“It was horrifying. The heat was intense and I felt at times that I was really burning”. The insane story of The Wicker Man, the folk horror cult-classic with a disastrous background

As The Wicker Man celebrates its 50th anniversary this year, we look at the making behind it and why it's such a masterpiece

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

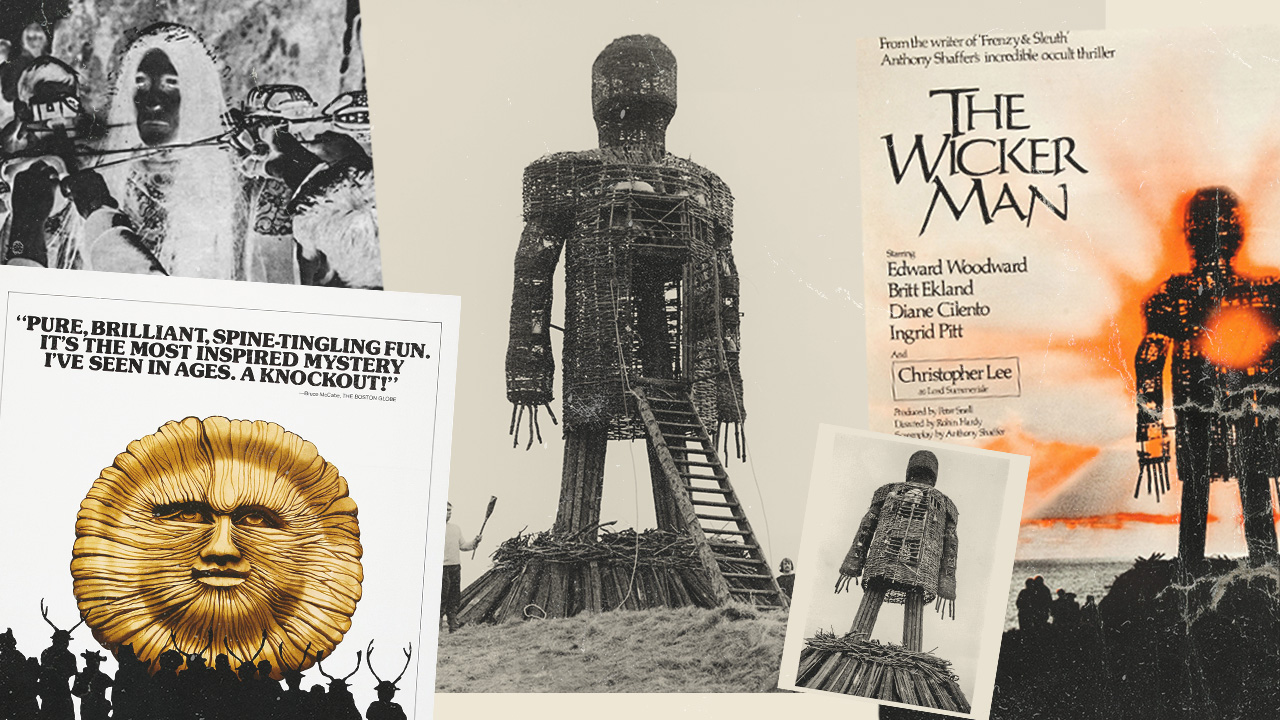

In 1973, a modestly-budgeted motion picture about human sacrifice and unfamiliar Pagan customs hit the big screen, reluctantly released by a studio who would have preferred the world to have disregarded its existence entirely. This year, that very film, Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man, celebrates its 50th anniversary, and remains not only unforgotten, but widely regarded as one of the greatest horror movies of all time.

Described by Cinefantastique magazine’s David Bartholomew as “the Citizen Kane of horror films”, The Wicker Man is pedestalled within British cinema as a pioneering blueprint within the genre of folk horror, its momentous impact parenting a trail of future projects, from Sky Atlantic’s pre-Christian series The Third Day and Ari Aster’s critically-acclaimed cult-centred horror Midsommar, to the 2006 box-office-flopping Wicker Man reimagining starring Nicolas Cage. Alton Towers even homes its own tribute, a ride named after the film’s title, crafted wholly out of wood.

Written by Anthony Shaffer, the cult classic was largely inspired by David Pinner’s 1967 horror novel Ritual, and follows the disarming journey of Sergeant Neil Howie - a puritan Christian (played by Edward Woodward) who embarks to the fictional Scottish island of Summerisle in search of a missing girl. Upon his arrival, he discovers the area to be inhabited by merrymaking heathens who have abandoned their Christianity in exchange for public copulation, pagan practices and - befalling Howie’s own demise - human sacrifice.

At this point, cinema had never before born witness to such a disquieting depiction of Paganism; its eerily earthy eccentricisms stripping humanity back to its oldest of ways, marked by the overt sexual symbolism of seasonal celebrations and hedonistic free-spiritedness. The Summerisle townspeople, unbound by the constraints of a modern society ruled by law, order and the familiarity of monotheism, shape the nightmarish plot with a game-like trickery, culminating in the shocking final scene of the burning of the sacrifice-bearing wooden monolith, presented as an offering to appease their sun god, Nuada.

Otherworldly and marvellously disorientating, its legacy may be airtight, but The Wicker Man was surprisingly conceived from less rewarding beginnings, following numerous inner squabbles, a meagre budget, lost edits, issues with its set and an unhappy cast. Most problematically, upon its release, the film was stifled by its own studio, British Lion, who on believing it to be “rubbish and undistributable”, limited the film’s launch with no official press screening. Instead, it was shuffled out off the back of Nicholas Roeg’s psychological thriller Don’t Look Now in an unlikely double-billed screening, only capturing the attention of film critics through the desperate cheerleading of Christopher Lee (starring as Lord Summerisle), who called reviewers himself, offering to pay for their seats out of his own pocket. In the summer of 1975, he even self-funded a trip to America to publicise the US release.

In fact, on top of being the film’s one-man publicity team, Hammer Horror icon Lee, whose role as Lord Summerisle was written specifically for him, sacrificed his entire pay check, and offered to work on the project for free, correctly believing his inclusion within the project would bolster interest. Speaking in the 2001 documentary The Wicker Man Enigma, the actor said: “I got paid nothing. I keep repeating to people and they don’t believe it’s true. I’ve got the contract to prove it. Anyway, sometimes you do things for love…If they paid me my normal fee - and everyone else their normal fees - they wouldn’t have been able to make the film”.

On top of its rocky distribution, The Wicker Man’s editing process was an additional cause of frustration. To the dismay of Lee, British Lion’s execs believed the film too long, and slashed out some of his favourite scenes. In his memoir, Lord Of Misrule, he lamented: “Cuts are unavoidable, but some of these seemed like amateur butchery, it wasn’t merely that I had some good lines shaved off, but entire parts, excellently played, had gone”. Other moments were apparently lost in 1974 after numerous film reels were swallowed by a landfill, buried underneath a newly-built road on the M3 motorway, near to British Lion’s HQ at Shepperton Studios in Surrey, England. “I don't know whether instructions were given to destroy it, or to hold it somewhere under another name”, theorised Lee in an interview with The Telegraph. Due to the finicky approach to editing, over the years, four different versions of the film have been created, ranging from 87 to a rumoured 102 minutes long.

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

Shooting The Wicker Man proved testing, too. As Ingrid Pitt (who’s credited simply as the Librarian) declared in The Wicker Man Enigma, “ever since the film got started in script form, there was a nightmare over it like a black cloud”.

Despite being set during the May Day celebrations of Spring, it was shot throughout October and November across the damp and cold moors of Scotland; the art direction team even had to mimic apple trees in bloom using plastic. Due to the low temperatures, Pitt revealed that she used her knees to keep Woodward's toes warm, telling him, "Don't worry, they're going to burn you in a minute!". And when it finally came to setting the wicker man itself alight, Woodward was far from comfortable surrounded by so much heat. "I've done an awful lot of things in the years since that picture was made”, he explained, “but never, ever have I been so frightened as when I was in the wicker man itself. It was horrifying. The heat was intense and I felt at times that I was really burning." To make matters worse, a goat - one of the 'live sacrifices' - was so frightened by the flames it pissed on Woodward’s head.

Britt Ekland, who starred as Willow MacGregor, the landlord’s daughter, additionally claimed that the work environment was marred by “ill-feeling”, noting: "People were not really nice to each other. It was every man for himself.” She also took issue with the fact her nude posterior was body-doubled by a Glaswegian stripper, and that her dialogue was fully dubbed over by Scottish singer Annie Ross.

Regardless of The Wicker Man’s many initial setbacks, the film rose from the ashes into a certified cult-classic, venerated for its use of atmosphere over bloodiness, striking visuals, ebullient costume, its reverence for the uncanny side of British history (Morris dancing, harvest-ensuring rituals), and an ambient, psychedelic-edged soundtrack, helmed by musical director Gary Carpenter and written by Paul Giovanni. There’s curiously enchanting folk ditties (Corn Rigs), tongue-in-cheek pub songs (The Landlord’s Daughter) and children’s nursery rhymes (Maypole), frequently sung and performed in an almost mesmerising, ritualistic fashion, potent in heady magic.

Aesthetics aside, one of the greatest facets of The Wicker Man is the casting of Christopher Lee; the role he was questioned about most until he starred in Peter Jackson’s The Lord Of The Rings as the wizard Saruman. A household name in horror, Lee’s sonorous bellow commanded an unearthly resonance like that of a God booming incantations down from the heavens, a spellbinding delivery perfectly matched to his role as Summerisle's stately cult leader.

Half a century later, and The Wicker Man is still etched inside cinema's collective mind: from Woodward's face of panic upon seeing the sacrificial vessel for the first time (what we see on screen really is the actor's first time seeing it), the fire-leaping maidens singing the unsettling fertility hymn Fire Leap from within the stone circle, to the startling presence of the Hand Of Glory left beside Howie's bed, the film is a trove of arresting scenes that leave hairs on end.

Disastrous beginnings it may have had, but The Wicker Man is irremovable from the modern cinematic landscape of today, and a masterpiece that will undoubtedly live on for years to come.

Liz manages Louder's social media channels and works on keeping the sites up to date with the latest news from the world of rock and metal. Prior to joining Louder as a full time staff writer, she completed a Diploma with the National Council for the Training of Journalists and received a First Class Honours Degree in Popular Music Journalism. She enjoys writing about anything from neo-glam rock to stoner, doom and progressive metal, and loves celebrating women in music.