Peart drum barrage wasn’t accidental. This was notice, as if anyone needed it, that The Professor was back where he belonged. And with him, so were Rush.

The Vapor Trails tour which began with that night of high emotion in Hartford, Connecticut lasted five months - moderate by previous epic standards, but wholly understandable given the circumstances leading up to it. It concluded with three huge shows in South America – the first time Rush had visited the continent. Equally notably, it featured a trio of industrial-sized Maytag washing machines onstage behind the band, which a roadie periodically fed with Canadian dollars.

The washing machines were more than just an amusing and surreal stage prop. They showed that the events of recent years hadn’t dented Rush’s sense of humour or joy in the music they made.

That joy was never more evident than in their next project, 2004’s Feedback covers EP. This was Rush saluting the legends who had inspired them when they were starting out all those years ago: The Who, Cream, The Yardbirds, Buffalo Springfield, Love.

“It was short and sweet and it came up quickly,” Geddy Lee told Classic Rock. “We’ve always talked about throwing cover songs into our shows for fun, but we’ve never really followed through on it. Then a friend of mine suggested that if we weren’t going to do a [proper, all-new studio] album then maybe this was a good way we could pay tribute to our past.”

After the trials of the late 90s and the careful labours involved in making Vapor Trails, Feedback felt like a sigh of relief. The darkest period in Rush’s career was over. Now it was time to turn the page and begin the final chapter.

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.