Rebel Sons: 80s British Prog Revival

Johnny Sharp, aka NME's Johnny Cigarettes, looks at what exactly happened during the heady 80s, and more importantly, why it happened...

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

This wasn’t supposed to happen. According to the official, BBC approved version of rock history (you know the one, featuring footage of Rick Wakeman in a wizard’s outfit and the Emerson Lake & Palmer trucks rolling down the motorway), progressive rock was consigned to the dustbin of musical history approximately five minutes after the Sex Pistols swore on live telly. Anyone who was remotely cool immediately binned every prog album they owned, cut their hair and got with the programme. Year Zero had arrived, and nothing that went before could ever dare to show its face again in polite society.

Nonsense, of course, but all the same, by the turn of the 1980s, there had unquestionably been a seismic shift in the UK musical landscape. All of which meant, ironically, that what had been dismissed a few years previously as the bland, complacent music of the establishment was now the ultimate outsider music. In the early 1980s, if you wanted to be a true rebel, you came out of the closet as a prog fan.

Yet if you wanted a platform for your illicit form of self-expression, you had your work cut out. “Trying to get gigs in those days was terrible,” recalls Mike Holmes, who spent the early 1980s trying to make a go of things as guitarist and co-songwriter of IQ in and around Southampton. “So many times we played to, literally, two people.”

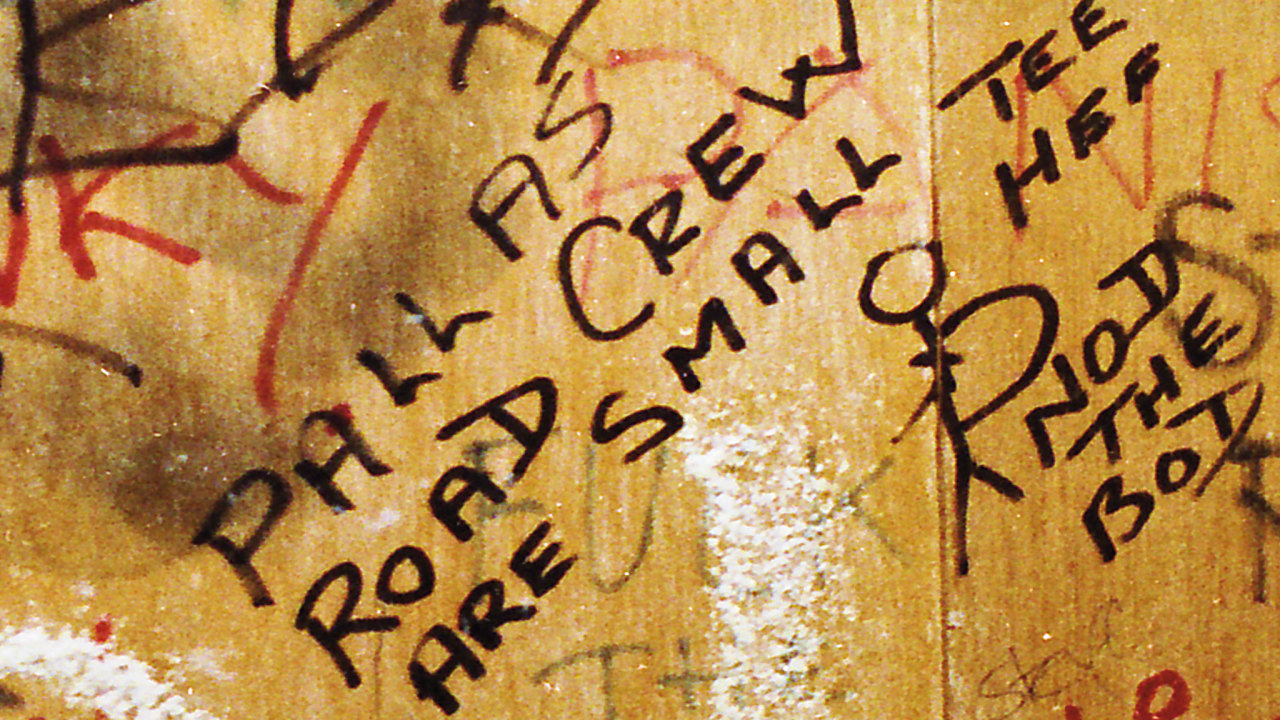

Article continues belowUp in Scotland, however, things were looking more promising. Far removed from the fashion fundamentalism that has always pervaded the London music scene, Aberdeen-based proggers Pallas were pulling in substantial crowds from the silent majority that had not, contrary to folklore, obediently retuned their ears to the new orthodoxy overnight. A live cassette album, 1981’s Arrive Alive, further spread their reputation.

Meanwhile, hundreds of miles south, Buckinghamshire-based Silmarillion had culled the Tolkien-derived first syllable of their name to become Marillion, and taken on board a compatriot of the Pallas boys, calling himself Fish, as their lead singer. Before long, the two bands found each other.

“Once we got a following up here, we’d invite Marillion to support us in Scotland and we’d support them down south,” recalls Murray. “We thought we were just a lone voice in the dark, but soon we found out there were bands like us coming out of the woodwork everywhere – it was like pop-up prog!”

In many ways, it shouldn’t be surprising that a new generation of prog bands should have come to prominence in the early 80s. It fits in with the usual decade-long cycle that sees those people who are fans at 13 or 14 soon pick up instruments and form bands of their own, and by the time they’re in their early 20s, they’re writing their own music informed by those teenage influences.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The difference in the neo-proggers’ case was that they found their youthful passions were now considered somehow taboo. That’s probably why there was a distinct bloody-mindedness about that scene. As Mike Holmes puts it, “Our attitude was: ‘Yeah, we know it’s not cool, but sod you, we like this kind of music and we’re going to play it.’”

They soon found that there were plenty of people who wanted to hear it. What the scene now needed was a spiritual home. They found it in the shape of the legendary Marquee club on London’s Wardour Street.

“The Marquee had a great attitude,” remembers Holmes. “They were really open to new bands and up for giving people a try. We’d hang around the venue and badger the venue manager, Nigel, for support slots. Then one day he said, ‘OK, you can do it tonight,’ and that was the first of many times we played there.”

This was our own version of Anarchy In The UK. If punk was trying to shock people and cause a reaction against the establishment, this was a reaction against the reaction - Graeme Murray, Pallas.

The scene was competitive, but also mutually supportive. And although from early on Marillion led the way in terms of following and record label interest, their popularity was turned to the advantage of their contemporaries.

“Marillion were doing well,” recalls Holmes, “but the people who went to see them would also be looking around to find other stuff that was similar. Even when we weren’t playing with them, we’d hang out outside their gigs, giving out flyers and selling demos.”

Other bands, such as Reading’s Twelfth Night, Gloucestershire’s Pendragon and Solstice from Milton Keynes, joined this new secret society, dedicated to the love that still dared not speak its name in cooler circles. And the new movement was also catching the attention of a few sympathetically disposed journalists from magazines such as Sounds and the newly launched Kerrang! “Bands were being written about, record labels were getting interested and you could tell there was something happening,” says Murray.

Marillion were signed to EMI in 1982 and after singles like Garden Party and He Knows You Know, gatecrashed the charts the following year. It exposed the new scene to an even younger generation, one whose minds were still open and who had no interest or even understanding of the prog-phobic stigma supposedly surrounding these bands.

Your correspondent was one of them. Marillion’s debut album Script For A Jester’s Tear was first played to me as a 14-year-old by a schoolmate of mine who went by the nickname ‘Hippy Seb’. He’d been turned on to Fish’s mob by his prog-loving stepdad, and I was immediately transfixed by the lavish artwork and complex but insidious melodies that really took you on a journey (a 17-minute one, in the case of Grendel). It all seemed way more challenging than the NWOBHM stuff I’d grown up on as a prepubescent headbanger, or the mildly pretentious chart contemporaries like Howard Jones and Nik Kershaw.

And the lyrics! For a teenager just getting stuck into the thick end of the English language, Fish’s multi-syllabic approach to songwriting was something else. OK, so they were regularly dismissed as ‘sixth-form poetry’ in my fortnightly copy of Smash Hits – and sure, they redefine the word ‘verbose’, but what are rock lyrics supposed to be? Middle-aged poetry? The music papers also banged on about their debt to early Genesis, whom I soon checked out and couldn’t decipher much resemblance beyond the stage make-up. But for me and an increasing number of my peers, they really were something else. Most importantly, they were something else your parents (apart from hip dads like Seb’s) and older, supposedly cooler brothers and sisters, just could not, or would not, get their heads around.

This was music that wasn’t immediate – prog is always going to be an acquired taste – and for any kid who likes to have a sense of ‘I got there first’ about their bands, Marillion felt like a real cult concern. They were loved and understood passionately by the believers, scorned and mocked by the philistines who didn’t want to have to put any work into enjoying music.

Cult they may have been, but by the time Kayleigh was only deprived of the No.1 spot by a charity record, Seb and I had managed to convert half our class, with the result that half a busload of us went to see them on tour.

By that time, me and Seb had delved further into the scene and not only got into original prog but also several of Marillion’s contemporaries. And we were far from being alone in looking beyond the chart-hogging likes of Fish and co for our prog thrills.

A young Steven Wilson had his first gig-going experiences at small shows by Solstice and IQ, among others, in his early teens. Synaesthesia mainman Adam Warne’s first gig was an IQ show he attended with his dad. Meanwhile, Graeme Murray was taken aback to learn that Matt Bellamy of Muse later cited Pallas as an influence. There are surely many thousands more who can say the same.

Unfortunately, the neo-prog scene’s time in the spotlight was a relatively brief one. And for that we can put the blame pretty squarely at the doors of Britain’s major labels.

Pallas, Twelfth Night and IQ all signed major deals after Marillion proved that prog could still prove a commercial force to be reckoned with. And at first, the signs were overwhelmingly positive.

“EMI signed us to their Harvest imprint and said they were committing themselves to rock music again,” Graeme Murray recalls. “Building Harvest up to be the great label it was when they had Pink Floyd, Deep Purple and Edgar Broughton. They said, ‘Don’t worry about making hit singles – no pressure, just do your own thing and we’ll support you.’”

Pallas flew out to Atlanta to record their major label debut, The Sentinel, with former Yes and ELP engineer Eddy Offord, but when they returned six weeks later, all was not well. “We came back to find the team who signed us had all been sacked.”

Things were never quite the same for Pallas after that, who felt like they were never much of a priority for the label.

“It was an odd time,” recalls IQ’s Mike Holmes. “Phonogram signed us as a prog band, but then all they wanted was hit singles. The 80s was very singles-oriented. So we could never understand why they signed us in the first place!”

Meanwhile, attempts by the industry to build interest in the neo-prog scene were half-hearted at best. Nonetheless, Elusive Records, a label set up by Marillion manager John Arnison and distributed by EMI, did attempt to unite a mix of established and emerging acts from the scene on a neo-prog sampler album, Fire In Harmony, in 1985.

Unfortunately, of the eight bands featured on that record, only openers Pendragon endured (although some others have reformed in recent years). The folk-influenced, unashamedly hippyish Solstice were offered management from Arnison in 1983, but wary of ‘commercial’ influences, turned him down, as they did a couple of other label deals, before self-releasing their debut Silent Dance in 1984, then splitting a year later.

Haze headlined the Marquee and self-released a debut album in 1984 but split four years later. The then female-fronted Quasar never managed to hold down a stable line-up before they split in 1990. Home Counties outfit Liaison and the Rush-influenced Trilogy were highly regarded at the time but never managed to make it beyond this compilation. Scotland’s Citizen Cain were on the verge of signing a deal with Elusive in 1988 when lead singer Cyrus broke his arm and was unable to play, although they later regrouped to make five further albums.

Norwich’s LaHost, meanwhile, released a solitary single on Elusive, but members such as drummer Fudge Smith went on to play with Pendragon from 1986 to 2006, while keyboardist Stephen Bennett has been a regular collaborator with Tim Bowness in Henry Fool.

At the time, neo-prog also perhaps suffered from the scene not noticeably spreading abroad. There were isolated examples of emerging prog acts in Europe (Hungary’s Solaris, Present in Belgium and Isildurs Bane in Sweden), but no scene to speak of materialised around that time. This despite both Murray and Barrett recalling a thrilling, sold-out show Pallas and Pendragon did at the Amsterdam Paradiso in the late 80s as one of the highlights of that decade. “The first time we played in Holland, it was to over 1,000 people,” says Holmes. “So the audience was clearly out there.”

As the 80s turned into the 90s, the big deals were no longer on the table, and progressive rock’s great Second Wave had completely lost momentum. Pallas were forced to go on indefinite hiatus due to financial constraints, only reforming again in 1999. Twelfth Night split in 1987 after releasing their self-titled 1986 album on Virgin and then being dropped – an experience that rather soured their enjoyment of this music-making lark.

Meanwhile, bands who emerged at the tail end of the neo-prog scene, such as Birmingham’s Ark, Southampton’s Jadis and Bournemouth’s Galahad, found that record labels were no longer remotely interested in signing anything ‘progressive’. They persevered and survived, though, as did IQ and Pendragon, partly due to the latter three of those acts founding their own labels – Avalon, Giant Electric Pea and Toff records respectively.

And in many ways, the invention that necessity gave birth to back then ended up giving progressive music a lifeline with which to build itself back up from the grass roots. Pendragon tapped into the foreign market with the result that they now play big tours across Europe, while IQ’s GEP records is today one of the leading UK prog labels, having been home at various points to Jadis, Big Big Train, Spock’s Beard, John Wetton and Synaesthesia.

Later on, the rise of the internet helped prog forge more effective links with its audience and sell records and gig tickets directly to fans – a process pioneered by the neo-prog bands. It was something Marillion adopted to bring the genre into the internet age when they elected not to sign to a new label in 2000 but instead crowd-sourced the funding for their new album, Anoraknophobia.

Today, 15 years on, and 30 years since the high-water mark of neo-prog, the revitalising spirit those bands injected into the genre is still being felt, not just in the musicians they influenced, but in their own music – IQ, Pallas and Pendragon, for instance, have all made albums over the past year that stand comparison to any in their career.

“Prog has more outlets to get exposure now,” says Graeme Murray. “I was listening to the TeamRock Prog show the other night – you couldn’t have imagined a show like that even 10 years ago. And it’s great having Prog magazine around now too. We never had anything like that around back then.”

Aw, shucks. But far be it from us to take any credit for prog coming in from the cold after all these years. We prefer to salute those brave renegades from 30 years ago instead.

THE TOP FIVE NEO-PROG ESSENTIALS

The key releases that defined and inspired neo-prog in the 80s.

MARILLION

**Script For A Jester’s Tear **

(EMI, 1983)

Undoubtedly the record that put the Second Wave of British Prog on the map. Long-form songwriting and ear-catching musicianship (Steve Rothery’s guitar lines and Mark Kelly’s keyboard hooks have rarely been more sublime) were shot through with a charisma and lyrical bite not seen since the prime of a certain band beginning with ‘G’, to whom Marillion were incessantly compared. The melancholic melodramatics shot through these six compositions were repeatedly offset by Fish’s intense, angst-ridden vocals, touching on heartbreak, heroin addiction, urban isolation and the troubles in Northern Ireland en route.

PALLAS

The Sentinel

(Harvest, 1984)

The Aberdeen outfit’s initial intention to make a concept album out of their Atlantis Suite song cycle was scuppered by their label switching the running order and including more commercial tunes. Yet this is still a fine record, even if the central conceptual narrative is somewhat disjointed by the rearranged tracklisting. The driving synth-rock of Arrive Alive (Eyes In The Night) grabs your lapels with its instant hook and jumpy tempo, then Cut And Run and Shock Treatment reinforce the dystopian sci-fi theme with some gusto. But more lasting pleasures can be found in the sweeping symphonic pomp of final track Atlantis.

** Pendragon **

**The Jewel **

(Elusive, 1985)

Neo-prog had gone fully overground by the time Pendragon released their first full-length album. The upbeat prog-pop of Higher Circles that opens the set reflects the distinctly radio-friendly style it was now adopting, but the plot thickens considerably on the trippy, windswept Alaska and the staccato rhythms of Circus. Yet throughout, the stirring, heart-on-sleeve romanticism that has characterised their best work since this album is already high in the mix, courtesy of Nick Barrett’s distinctly English, folk-influenced vocals, the Moog-heavy melody patterns and piercing guitar excursions.

IQ

**The Wake **

(GEP, 1985)

The Southampton neo-prog survivors’ second album is widely regarded as their defining early statement, and this 1985 long-player manages to marry a distinctive, soaring synth sound with a punky, agitated tempo and some seriously dizzying time signatures. Peter Nicholls’ fragile, uneasy vocal has a drowning-not-waving quality to it that is strangely magnetic, even if his years listening to Peter Gabriel have obviously rubbed off heavily. What really stands out, even 30 years later, is the sheer strength of the melodies, something that has helped IQ endure as a band to this day.

Twelfth Night

**Fact & Fiction **

(Twelfth Night, 1982)

From the eerie, childlike singing that fills the opening bars of We Are Sane, it was clear that this first studio album release from the neo-prog pack was taking a distinctly different tack to the Tolkien-esque textures associated with the original prog movement. The use of samples on that track and This City added spooky atmospherics to the sonic stew, and there were strong hints of Peter Hammill in Geoff Mann’s malevolent, theatrical vocals. Mann would leave the band soon afterwards, and the group would pursue a broader, more accessible style on subsequent albums. But as a startling statement of how the new breed could shake up a supposedly moribund genre, this takes some beating.

Johnny is a regular contributor to Prog and Classic Rock magazines, both online and in print. Johnny is a highly experienced and versatile music writer whose tastes range from prog and hard rock to R’n’B, funk, folk and blues. He has written about music professionally for 30 years, surviving the Britpop wars at the NME in the 90s (under the hard-to-shake teenage nickname Johnny Cigarettes) before branching out to newspapers such as The Guardian and The Independent and magazines such as Uncut, Record Collector and, of course, Prog and Classic Rock.