I tried to do a review of The National and ended up writing the worst thing you can write...

...some weird old-guy waffle about what-it-were-like-in-our-day, plus stuff about The Pogues, gig etiquette, Poptimism, and why classic rock will grow old but won't grow up.

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

We are standing in Prospect Park in Brooklyn, taking the piss out of The National for all the things they are not.

“It’s not Honky Tonk Women, is it?” says my companion, a song or two in.

The live show has some giant screens which occasionally show distorted, pixellated images of artsy abstract-y stuff. “It’s not exactly Kiss,” I say.

And so on. You can imagine.

They play The Geese Of Beverley Road (as song titles go, it's not exactly Too Drunk To Fuck) one of the few songs I recognise and actually love. It has this doomed-romantic us-against-the-world feel, with a lyric about being young and hungry, running through the streets, burning with mad ambition.

“We'll run like we're awesome, totally genius,” sings Matt Berninger. “Hey, love, we'll get away with it/We’ll run like we're awesome/We’re the heirs to the glimmering world…”

At times The National are the indie E-Street Band, with a back catalogue full of evocative, widescreen epics.

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

They are The Mmmm Street band. The Uh Street Band. And, sometimes, they are The Zzz Street Band.

“Oh, come, come be my waitress and serve me tonight,” sings Berninger at the end of the song. “Serve me the sky with a big slice of lemon.”

It gets the biggest cheer of the night.

“And the crowd goes mild!” says my wise-cracking friend.

The Meek Ain’t Gonna Inherit Shit

We’re here because we both like The National’s music but I'm telling him about the last time I saw them. It was London in 2006 and it put me off the band for years. (I should stress: I tell him this quickly – we’re not having a conversation, there’s nothing much to say, the gig in 2006 was so forgettable.)

We’re standing in the crowd near the sound desk. A guy in front turns and leans towards me.

“I’m having trouble hearing,” he says.

I have no idea what he means. Is that a song title?

“I’m sorry?” I say.

“I’m having trouble,” he says, “hearing.”

I’ve been talking. He’s trying to ask me to be quiet without actually asking.

His friend turns to give him some moral support. “When the song’s on…” he says.

This could also be the name of a song by The National.

“C’mon,” I shrug. “It’s a social occasion.”

They both look at me like I just shat in their soya lattes.

Now I have have read comments like this online – “I didn’t pay for a ticket to listen to you talking!” – so I sympathise and I realise that this might mean that you and I can never be friends but…

Seriously? Fuck. That.

This is not an acoustic show in a small club. We’re standing in a park in Brooklyn, NYC, surrounded by 1000s of people, watching a live rock band. It’s hardly the right place to demand silence.

And if you really want to be ‘the heirs to this glimmering world’? You might have to dig a little deeper.

Anyway. Like I was saying before I was so rudely interrupted:

The last time I saw The National was in 2006 and it put me off them for years.

It was a weird time. I had just become the Editor In Chief of Classic Rock magazine. It was a big life change. I’d moved towns. Went from working in Bath to working in London and I had three kids under the age of three.

I’d grown up listening to all sorts of stuff – punk, alternative, goth, psychobilly, classic rock, hip-hop, techno, ambient – but for Classic Rock I threw myself into rock, devouring all the stuff I already loved (Thin Lizzy, AC/DC, Motorhead, Zeppelin, Hendrix and the Stones), and discovering bands and artists from the 70s I’d never really listened to before (Frankie Miller, Terry Reid, Blue Oyster Cult, Bob Seger, Grand Funk, Cactus, Santana, UFO etc etc). I was a classic rock convert, a rabid rock evangelist.

But at the same time, I wanted Classic Rock to cover new bands.

My taste in rock music wasn’t frozen in the 70s. The National’s Alligator had been one of my favourite albums of 2005. It was mournful, impressionistic, confessional. It was literate like Leonard Cohen, romantic like The Blue Nile – but at the same time they sounded like a band you might have caught them supporting The Chameleons or The Sound in the mid-80s.

You could argue that their music connected to Roxy Music’s art rock, to Bowie’s Berlin period, that there was a fairly straight line that ran from Pink Floyd to them (think Nobody Home, say, from The Wall), via post-punk, shoegaze and genuine progressive prog, which held a similar fascination with textures, atmospherics, modernity and so on.

The National’s influences spanned 30-40 years of enduring rock music.

But I soon realised that most Classic Rock readers didn’t want that, really. They wanted bands whose influences spanned an even mightier range: 1968-73.

They were happy for rock music to grow old but they didn't want it to grow up.

A Self-Indulgent Aside About Old School Gig Etiquette

The fourth or fifth gig I ever went to was The Pogues at Glasgow Barrowlands, in December 1985. It was an 18+ gig, but this was Glasgow in the 80s. I was 14 and my mate Billy would have been 15 and we’d already managed to sneak in to see Echo & The Bunnymen, Siouxsie and The Banshees and The Cult there.

But nothing prepared us for The Pogues. Their hell-raising Celtic folk-punk struck a chord with the Glasgow audience. It was a riot. We bumped into some older kids from our school and during the gig they grabbed me and Billy and swung us around in a mad highland jig – and then let us go.

The Barrowlands’ floor was wet with rain and spilled lager and we both went flying across it, sliding into people’s legs and ending up in a heap a few feet from the front. We picked ourselves up, laughing, and pogoed into the middle as plastic glasses full of lager sailed over our heads – and occasionally bounced off them, soaking us.

When the gig was over and we spilled out on the December Glasgow streets, we were so hot and wet, clouds of steam billowed off us as soon as we hit the cold air. We looked like we’d been on fire – like Wile E Coyote after his wheelbarrow full of dynamite has exploded – and we felt like it too.

That’s a gig. If your live music experience is being ruined by someone talking, or holding up their phone to film a few second’s worth of video, then you might not be cut out for this rock’n’roll lark.

Everything I can remember about the first time I saw The National

I took a mate to see The National at Koko in Camden in 2006. I still thought of them as a small band that only I knew about – but the gig was sold out.

I can’t remember much about it except that I was bored. There was no performance, as such. The band looked like students: young and awkward and underachieving. The poetry of the record was lost. I genuinely couldn't bring myself to listen to another National album until this year.

(My memories of the Koko gig are so sketchy now that I just texted my mate Fin to see if he remembered anything. “I can remember the band were slick and the lead singer’s voice was bourbon smooth!” he texted back. “Does that help? It was a very long time ago. I had hair 😂”)

Mumblers Vs Hollerers

There was no way Classic Rock’s audience would accept The National. For loads of reasons but mainly:

One: Matt Berninger’s voice. The National’s singer is a Mumbler. He makes Lou Reed sound like Whitney Houston. Classic Rock readers preferred Hollerers: red-blooded, big-voiced blerks who could belt out a tune.

Two: The music. I’m saying: Cohen/Roxy/Bowie/Floyd etc. They’re hearing: indie.

Because, Three: Classic Rock readers were tired of being told by music critics that all the music they loved was naff, stupid, crass, cheesy and unfashionable. They’d had years of being told that their music was crap compared to the critically acclaimed young flavours-of-the-month and as a result they had, quite reasonably, decided that music magazines (your NMEs, Qs, Mojos) were run by cloth-eared clowns.

Classic Rock magazine was an escape from all that.

My favourite song by The National

My favourite song by The National is called All The Wine. Like many of the band’s songs, it’s hard to say for sure what it’s about but I’m guessing it’s about a guy who’s had “all the wine” and is, therefore, feeling pretty fuckin’ gallus.

“I'm a perfect piece of ass,” he sings, “like every Californian/ So tall I take over the street/ With high beams shining on my back/ A wingspan unbelievable/ I’m a festival, I'm a parade/ And all the wine is all for me.”

Later, continuing this mad metaphor of being some kind of giant blocking the streets of NYC, he sings: “I'm so sorry but the motorcade will have to go around me this time.” I love that.

When I told Classic Rock’s Dave Everley I was trying to write a review of The National but it was coming out all weird he screwed his nose up: “Aw man,” he said, “that guy has some of the worst lyrics I ever heard.”

Sometimes I think it's impossible for anybody to agree on anything anymore.

It's impossible for anybody to agree on anything anymore

Somewhat ironically, around this time something else happened that would see The National grouped-in with exactly the same old rock bands Classic Rock magazine did cover.

In October 2004, exactly the same month that I joined Classic Rock, the New York Times published a piece by Kelefa Sanneh called The Rap Against Rockism. In it, he wrote rock’s obituary, slating both rock bands and rock critics.

Those old fellas’d had their way for too damn long, he said. Old white men had sung the praises of other old white men for decades, and in the process had created a racist, sexist and homophobic boys’ club. And their time was up.

“Rockism means idolizing the authentic old legend (or underground hero) while mocking the latest pop star,” he wrote, “lionizing punk while barely tolerating disco; loving the live show and hating the music video; extolling the growling performer while hating the lip-syncher.”

I’d love to say that Sanneh’s piece informed my decade as Editor In Chief of Classic Rock. But it didn’t, because I didn’t read it. In fact, I didn’t even hear about it until last year.

But I felt it.

The old media empires crumbled over the next 10 years. Sanneh’s article gave rise to what has been called ‘Poptimism’. Rising new online brands started to take ‘pop acts’ as seriously as music mags had once taken rock. Newspapers sent columnists to eulogise shows by Beyonce and Katy Perry. It was a revolution!

(It wasn't. Anyone who remembered Julie Burchill's The Modern Review – "Low culture for high brows" – or grew up reading the likes of Steven Wells in UK music press was used to this. The new wave was just less funny and more self-congratulatory.)

The old rock legends continued to be sneered at as coffin-dodgers and paedos, while bands like The National were attacked for the very things the music press used to love about them: because they were smart, worthy, authentic. They could – spit! – play their instruments and write their own songs, like that mattered!

But mostly because they were that most unfashionable of things: white males with guitars.

“The National makes me feel that rock music, like much of American literature and visual art before it, has died and gone to graduate school,” wrote Carl Wilson in a review for Slate. “The band delivers certifiable Quality-with-a-capital-Q, a perfect product of the English and music departments—the way that Lady Gaga is a perfect product of the semiotics department and an MBA program, though I definitely prefer Lady Gaga.

“At my most extreme, I’d even claim that The National reflects the way social and economic stratification are narrowing the space for cultural free agency and rewarding artists who straightforwardly serve either the libido of the mass market or the neurotic narcissism of the privileged classes.”

Er, yeah. Like, that’s what I was gonna say. That’s the Voice Of The People right there!

(The Poptimists will probably hate this, but Poptimism has much in common with the political populism that has brought us Trump and Brexit, in that it argues that an educated, elitist class has been telling us what to do/how to live/who to love for decades – and now it’s “our” turn. It's the revenge of the masses. In this case, Revenge On The Nerds.

And actually, it fits the 'rock narrative' quite nicely. Queen, Elton, Motley Crue have something in common – for much of their careers, despite enormous popular success, they were mocked by the likes of Rolling Stone and NME. Now the shoe’s on the other foot, fucko. Now, they drive clicks. And that’s really all that matters.)

A public service announcement

The live pictures on this page are of The National at Prospect Park, Brooklyn, but they were taken at their 2014 gig, and are here purely for illustrative purposes.

It looked kind of the same, honest. It looked just like that and it smelled of weed.

An Aside That’s Actually A Proper Live Review Written By A Die-Hard The National Fan

Guitar World's Jackson Maxwell went to see The National the night after me. It rained, but Jackson is in his 20s and they’re his favourite band. I asked him to write his thoughts so you’d get a different perspective. This is what he wrote:

Having seen The National twice before—once at this same venue—the set I watched them play was an interesting spectacle. Less a rock band workshopping its discography than a large ensemble trying both a new album (the sprawling ‘I Am Easy to Find,’ which comprised almost half the night’s setlist) and an entirely new approach to music on for size, it was a two-hour exhibition of a band known for little but air-tight sonic consistency stretching their legs as they never have before.

Fascinatingly, the environment scrambled the impact of a sizeable chunk of the new album’s songs—the stately grandeur of “Light Years” diluted by a hometown crowd made restless and excitable by a relentless summer downpour, “Not in Kansas,” meandering and insecure in its six verses on record, fed off its audience, ending on the communal, cathartic note of a hymnal.

What hadn’t changed though, was the immediacy and breadth of the band’s back catalog. Oughts-era album tracks “Apartment Story” and “All the Wine,” their arrangements having morphed some over the years, were mid-set flexes, a seasoned band in its backyard winking at the die-hards (like this one) who have taken such fierce ownership of certain corners of their discography.

Like ‘I Am Easy to Find’ itself, The National’s Thursday night set at Prospect Park wasn’t without its missteps—the occasional moments of messiness and missed connections—but it largely showed a band still head and shoulders above any of their NYC early-oughts indie contemporaries, and much more willing to fly close to the sun than most people give them credit for.

He can write, that Jackson. And he's right: The National of 2019 are a much more convincing proposition that the one from 2006. Seeing The National live didn’t put me off listening to them this time around. In fact, listened to their new album, I Am Easy To Find, over and over. Try it. There are a load of female guest vocalists and that adds a richness and warmth lacking in some of their other work. It also has some of the greatest drumming I’ve heard this year. (I recommend the opening track, You Had Your Soul With You, and The Pull Of You - if you don’t like those, forget it.)

The bit that tries to be an ending

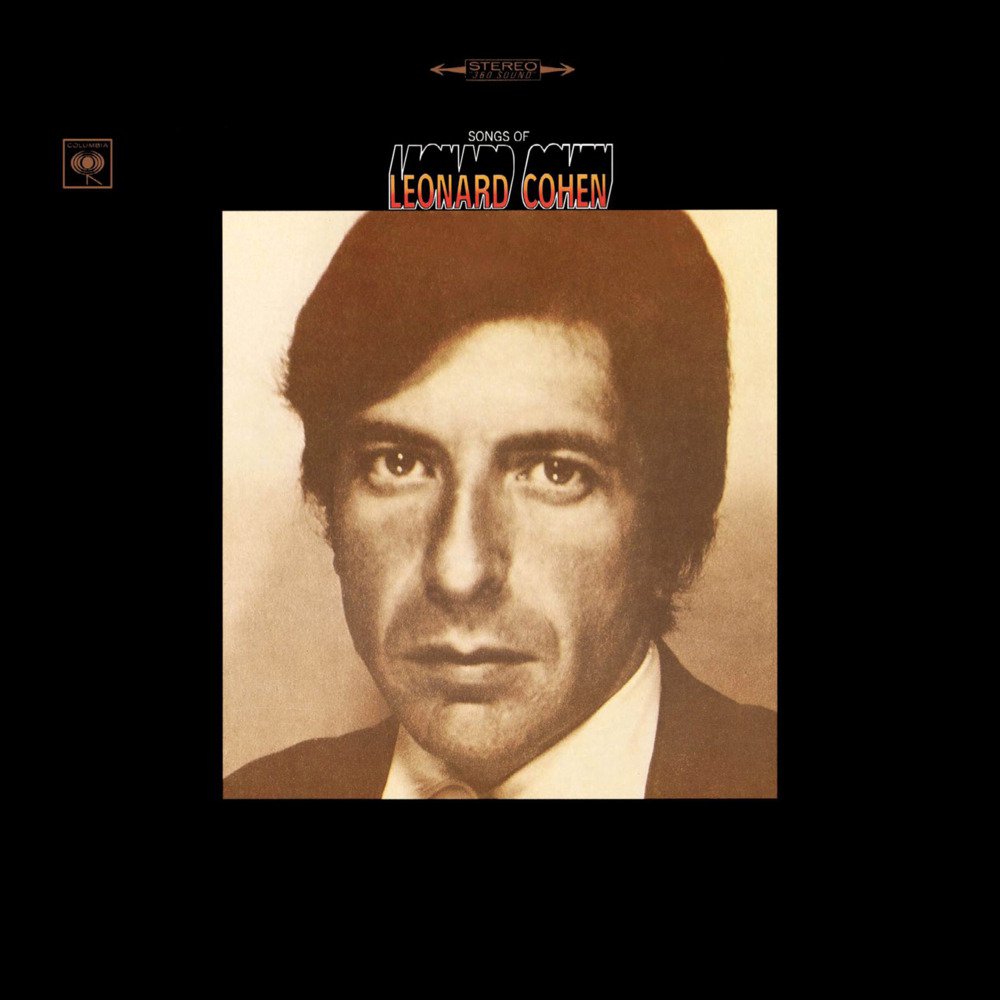

When I was maybe 16 or 17, I stayed over at my sister’s house. Her boyfriend had a great record collection and we were going through it, playing Iggy Pop, Lou Reed, Mott The Hoople – anything Bowie-related. I was flicking through the records when I came across a compilation called Songs Of Leonard Cohen.

“What’s he like?” I said. “I’ve heard he’s supposed to be good.”

“He is,” said The Boyfriend. “But I tell you what: don’t put it on now. Wait til we’ve gone to bed and then listen to it on the headphones.”

So I did. I slept in the living room. I plugged in the headphones, put the needle to the record, switched the lights off and listened to those fingerpicked nylon strings and that voice: ‘Suzanne takes you down to her place near the river/You can hear the boats go by, you can spend the night forever…’

It was magic. And he was right. If we’d played it after Raw Power, it would’ve sounded lame.

Maybe there’s a place for all kinds of music. Maybe not all music is going to work in every situation. Maybe this whole piece has been about tolerance. Maybe it's just more self-indulgent old man waffle.

And maybe, just maybe, The National are a band I don't need to go and see live again. Maybe they're a lights-off-headphones-on kinda band.

The National's new album, I Am Easy To Find, is out now. The band are touring internationally from June this year.

Scott is the Content Director of Music at Future plc, responsible for the editorial strategy of online and print brands like Louder, Classic Rock, Metal Hammer, Prog, Guitarist, Guitar World, Guitar Player, Total Guitar etc. He was Editor in Chief of Classic Rock magazine for 10 years and Editor of Total Guitar for 4 years and has contributed to The Big Issue, Esquire and more. Scott wrote chapters for two of legendary sleeve designer Storm Thorgerson's books (For The Love Of Vinyl, 2009, and Gathering Storm, 2015). He regularly appears on Classic Rock’s podcast, The 20 Million Club, and was the writer/researcher on 2017’s Mick Ronson documentary Beside Bowie.