"If someone tries to start a fight with you, put them down as fast and nastily as you possibly can": The wild life of The Who's combustion engine, John Entwistle

Delivering a deafening but dextrous bass-in-your-face assault, John Entwistle was a key part of The Who’s sound – and also their chemistry. This is his story

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

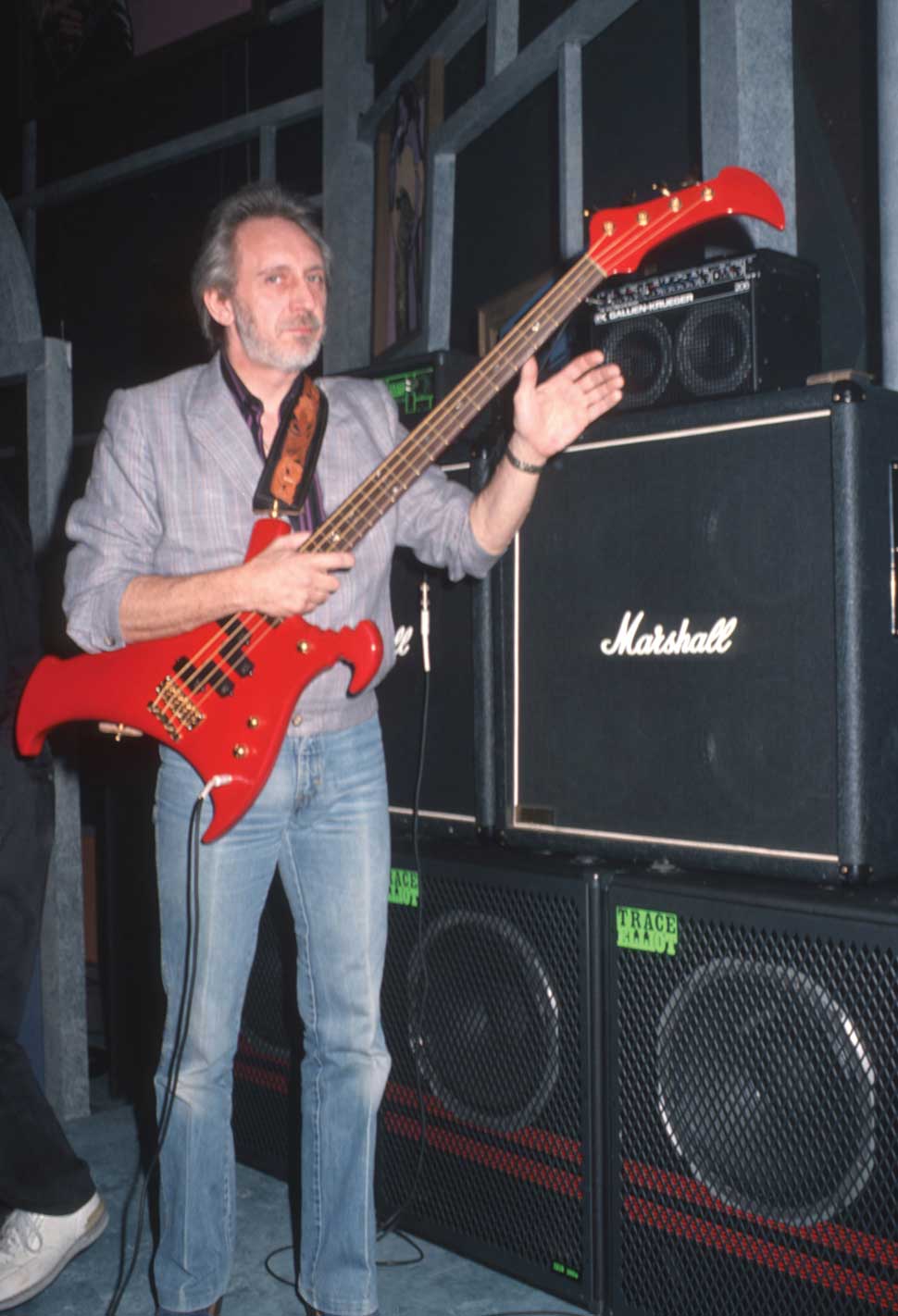

There were good and sound reasons for the two enduring nicknames The Who bassist John Entwistle was given: The Ox and Thunderfingers. The former was bestowed on account of his iron constitution, the other because of the speed, power and volume at which he played the bass guitar. In each of these respects, and most others too, it would be entirely accurate to say that John Alec Entwistle never did things by halves.

Footage of the last UK gig he played with The Who survives on YouTube. It was at London’s Royal Albert Hall on February 8, 2002, although in respect of the key details of his performance, it could have been any Who show from the preceding 30 years. As always, he’s standing stage right, erect as a soldier on parade, rooted to the spot in his Cuban heels, as if the better to anchor the band’s restless, volatile sound. His only appreciable movements are from his hands and fingers, which attack the strings of his bass like demented spiders.

The electric bass was still a relatively new instrument when Entwistle took it up in the early 60s, the potential of it latent and uncharted. He went at it with the zeal of a Victorian explorer, testing every aspect of its range and then charging on beyond those boundaries.

“John was a remarkable player,” says Bob Pridden, The Who’s long-serving soundman. “It was Bill Wyman who said he was the Jimi Hendrix of the bass, which is a good way of explaining what he did. The sound he got was unique. If you listen now to the early Who records, the bass is the lead instrument. And he was bloody loud, too.”

Entwistle himself was typically blunt about the formidable racket he made. “I just wanted to be louder than anyone else,” he once said. “I really got irritated when people could turn up their guitar amps and play louder than me.”

Not that there was ever much chance of that happening. Famously, his bass rig grew to be so towering and such a sprawl that among Who insiders it was known as Little Manhattan. Roger Daltrey was forever badgering Entwistle to turn down the volume on stage, the Who’s frontman claiming he wasn’t able to properly hear himself sing. Usually, Entwistle would stare implacably at Daltrey – and then turn it up instead.

More than his playing and the volume that went with it, Entwistle was his own influential force within The Who. He was the only member to have had any formal musical training, and was also proficient on multiple brass instruments, as well as being an adept arranger. When he wrestled the platform from Pete Townshend, he was also a capable songwriter.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Starting with A Quick One in 1966, almost every album that Entwistle made with The Who included one or more of his songs. They were distinctive for being gruesome, steeped in pitch-black humour and populated by such characters as degenerates, depressives, prostitutes and, in one memorable instance, an arachnid named Boris.

That latter song, Boris The Spider, was the most requested that The Who played on stage, which piqued Townshend no end. Outside of The Who and on a succession of solo records, Entwistle expanded on his pet macabre themes and alighted upon others just as darkly twisted.

The smartest of the band in a fashion sense, he was first among them to sport a Union Jack-emblazoned jacket when The Who were trying to pass themselves off as trailblazing Mods. More generally, he was never less than immaculately attired, having very early on established his own distinctive look and style.

A talented sketch artist, he drew the cover art for the band’s 1975 album The Who By Numbers, expertly caricaturing each of them: Daltrey all hair, Townshend all nose, drummer Keith Moon deranged-looking, and himself looming over the others in the background of the frame. In later years he would merrily point out that his cover had cost The Who just £30, whereas the bill for the one Townshend commissioned for 1973’s Quadrophenia cost £16,000.

On YouTube there’s more revealing footage from 2002 of Entwistle with The Who. This was captured on a handheld camera and dates from later that summer when they were rehearsing for a forthcoming US tour. Five of them are crammed into a small sound studio, Zak Starkey on drums and John ‘Rabbit’ Bundrick on keyboards joining Entwistle, Daltrey and Townshend. For the most part, Entwistle sits in a plastic office chair to play.

Even taking into account the grain of the cheap film stock, he seems drawn and pallid, his skin the colour of burnt ash. He was taking medication for high blood pressure, and years of aural abuse had ravaged his hearing, but at a certain point Townshend conducts them into I Can See For Miles, perhaps The Who’s greatest song, and Entwistle is visibly roused. Rising from his seat, he detonates an explosive but shifting rhythm line that blasts through and pulls at the body of the song, so that it sounds all at once familiar but different, steadfast but unpredictable. Which is to say, just like Entwistle himself.

Less than two weeks later, on 27 June, he was gone, found dead in a Las Vegas hotel room after a night spent carousing. He was also known among The Who’s inner circle as the Quiet One, but erroneously in this instance.

Townshend and Daltrey got on stage at the Hollywood Bowl without him on July 1, the opening night of the planned tour, with session ace Pino Palladino filling in for their fallen bandmate. Addressing the audience that night, Townshend reflected: “It is difficult. Pino came and rescued us. Even without that huge harmonic noise that usually comes from that side of the stage, it sounds pretty good to me.”

It did indeed sound pretty good, in a slick, well-drilled and professional sense. It wasn’t, though, the wild, barely contained and all-the-more-thrilling-because-of-it tumult that The Who were able to summon up on any given night with Entwistle and also Moon with them. At such times they were nothing so much as a force of nature. And even though Townshend and Daltrey have kept on keeping on, The Who aren’t, and nor could they ever be, anything like the same band now.

John Entwistle was born on October 9, 1944 at Hammersmith Hospital in London. It became part of Entwistle family legend that just as the baby John was delivered, a payload dropped by a German bomber landed down the road from the hospital, and that soon afterwards John was found to have a birthmark shaped like a bomb on his calf.

He was the only child born to Herbert and Queenie Maud Entwistle. His father played trumpet, and his mother piano. They separated not long after bringing him into the world, and the young Entwistle went to live with his mum, and later stepfather, at his maternal grandparents’ house in South Acton. He was a solitary, reserved child, but one animated by music.

At five and six, his grandfather would take him to the local working men’s club, where John would stand on a stool and sing Al Jolson standards while his grandfather passed around the hat. At seven his mother got him a piano teacher who, according to Entwistle, was “really ancient. She had a room full of cats, and fingers like spoons.”

He stuck at piano for four years before switching to his father’s instrument, the trumpet. In 1965 he passed the 11-plus exam and went up to Acton County Grammar School, from where he auditioned into the Middlesex Symphony Youth Orchestra. The orchestra picked from the cream of the region’s young talent, but was over-endowed with trumpet players and so once again he changed over, this time to French horn.

In his second year at Acton County, Entwistle made the acquaintance of Townshend, his junior by seven months. Intense and self-absorbed, Townshend was marked out by his prominent nose. He had recently taken up the banjo, and the two schoolboys started playing together in a fledgling group they named The Confederates, their repertoire made up of easy-listening trad-jazz hits of the day. The Confederates rehearsed diligently, but managed just one public engagement, playing two instrumental tunes to 10 people at the Acton Congregational Church Youth Club on December 6, 1958.

Deciding the burgeoning sound of rock’n’roll offered more fruitful long-term prospects, Entwistle next took up the guitar. In this endeavour he was disadvantaged by the size of his fingers, which were too big for him to easily manipulate the six strings. A solution was suggested to him by Duane Eddy, the twanging American rockabilly guitarist then breaking through to a British audience. Eddy’s chunky rhythm parts on tracks such as Rebel Rouser could easily be replicated on the bass, its four strings so much better adapted to Entwistle’s particular needs.

Entwistle didn’t have the money to buy a bass, so he set about making one. He acquired a piece of mahogany, had a carpenter carve it into the shape of a Fender Precision body, and fretted the neck and wired the instrument himself.

He was shouldering this new bass down the street one day when he came across another fellow Acton County pupil, Daltrey. ‘Big, bad Roger’ by reputation, Daltrey was the school’s resident hard nut and troublemaker. He would soon enough be expelled, and at 15 go on to work as a labourer on a building site. He was also the leader and lead guitarist of the best of the school’s clutch of bands, The Detours. Daltrey tempted Entwistle into The Detours with the enticement that they were already pulling in good money. In turn, Entwistle convinced Daltrey to jettison the band’s resident rhythm guitarist and bring Townshend in instead.

As Entwistle was settling into The Detours, he met a third person at Acton County who would be significant in his life. He had the school having recently gone co-ed to thank for it, because dark-haired, 13-year-old Alison Wise was among the initial intake of girls to Acton County. The two of them first got talking at the local church.

“He used to play the bugle in the Boys’ Brigade and march behind with the band,” the future Alison Entwistle recalls now. “My first impression of him was: ‘You’re rather lovely.’ He was very mischievous at school, always leaving notes behind in the desks, and a very good artist too. He did a quite wicked caricature of my twin sister that was put in the school magazine and she never forgave him.

“Our first date was at a Boys’ Brigade concert at the Albert Hall on January 28, 1959. I remember his gran and granddad being gorgeous and that John protected his mum, because his stepfather wasn’t a very nice character at all. His actual father was lovely, but he was living in South Wales.”

By the time Entwistle and Townshend left school in the spring of 1961, The Detours had got themselves a booking agent and were playing around London for five or six nights a week. Like Townshend did, Entwistle could have gone on to art college or music school, but the family home needed a second income, and so he took a job at the tax office where his mother was also employed. The work was dull, menial, and in any case, Entwistle had his mind on the band’s business, and often as not turned up at work shattered from gigging the night before.

The British music scene was on the cusp of a radical shift, one that might offer a willing young lad like Entwistle untold opportunities and rewards. In October 1962, The Beatles released their debut single, Love Me Do, and at a stroke ushered in a new, more exciting and youthful era. Across Britain, it was as if the world had turned from black-and-white to colour. Out of the traps in London came such strutting, fresh-faced groups as the Rolling Stones and The Kinks. The members of The Detours couldn’t help but reason that playing music could now be an attainable career option. But, at Townshend’s cajoling, first they had to measure up to the emerging competition. This, among other things, meant beefing up their sound.

To help them do that, Townshend sought out Jim Marshall, proprietor of the Marshall Music Shop in nearby West Ealing. Marshall was known for his enthusiasm for encouraging aspiring young bands by kitting them out with gear at a reasonable price. He was also in the process of developing the amplifier that would carry his name and make his fortune. One of Marshall Amplifiers’ first customers was John Entwistle.

“John was very happy with his new cabinet of four twelve-inch speakers intended for bass guitar,” Townshend wrote in 2012. “I was less thrilled. John, already very loud, was now too loud. I bought a second speaker cabinet and powered it with a Fender Bassman head. John bought another speaker cabinet to stay ahead of me. I quickly caught up with two Fender amplifiers. John and I were engaged in a musical arms race.”

After seeing an Irish band also called The Detours perform on the TV talent show Thank Your Lucky Stars, in February 1964 Entwistle’s Detours became The Who. The name was suggested by Townshend’s flatmate, Richard Barnes, and since none of them could come up with anything better, it stuck. Or at least it did until they fell under the influence of Peter Meaden. A fast-talking, pill-popping music-biz operator who for a spell had been the publicist for the Stones, Meaden became The Who’s first manager.

It was he who coaxed them into going Mod, hitching to the youth movement that was then taking root in the clubs and coffee bars of their West London stomping grounds. Meaden packed them off to the barber’s to get crew cuts, and dressed them in striped jackets and tight drainpipe pants, de rigueur for any self-respecting Mod ‘face’.

He also had them change their name yet again, to the High Numbers. As the High Numbers they recorded their first single, Zoot Suit, for the Fontana label. When it failed to dent the UK Top 40, Meaden’s hold on them was loosened and they went back to being The Who.

Along the way they had also built up a loyal following doing repeat gigs at local venues such as the White Hart Hotel in Acton and the Goldhawk Social Club round the corner in rougher Shepherd’s Bush. One Thursday night at another of their regular haunts, the Oldfield Tavern, a drunken kid approached the stage and yelled up to the band that his mate could play much better than the jobbing drummer they were using.

“So he brought up this little gingerbread man,” Entwistle remembered. “[He had] dyed ginger hair, a brown shirt, brown tie, brown shoes.”

They invited this odd-looking interloper up on stage and on to the drum stool, and set him the challenge of keeping up with their breakneck version of a Bo Diddley tune, Road Runner. “He played it perfectly,” Entwistle said about this kid, called Keith Moon. “He broke the session drummer’s bass drum pedal that he’d had for twenty years and mucked up the hi-hat as well.”

Whatever the indefinable formula required for making a great band, key to it in The Who was the savage fusion that resulted from pairing Keith Moon with Entwistle in the rhythm section. Moon’s drumming was propulsive but manic, his timekeeping at best erratic and sometimes non‑existent. Yet Entwistle was solid enough to keep him in check, and so good that he was also able to play around and about him, meaning that even the simplest Who songs were elastic and hard to pin down.

It was also true that Entwistle managed and conspired with the combustible Moon better than the other two. To begin with at least, Daltrey was more liable to punch the errant Moon, while Townshend’s attitude towards him forever veered from benevolent tolerance to seething resentment.

“Keith must be the hardest drummer in the world to play with, mainly because he tries to hit every drum at once,” Entwistle once observed. “And if you try and fit in with one of his beats, you have to play like him… all over the place.”

“Keith was totally mental, but to start with actually a loveable chap,” says Alison Entwistle. “He was very sweet, but fame and everything that went with it turned him a bit. John and Keith grew to be very close, and I also became good friends with Keith’s wife, Kim. Not that they had fame overnight. It was such a gradual process. When they first went on the road, they had an old van and had to carry their own equipment around. It was hard work and very tiring for them.”

Through the grind of one-night stands around London and further afield to satellite towns such as Watford, The Who evolved a stage act quite unlike any of their contemporaries. Daltrey began to brandish his microphone lead like a whip, Townshend assailed his guitars with a windmill arm, or smash them to smithereens on the small stages. Behind those two, Moon was a whirling dervish, Entwistle his counterbalance, unmoving as a statue.

Altogether, there was about The Who something feral and violently dangerous, and this only made them all the more awesome to behold.

Eventually they got picked up by another couple of young-buck managers on the make, rough-edged Chris Stamp, whose elder brother was actor Terence Stamp, and urbane Kit Lambert, son of composer and conductor Constant Lambert. Stamp and Lambert put them into the studio with The Kinks’ producer, Shel Talmy, an expat American, and in January 1965 they debuted on record as The Who with a Townshend original, I Can’t Explain. A spring-heeled, Kinks-esque burst of energy, it featured an uncredited Jimmy Page on rhythm guitar, although his contribution was shunted to the sidings by the freight-train rumble of Entwistle’s bass. The single rose as high as No.8 on the UK chart.

The follow-up, Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere, also made the Top 10. But it was the third, another song of Townshend’s, that truly lifted them off.

My Generation started life as a slow blues, but was transformed in the studio into a short, sharp kick in the teeth. The catalyst for this was the decision to underpin the track with a bass solo. Entwistle’s fluid, somersaulting part arrives 55 seconds in and sends the track hurtling on to a headlong crash of guitar, drums and more bass, with Daltrey’s stuttering lead vocal meant to replicate the amphetamine-rush speech patterns of the Mods. My Generation was almost impossibly exciting.

“To get the right effect I had to buy a Danelectro bass, because it had little thin strings that produce a very twangy sound,” Entwistle explained of his pivotal contribution.

Such was the force he applied to them, he broke three sets of these strings. In the end he nailed the solo on the fifth pass.

My Generation rocketed to No.2 in the UK in the winter of 1965. More significantly, here for the first time were the very different, conflicting personalities of The Who coming together on vinyl as a single, eruptive compound.

“John was an easy-going chap and really quite down to earth,” says Bob Pridden, who went to work for The Who soon after. “The atmosphere around the band, though, was always the same. It was like going to war every day. They were all total opposites, and when they came together, it blew up. But that energy was what made them so formidable. My God, they were unbelievable and also terrifying.”

To other musicians of the time, the hub of The Who’s power was obvious and rested within the collisions between Entwistle and Moon. When Jimmy Page and another of The Yardbirds, Jeff Beck, each separately imagined forming a new, more heavyweight band in the spring of 1966, both of them considered poaching both men from The Who. That idea for the nascent Led Zeppelin floundered, and instead Moon, and much more particularly Entwistle, set about expanding their spheres of influence within The Who.

Since Townshend and Moon’s destructive tendencies towards their instruments – and in the case of Moon, inanimate objects in general – was proving so ruinously expensive, Kit Lambert was made to try to find a way to ease The Who’s financial burdens. One upshot of this was a publishing deal that he signed the four members to and that required each to write two songs for the band’s second album, A Quick One.

Neither Daltrey nor Moon made too much of an effort, but Entwistle took this new challenge seriously. He wrote and recorded his first song, Whiskey Man, in the makeshift studio he had installed into the box bedroom of the house he’d bought in Ealing. A cautionary tale about the demon drink, it was a decent stab at the kind of gently psychedelic pop that was then in the ether. The other song Entwistle contributed to the album was something else entirely.

“I still had one more number to write, so I went out and got drunk down the Scotch Club with Bill Wyman,” he said of its genesis. “We started talking about spiders and the way they frighten people, and that gave me the idea.”

Boris The Spider emerged from the recesses of Entwistle’s mind as a freak show version of a basic four-four rocker. Against his own booming bass, he contemplated the titular spider climbing his bedroom wall, singing the choruses in a bronchial grunt that mimicked Spike Milligan’s Goon Show character Throat, and ended the song with poor Boris squashed with a hardback book. It proved to be the album’s most diverting moment, as sinister as it was hilarious.

With A Quick One completed, Stamp and Lambert turned their attention to America, where there was real money to be made. The Who made their first trip across the Atlantic in the spring of 1967. They were to play a 10-day run of shows, five 30-minute slots daily at the RKO Theatre in New York City, on a bill that also included Mitch Ryder and another British band on their first US visit, Cream. Checking in to the Drake Hotel, roommates Entwistle and Moon giddily adapted to their new surroundings, ordering up bottles of vintage champagne and brandy, and platters of lobster and caviar, running up a massive room-service bill. But that barely registered as The Who began to cut a swathe across the US.

The New York residency won them rave reviews from the American rock press, and over on the opposite coast that June they vied with Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin as the breakout stars at the first of the era’s defining open-air festivals, Monterey Pop. Out West they also made their US TV debut, on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, a good-natured variety show hosted by a pair of genial folk satirists. At the finale of My Generation, Moon dynamited his drum kit, the explosion sending cymbal shrapnel slicing through his arm and causing bedlam in the TV studio. The senior Smothers, Tommy, attempting to restore calm and order, walked onto the stage set with his acoustic guitar, only to have Townshend snatch it from him, hurl it to the floor and put a foot through it for good measure.

In the midst of the carnage, Entwistle alone seemed utterly nonplussed, standing apart from the others with a stoic, maybe even bored expression on his face. In the context of this most unhinged and dysfunctional of bands, the very fact that he appeared to be relatively normal made him unique.

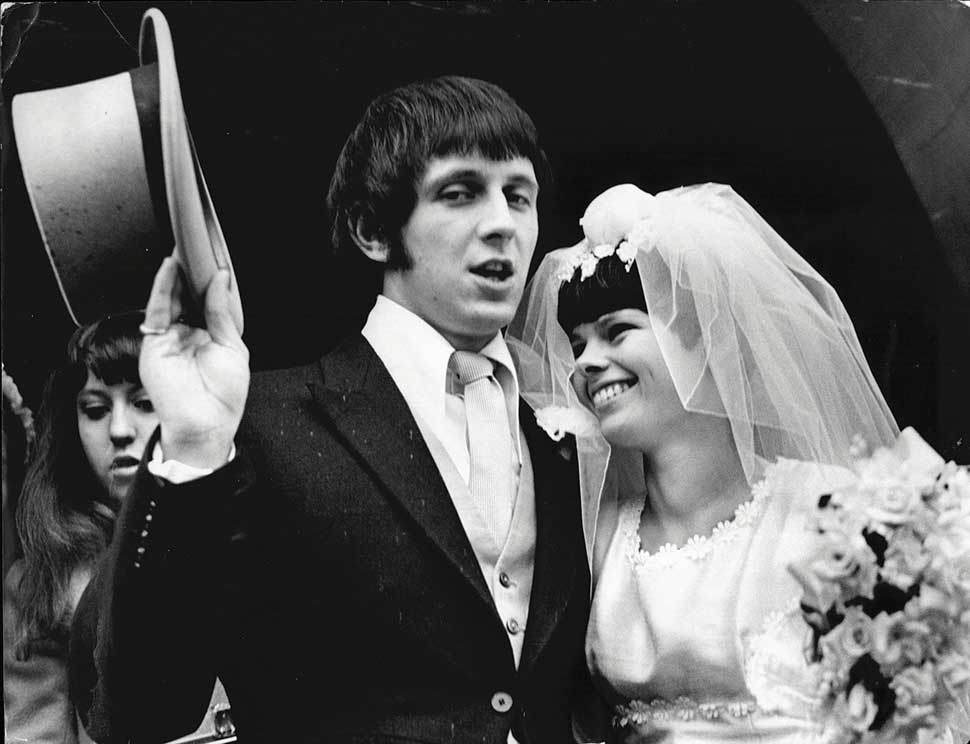

Back home in England, Entwistle married Alison that summer. He had proposed on his twenty-first birthday. Entwistle’s dad was his best man, and afterwards the newlyweds went to live in the Ealing semi-detached – a marked contrast to the 400-year-old Berkshire country cottage and Georgian pile in leafy Twickenham that Daltrey and Townshend respectively had recently acquired for themselves. In this regard, Entwistle’s excesses came later.

“In the downstairs cloakroom we had a two-way mirror and John liked black ceilings,” Alison Entwistle explains. “Apart from that we had a very traditional home, really. It would be horrible when he would have to go off on tour. We used to write letters to each other. He was a very romantic man.”

Until the end of the 60s, The Who toured relentlessly, and when they weren’t on the road they were in the studio. Their next album, 1967’s The Who Sell Out, was made on the run and was a building block towards Townshend pulling off a full-blown concept album. The individual tracks were broken up by spoof radio jingles for products such as Medac acne cream and gleefully recorded by both Entwistle and Moon.

Entwistle’s song for the record, Silas Stingy was as creepy as a Brothers Grimm fairy tale, and on the cover he appeared as his own comic book creation, Tarzan-like in leopard-print furs, a Teddy Bear clutched in one hand, a blonde ‘Jane’ on the other.

When next time around Townshend did deliver his grand rock opera, Tommy, Entwistle was able to immerse himself in that too, even though he confessed to having had “absolutely no idea” what the story of the deaf, dumb and blind kid was all about.

When Townshend needed two songs to go with two of his most unpleasant characters, Tommy’s abusive ‘Uncle’ Ernie and bullying cousin Kevin, he turned to Entwistle for help. He got from him two tunes as jaunty-sounding as old-time music-hall standards, but stuffed full of lyrical horrors. “Pete felt he couldn’t write nearly as nasty as me,” Entwistle said of them. “So I wrote Fiddle About that evening, and Cousin Kevin I based on an old school chum of mine.”

To great acclaim, The Who took Tommy out on tour, their soaring status symbolised by them graduating to playing sports arenas in America and later on opera houses in Europe and the Metropolitan Opera in New York. The two principal gigs of the tour took place in a farmer’s field in upstate New York, and then in the poky refectory at Leeds University.

The Woodstock Music & Art Fair went ahead on Max Yasgur’s 600-acre dairy farm on the weekend of August 15-17, 1969. Having 400,000 people invade the site and with the provision of primitive facilities to sustain them, Yasgur’s land was turned into something as hellish as a combat zone.

The Who took to the Woodstock stage in the pre-dawn hours of the third day, and followed a ragged set from Janis Joplin, and one of febrile, narcotic funk from Sly And The Family Stone that lifted the spirits of the by now exhausted mass of people. The Who proceeded to play like men possessed, which in a sense they were, since someone had spiked the backstage drinking water with acid. Daltrey later said it the worst show they ever played.

Townshend had got Bob Pridden to record every date of the American tour for a planned live album, but then couldn’t be bothered to wade through the tapes. Instead, when they returned to England two smaller-scale shows were hastily arranged for the purpose, at the universities of Hull and Leeds. When technical problems marred the former, it all fell to the latter to deliver.

Rush released in May 1970, Live At Leeds captured The Who in full flight. Entwistle drove them from the front seat, his bass so imposing it made The Who sound heavy metal even before the term had begun to be widely used.

While Townshend laboured over a follow-up to Tommy, Entwistle went off and made his first solo album, with Keith Moon tagging along to play drums. Smash Your Head Against The Wall – complete with a garish cover photo of Entwistle wearing a death mask transposed over an X-ray photo that showed the lungs of a terminally ill patient that he had somehow obtained from his doctor – was solid, straight-ahead rock with a side order of the bizarre. Included were songs titled Pick Me Up (Big Chicken) and Ted End.

Back with The Who, he added the bawdy My Wife to what eventually became their most complete album, 1971’s Who’s Next, singing in a carefree manner: ‘I ain’t been home since Friday night, and now my wife’s coming after me/Give me police protection…’

Who’s Next and the tour for it were both huge successes, and at last riches poured into the band’s coffers. Entwistle indulged himself now, moving with Alison into a bigger house in Ealing and starting to collect cars – even though he didn’t have a driver’s licence – and other paraphernalia. They had a son, Christopher, whom he doted on, though he bemoaned the state of domesticity on songs such as Apron Strings and The Window Shopper on his so-so second solo album, 1972’s Whistle Rhymes.

“We didn’t have any money and then all of a sudden we had a lot, and it went to John’s head a little bit,” says Alison Entwistle. “He was absolutely reckless with money, would spend it like water. He wouldn’t go out and buy one pair of boots, but half a dozen at a time. When we first had Christopher, we had a nanny and there were times that I didn’t know where her wages were coming from. It was quite worrying.

“They always called him the Quiet One, but he wasn’t. He could do far worse things than Keith, he really could, and depending upon how much he’d had to drink.”

His music kept Entwistle focused and gave him a reason for being, but the reassuring routine and momentum of The Who’s early years began to wane, the gaps between albums and tours getting longer. He made two more solo albums in quick succession: Rigor Mortis Sets In in 1973 and Mad Dog, released in 1975, both knockabout pastiches of 50s rock’n’roll, neither of which was a hit.

At the same time, the state of the band became more fractious, with distance and suspicion dividing them. Daltrey had their accounts audited and subsequently engineered the firing of managers Chris Stamp and Kit Lambert, both of whose approach to such things had long been haphazard. The more businesslike Bill Curbishley took over the reins, and gave Townshend scope to mount a second rock-opera, Quadrophenia, for which Entwistle spent weeks arranging horn parts.

Touring that album in 1974, Townshend cut a wayward, antagonistic figure. The Who were trying out on-stage backing tapes, but the technology was new and liable to malfunction, which infuriated Townshend. Raging at one stop on the UK leg, he swung a hopeless punch at Daltrey, who responded with a single blow that knocked him out cold. Even Entwistle’s nerves got frayed. Frustrated one night by Daltrey’s compulsion to explain to audiences between songs the intricacies of the album’s plot, he snapped at the singer: “Fuck it, let’s play.”

Following another show in Paris, he and Alison were enjoying a candlelit meal in their hotel suite when Moon burst in. The over-refreshed drummer helped himself to Entwistle’s steak and a bottle of vintage claret, reeled around the room, relieved himself on the carpet and then left. “John was so angry that he followed Keith back to his room and smashed it up,” Alison Entwistle remembers.

Moon had passed out by then. When he came round the next morning and assumed he must have been responsible for the rampage, he meekly paid the bill for damages.

Entwistle worked right alongside Townshend on The Who’s next project, the soundtrack for Ken Russell’s overblown film adaptation of Tommy, but neither he nor Moon were required much on set.

“Dad always wanted to be on stage,” reflects Chris Entwistle. “That’s when he felt truly alive, and he lived for those times. He didn’t like the periods of inactivity. He loved to play and to show off.”

In 1978, flush from the tour that followed the release of The Who By Numbers, Entwistle made his most extravagant purchase when he bought Quarwood, a 55-room hunting lodge set in 40 acres of Cotswolds countryside. Intended as a weekend retreat, he set about furnishing it to his own particular taste. Suits of armour lined the corridors and many of the rooms, and in one a skeleton reclined on a Regency chair. In the cavernous kitchen were three bird cages filled with squawking parrots, and an effigy of Quasimodo hung from a bell rope in the hall.

“We went round the Cotswolds looking for houses together,” Alison Entwistle says. “John had wanted a country cottage, so you can see what I meant about him being reckless. Quarwood was a lovely house, but unmanageable at times. It was filled with his suits of armour. One was called Henry, and John used a fur hat of mine to pad out its helmet. I never did get it back.”

“I wouldn’t see dad in the mornings,” says Chris Entwistle. “He wouldn’t get up till midday because he’d have been in the studio or wherever, playing or rehearsing all night. On Sundays we used to sit together and watch old movies. He indoctrinated me with all the knights-in-armour films that he loved, classics like Ivanhoe and Black Shield Of Falworth. Those were the only times that I really spent with him when I was very young.”

Towards the end of 1977, The Who gathered again to work on what would be their eighth album, Who Are You. Entwistle contributed a trio of sturdy rockers, and the title track was a vintage Townshend anthem, but overall it was an uneven, unsatisfying record, due in no small part to the waywardness of Moon’s playing. Alcoholism had got the better of the band’s court jester, and he didn’t survive the next year.

On the evening of September 6, 1978, Moon and his new girlfriend, Swedish model Annette Walter-Lax, attended a party thrown by Paul McCartney. After arriving back at their rented flat in London’s Mayfair, Moon downed 32 pills of a medication prescribed to help him combat alcohol withdrawal, went to bed and never woke up. Entwistle was entertaining a group of journalists at Quarwood when Townshend called to tell him the shattering news.

“I had to go into the room and tell them: ‘Be gentle with him,’” says Alison Entwistle. “That was a very, very bad time for John.”

“Keith’s loss certainly hit John hard,” adds Bob Pridden. “John and Keith just clicked. They had a kind of telepathy between them, something that you couldn’t manufacture.”

Not long after Moon died, Entwistle’s marriage ended. The previous year he had spent six weeks out in Los Angeles working on the soundtrack to The Who documentary film The Kids Are Alright. During that time he had met and begun a relationship with Maxine Harlow, a 22-year-old waitress at the infamous Sunset Strip rock’n’roll hangout the Rainbow Bar & Grill.

“He came back home and I knew there was something wrong,” Alison Entwistle says. “So I asked him what was up. Pete had apparently told him: ‘Don’t ever tell Alison the truth,’ but he did. He said: ‘I’ve found someone else and I’m in love with both of you.’ I put up with it for eighteen months, until he made up his mind. It was the hardest thing I ever did.”

“Dad and I got to know each other better after he left, because he had to make time to see me,” says Chris Entwistle. “For the first year it was every Thursday night. We saw every movie that came out at the cinema that year. I also used to go and visit him at Quarwood at weekends.

“We had lots of chats. He told me once: ‘If someone tries to start a fight with you, put them down as fast and nastily as you possibly can and they won’t try again.’ That actually happened to me once, and they didn’t. When I was of an age, I would obviously talk to him about girls, and he would tell me about some of his experiences, which was an eye-opener, of course. He lived, I will say that.”

The Who soldiered on for four more years, with the dependable Kenney Jones, formerly of the Small Faces and the Faces, as Moon’s replacement, but they were a shadow of the band they had once been. Entwistle remixed 10 tracks from the original Quadrophenia album for the soundtrack to the passable film version of 1979, giving them new heft and sparkle.

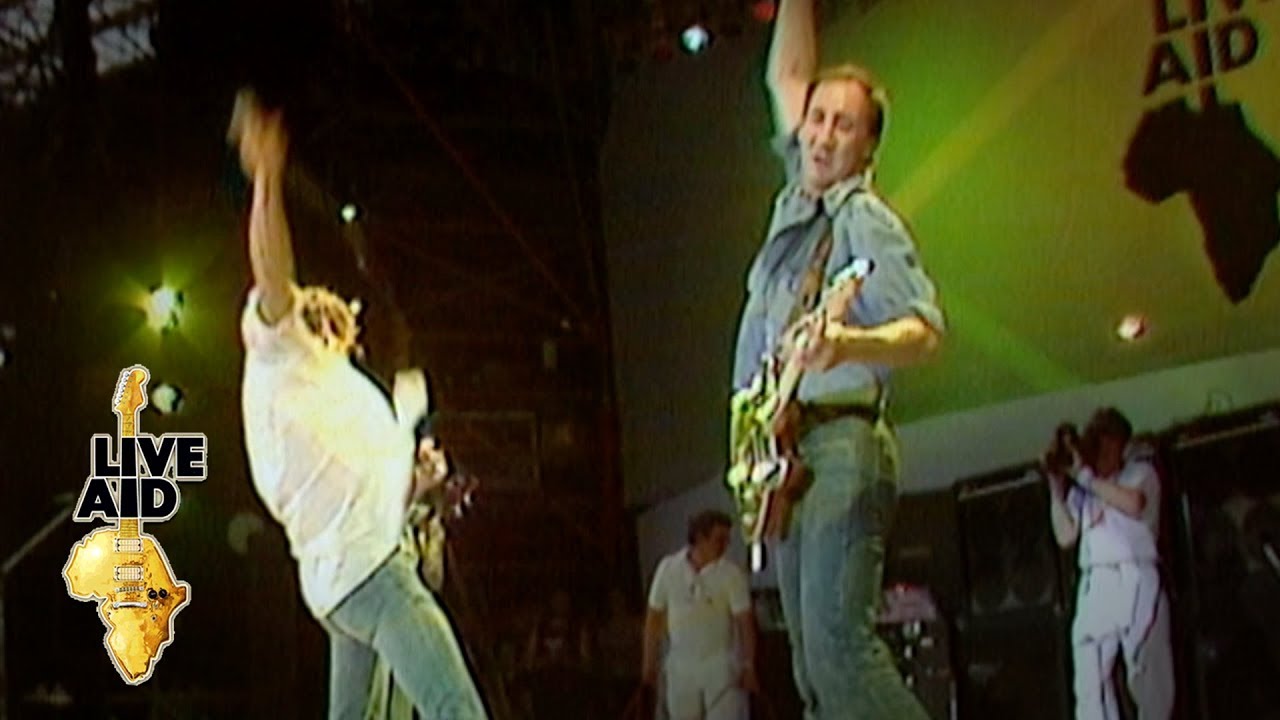

Neither of those qualities, however, applied to the last two studio albums he made with the band: 1981’s Face Dances and the following year’s It’s Hard. After the release of the latter, Townshend announced that he was retiring from touring with The Who, and the band was put to pasture for the next 14 years, save for a fleeting, glorious return at the Wembley Live Aid concert in 1985.

Entwistle occupied himself in other ways. His next solo record was the aptly titled The Rock, a stab at hard rock that remained unreleased for 10 years. He had a fleeting spell in short-lived supergroup The Best alongside Joe Walsh, Keith Emerson and Simon Phillips, a not-much-longer tenure in Ringo Starr’s All-Star Band, and toured his own John Entwistle Band.

In 1991, he and Maxine Harlow got married. From the start, theirs didn’t seem a union made to last. They were wed at a ‘quickie’ chapel in Las Vegas, with an Elvis impersonator as their witness. By the time they divorced, in 1997, The Who were resurrected.

The summer before, Townshend had invited Entwistle and Daltrey, plus drummer Zak Starkey and an expanded backing group, to join him for a performance of Quadrophenia in London’s Hyde Park. Tours of Europe and the US ensued. Two years later the band regrouped again, as a five-piece on this occasion, with Starkey once more and keyboard player John ‘Rabbit’ Bundrick completing the line-up. Townshend would claim later that the catalyst for this reunion was the parlous state of Entwistle’s finances.

He told Rolling Stone in 2015: “Roger came to see me and said: ‘Listen, I can’t see any other way that John can get himself out of the hole that he’s in. He’s spent too much [and] if you’re really the friend that you say you are, you should fucking help.’ And so I agreed.”

“Dad did care about the details,” counters Chris Entwistle, who went to work for his father in 1997. “His accountants used to ask him if he knew how much money he had got, and he would be able to give the figure to within a pound. He never saw any paperwork, but he kept a running total of things in his head. I just don’t believe that he sweated the small stuff.”

For the greater part of the last six years of his life, John Entwistle appeared to be thoroughly content with his lot. He entered into a new relationship with his friend Joe Walsh’s former girlfriend, Lisa Pritchett-Johnson. When not working he could often be found frequenting the pubs or pottering about the antique shops of Stow-on-the-Wold, a small market town close to Quarwood. He even paid for a new roof for the Stow Cricket Club pavilion.

Now, though, he was not the Ox of days gone by. His hearing was all but shot and he suffered from high blood pressure. His wan appearance at The Who’s show at the Albert Hall in February 2002 alarmed friends, but he passed a medical required for insurance purposes for the American tour lined up for that summer.

One Tuesday morning that June, Chris Entwistle drove his father to the airport to catch a flight to Las Vegas to begin that tour.

“I gave him a kiss goodbye, as I always did,” he recalls. “He turned around when he got to the door of the terminal, we waved to each other and that was the last time I saw him.”

John Entwistle spent the evening of June 27, 2002 with friends, among them Alyeen Rose, an exotic dancer he knew from previous visits to Vegas. He took Rose to his room at the Hard Rock Hotel, where he did a line of coke and they had sex. Some time during that night, he had a heart attack and died in his sleep.

“It turned out that one of his arteries was a hundred per cent blocked, and another seventy-five per cent,” reveals Chris Entwistle. “High blood pressure is a family trait. His mother had it, as do I, but we had no idea about the problems with his heart, and nor did he. We were told they would only have been found out with an electrocardiogram, which he never had because it hadn’t seemed necessary. He was very rarely ill.

“You know what, though? It wasn’t the worst way to go. It could have been a prolonged illness. One of the things I was most appreciative of, the doctor who performed the autopsy told me that he wouldn’t have felt a thing.”

John Entwistle’s funeral was held at St. Edward’s Church in Stow on July 10, 2002. In his will he split his estate equally between his mother, his son and Lisa Pritchett-Johnson. Pritchett-Johnson continued to live in a cottage on the Quarwood grounds after Entwistle’s passing, but had to move out when Chris Entwistle was forced to sell his father’s home to meet the crippling death duties.

“The Inland Revenue decided that everything dad owned had a value, including each item of clothing and his personalised car number plate,” he explains. “And they wanted forty per cent of it, thank you very much. The problem was that most of dad’s money was in stuff. For instance, over the years he had invested in a massive guitar collection, which was going to be worth a lot of money down the line, but that was a bad time to have to sell.”

Today, Alison Entwistle says that when she thinks back on her life with her late former husband, most often it is to the time their son was born. “John was so thrilled,” she says. “He was there when I gave birth at Queen Charlotte’s Hospital. I loved him for years and years, so you can never get rid of those feelings. He was a silly boy, but also very generous, warm-hearted and very, very talented."

“I would like dad to be remembered as the best bass guitarist that the world has ever known,” Chris Entwistle concludes. “That’s who he was, the guy that stood there and got on with the job.

“I haven’t seen Pete or Roger in God knows how many years now, because I won’t go to Who gigs any more. Not because of them – I’m firmly behind the boys carrying on as long as they want. I just can’t handle the fact that dad’s not there on his side of the stage, where he should be.”

Paul Rees been a professional writer and journalist for more than 20 years. He was Editor-in-Chief of the music magazines Q and Kerrang! for a total of 13 years and during that period interviewed everyone from Sir Paul McCartney, Madonna and Bruce Springsteen to Noel Gallagher, Adele and Take That. His work has also been published in the Sunday Times, the Telegraph, the Independent, the Evening Standard, the Sunday Express, Classic Rock, Outdoor Fitness, When Saturday Comes and a range of international periodicals.