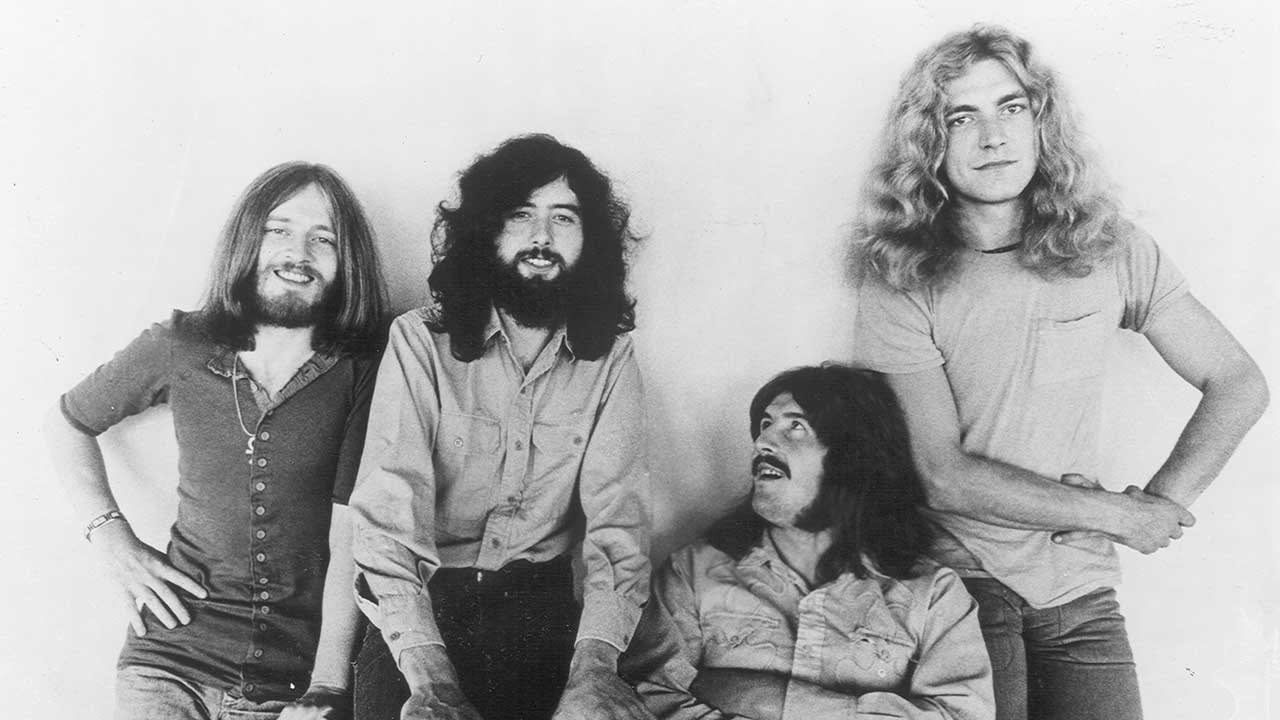

How Led Zeppelin rewrote rock’s rulebook and changed the music business

Led Zeppelin did business like no one before, especially when it came to dealing with their record company. Former Atlantic Records Vice-President Phil Carson explains all

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

It wasn’t just the sound of rock music that Led Zeppelin changed forever. The music business was never the same again either. The contract that Zeppelin signed with Atlantic Records in late 1968 included not just the biggest advance ever handed to a new group at that time, it also gave them unprecedented control over every aspect of their music and image.

What made the deal even more remarkable was that nobody at Atlantic had seen Led Zeppelin play live before they signed them. In fact the band had only played a handful of gigs, and most of those were as The New Yardbirds. But Atlantic had heard the tapes of the first Led Zeppelin album.

“It was [producer] Jerry Wexler who wanted to sign them. He’d recognised the enormous talent of Jimmy Page,” says Phil Carson, who was in charge of running Atlantic Records’ international operation at that time and later became a vice-president of the company. “It was then handed over to [Atlantic’s founder] Ahmet Ertegün who finalised the deal with [Zeppelin manager] Peter Grant.”

Carson continues: “The deal changed the way things were done because Led Zeppelin demanded a massive measure of control. They controlled what singles would be taken from an album, they controlled the artwork. They controlled the mastering process – Jimmy Page mastered every album personally. Atlantic had absolutely no say in any of that stuff whatsoever.”

How were Led Zeppelin able to do this?

"Because it was clear to Ahmet immediately what he was dealing with – the talent of the band and the talent of the management team. Peter was running the thing with the assistance of [leading New York music business attorney] Steve Weiss. And Ahmet realised there was something extraordinary in the way that Peter Grant and Jimmy Page had created Led Zeppelin.

"He knew it would be the very best. He also knew that The Yardbirds, the band Jimmy had been with previously, had a following in the States so they would be able to tour even though they had no record out when the first tour was booked. Jimmy already had a reputation as an artist, even though it was fairly low-key. No one knew any of the others, but the impact was instant.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Why did Led Zeppelin approach Atlantic?

“The fact that Atlantic had been so successful with Cream probably had something to do with it. Plus I think Jimmy had a respect for the music coming out of Atlantic. The catalogue of music that Ahmet and Jerry had built up there was hugely respected among British musicians. And Atlantic still had the air of an independent label even though it was a pretty big company by then. It certainly wasn’t a corporate record company.

"They also had this edict about signing bands – ‘Only sign a band if there is a virtuoso musician in it.’ Because virtuoso musicians don’t play with good musicians, they only play with excellent musicians. And if you think about Led Zeppelin there are four virtuoso musicians in that band."

Led Zeppelin could veto singles, but they couldn’t control what radio played, could they?

“Jimmy’s whole idea was that you should play an album in its entirety. In those days I would go into a radio station like [pioneering New York station] NWEW with Jimmy and [DJ] Scott Murray would put on side one of Led Zeppelin II and play the whole fucking thing. Other DJs would pick up on different tracks. Sometimes there would be a consensus and then the record company would go to the band and say: ‘Hey, we’ve gotta put that track out as a single.’

“That’s how Whole Lotta Love came to be Zeppelin’s first big single. It was edited to bring it down to a reasonable length, which caused all kinds of mayhem. In the end they agreed that the edited version could be played on radio but not sold in the shops. My first experience with Peter Grant was over Whole Lotta Love when I decided to put it out as a single in England.

"I had it pressed and ready to go out, when I was summoned to Peter Grant’s office and told: ‘You can’t do that.’ I said: ‘What do you mean? I’m running the record label over here.’ And he said: ‘You speak to Ahmet right now.’ So I rang him from Peter’s office and he said: ‘Get the damn thing back.’ I did it but about 1200 copies leaked from our Manchester distribution centre, and now they’re huge collector’s items. I just wish I’d kept a few.”

Didn’t this deprive you of a publicity tool?

“That’s what we all thought. But we were proved wrong because any airplay simply made people search out the album. After a while you wondered whether rock bands really needed singles. And in Zeppelin’s case they certainly didn’t.”

Other bands, like ELP and Yes, released singles. Even The Rolling Stones.

“The Stones were always a singles band. They never really sold a lot of albums until they joined Atlantic. It was just the concept of marketing that Atlantic had was different. Which is one of the reasons the Stones signed with Ahmet.”

Why did Led Zeppelin refuse to go on TV?

“They did a few right at the beginning but they were not happy with how they sounded on television. They felt that if you wanted to see the band you should go to a concert. By the middle of 1970, a year and a half after they’d signed to Atlantic, they’d already done five tours of America, and found time to record their second album. It was incredible.”

So what was Atlantic’s role?

“More or less innocent bystanders! All we had to do was keep our heads down and make sure the records were in the stores. We also got the radio play, but we had nothing to do with the live side of things. Zeppelin concert tickets would go on sale without advertisement. Sometimes it was just announced on a radio station. It was mostly word of mouth. The interesting thing is that it still is, only now it’s the internet generation. So you had 1.2 million people applying for 16,000 tickets to see them at the concert they did for Ahmet in 2007."

Hugh Fielder has been writing about music for 50 years. Actually 61 if you include the essay he wrote about the Rolling Stones in exchange for taking time off school to see them at the Ipswich Gaumont in 1964. He was news editor of Sounds magazine from 1975 to 1992 and editor of Tower Records Top magazine from 1992 to 2001. Since then he has been freelance. He has interviewed the great, the good and the not so good and written books about some of them. His favourite possession is a piece of columnar basalt he brought back from Iceland.