Ronnie Wood: cleaning up, beating cancer, and what's going on with the Stones

After early days as a signwriter, Ronnie Wood joined the Jeff Beck Group, the Faces and the Stones. More recently he's beaten cancer, recorded a Chuck Berry tribute and fathered twins

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

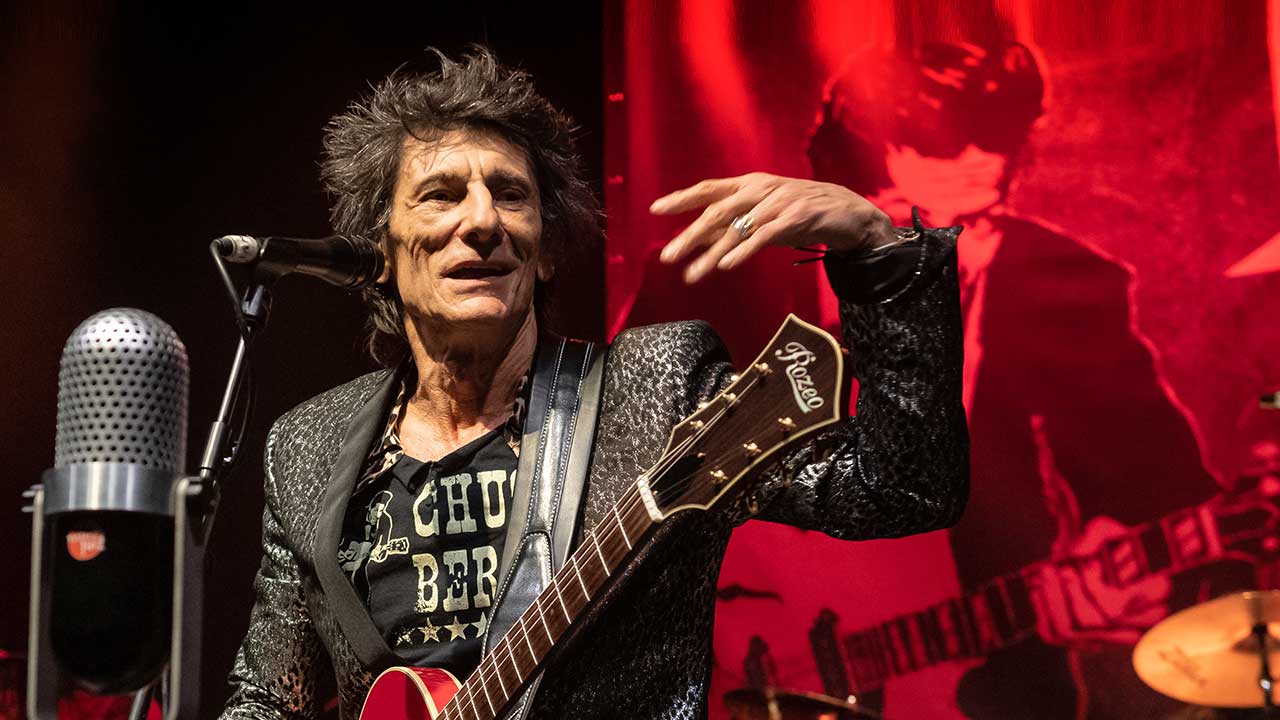

Honest Ron – Rolling Stone, ace Face, patron saint of smokers, artist, broadcaster, Jack the lad, all-round diamond geezer – bounces into the Presidential Suite of the hotel like a bright-eyed endless party in skintight black strides. Ebony thatch tilted skyward, open black shirt over Chuck Berry T-shirt, bright red sweater draped over his shoulders, Ronnie Wood, addiction-free, cancer-free, is as close to the living, breathing embodiment of rock’n’roll as one might expect.

He did it all so you wouldn’t have to.

What’s the strongest memory you have of your childhood? Up in my bedroom with my Dansette player, learning Chuck Berry licks.

Article continues belowWhere did you get your first guitar?

During my colourful childhood my brothers, Art and Ted, got me my first guitar. It was lent from a guy called Davey Hayes. But when he got called up for the army he said: “I’ve got to take my guitar with me.”

So I only had a guitar for a few months before it was taken away. I was only about seven, and it was really heart-rending to have to do without a guitar. So my brothers saved up the deposit and got me one on hire-purchase. That was the first one I owned, which I swapped-up for my Rogers guitar when I was doing my sign-writing job.

You seem to have always put yourself in the way of opportunity, and never just stood back and waited for good luck to happen. Were you always naturally confident?

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Yeah, I suppose I was, in a very humble way. I’d always go in through the back door, always make sure I was in the right place at the right time, I’d feel the situation.

You’re often asked if it was a difficult decision to choose between art and music, but I get the impression you never did.

I tried to make my money as an artist when I was young, tried to get into scenic design at the film studios, but it was a closed shop, you had to be a member of a union. There was a lot of red tape to get through for commercial art jobs.

And the interviews?

I don’t know how anybody ended up getting a job in the graphic field I was trying for. That’s why I took the sign-writing route, a looser way in but still some form of draughtsmanship. I’d develop my freestyle of painting, while getting my letter shapes dead right.

But the struggle I had with art was eclipsed by my musical freedom within my garage band, rehearsing in the garage with my mates. We’d get a fiver a gig, and before you know it I could make five quid a week and give my mum two-pound-ten, which was unbelievable. I was the main breadwinner in my family in my teens.

You immediately recognised the Stones as being your people.

When I first saw them I said: “I’m going to be in that band.” I never doubted it, and that was it. I reckon if you have a big enough belief in something, it’ll happen. It was the same with my art. People would say you’ve got to be up to such a high standard, you’ll never make it. I was like: “Yes I can. I can be an impressionist, a draughtsman, I can be whatever I want.”

Obviously the Jeff Beck Group were a fearsome unit, but you were on bass. Although it was Jeff who ultimately split the band, were you getting a bit itchy to move on yourself by then?

Yeah, because The Birds, The Creation and the Jeff Beck Group were my stepping stones towards the Stones, and then the Small Faces split up right before my eyes, which wasn’t long after the split-up of the Beck Group. [JBG drummer] Tony Newman put the cat among the pigeons, saying: “Unless we get more money we’re going on strike.”

Suddenly Jeff’s not there. We weren’t really surprised. We were used to him not turning up for the odd show. But when he went back to England, we thought: “Oh.”

There’s been a lot of speculation since that had the Beck Group played Woodstock (which they turned down), been in the film and reached a wider audience, they wouldn’t have left the vacuum later filled by Led Zeppelin, and would have gone on to attain the enormity latterly enjoyed by Zeppelin. But could you have stood being the bass player in the Jeff Beck Group for the rest of eternity?

Would we have been more famous if we’d played Woodstock? We’d have certainly carved our notch in history for being part of Woodstock, but I think as fate had it, it was what was meant to be. We were very disappointed, because we knew Woodstock was looming, but at the time it was just a rumour that it was going to be that big. Festivals were still quite a new thing. We did a few gigs with Hendrix that were open-air. He was always good to me. He’d always say to Jeff: “Let the bass player have a solo.”

A big part of the Faces’ appeal was that from the outside you looked like a tight-knit gang that everybody wanted to join, a band of brothers. What went wrong?

We were a band of brothers, and we did love going on the road. Didn’t like the recording studio much. Everybody was jangling their keys as soon as they walked in, and that was our downfall. We should have spent more time on the creative side. I learned that from the Stones. That’s how they’ve maintained their high standard, all the time spent songwriting and in the studio.

As a live rabble the Faces had great camaraderie between us, but we knew it wasn’t going on forever because the management structure favoured Rod’s solo career. Which we can’t blame him for. Rod was always very good to me, taking me with him, giving me the freedom to play the guitars and bass on his solo albums.

I had the best of both worlds there. I was enjoying being in the Faces and on the creative side of Rod’s solo albums. But I knew it couldn’t last forever. Tetsu [Yamauchi] was a real wild card after Ronnie Lane left the band, too crazy, and I was bumping into the Stones more and more often.

Was there anything you heard from Mick Jagger or Charlie Watts in Mike Figgis’s Somebody Up There Likes Me documentary that surprised you?

It was nice to hear Charlie say that Mick never gave up on me. I thought: “That’s lovely”, and it made me look back, and Mick has supported me through lots of times when I was trying to straighten up. He was very supportive of my rehab stuff.

Admitting you’re an addict is one thing, but cleaning up?

It’s a very individual thing. It’s a realisation that: “Oh God, this is going to kill me if I carry on.” It’s basically common sense. Some people didn’t have that cut-off valve, and they just carried on until their body shut down. I wanted to stop before my body shut down. It was purely a selfish decision to save my life. I cleaned up merely to stay alive [laughs].

Is life within the Stones’ bubble akin to living a life in suspended animation, where no one need ever get old?

My brain stopped telling me : “You’re getting older” around thirty. I remember my fortieth birthday, my fiftieth, milestones, but even then I was like: “I’m not forty”… Seventy-two? Forget about it!

Your lung cancer diagnosis must have turned your world upside down; you’d only just become a father again, to your twins. The outcome was ultimately positive but it must have been a terrifying period.

Yeah, in the few days of not knowing, I thought: “Oh dear. Well, I’ve had a good innings.” When I got the news it could be removed and that there’s no cancer in the rest of my body, I was like: “Somebody up there likes me even more!”

After all the years I smoked so heavily, to just get off with cancer in the left lung that they were able to remove was just fantastic, a blessing.

You’ve given up the fags now, but quitting any addiction is especially hard if you don’t find new challenges to fill the void.

Yeah, I’ve got twin headaches now. I need eyes in the back of my head looking after Alice and Gracie. They’re three and a half, which shows you just how quickly time flies. So apart from the renewed vigour and zest for life the kids give me, the music and the art are still blossoming and spiralling up.

As a new challenge I’ve been revisiting childhood influences like Chuck Berry. Playing it live. I’ve found Ben Waters, who’s like Chuck’s piano player Johnnie Johnson. It’s so great to play with him, because he just inspires me.

Will we ever see another Faces live performance?

Me, Kenney [Jones] and Rod just did a show at Wentworth for Prostate Cancer, and we got on so well. Everyone loved it, and the vibe afterwards… Rod was blown away, Kenney was lovely. I know we’ll do some more, yeah.

Watching the Stones most recent live performances I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say the band are playing better than ever.

We are better than ever.

Today’s Stones seem to be making every performance count. After Mick’s heart scare and your cancer scare, it’s maybe as if everybody involved is beginning to see the Stones as a finite entity; not simply carrying on as if it’s an endless party, but treating every performance as something to be truly appreciated.

Yeah. It’s brilliant. There’s a great feeling within the band and with the crowd nowadays, I think we’ve definitely got the bug again, we just wanna keep touring. “Let’s go and do some more gigs.” Even Charlie, who was always like: “I don’t know if I wanna go on the road any more.” He’s like: “I’m up for it, whenever you want, let’s go.” Which is great.

And you can absolutely see it in the performances. Keith’s firing on all cylinders as well.

That’s what he does.

There was a point in time where there’d be occasional stumbles, but now you can see he’s fully on top of his game, back to being the best Keith he can possibly be.

That’s it, another step up to the bar. I’m playing the best I’ve ever played, for some magic reason, and I love it, and I think we’re all raising the bar every time we play now.

Not that we didn’t before, but now we’re, like you say, more conscious of… surviving, how lucky we are. With my recent scare and Mick’s scare, Charlie not so long ago, Keith not so long ago, there was a lot of shit going down.

Watching Mick’s first gig after heart surgery, he wasn’t exactly taking it easy.

In the hospital they said they’d never done that kind of surgery on a seventy-five-year old. There’s no precedent. And nobody goes back to the office when they’re that old, they normally just go back to gardening. They don’t go back to running ten miles around a stage.

The Rolling Stones is a very healthy place to be these days. Not only is the level of fitness high due to all of your bounding about the stage, but every time you go tour you need to pass medicals.

Which are getting harder and harder to pass now [laughs]. Poor Joyce [Smyth], our manager, is like “Oh, no! More insurance for the next tour”.

You’re very fortunate to have that safety net, because things could have been missed in the normal run of things, so it must be reassuring to be able to go for the full MOT every year or so?

Yeah, it is. And without these MOTs a lot of these things wouldn’t have been found. We would have been carrying on merrily while ploughing into a wall, basically.

Where are we as regards a new Stones album?

That’s ongoing. We are very happy with the way studio work’s coming on, but, as you know, the Stones never make an album overnight. But aside from our busy schedule touring, we’re just fitting little studio visits in and it’s shaping up nicely.

It won’t be another [Stones’ 2016 covers album] Blue & Lonesome?

Oh no, a proper new studio album.

Of course, [title track of the 1973 Faces album] Ooh La La tells us that a man has to make his own mistakes. But if you could go back, what advice would you give your younger self?

I’d say [sings] ‘Please don’t ever change a thing’. Life’s full of curves and swerves, and ups and downs. You just have to go with it. Follow your heart.

Looking back, I suppose your darkest time would have been on the pipe, free-basing cocaine.

Yeah. It’s a terrible millstone around your neck because it just grabs you and it’s a hard one to kick.

Harder than the fags?

Good old Champix, little tablets that cut off the part of the brain that craves cigarettes. One day you wake up and go: “I’m not doing that any more.”

And that’s it. It’s like I never smoked. When I see somebody smoking I think: “Are you sure?”

Ronnie Wood's Mad Lad: A Live Tribute to Chuck Berry is out now. The next leg of The Rolling Stones' No Filter North American tour kicks off in San Diego on May 8.

Classic Rock’s Reviews Editor for the last 20 years, Ian stapled his first fanzine in 1977. Since misspending his youth by way of ‘research’ his work has also appeared in such publications as Metal Hammer, Prog, NME, Uncut, Kerrang!, VOX, The Face, The Guardian, Total Guitar, Guitarist, Electronic Sound, Record Collector and across the internet. Permanently buried under mountains of recorded media, ears ringing from a lifetime of gigs, he enjoys nothing more than recreationally throttling a guitar and following a baptism of punk fire has played in bands for 45 years, releasing recordings via Esoteric Antenna and Cleopatra Records.