How Pink Floyd reinvented themselves and journeyed towards The Dark Side

After Syd Barrett left, Pink Floyd were on a constant search for a sound – their sound. Eventually, Roger Waters, David Gilmour, Rick Wright and Nick Mason would find it

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

In Pink Floyd’s long and illustrious history, Cyril Van Den Hemel’s name is a footnote at best. Yet in 1968 he had the rare distinction of booking Britain’s premier art-rock band to play matinee gigs in Dutch primary schools. “To eight-year-olds, sitting cross-legged on the floor, wondering what the hell was going on,” remembered Floyd’s former bass player Roger Waters.

Van Den Hemel ran the Europop Agency, who booked the cream of underground bands, such as Floyd, Deep Purple and Jethro Tull, to play Amsterdam’s hippie nightspots The Paradiso and Fantasio.

In early summer 1968, Van Den Hemel booked Pink Floyd for a tour of the Netherlands and Belgium. Their hit single See Emily Play and whimsical debut LP The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn had accompanied the previous year’s so-called Summer Of Love. But by the end of 1967 Floyd’s talismanic frontman Syd Barrett was on his way out.

Waters, keyboard player Rick Wright and drummer Nick Mason replaced Barrett with guitarist David Gilmour. But their future looked uncertain. Pink Floyd began 1968 grateful for any work, which is how Van Den Hemel persuaded them to play in schools. These clandestine performances took place in the afternoon before a regular show, and without the knowledge of the band’s management.

“Cyril would say: ‘You only need to bring the drum kit and one amp,’” said Waters. “He’d then wheel us into the school auditorium.” Nobody involved can remember what Floyd played, only the baffled expressions on the faces of their junior audience These gigs lasted as long as it took Van Den Hemel to extract their fee in guilders, and rarely more than 15 minutes: “He’d say: ‘We got the money! We go now!’”

This was the band’s cue to throw their instruments in the van and high-tail it away like bank robbers fleeing a heist. A few hours later they’d be on-stage somewhere like the Concertgebouw in the Dutch harbour town of Vlissengen, blowing stoned young minds with songs like Astronomy Domine and Interstellar Overdrive. Business as usual.

In 1973, Pink Floyd’s eighth studio album The Dark Side Of The Moon made them one of the biggest bands in the world. But back when they wheel-spun their van out of school carparks in Holland, global stardom seemed unlikely. Pink Floyd were still working out what sort of group they were going to be.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

This journey of self-discovery would involve film soundtracks, performance art happenings, a man dressed as a monster urinating on the audience, a woman named Constance Ladell with a radioactive pacemaker….

The new Pink Floyd began when David Gilmour first plugged in his Strat in their rehearsal room and played like Jimi Hendrix. Gilmour had grown up in Cambridge with Waters and Barrett, but didn’t mimic Barrett’s abstract guitar style. He’d become a semi-pro musician at 15 – and it showed.

“It was a relief having him in the band,” said Mason. “Though at first we had this idea we’d be a five-piece – David would do the heavy lifting and Syd would stay at home and write songs.” But this proved impractical when Barrett failed to deliver any songs. His behaviour had become increasingly erratic, due to undiagnosed mental health issues and his use of hallucinogenic drugs.

For a time, the two guitarists shared stages together. But it was problematic. One roadie recalled a gig where a disorientated Barrett stood so close to Gilmour that he was an inch from his face: “Syd then started walking around, almost checking if he was a three-dimensional object.”

Gilmour insists he can’t remember which band member suggested not picking up Barrett for a gig at Southampton University in January 1968. But that snap decision made in the back of a car would have a profound impact on their lives.

On April 6 it was officially announced Syd Barrett had left Pink Floyd. The following week the band released a new single, It Would Be So Nice, a Kinks-ish pop ditty, with keyboard player Rick Wright singing lead vocals. It tanked. “Complete trash,” Waters said later.

The band returned to Abbey Road studios to lick their wounds and complete their second album. They’d started it with Barrett, but it was Waters who drove A Saucerful Of Secrets over the finishing line. He was the least experienced musician (and Wright never tired of telling interviewers how he had to tune Roger’s bass), but Waters had previously worked in an architect’s office, and was scared of going back.

“I just hated being under the boot so much,” he said in 1970. “And I can always build a house for myself one day if I want to.”

Waters took the bit between his teeth and almost willed himself to become a songwriter. But both he and Floyd’s other principal writer, Rick Wright, had to find a new direction.

“We could never write like Syd,” cautioned Wright. “We never had the imagination to come up with some of the lyrics he did.”

The tracks that defined A Saucerful Of Secrets were the ones that sounded the least like the old Pink Floyd: Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun and the title track were mini-symphonies with prolonged instrumental passages; a dummy run, of sorts, for what would come later with Echoes and Shine On You Crazy Diamond.

Pink Floyd launched the A Saucerful Of Secrets album on June 29, 1968, at the Midsummer High Weekend, a free festival in London’s Hyde Park. Hippie elves Tyrannosaurus Rex and earnest folkie Roy Harper warmed up the audience before the Floyd unveiled their new epic. The festival’s compere, DJ John Peel, listened to A Saucerful Of Secrets stoned, in a boat on the Serpentine in the park.

“The sounds fell around our bodies with the touch of velvet and the taste of honey,” he enthused in Disc magazine – with which he scored a mention in Private Eye’s Pseud’s Corner column a week later. Pink Floyd were delighted.

“After Syd left, a lot of people thought we were over,” said Mason. “Hyde Park made us feel like we were still relevant, still part of something.”

Their appearance on Belgian TV show Tienerklanken from this time captures a group in artistic limbo, though. They mime a game of cricket to See Emily Play: Waters uses his bass as a bat, Mason bowls an invisible ball, Gilmour tries to catch it; and Wright looks like the world’s feyest wicketkeeper. Waters, at least, appears committed to the charade, marching around the pitch with a rictus grin on his face and ‘firing’ his bass like a machine-gun. He looks determined to make it work, whatever it is.

Waters was similarly committed on stage. While his bandmates peered through curtains of hair and pondered their fashionable Gohill boots, Waters prowled like a caged tiger, wringing the neck of his Rickenbacker bass, and gleefully whacking a gong during Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun.

Unfortunately, Floyd’s next single, the Sgt Pepper-ish Point Me At The Sky, again failed to make the UK Top 40. Nick Mason recently performed this song with his touring group Nick Mason’s Saucerful Of Secrets.

“I never imagined I’d be playing it live again, no,” he said in 2020. “Its lack of success convinced us we should stop aiming for the Hit Parade and concentrate on making albums. Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun and A Saucerful Of Secrets showed the direction we should be going in. But we got rather distracted after that.”

There were several distractions. Early in 1968, Waters claimed Pink Floyd were planning shows in a circus-style big top along with jugglers and escapologists. They’d also applied for a £5,000 grant from the Arts Council to fund a rock opera.

“It would be written as a saga, like Homer’s The Iliad,” Waters told Melody Maker. “I’d like Arthur Brown to play The Demon King, with the Floyd providing the music.”

Neither idea came to fruition, but both demonstrated Waters’s desire to explore other mediums. In 1967 Pink Floyd had created a collage of electronic bleeps for conceptual artist John Latham’s movie Speak. That was followed a few months later by some abstract drones for director Peter Sykes’s film-noir The Committee.

Nick Mason told me they’d also pitched to write the music for Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: “I suspect it fell down not only because Pink Floyd weren’t necessarily right for it, but also because the deal would have been so poor.”

Outer space had become a theme, though. In July 1969, Floyd provided what David Gilmour called “spacey twelve-bar blues” to accompany the BBC’s live broadcast of the first Moon landing.

It was a commission for another film, French director Barbet Schroeder’s earthbound More, that became their next album.

“I was a big fan of the first two Floyd records,” Schroeder told me in 2006. “I thought they were the most extraordinary things I’d ever heard, and I wanted to work with them.”

Schroeder flew to London with a copy of his film: a story of drug taking and thrill seeking in Ibiza, and containing a copious amount of artistic nudity. He convinced Pink Floyd to write the soundtrack (for the princely sum of £600 each), but with one caveat.

“Barbet didn’t want a soundtrack to go behind the movie,” Waters said. “He wanted it literally. So if a radio was switched on in a car, he wanted the music to come out of the car. He wanted it to relate to exactly what was happening in the movie.”

More was recorded in a nine-day marathon at London’s Pye studios in early ’69, and released in August. “A lot of the moods in the film were ideally suited to some of the rumblings, squeaks and sound textures we produced on a regular basis,” suggested Mason.

Perhaps surprisingly, More’s curious hybrid of pop, jazz, electronica and even heavy metal made the Top 10. Crucially, songs such as the sweetly melodic Cymbaline and Green Is The Colour pushed David Gilmour’s voice to the fore.

“Doing film music was a path we thought we could follow in the future,” said Gilmour. “It wasn’t that we wanted to stop being a rock’n’roll band, it was more of an exercise.”

The band’s record label, EMI, had indulged them so far, but after More “EMI thought we should cut out all the weird nonsense and get on with it”.

This proved easier said than done. Floyd’s experimentation was a cornerstone of their live show. As preferred venues for many bands, the Mecca and Top Rank ballrooms of 1966 and ’67 had been replaced by university halls and underground clubs, whose woolly-haired, Afghan-coated patrons wanted sounds that transported them beyond the Top 40. Pink Floyd fitted the bill – and then some.

The band had composed two new conceptual works, The Man and The Journey, to illustrate a day in the life of an average man. “Sleep, work, play, start again,” Waters explained, unwittingly prefacing themes explored later on The Dark Side Of The Moon.

Both pieces were played live that summer, and utilised sound effects, elements of theatre and performance art. At London’s Royal Festival Hall, a baffled audience watched a 20-minute sequence titled Work in which Pink Floyd constructed a table on stage. When it was complete, a roadie boiled a kettle and served the band tea.

“The idea was that the sawing and the hammering created a rhythm. It was interesting and fun and meant to provoke, but I don’t think we were being great artists. There was an awful lot of floundering around,” Gilmour admitted.

Sometimes, the performance extended beyond the stage, into the audience. During The Final Lunacy show at London’s Royal Albert Hall, one of Floyd’s art school friends dressed up in a ghoulish latex costume, nicknamed The Tar Monster. He then dashed down the aisles spraying fake urine from a plastic phallus. “One unfortunate girl screamed and rushed from the auditorium,” recalled Mason.

Yet beneath the art-school humour were musical ideas signposting the way ahead. The sound of the roadie’s boiling kettle was later used in 1970’s Atom Heart Mother album, and ringing alarm clocks from one section of The Journey made a reappearance on The Dark Side Of The Moon.

Capturing this live experimentation on record was difficult, though. The Man and The Journey were cast aside, and for Pink Floyd’s next album Waters suggested each band member compose a solo piece. Waters managed two. One of them, Several Species Of Small Furry Animal Gathered Together In A Cave And Grooving With A Pict, was a headache-inducing collage of ‘found’ sounds and Waters babbling in a fake Scottish accent. It encapsulated the fly-by-night nature of the project; none of the band members heard each other’s contributions until they were complete.

The two studio sides were then packaged with two sides of live recordings, and Pink Floyd’s first double album, Ummagumma, was released in November 1969. The title came from Floyd sometime roadie Iain ‘Imo’ Moore, notorious for his lexicon of slang and Tourette’s-like swearing.

“It was one of my sayings,” Imo told me. “‘Ummagumma’ means ‘I’m-a-gonna…’ as in ‘ummagumma go home and, er, shag my girlfriend…’”

Today the band sound unconvinced by the album. “Ummagumma was interesting,” allowed Mason, whose studio contribution The Grand Vizier’s Garden Party included a protracted drum solo and his ex-wife Lindy playing flute. “But Roger suggesting we write our own individual pieces felt like being back at school and told to write an essay.”

“We were very good at jamming,” said Gilmour, “but we couldn’t quite translate that on record.”

However, Ummagumma reached No.3, their highest chart placing yet, and, despite its “weird nonsense”, strengthened the band’s position at EMI. Floyd had become the stars of EMI’s hip new imprint Harvest Records (ahead of Deep Purple, the Edgar Broughton Band and Kevin Ayers), and officially Britain’s biggest underground band.

Buoyed by a sense of freedom, they spent the next few months getting distracted again. In 1966, Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni had been fêted for his ‘Swinging London’ movie Blow-Up. Three years on, Antonioni hoped to repeat its success with Zabriskie Point, a muddled tale of student radicals in California, and asked Pink Floyd to write the music. Floyd checked into Rome’s palatial Hotel Massimo in November, with Antonioni footing the bill. Their work ethic was relaxed.

“Every day we’d get up at about four-thirty in the afternoon,” Waters told music magazine Zigzag. “We’d pop into the bar, and sit there until seven. Then we’d stagger into the restaurant, where we’d eat for two hours and drink…”

At 9pm the band dragged themselves to the studio, where they’d work until the morning. There were elements of The Man and The Journey in this approach: “Sleep, work, play, start again…” etc. But Antonioni was unimpressed by their efforts.

“It was always wrong, consistently,” Waters complained. “There was always something that stopped it being perfect. You’d change whatever was wrong, and he’d still be unhappy.”

The band and director parted company. Only three Floyd songs made the finished soundtrack, which was bumped up with music from the Grateful Dead and The Youngbloods. But nothing was wasted. A melancholy piano piece titled Violent Sequence that was rejected by Antonioni was later repurposed for Dark Side’s Us And Them. “We were now following a band policy of never throwing anything way,” explained Mason.

Smarting from Antonioni’s rejection, Pink Floyd went back on the road. Their stock had risen since their last American tour, when they could get gigs only at weekends and were marooned in cheap motels for days on end.

Finding ways to fill downtime on tour proved difficult. Having had a ringside seat for Syd Barrett’s LSD-fuelled decline, they now generally stuck to dope or Scotch. Waters had taken his second, and presumably last, acid trip in New York. He’d only gone out to buy a sandwich, but was overwhelmed by a sudden, inexplicable fear while crossing Manhattan’s Eight Avenue: “I ended up stood there, frozen and unable to move.”

In future, Waters amused himself by setting his travelling companions a challenge and placing bets on the outcome. For one, roadie Chris Adamson (the first voice heard on Dark Side, saying: “I’ve been mad for fucking years…”) agreed to eat a stone (6.35kg in today’s money) of raw potatoes. “To give him his due, he got through two-and-half pounds before he said, ‘Fuck it,’” recalled Waters.

Around the same time, Gilmour took up a challenge and rode a motorcycle through a hotel restaurant in Scottsdale, Phoenix. “Funnily enough, it didn’t get any reaction at all,” he said. “People were so frightened by it that they all stared very hard at their plates.”

In April 1970, though, when the band began their latest US tour, it was all about the sensory overload of the music and the show. They headlined New York’s underground hotspot Fillmore East, followed by shows at Philadelphia’s equally hip Electric Factory and on to San Francisco’s Fillmore West. The Great Speckled Bird, an underground newspaper in Atlanta, enthused about Floyd’s “merging of electronics and psychedelics… rhythmic birdcalls and giant stereo footsteps that echo around the hall”.

“We got good reviews everywhere,” Mason told Melody Maker. “All the audiences said they’d never seen anything like us before.” During these dates they road-tested a new 23-minute instrumental, which would acquire several working titles – The Amazing Pudding, Untitled Epic and Theme From An Imaginary Western – in the weeks ahead. Floyd had already recorded the backing track at Abbey Road. But fleshing it out proved difficult.

“We added, subtracted and multiplied the elements,” said Mason. “But it lacked an essential something.”

They decided the missing ‘something’ was a choir and orchestra. But none of the group knew how to write a score. Fortuitously, Waters had struck up a friendship with Scottish musician and poet Ron Geesin, a veritable one-man band, whose tastes encompassed jazz, classical and avant-garde, but, as he told me, less so “Pink Floyd’s astral wanderings”.

Geesin agreed to score Floyd’s new work, but claimed the band had only a vague idea of what they wanted: “Dave [Gilmour] talked to me about the theme, and Rick went through a few phrases for the vocal section.”

When Floyd returned from America, Geesin handed them the score as a fait accompli. Days later he was at Abbey Road attempting to explain it to the EMI Pops Orchestra. “I was a novice, really,” he admitted later. “I was not a conductor.”

There were already issues. Due to EMI’s restrictions on splicing expensive one-inch recording tape, Mason andWaters had been forced to record the backing track in one wobbly take. “It lacked metronomic timekeeping,” confessed the drummer.

The piece also included some technically challenging parts and difficult phrasing. Most of EMI’s Pops Orchestra were hard-bitten classical players with little time for upstart rock groups. Ron Geesin was almost five years older than Pink Floyd, but the orchestra had him pegged as another useless hippie. “Ron waved his baton hopefully, and they made as much trouble as they could,” recalled Mason.

When Geesin threatened to punch one of the brass players, it was suggested he take the rest of the day off. His replacement, John Alldis, was an experienced conductor who kept the orchestra in line, and used his own choir to supply wordless vocals. The end result was a 23 minute, 41 second concerto, fusing ghostly voices and booming brass with Gilmour’s trademark string-bending guitar solos.

With one half of the LP in the can, the band created four pieces for the second side, “from scraps of things they had lying around”, said Geesin. Once again they worked individually. Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast, composed mostly by Nick Mason, was a flashback to The Man and The Journey, with the sound of roadie Alan Styles frying eggs and bacon, boiling a kettle and rhapsodising about “toast, marmalade, cereal…”

The album was completed by July, but still lacked a title. Waters was backstage before a Floyd gig at London’s Paris Theatre, discussing the problem, when Ron Geesin gave him a copy of the day’s London newspaper the Evening Standard for inspiration. Waters leafed through the pages desultorily before spotting a story about Constance Ladell, a 56-year-old woman who was the first person to be fitted with a radioactive plutonium pacemaker. The headline read: ‘Atom Heart Mother Named’.

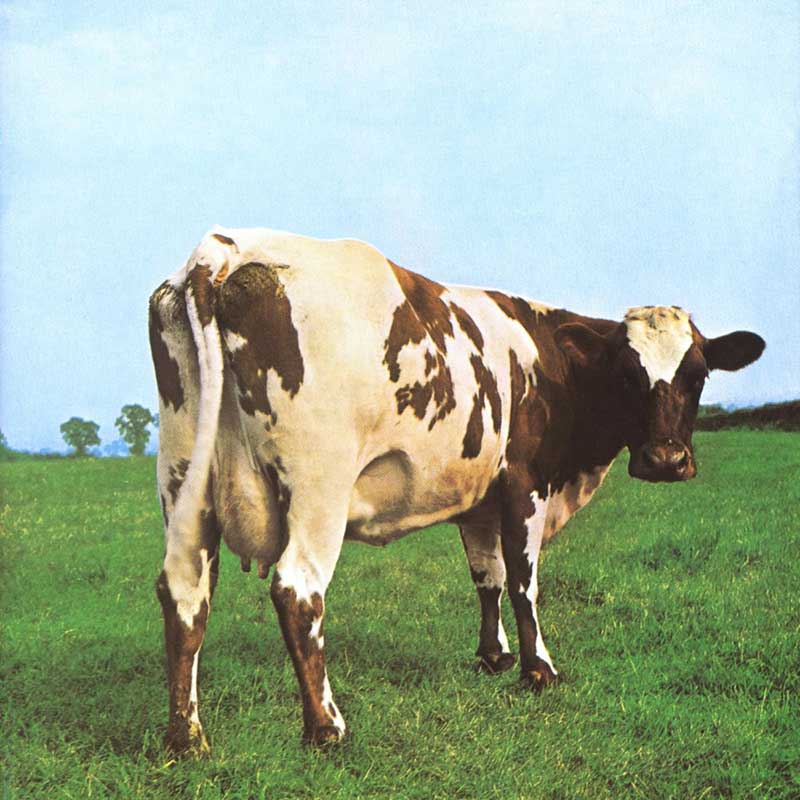

Atom Heart Mother bore no relevance to the music, but it gave Floyd’s problematic concerto and album a title. They had already commissioned their friends Storm Thorgerson and Aubrey ‘Po’ Powell, of design collective Hipgnosis, to create a cover for the album. Thorgerson and Waters were old schoolfriends and similarly single-minded and outspoken.

This wilful streak led to Hipgnosis photographing a baleful-looking Friesian cow in a field for the cover, and insisting that neither the band’s name nor the title was to be on it. Floyd loved the contrariness and absurdity of the concept. Even more so after a senior EMI executive saw the cow and screamed: “Are you mad? Do you want to destroy this company?”

Pink Floyd might have been at loggerheads with their paymasters, but their audience listened merrily to Alan frying his breakfast in glorious stereo, and pondered the mystical meaning of “the cow… man”, just as they’d done the nonsensical title ‘Ummagumma’.

Released in October 1970, Atom Heart Mother, the album that some had feared would destroy EMI, went to No.1 in the UK. Pink Floyd were always their own fiercest critics, though. At times both Gilmour and Waters have been brutally dismissive of this period in their shared history.

“Absolute crap,” was Waters’s blunt verdict on Atom Heart Mother’s title track. Placed alongside the later Time or Shine On You Crazy Diamond it comes up wanting. But, like Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun and those deeply buried treasures on More, it was a stepping stone towards The Dark Side Of The Moon and Wish You Were Here. There would be no Time or Shine On You Crazy Diamond without them.

Sometimes those outside a band help those inside to examine their past work with fresh eyes. In 2018, former Blockheads guitarist Lee Harris and Roger Waters’s bass-playing successor Guy Pratt asked Nick Mason if he would consider forming a band to play Pink Floyd’s early material. But neither expected him to say yes.

Soon after, Nick Mason’s Saucerful Of Secrets (completed by former Orb keyboard player Dom Beken and Spandau Ballet guitarist/vocalist Gary Kemp) were performing Atom Heart Mother, Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun and other Floyd relics at venues around the UK. Pre-COVID, the band were about to commence the sold-out Echoes Tour in April 2020.

The tour’s name was taken from a lengthy composition, on 1971’s Meddle, that defined the pre-Dark Side Floyd more than any other. By the time the band started work on Meddle, they’d realised that their greatest strength was their collective songwriting. What Mason called “the rumblings, squeaks and sound textures” had been a subconscious way of disguising the fact that they couldn’t compose pop songs like Barrett.

But Pink Floyd had arrived at a new sound. Barbet Schroeder believes that working under duress on the soundtrack album More taught Floyd a valuable lesson. “I do think it surprised Pink Floyd that they could make such a good album in two weeks,” he said. “Perhaps they shouldn’t have taken so long in the studio on all their other records.”

The songs on Meddle were never hurried or forced, and the writing and performances were more streamlined, be it the ominous One Of These Days, or sleepy lullaby A Pillow Of Winds. Echoes, arguably the key composition on Meddle, took up the whole of the second side, and was testament to Floyd’s experience and chemistry.

Gilmour had now established his place in the band. He was both a brilliant interpreter of Waters’ big ideas, and an immovable force if those ideas threatened the music. It was this artistic tug-of-war that made Echoes so compelling. Its shifting moods and movements deployed eerie sound effects and experimentation. But at its beating heart was a simple melody and Gilmour and Rick Wright’s combined lead vocals.

Equally important, the lyrics explored what Roger Waters now called “inner space”; human emotions and real life, instead of “airy-fairy mystical bollocks”. Its inspiration came from Waters’ early time in London and that strange, uncertain period immediately after Syd Barrett’s departure.

Waters was living in a flat in Shepherd’s Bush. Every morning, he watched a stream of commuters heading, like worker ants, towards the Tube station; every evening, he’d watch them all come back again. It was a bleak reminder of the working life he might have had if Pink Floyd hadn’t survived the loss of Barrett and he’d had to become an architect.

“The lyrics are all about making connections with other people,” he explained. “About the potential that human beings have for recognising each other’s humanity.” This included making a vital connection with the rest of Pink Floyd.

“Meddle was the first album we had worked on together as a band since A Saucerful Of Secrets, three years earlier,” said Mason. “We finally realised what we were good at and what we should be doing.”

“It would become a template for everything else after,” added David Gilmour. “Atom Heart Mother felt like the end of something, and this felt the beginning of something else.”

By 1971, the second stage of Pink Floyd’s long, strange trip had reached its destination. The next stop was The Dark Side Of The Moon, and there would be no turning back.

Mark Blake is a music journalist and author. His work has appeared in The Times and The Daily Telegraph, and the magazines Q, Mojo, Classic Rock, Music Week and Prog. He is the author of Pigs Might Fly: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd, Is This the Real Life: The Untold Story of Queen, Magnifico! The A–Z Of Queen, Peter Grant, The Story Of Rock's Greatest Manager and Pretend You're in a War: The Who & The Sixties.