Feel The Noize: the tragic and triumphant rise of glam revivalists Giuda

Putting a reinvigorating modern spin on a style of music that was all about simply having fun, Giuda are, as glam-rock connoisseur Joe Elliott puts it, “making this totally unfashionable music fashionable again”

Archive listing from TV Times magazine, June 5, 1972:

BBC1: Top Of The Pops

7.30pm, Colour

Tony Blackburn and Ed ‘Stewpot’ Stewart are joined in the BBC TV Centre studios by The Sweet, Suzi Quatro, Status Quo, David Bowie, Jo Jo Gunne, Pan’s People and, from Rome, Italy, brand new hitmakers Giuda, who will be playing their in-with-a-bullet Top 3 single Racey Roller. Theme music: CCS

Bristol, England, 2020. Up a steep set of stairs at the side of a pub on a busy road on the outskirts of the city centre, we come across five men who have spent the last half hour tirelessly lugging their equipment from a van down there to an empty room up here.

The boozer is local institution The Louisiana, and together the men make up Italian bovver-rock bootboys Giuda. In a few hours’ time this empty room will be packed with a couple of hundred people of all shapes, sizes, ages and hairstyles, here to see a bunch of ex-punk rockers who hold the past and future of a long-discarded musical movement in their hands.

Giuda (Italian for ‘Judas’)– play rock’n’roll like it used to be played. More specifically, they play rock’n’roll like it used to be played in the clubs and on the TV sets of the United Kingdom during a halcyon period that stretched roughly from the start of 1971 to the spring of 1974 – from T. Rex’s Hot Love to Sparks’ This Town Ain’t Big Enough For The Both Of Us, basically.

The band have been held up as modern figureheads of a semi-mythical movement dubbed ‘junkshop glam’. Joe Elliott, Def Leppard singer and glam-rock connoisseur, loves them.

“They crack me up,” he says. “Nobody does that any more. They’re making this totally unfashionable music fashionable again.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

That’s not wrong, but it’s not the full picture either. Giuda are no Butlin’s-style retro-revue tribute band, no Showaddywaddy in stack heels. Born on the back of tragedy, they’re simultaneously an immaculate homage to rock’n’roll’s most unsung period, and the single most life-affirming thing you can experience right now.

They’re fighting the good fight to the soundtrack of a ballroom blitz. As guitarist Lorenzo Moretti puts it: “Everybody has something in common, and we want to bring them all together.”

Sitting in The Louisiana’s downstairs bar, nursing pre-show pints, Lorenzo and singer Tenda Damas look less like keepers of the holy flame of glam rock and more like a couple of football fans who’ve come straight from the terraces. They are football fans, and Roma, from their home city of Rome, are their team. But they’re even bigger glam rock fans, especially Lorenzo.

You’d be hard-pushed to find anyone with a more encyclopaedic knowledge of that era than the guitarist. When he finds out I’m from Nottingham, he immediately asks if I know We’ve Got The Whole World In Our Hands, the 1978 single recorded by local football deities Nottingham Forest and East Midlands glam-pop stragglers Paper Lace (everybody who grew up in Nottingham at the time knows it).

Earlier, Giuda had met for a drink with Phil Brown, former singer with culter-than-cult glamsters Hector, known, if at all, for their 1974 single Bye Bye Bad Days. Giuda are such big fans of Hector that they wrote their own tribute single as a belated response: 2015’s Bad Days Are Back.

With glam rock, things changed. Men started to dress like women. It was like punk without the nihilism of punk

Lorenzo Moretti

Lorenzo is a glam rock evangelist; cut him and he bleeds glitter.

“It was the beginning of a revolution,” he says in flawless English. “After The Beatles and Led Zeppelin and Genesis, they started to play simple, like how it was in the fifties. Rock music with three chords. If you listen to [Sweet’s debut album] Sweet Fanny Adams, nothing sounds like it. It’s so powerful, even more than Black Sabbath. Melodic and powerful."

He can contextualise it like a university professor, too. “At the end of the sixties, there was a rule on how men had to dress and how women had to dress. With glam rock, things changed. Men started to dress like women: Marc Bolan, David Bowie. They changed the rules. It was like punk without the nihilism of punk.”

All glam rock is equal in Giuda’s eyes, from the highbow, art-school, bacofoil-shoulder-pads strain purveyed by the likes of Roxy Music, to the hodcarrier stomp of Slade and Sweet. Lorenzo even cites shoulda-been-huge 90s electro-glam terrorists Earl Brutus as an inspiration. But Giuda themselves are a not-so-juvenile product of the working class, and their music reflects it.

Guitars gleam, drums snap, clapping hands are hoisted high – it’s the sound of 10,000 feet marching out of the factory and into the discotheque. Yet while glam is the hook, there’s more to what they do than that: they can boogie like Status Quo, snarl like AC/DC and rip it up like the Sex Pistols. And for all its throwback stylings, it’s a very 2020 sound.

“We are not clones of Slade, we are something different,” says Lorenzo. “You can listen to our records and you won’t find anyone playing like us. I think of Giuda as a modern band who took a lot from the past, but play it in a different way.”

Lorenzo and Tenda have known each other a long time. Their families lived next door to each other in a suburb of Rome.

“I was at his house the day he was born,” says Tenda, who at 41 is two years older than his bandmate. And they’ve been inseparable ever since. As kids they played football together, listened to music together, went to gigs together.

“Our first show was Iron Maiden playing A Real Live One,” says Lorenzo. “I was scared. Lots of metal guys. Then we discovered the Ramones and punk rock.”

Lorenzo was given a Ramones tape for his twelfth birthday by a friend’s older brother and instantly swerved away from Iron Maiden, metal and everything else that was happening at the time.

“I didn’t like grunge,” he says. “Ramones was the only thing I needed.”

The two of them dug deeper, hoovering up everything from the Sex Pistols to Slaughter And The Dogs. They began dressing like old-school punks, suburban brats playing at being rebels.

“Sid Vicious hair,” Lorenzo says with a laugh.

“The main thing was to be different from everybody else,” adds Tenda. “All the kids in our neighbourhood wanted to leave school, buy a big car. We wanted to be different. We wanted to travel. We really wanted to get out of that place.”

By their mid-teens they’d put together a band, Taxi, and were writing their own songs. They attracted the attention of Pierpaolo De Iulis, local underground music shaman and owner of Rome-based label Rave Up Records. Pier called up Lorenzo’s mother and asked to speak to her son about Taxi.

“He said: ‘You are genius!’” recalls the guitarist. Pier then offered to put out their records. Pier was the gateway to Rome’s punk scene – a scene Lorenzo and Tenda didn’t know existed. They spent hours drinking beers and listening to obscure punk records in his shop.

“I thought was the only person to know about the Ramones,” says the guitarist. It was Pier, too, who lifted the stone to show Lorenzo and Tenda a thriving glam rock scene. The original glam rockers had never been big in Italy.

“When glam rock started in the early seventies it was considered garbage,” says Lorenzo. “Italians only wanted to listen to intellectual music: Genesis, Pink Floyd. Bands like Suzi Quatro and Slade were never popular.”

Lorenzo knew Suzi, Slade and the rest, but he wasn’t aware of the legions of virtually unknown bands below them. At least he wasn’t until he encountered ‘junkshop glam’.

In the early 00s, a string of compilations were released celebrating the forgotten heroes of glam rock – not ‘forgotten’ as in ‘currently playing the pubs and clubs of the north-east with only one original member’, but forgotten as in ‘nobody had a bleedin’ clue who they were even at the time’. These compilations had names such as Velvet Tinmine and Boobs, the latter named after a fictional provincial nightclub where real-life turns such as Barry Blood, Stavely Makepeace and Boston Boppers could feasibly have played.

This micromovement was retrospectively nicknamed ‘junkshop glam’ by record collectors and music aficionados, on account of the fact that most of these singles could be picked up for a quid or two in the back of junk shops.

Velvet Tinmine, Boobs and their ilk were Lorenzo and Tenda’s entry to a netherworld of long-lost figures and would-be heroes. The guitarist, especially, fell hard for it.

“It was so powerful,” he says. “I was like: ‘Wow, what is this? This is something new.’”

But it wouldn’t impact on their music for awhile. Taxi continued to play straight-ahead punk rock, mainly gigging at weekends, occasionally venturing to Germany, the UK and, on two occasions, the US. It would take a tragedy to alter their course. In 2007, Taxi’s drummer, Francesco, died.

“He was a boxer, he had heart problems,” says Tenda. “He got hit, but there were some complications.”

“It was the worst period of our life,” says Lorenzo. “We were crying every day.”

They wanted to carry on playing, but without their friend it wouldn’t be as Taxi. Lorenzo and Tenda put together Giuda, bringing in bassist and former Taxi member Danilo (the current line-up is completed by second guitarist Michele and drummer Alex).

“We wanted to do something different, but it wasn’t: ‘We have to play glam rock’, because no one cared about glam rock,” says Lorenzo.

There’s footage on YouTube of the first Giuda gig, at a party in Rome in 2008.

“It’s a proper punk rock show,” says Tenda. But the bovver rock influences quickly began to assert themselves.

“We weren’t going to play [starts singing T.Rex’s hippie-glam anthem Cosmic Dancer] ‘I was dancing when I was twelve…’” says Lorenzo. “We wanted to play the tough stuff.”

Playing the tough stuff is exactly what Giuda have been doing ever since. Their four albums to date have been subtly but distinctly different, from the unashamed stackheeled boogie of 2010’s Racey Roller to the hardedged boogie of 2015’s Speaks Evil.

They’ve amassed a wide, if unexpected, array of famous fans along the way. Joe Elliott is at one end of the spectrum; at the other is former Cathedral and Napalm Death singer Lee Dorrian, who has released their last two records on his influential Rise Above label. Suzi Quatro played them on her radio show, and John Lydon was apparently impressed by them.

“Friends of ours played [2010 track] Number 10 for him when he was in Rome and he said: ‘Wow, this is great, it sounds like Gary Glitter,’” Lorenzo says proudly.

Ah, him. Giuda aren’t unaware of the minefield that comes with citing Gary Glitter’s music as inspiration. On one hand, the ‘Glitter Beat’ – that genius-level mix of snare drum and handclap defined by the 1972 single Rock’N’Roll Part 2 and powers more than one Giuda song – remains one of the greatest drumbeats ever. On the other, well, there’s the man it’s forever associated with, currently serving a 16-year jail sentence for a litany of sex offences. There’s no attempt to defend the indefensible today.

“For sure I don’t like Gary Glitter as a person,” Lorenzo stresses. “I have to separate the man from the music. But for us, Rock And Roll Part 2 is one of the most influential songs ever. It’s something we’ve studied: that music was designed to sell records, to make people dance. It’s so catchy and incredible. The sound is just magical.”

We are anti-racism, anti-sexism, anti-homophobia. We want everybody to enjoy our band

Lorenzo Moretti

The spectre of Gary Glitter is the only hint of darkness surrounding Giuda’s music. On every other level – musical, lyrical, philosophical – it’s an unalloyed force for good. ‘They ask in interviews if I like drugs or I like booze,’ Tenda sings on the knowing hymn to anti-cool that is Roll The Balls. ‘But I’m not deep in sin, cos I’m in love with aspirin.’

You can take Giuda as pure, boover-booted fun. But you could also dig deeper and find something more interesting and pointed going on. Their 2019 album E.V.A. was hung around a broad, space-themed concept that masked a deeper, more socially and politically aware concept.

“That was a way for us to talk about migrants, people who migrate from country to country,” says Tenda. “And the fact that all human beings have dignity as people.”

It’s a subject that resonates with the singer. His full name is Ntendarere Djodi Damas. His mother is Italian, of Swiss descent, his father is from Gabon in West Africa. As teenager he was beaten “very badly” due to the colour of his skin. The band’s political stance might not be explicit in their music, but they’re clear on where they stand.

“We are anti-racism, anti-sexism, anti-homophobia,” says Lorenzo. “We want everybody to enjoy our band. Every race, every gender, every sexuality.”

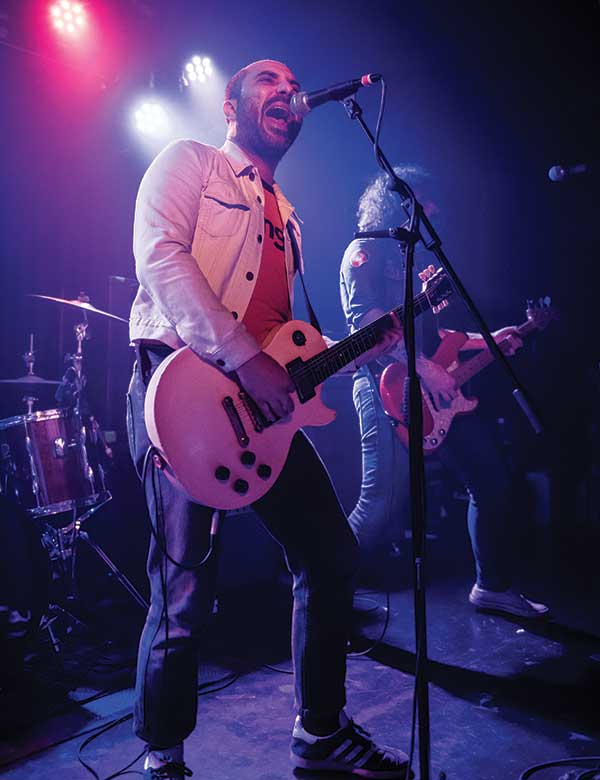

It’s difficult to tell in The Louisiana’s darkened upstairs room whether a Giuda gig is the melting pot they hope it is. But it’s unarguably the kind of joyous experience that’s all too scarce these days: equal part punk muscle, glam rock anthemics and, in the case of the choreographed, back-to-the-audience arse-waggling, pure New Faces bravado.

They shouldn’t make bands like this any more, and they didn’t until Giuda came along. There are a few others like them – they name-check their countrymen Faz Waltz, and there are pockets of glam-rock resistance fighting the good fight across Europe and the US.

A week later, when Giuda play in London, similar scenes play out over two nights in the upstairs room of North London boozer The Lexington. Inveterate music fans, Giuda are thrilled to see two musical heroes in the Lexington audience. One is Tony Sylvester, Brit-based singer with Norwegian punk pranksters Turbonegro. The other is Jamie Fry, former guitarist with Earl Brutus, one of the bands Lorenzo has name-checked as an influence.

For most other musicians, this wouldn’t matter a jot. To Giuda, you get the feeling they’re just as important as Noddy and Suzi and Bowie and Bolan. In Bristol a week earlier, I asked Lorenzo and Tenda what they want out of this.

“I want a Grammy,” Tenda replied with a laugh.

“No, no,” said Lorenzo, shaking his head. “I just want to say that I don’t care about any Grammy, or any other musical institution. I want to have more people at our shows, and I want those people to really, really enjoy themselves.”

On that score, it’s job done.

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.