Neil Peart remembered

Philip Wilding pays tribute to the late Rush drummer

There are no other vehicles out on this highway, the light fading from the sky as a motorbike pulls into view, a lone rider casting a long shadow, there briefly in focus and then gone, heading to the horizon, going nowhere and headed anywhere.

“He’d gone,” Geddy Lee told me years later, years after Neil Peart had lost his 19-year old daughter Selena in a single-car accident as she drove to her university in Toronto. That had been in the August of 1997; five months later his common law wife of 23 years, Jackie Taylor, was diagnosed with terminal cancer. After her death, Neil told Rush to consider him retired and took to the road.

“We didn’t know where Neil was,” said Geddy. “He was just out there somewhere and then very occasionally we’d get these coded postcards that we knew were from him, and that he was alright.”

Neil finally came back to the band to make Vapor Trails and tour again in an era of Rush that Lee calls his very favourite. Perhaps even more remarkably, the man who practised his drums for hours every single day of the year apart from Christmas Day, hadn’t even touched his kit in all the time he’d been away. As the band were putting themselves back together, guitarist Alex Lifeson would stay late after Geddy had left for the day. “And me and Neil would just jam together, get his chops back up, stay late and play.”

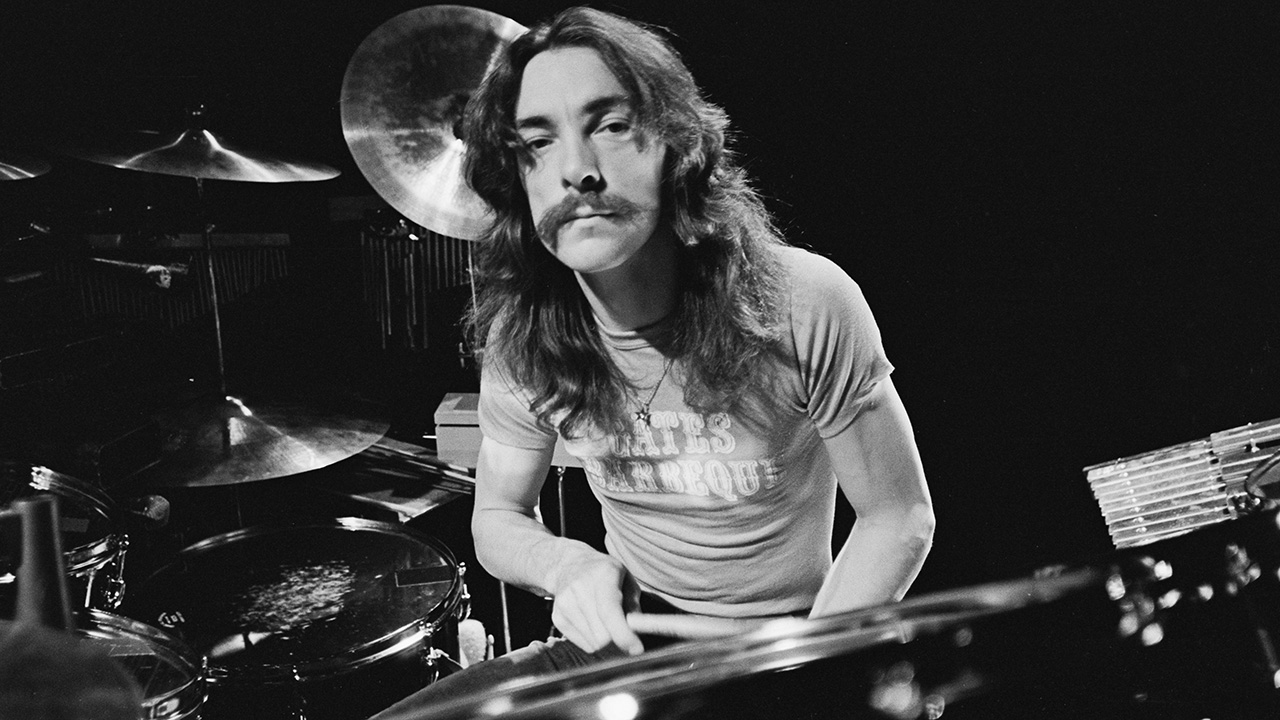

Neil joined Rush in 1974 after the departure of original drummer John Rutsey. “I remember him pulling up and unloading his gear and we thought he was kind of goofy looking,” said Lee. “And we thought we were pretty cool cats! But he started playing and Al and I just sort of caught each other’s eye. He was astounding, he blew us away. After he left this other guy turned up and he was setting up with his sheet music and I felt kind of bad for him because after Neil’s audition he had absolutely no chance.”

Neil walked away from Rush in August 2015, as he began to doubt his ability to play to the demanding high standards he set himself. He had another daughter now and a new wife, and he, more than most, must have realised how time is fleeting and we need to hold on to what we love when we can. I was at those last few concerts with the band, watching their penultimate show at the Irvine Meadows Ampitheatre in Orange County, California from the side of the stage. Not only to enjoy the frantic air drumming and faces pulled by the startled onlookers in the first few rows, but to watch Neil up close, to try and fathom what exactly he was doing.

It was impossible, though. His reddening face was almost impassive, his signature hat perched on his head – how it stayed on in that maelstrom is still a mystery for the ages – but his arms and legs were doing impossible and strange things. Each fill was a recognisable moment of wonder and I, along with every other human being in that open-air arena, paused to get the air drum fill on The Temples Of Syrinx just right. There was something joyous and gloriously unhinged about 16,000 strangers all caught up on the hook of that thundering drum fill rattling across the toms. I’m pretty sure we all thought we were in time too.

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

It was that tour, and one I wish more people could have seen, where the setlist was played out in reverse chronology, starting with songs from Clockwork Angels and ending with Working Man, the stage stripped back to resemble a high school hall, some hours later. Given that the band had to work backwards through their catalogue, Neil had two separate kits around him, his latest set up front and then, as the set progressed (or regressed depending on your viewpoint), the drums would switch around to reveal one of Neil’s older kits from another tour and another time. The older kit was harder to play and less comfortable and less conducive to the setup Neil had grown used to, but he – and this was very Neil – insisted on soldiering on with the older kit for half the set as it brought authenticity to the music. That’s how those songs had been played live before and they would be again.

But I’m getting away from myself; my head is filled with images and memories of him. Drinking 12-year-old Macallan with him at the mixes of Clockwork Angels; him showing off his beautiful silver Aston Martin (as driven by James Bond in Goldfinger), one of many; standing at the Canadian consulate with him in Los Angeles; Neil laughing with the actor Jack Black as they stood out by the pool. Jack looking quizzically up at Neil. “I mean,” he said, “this is officially Canadian ground, but we’re in LA, so, technically, right now, are we in Canada or not?”

But that’s not what I’m trying to tell you. I’m trying to tell you that, as I stood side of the stage and watched him rattle around that impossible drumkit, I could see no weakness in his playing. Rush didn’t feel like some fading power, a band that needed to be stopped before the real lustre was gone, but Neil felt that something was missing in his game, and like his playing of a vintage kit that didn’t quite suit his needs anymore, he understood that stopping was the right thing to do.

I was standing on the roof of the London West Hollywood Hotel in LA, under the blazing Californian sky, people in the pool splashing around behind me, the snaking traffic pulling away towards the horizon. I was waiting for the last show and hoping against hope that Neil would somehow change his mind (I wasn’t the only one – Ged clung to the same forlorn hope for a few months afterwards) and that night’s performance at The Forum in Inglewood would see a shift in how the band worked – fewer shows, more one-off live events – and not the end of the road. I fell into conversation with someone who worked with the band: at the end of each tour, Neil’s drums, not the ones he kept at home in California and gave merry hell to almost every single day, but his touring drums, would go back into storage in, as I recall, Nashville. This one last time, he’d asked that they went home with him. I wasn’t even sure of validity of the story, it sounded apocryphal, too neat somehow, but there in the glare of the Hollywood sky it hit me hard. I felt winded: this was the last Rush show for now and for ever.

That thought was compounded that night. For the first and last time, at the end of the show (one of the most complete and spectacular shows I have ever seen the

band play) and with the sound of a frantic Working Man still ringing in our ears, Neil stepped down from his drum riser and crossed to thefront of the stage to embrace a very surprised-looking Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson. The three embracing as the lights came up, he was saying goodbye to us then, the room felt it, his arm raised in salute to the 17,500 audience, each of us willing him not to leave us, not to leave Rush, but there was the impish grin and he was gone to the shadows and to another life.

That grin. He laughed a lot – more than you might think from his stony countenance or that drilled concentration when he rolled around his drums. He was very close to the South Park creators, Trey Parker and Matt Stone, both of whom were at that final LA show. You only have to check out the extended cut of the brilliant Beyond The Lighted Stage to watch him almost lose consciousness with glee as he turns tomato red and gasps helplessly as Alex keeps the zingers coming until poor Neil is practically on the floor begging him to stop. He laughed well, head back, his looming frame shaking with that self-same laugh.

I made him laugh once – heard and saw that happy exultation – and in a moment where I was trying to do anything but make him laugh. Rush were playing the NEC in Birmingham. It was 2007, their Snakes & Arrows tour. Pegi Cecconi, a long-time friend and associate of the band, and I travelled up from London to see them play. For some reason on that tour Geddy had foregone any usual sort of backline and had settled on a row of chicken rotisserie machines. During the set a roadie would be sent onstage to baste Geddy’s chickens, which sounds far filthier than it was.

It came as a complete surprise to me when I was forced onstage in a pinny and chef’s hat – it was that or something that looked like a rubber chicken so I opted for the hat. Armed with a basting bowl and brush, I was pushed up the surprisingly steep stairs to the stage.

To compound my fear and confusion, Rush had just broken into The Spirit Of Radio, a single I remember buying as a teenager one Saturday morning back home in Wales. So, no pressure then, all of this manifesting itself in my frontal lobe, as Alex pealed out that extraordinary riff out into the dark and cavernous NEC hall. The stage was huge, like a football field covered with amps and drums. To my right and just off stage, Pegi could be heard laughing out loud from the shadows, screaming my name in a way that I’d like to think was done with at least some affection.

I basted Ged’s chickens with due diligence, opening up the smokey glass rotisserie doors, adjusting the heating knob and moving along the stage. It was only then and out of the corner of my eye, that I caught sight of the furious, pumping machine that is Neil Peart up close. His legs were like pistons, arms a familiar blur, his face stony with concentration, he looked like a steam train that was locked in place. And then, just as I reached the last rotisserie, he turned his head towards me, burst out laughing and exclaimed: ‘Phil!’ His metre didn’t shift, not a fill missed, but there, just for a moment, in that swirling darkness punctuated by pulsing stage lights, he grinned and looked at me like he’d just caught me stealing apples in his yard. It was a moment of such beauty and stillness that it still makes me pause now. To be there then, in that moment, happy to have stood briefly in his light, but the memory of that laughing face, his dizzying skill now gone forever, makes my heart break over and over.

Absurd now to think that his energy is stilled and gone forever. I’m furious at the universe for taking him away from us, that something called glioblastoma (an aggressive form of brain cancer), should have diminished all that power and eventually his light. His warm and generous energy snuffed out, his intangible skills finally stilled. I’ll leave you with this: we were talking once, Neil and I, for some long-forgotten interview. And as was often the way, the subject of his wanderlust and unique way of touring – transporting himself to the show on his motorbike and meeting the band at the venue – came up.

“I love what the bike gives me,” he said. “The injection of life, freedom, engagement with the world, and it’s still something that I love: the anonymity I have on the motorcycle. I stop at a diner or at a gas station, I have wonderful encounters with people at rest areas at the side of the road… these moments that are just person to person. Those are the moments, that is how I live best.”

And that’s how I like to think of him, still out there somewhere. A moment of grace in another person’s day, thumbing through a batch of postcards in a corner store, wondering which one to send out into the world next, to let us all know he’s okay.

Philip Wilding is a novelist, journalist, scriptwriter, biographer and radio producer. As a young journalist he criss-crossed most of the United States with bands like Motley Crue, Kiss and Poison (think the Almost Famous movie but with more hairspray). More latterly, he’s sat down to chat with bands like the slightly more erudite Manic Street Preachers, Afghan Whigs, Rush and Marillion.