How Black Sabbath ditched the hippy dream and faced brutal reality on Paranoid

With themes of war, madness and nuclear holocaust, Black Sabbath’s Paranoid remains the ultimate difficult second album. Fifty years on, we remember how it razed the rock’n’roll landscape

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Summer 1970, and paranoia is in the air. In less than a year, Woodstock’s vision of a kinder society has turned to ashes. The carnations placed in rifle barrels by Vietnam protesters have not slowed the shipment of body bags. The Cold War’s adversaries edge closer to their nuclear buttons. Meanwhile, amid the craters, rubble and roaming gangs of Birmingham’s Blitz-scarred Aston, the members of Black Sabbath are feeling the spirit of the age.

“I was scared stiff that we’d be dragged into Vietnam, and World War Three seemed a very real event,” Sabbath’s bassist and lyricist Geezer Butler says, a half-century later. “I was really into flower power in the sixties. I went to the love-ins at Woburn Abbey in sixty-seven and sixty-eight, with kaftan, beads, and flowers in my hair. But by the time we wrote the Paranoid album reality had set in. A lot of my lyrics were my disappointment that the love era was just a pipe dream. The love-ins and protests were all in vain.”

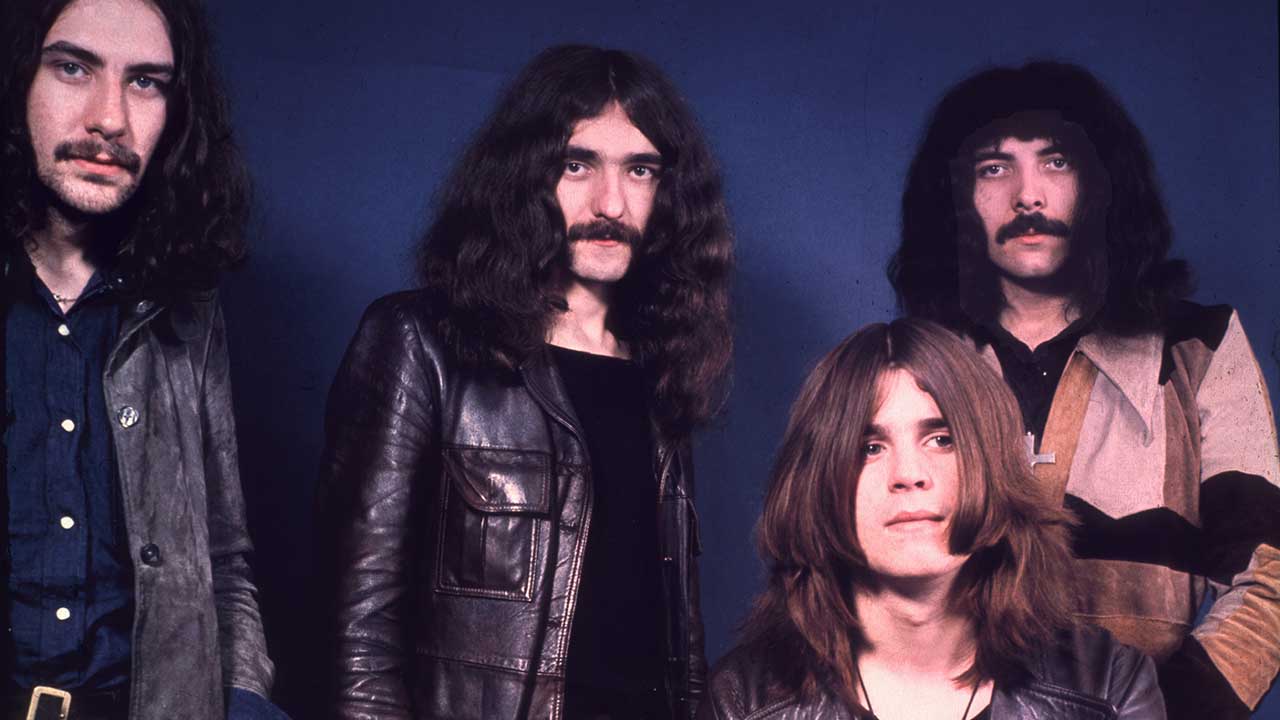

Sabbath had already put a little distance between themselves and reality. Despite the best efforts of a snide rock press and an apathetic record industry, the band’s self-titled debut album had been a transatlantic success, reaching No.8 in the UK and No.23 in the US. But with media daggers drawn and the threat of conscription on the cards – or, even worse, a return to the abattoirs and welding factories they’d just escaped – Butler, guitarist Tony Iommi, drummer Bill Ward and singer Ozzy Osbourne were still running as hard as they could.

Article continues belowThe genesis of the material that hardened into Sabbath’s thundering second album, Paranoid, is a slippery subject. Ward believes that some songs date back to ’68. Osbourne talks of reel-to-reel tape recorders spinning for hours at marathon jam sessions, hoovering up countless wisps of gold. Butler recalls the debut album’s live show-stopper, Warning, bleeding into War Pigs at thinly attended early shows.

“There would be about three people in the audience,” Iommi told Rolling Stone. “So we’d just make things up.”

Origins, perhaps, were less important than originality. “The first album was signed on the strength of Evil Woman, a cover song, and Warning was a cover song as well,” says Butler.

“Success gave us confidence in our writing. It meant we could go ahead and write all original material for Paranoid. The critics were brutal on our first album, so when it was successful it showed they were way out of touch with what was happening. With Paranoid, we only had ourselves to please. If we liked the songs, that was all we needed.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Working the live circuit across Europe, while snatching days for writing sessions, the band finally came to rest at Rockfield Studios in Wales, where pre-production with trusted producer Rodger Bain literally blew the roof off.

“There was an old barn where we set up,” Butler recalls, “but when we started playing, part of the roof fell in because of the volume. We were four kids from Aston, just glad to be living our dream. We still lived in Brum with our parents at the time, so any chance to travel out of the inner city, we gladly took. It was sort of a paid holiday for us – we were very close, us against the world sort of thing. We loved having a laugh, getting stoned and drunk together.”

Archive shots of Sabbath larking with air rifles on the riverbank suggest a Boy’s Own adventure, yet Rockfield’s rural idyll was far from the dystopian track-listing now taking form. These were songs that found the band with one eye on darkening global politics, another examining their own mental states, with a healthy stir of sci-fi and the occult. As Iommi told music paper Disc & Music Echo: “We write about what’s happening in the world. We prick consciences.”

Fascinatingly, the just-released Paranoid Super Deluxe box set includes an unreleased performance from Montreux, showing how album opener War Pigs might have sounded had it continued with its original title of Walpurgis and Butler’s witchy lyric (‘On the hill the church in ruin, is the scene ofevil doings/It’s a place for all bad sinners, watch them eating dead rats’ innards’).

In its final form, the song was less schlocky, more thoughtful, with Butler’s second draft attacking the capitalist war machine that sent soldiers to the meat grinder and enriched the politicos, with Iommi stabbing a brutal riff after each line.

While War Pigs put the stench of burning bodies into listeners’ nostrils, Hand Of Doom’s bleakly groovy jazz-rock explored battle’s fallout, drawing on the band’s experiences of playing US military bases in England, where soldiers numbed their post-traumatic stress disorder with narcotics.

“Hand Of Doom was about people on drugs and what happens to them, their skin turning green and things,” Osbourne told NME. “There’s a lot of gory words, but we’ve seen a lot of people like that and it’s getting out of all proportion. If you can frighten people with words, it’s better than letting them find out by trying drugs. [But] I’m not trying to say that we’re angels.”

Electric Funeral repeated Hand Of Doom’s tempo trick of kicking from a funereal trudge into fifth gear, this time with Iommi working a wah-wah pedal while Osbourne caterwauled about a nuclear holocaust that ‘turns people into clay/Radiation minds decay’.

Positively hippie-ish by comparison, Butler believes the woozy swoon of the “interplanetary love song” Planet Caravan was the result of a heavy session on the band’s preferred black Afghani hash. But any sniff of benevolence was snuffed out by the closing Fairies Wear Boots, a nod to the night when skinheads hijacked a gig in Weston-superMare and got more than they bargained for.

“One grabbed Ozzy around the neck and didn’t realise he had a hammer,” Iommi recalled. “He threw the hammer back and hit the claw in the guy’s face. It was quite gruesome.”

When it came to recording at London’s Regent Sound and Island Studios, from June 16, 1970, Bain proved adept at stretching the basic four- and eight-track technology. Not every idea flew – Iommi recalls two wasted hours chanting “heigh-ho”, from Disney’s Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs. But by cloaking Osbourne’s introductory vocal with a ring modulator effect, Iron Man truly sounded like the song’s character: a steel soothsayer scorned for warning humanity of its bleak future.

“Iron Man was the result of a jam,” says Butler. “The song was based on the story of Jesus Christ – a hero at one point, then reviled a few months later.” Ward’s Rat Salad was little more than a cut-and-shut of his live drum solos, and Paranoid’s talismanic title track didn’t take much longer, spat out in the final moments of a five-day session, after Bain announced the album’s running-time fell short.

While Iommi’s deathless riff was pure impulse, Butler didn’t have to look far for his lyric about a man blighted by mental health: the bassist had taken to self-harming after doctors advised him to drink away his depression.

“I couldn’t understand what was happening to me,” he explains. “So I wrote the Paranoid lyrics to express what I was going through. I thought the song was too commercial-sounding compared to the rest of the album. Probably why I wrote the ‘downer’ lyrics. How wrong I was!”

Decades later Osbourne would complain that “I’ve never been on a stage without singing fucking Paranoid”. Yet without the chain of events set in motion by the single reaching No.4 in the UK, Sabbath might never have ruled the 70s. To capitalise, the album title was swiftly changed from War Pigs to Paranoid, rendering the artwork nonsensical as well as ugly (Butler: “I hated the album sleeve”).

While the press response to the album was reliably savage, Paranoid made it to No.12 in the US, selling more than four million copies there.

On home turf, Sabbath’s ascent was even more striking, with Paranoid topping the UK album chart (their only record to do so until 2013’s 13), sending the band members on a triumphant drinking bender, not to mention a spending spree that saw them swanning around the Black Country in newly acquired Rolls-Royces.

“It was brilliant,” says Butler. “After all the criticisms and doubters, our fans showed who the most important people are. We were able to buy cars, move out of our parents’ houses, have some money in the bank.”

Paranoid’s success came at a price, though. The band were bemused to find their shows infiltrated by teenyboppers who had bought the Paranoid single.

“It happened a couple of weeks back at a gig in Portsmouth,” Osbourne grumbled in Disc & Music Echo at the time. “We opened with Paranoid as usual, and suddenly the place went potty. There were kids rushing down the front, girls screaming and grabbing at us. We don’t need fans like those, but we’ll just have to grin and bear them and they’ll go away.”

More troubling were the misinterpretations of the album’s intentions, with critics accusing the band of Satanism, advocating drugs and driving listeners to suicide (a situation exacerbated when a nurse killed herself with Paranoid spinning on her record player, even though the band were cleared of blame at an inquest).

“A lot of people have a grudge against us because this black magic thing, but it’s got out of all proportion,” Ozzy told the NME. “I believe in black magic, but I haven’t tried it and I won’t.”

In the past, Butler has said that such smears “severely pissed me off”, railing in particular against the mis-hearings of the final line of Paranoid’s, in which Osbourne tells listeners to enjoy – not end – their lives. Fifty years later, it seems, his conscience is clear. “I didn’t care how people interpreted the album. The only people I cared about were our true fans. The people who misinterpreted the band didn’t even listen to us. Their interpretations were directly opposite of what the band was about.”

Cast an eye across the rock’n’roll generations since 1970, however, and it’s clear that all the people who matter were listening hard to Paranoid. The album is rightly considered a stone-cold cornerstone of metal, touching everyone from Van Halen (who almost named themselves Rat Salad) to Megadeth (who covered the title track) to Pantera (who, improbably, took Planet Caravan for a spin).

As Rob Halford of Judas Priest points out in the Super Deluxe sleeve-notes: “Paranoid led the world into a new sound and scene.” True, but the record’s influence runs deeper and wider, too, cited by acts as disparate as Foo Fighters, Faith No More and The Replacements.

“Paranoid still stands up today,” says Butler. “Because it was recorded ‘raw’; there aren’t any gimmicks or tricks that date the album. There wasn’t much room for double-tracking and multiple takes… If we’d had longer in the studio, the songs would have suffered from overproduction. I think most heavy bands of today cite Paranoid as a major influence. Iron Man is a fun riff to learn when you get your first guitar. At my granddaughter’s school in California it’s a staple in their music class – her teacher didn’t believe her when she said her grandpa was in Black Sabbath.”

Running parallel with that acclaim, of course, is the tragedy that Paranoid remains as grimly relevant as ever. War, mental health, the risk of a beating from far-right skinheads… The subjects explored across the album’s eight tracks are both of their time and eternally prescient, chiming with any given zeitgeist.

“Substitute any Vietnam reference with any current war and the lyrics still stand up,” Butler concludes “Mental health issues are finally being talked about in the media. Electric Funeral still applies as far as pollution and the destruction of Mother Earth is concerned. I think the lyrics to Paranoid are timeless.”

Black Sabbath's Paranoid Super Deluxe edition is available now via BMG.

Henry Yates has been a freelance journalist since 2002 and written about music for titles including The Guardian, The Telegraph, NME, Classic Rock, Guitarist, Total Guitar and Metal Hammer. He is the author of Walter Trout's official biography, Rescued From Reality, a music pundit on Times Radio and BBC TV, and an interviewer who has spoken to Brian May, Jimmy Page, Ozzy Osbourne, Ronnie Wood, Dave Grohl, Marilyn Manson, Kiefer Sutherland and many more.