Pink Floyd's Descent Into Madness

After years of bitter in-fighting, Roger Waters finally left Pink Floyd in 1985. His departure caused rancour... and there was also the question mark over the ownership of their infamous pig

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #85.

In December 1985 Roger Waters informed Pink Floyd’s record companies – EMI in London and CBS in New York – that he had left the band. This did not come as a great surprise to the record company executives. Neither would it have been much of a shock to the 18 million or so Pink Floyd fans around the world who had bought The Wall, had they had known about Waters’s decision.

There had been no activity from Pink Floyd since the release of The Final Cut in March 1983, an album widely regarded as a Roger Waters solo album in all but name. Since then Waters, considered the prime mover of Pink Floyd from the mid-70s onwards, had released a solo album, 1984’s The Pros & Cons Of Hitch Hiking, and had toured Europe and America with a show of Floydian proportions.

David Gilmour, Waters’s chief collaborator in Pink Floyd whose contribution had declined over the previous decade to the point where he’d removed his production credit from The Final Cut, had also released a solo album and toured on a more modest scale – in fact, some gigs were even cancelled due to poor ticket sales. Drummer Nick Mason and keyboard player Rick Wright had also recorded solo albums, although only die-hard fans were aware of them. In fact, virtually nobody was aware that Rick Wright had left the band before The Wall came out in 1979.

In summer 1985 there had been speculation that Pink Floyd might perform at Live Aid but it had never gone beyond that. Gilmour had been the only member of the band to appear at the biggest gig the world had ever seen – as a guest guitarist with Bryan Ferry.

It was, therefore, apparently safe for EMI and CBS to assume that Pink Floyd, one of the biggest-selling bands on the planet up to that point, were finished. Except that they weren’t. There was no confirmation of Pink Floyd’s demise forthcoming from their management; the next information was that Gilmour and Mason were actively considering a new Pink Floyd album. It was the prelude to a titanic struggle between Waters and the remaining members of Pink Floyd over the rights to the name – a battle that was not resolved until after the release of the next Pink Floyd album, A Momentary Lapse Of Reason, in 1987. And even that did not stop the acrimony that has continued intermittently ever since.

The fact that Pink Floyd re-established themselves as one of the world’s leading rock groups without Waters has prolonged the bitterness. But, as Mason put it so memorably: “Roger was fond of saying that no one is indispensable… and he was right!”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

So the sight of Roger Waters reunited with his three former Pink Floyd colleagues at this summer’s Live 8 awareness-raising spectacular in London’s Hyde Park was as momentous as it was unexpected. But any hopes that this was anything more than a one-off have been swiftly dashed. Within a week Gilmour was turning down $150 million offers for the same line-up to play across America and Waters was making snide comments about Gilmour to Rolling Stone magazine.

Like EMI and CBS, Waters believed that Pink Floyd would not continue after he had handed in his notice. He did not think they were capable of making an album without him. He even told them so, to their faces; “You’ll never get it together, you wankers,” is how Gilmour remembers it. This was in August 1986, after Waters had learned that Gilmour and Mason would be making a new Pink Floyd album. Waters’s position was simple: Pink Floyd had expired. Any attempt to continue the band without him was fraudulent. Gilmour and Mason’s view was equally straightforward: no one member had the right to disband Pink Floyd without the consent of the others. And Waters was now an ex-member of Pink Floyd.

The differences were irreconcilable and both sides were convinced that they were right. It’s interesting to note that the last time Pink Floyd’s main creative force had left the band there had been no debate about the rights to the name. After Syd Barrett – who’d written the band’s two hit singles and 10 of the 11 tracks on their first album, 1967’s The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn – had been invalided out of the band with a drug-heightened nervous breakdown, the others carried on regardless, recruiting Gilmour as his replacement.

One big difference between the two events, however, is that in 1985 the Pink Floyd name was guaranteed to generate millions of pounds; in 1968 it was merely thousands. The irony is that Waters’s actions did more to galvanise Gilmour and Mason into continuing Pink Floyd than anything else. It was only after he left that the others considered carrying on. Mason says that Waters could have easily killed off the band by simply staying: “By remaining in it and never doing another stroke of work, nothing would ever have happened.”

Mason admits that he had become resigned to the bitter end of Pink Floyd. The experience of playing on The Final Cut had been so unpleasant that he was not keen to repeat it, and Waters told him he wouldn’t even get the chance. But his lingering doubts occasionally flared up into open discontent, like when he joined Gilmour at his Hammersmith Odeon show in London to play Comfortably Numb, or when he went to see Waters’s Pros & Cons Of Hitch Hiking tour at Wembley Arena and felt “like a rather elderly Peter Pan at the nursery window” as the band played Floyd’s greatest hits without him.

Gilmour retained the confidence of knowing how much of a contribution he had made to the sound of Pink Floyd. His guitar and vocals were responsible for at least half of the memorable moments that most people associated with the band. That didn’t mean he was going to do anything about it, however. And communication between the band members had reached such a low ebb that on the rare occasions when they did meet up they would each go away with different impressions about what had been decided.

“We’d been having these meetings in which Roger said: ‘I’m not working with you guys again’,” Gilmour told one interviewer. “He’d say to me: ‘Are you going to carry on?’ And I’d say, quite honestly: ‘I don’t know. But when we’re good and ready, I’ll tell everyone what the plan is. And we’ll get on with it.’”

Even after Waters had left, Gilmour made no move to resuscitate Pink Floyd to begin with. The catalyst appears to have been Waters’s fury at their refusal to disband the group, at which point Gilmour stubbornly dug in and decided to go for it. “I’ve spent 20 years of my life building a career with Pink Floyd,” he said. “I don’t see why I should have to give that up just because one guy says he doesn’t want to do it any more.”

By the summer of 1986 Gilmour was ready to start a Pink Floyd album with Mason. When Waters realised that his sarcasm and vitriol were not enough to dissuade them, he sent in the lawyers. At the end of October they commenced a High Court action to dissolve the Pink Floyd partnership, declaring that the group was “a spent force, creatively”.

This was the first time the public became aware of the dispute. It was also the first time that it became widely known that Waters was no longer a member of Pink Floyd. A couple of weeks later Pink Floyd replied by releasing a statement that said: ‘The group have no intention of disbanding. On the contrary, David Gilmour and Nick Mason, with Rick Wright and producer Bob Ezrin, are currently recording a new album.’

Gilmour added his own comment to the statement: “The strength of Pink Floyd lay in the talents of all four members. Naturally, we will miss Roger’s artistic input. However, we will continue to work together as in the past. We are surprised at recent claims that Roger believes the band to be ‘a spent force, creatively’ as he’s had no involvement with the current project. The three of us are very excited by the new material and would prefer to be judged by the public on the strength of the forthcoming Pink Floyd album.”

The wording of the statement was deliberately careful. Rick Wright had been invited back by Gilmour and Mason once they had decided to make a Pink Floyd album. However, it made no sense for him to rejoin a band that was facing expensive legal action to dissolve it. In addition, there was the matter of the legal agreement made at the time of his departure that specifically forbade him from rejoining the group. In fact, Wright’s departure created other ramifications that were to prove crucial in the fight over the Pink Floyd name, as I discovered when I interviewed Waters in the spring of 1987 soon after he’d recorded his second solo album, Radio K.A.O.S.. I was in full don’t-mention-the-war mode but it was Waters who brought it up and, after we’d discussed what might or might not constitute Pink Floyd, he told me that when Pink Floyd had signed a new record contract with EMI and CBS in 1982 they had included a so-called ‘group artist rider’.

- The 10 Roger Waters Tracks Every Pink Floyd Fan Should Own

- Pink Floyd dragonfly Ummagumma makes top 10 new species list

- David Gilmour: "I was very happy when Roger didn’t say no to Live 8"

- The 10 heaviest Pink Floyd songs

“This said that the amounts of money paid in advances for records would vary depending on which combinations of people were in the band,” he explained. “And it went through all the various combinations of the band. This was because neither of the record companies had been told that Rick had been fired halfway through the making of The Wall album. We prepared this document so that we could sign an agreement with the record company and then say: ‘Oh by the way, this guy’s leaving’. It was a completely artificial device – as far as I was concerned anyway.”

So, in this document there was a combination of Pink Floyd that didn’t include you? “Yes.”

And you signed it? “Yes. Crazy, isn’t it?” Er, why? “I never thought they’d do it without me. And I’m quite certain that at that time Dave and Nick never thought that they would carry on if I left. It never even crossed their minds.”

Even my non-legal brain could see that this was damaging for Waters’s case. He’d legally written himself out of the band, even before he’d left it. It also meant that the record companies could release a Pink Floyd album that did not feature Waters without fear of legal repercussions. A statement from Waters’s camp a little while later indicated that the battleground had shifted. ‘A dispute with the other members of Pink Floyd is proceeding in the courts to resolve the question of rights to the name and assets of Pink Floyd.’ It concluded: ‘Waters will not again record or perform with Dave Gilmour and Nick Mason under the name Pink Floyd, or at all.’

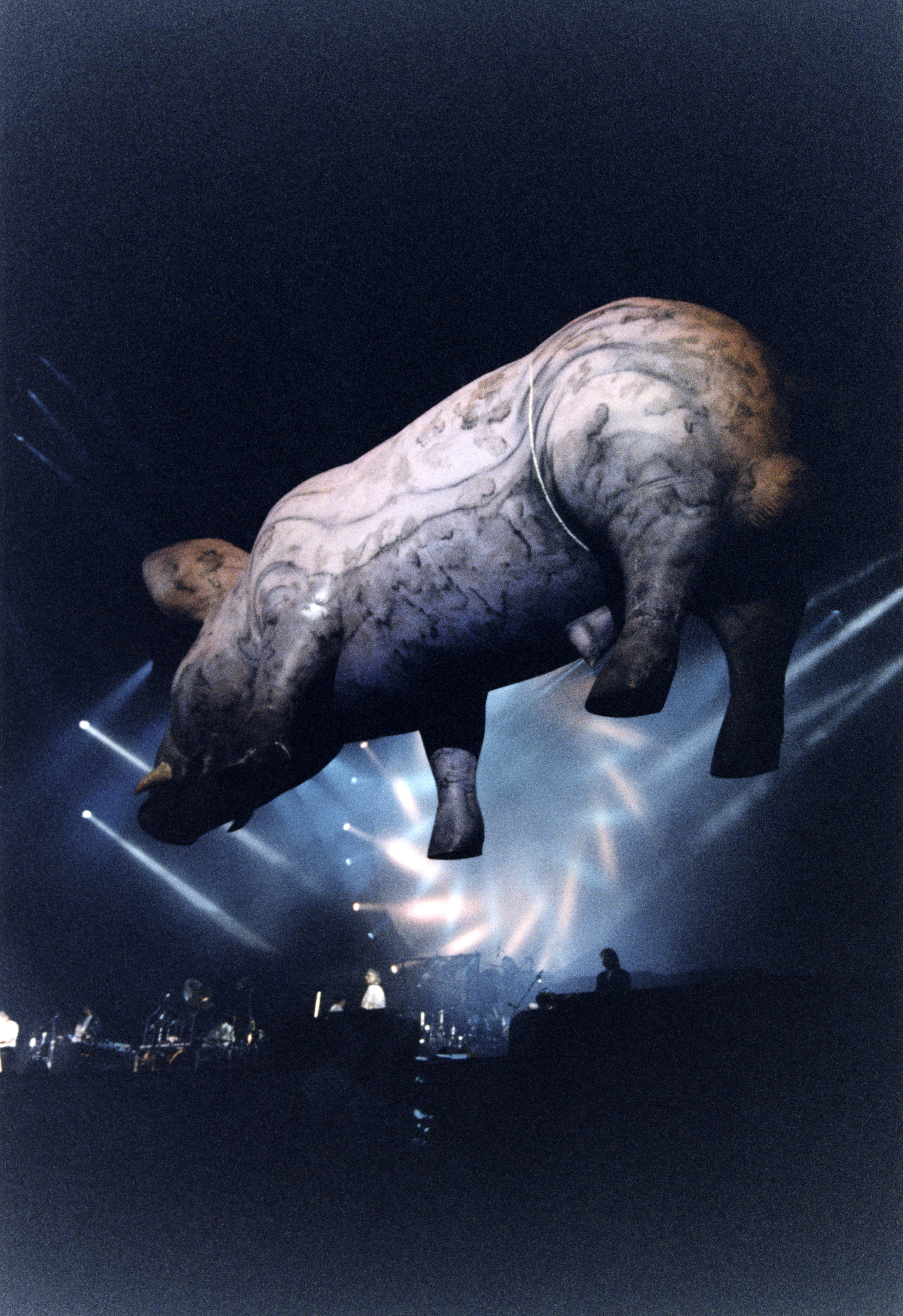

Waters was claiming the rights to the Floyd’s concepts and stage effects on the grounds that they were his creations and nothing to do with the rest of the band. Later that summer I talked to Gilmour about the new Pink Floyd album on his elegant Hampton Court houseboat studio on the Thames, where A Momentary Lapse Of Reason had been recorded. Our conversation was interrupted twice by lengthy phone calls and I could hear Gilmour getting more and more exasperated in the next room/cabin. When he came back the second time he snorted: “It’s the pig. Roger’s claiming the fucking pig!” Lawyers were now trawling through documents from a decade ago to discover just who had commissioned it. It transpired that Waters had. (He’d actually specified a sow. The huge inflatable porker that rose up from behind the stage during the A Momentary Lapse Of Reason tour later that year had the biggest pair of bollocks you’ve ever seen.)

Pink Floyd’s preparations for that tour were dogged by similar rows over the rights to other stage effects, such as Gerald Scarfe’s animations, the massive circular screen and anything to do with The Wall. Promoters for the shows were also threatened with injunctions. Not surprisingly, Gilmour and Mason found it hard to raise the cash to fund the huge stage show they were preparing and had to dig into their own pockets. Mason even had to pawn one of his beloved sports cars.

To add even greater piquancy to the saga, both Waters and Pink Floyd were setting up North American tours at the same time in the autumn of 1987. The opportunity was too good to miss and I fixed up a lightning trip across the Atlantic to catch both acts in different cities.

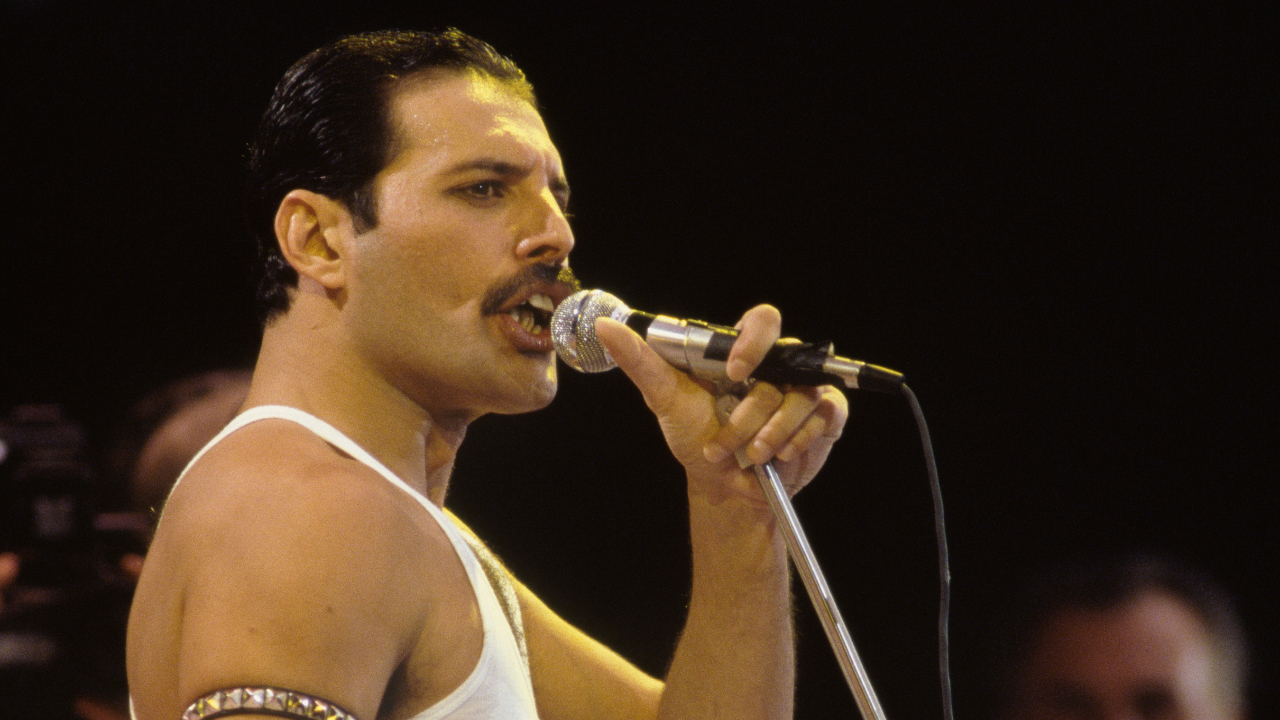

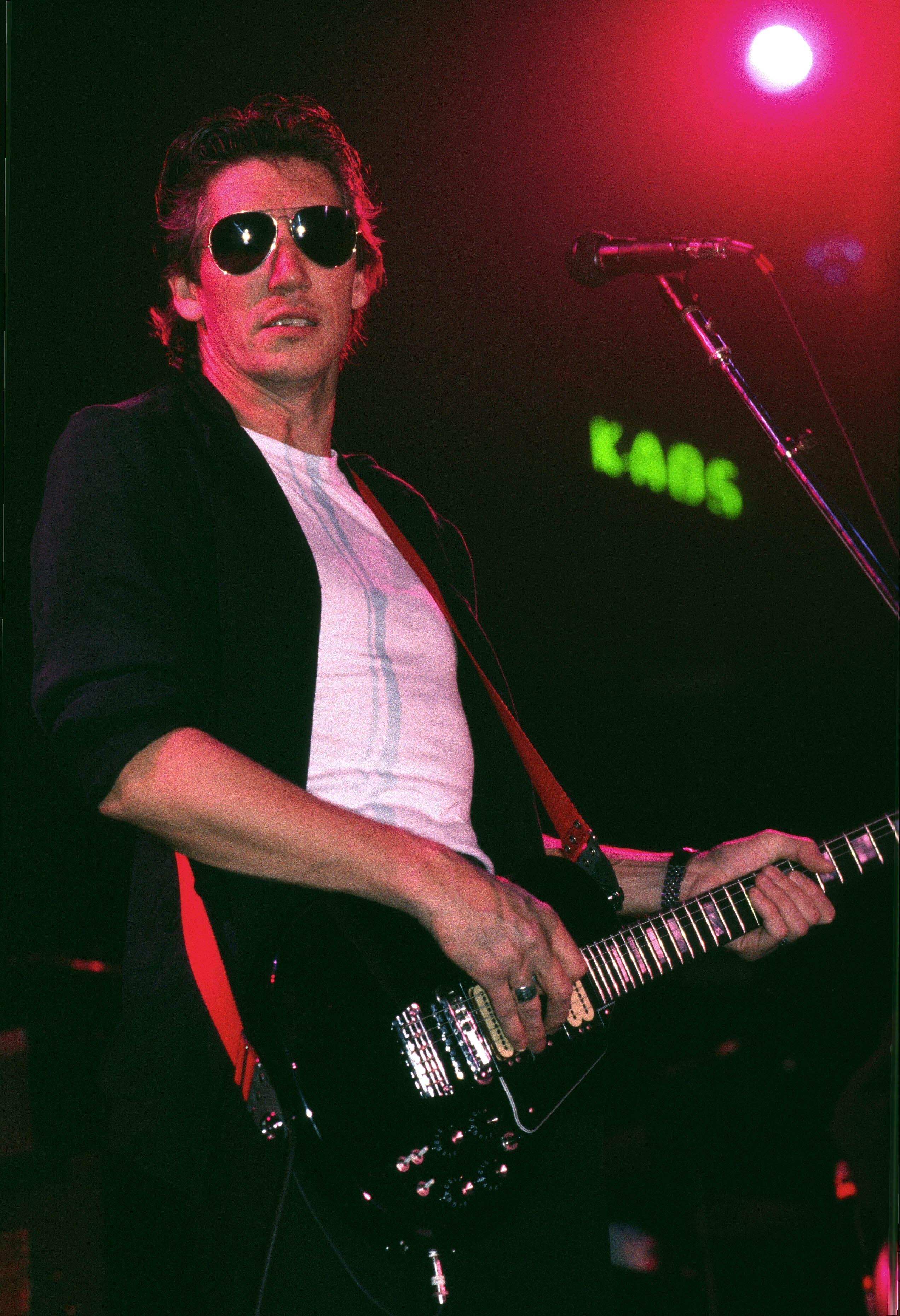

First stop was Los Angeles, where Roger Waters and his Bleeding Heart Band were bringing the Radio K.A.O.S. tour to the 18,000-capacity Forum. There was no mention of Pink Floyd on the billboards, flyers or tickets, although the merchandising stall was doing a brisk trade in ‘Who is Pink?’ T-shirts. The show was a potent brew of rock’n’roll bombast with propaganda, as Waters explored the dense themes of Radio K.A.O.S. – who controls information and the arms race?

Songs from Floyd’s back catalogue came as light relief, although Waters shook them up a little, giving a musical jolt to the familiar riffs on Money, Have A Cigar and Pigs (Three Different Ones). He also delved further back to revive If from 1970’s Atom Heart Mother, as well as the original promo film for Floyd’s first single, Arnold Layne. Shedding his anonymity along with his former band, Waters cut an almost maniacal figure in his sinister dark glasses and tense smile, singing with a nervous intensity. He even took part in a studio phone-in, answering questions from the audience via phone booths near the mixing desk.

It was a provocative show designed to make you think. But this was 1987, Reagan was in the White House and most Americans were no more interested in thinking than their leader was. The on-screen image of a smiling, waving Reagan spliced with a procession of coffins draped with the Stars & Stripes failed to produce much of a reaction. The guy next to me even muttered: “Is this guy some kind of communist?” at one point.

But Waters’s crusading zeal was intact. “I like the theatre of it, and I’m enjoying this tour more than I’ve enjoyed anything. There are hard-core fans coming along with kids who never saw Floyd, which is great. Unfortunately,” he added wryly, “10,000 per cent more are going to see my ex-colleagues – fortunately for them.”

Two thousand miles away, at the Toronto CNE Stadium, was the proof of that – 50,000 fans cheering as Mr Pig poked his snout above the pile of speakers while One Of These Days reverberated around the 360-degree sound system.

Pink Floyd’s $1 million-a-night stadium tour – they first they’d ever undertaken – was a state-of-the-art extravaganza. Behind the massive mixing desk half a dozen people tapped away at computers. When they hit ‘return’, aeroplanes swooped down across the stadium and crash-landed by the stage, lasers pierced the billowing smoke and menacing-looking light clusters stalked the musicians.

Every track on A Momentary Lapse Of Reason – which had only been out a couple of weeks – got an airing, with Learning To Fly and On The Turning Away already sounding like Floyd classics. The greatest hits roamed from Echoes via great chunks of Dark Side Of The Moon to the epic finale with Comfortably Numb and Run Like Hell.

“This show definitely grows on you,” said a relaxed, smiling Gilmour backstage afterwards. “It’s progressing well. I’ve seen a few big shows over the last couple of years and I’ve been distinctly unimpressed.”

“It’s nice to get back to unlimited resources again,” joked Mason, before adding: “It’s been a difficult couple of years but after we’d finished the album I did a series of interviews where the questions cropped up and I had to sort out the issues in my own mind. I think we’ve proved our point with this album and tour.”

Even the normally reticent Wright was mellow enough to wish Waters all the best with his tour: “I really do. I just wish he’d leave us alone to get on with what we’re doing. Some of the claims he’s been making about his role in the group are quite ridiculous.”

Three months later, on Christmas Eve 1987, just over two years after he quit the group, Waters sat down on Gilmour’s houseboat. The pair hammered out a deal that gave Pink Floyd the rights to carry on and Waters the rights to The Wall and various stage effects and films. Mr Pig could stay with Floyd, although he now has an obligatory credit – ‘Original pig concept: R Waters’ – tattooed on his bollocks. The battle was over. Only the cold war remained…

For more Pink Floyd and how Wish You Were Here began a rift in the band they could never repair, then click on the link below.

How Wish You Were Here was the beginning of the end for Pink Floyd

Hugh Fielder has been writing about music for 50 years. Actually 61 if you include the essay he wrote about the Rolling Stones in exchange for taking time off school to see them at the Ipswich Gaumont in 1964. He was news editor of Sounds magazine from 1975 to 1992 and editor of Tower Records Top magazine from 1992 to 2001. Since then he has been freelance. He has interviewed the great, the good and the not so good and written books about some of them. His favourite possession is a piece of columnar basalt he brought back from Iceland.