“All the excesses of rock’n’roll stardom – the sex, the drugs, the parties – were open to us”: Extreme’s Gary Cherone and Nuno Bettencourt on the highs, the lows and the hedonism

Extreme’s career has taken in one huge hit, millions of album sales, a split, a reunion and a big dollop of over-indulgent rock star living. Frontman Gary Cherone and guitarist Nuno Bettencourt look back on where it all went right, and where it all went wrong.

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

On the evening of February 12 this year, anyone enquiring as to the whereabouts of Nuno Bettencourt would have been directed towards the security-ringed stage erected at centre-field at State Farm Stadium in Glendale, Arizona. There, as ex-NFL legends-turned-pundits in the stadium’s media suites paused their analysis of the first two quarters of Super Bowl LVII, the 56-year-old guitarist was calmly orchestrating the game’s musical intermission, as white-clad dancers glided through synchronised dance routines around, above and below a pregnant, radiant Rihanna. An estimated 118.7 million viewers worldwide tuned in, making Rihanna’s first live appearance in seven years the third-most watched TV show ever: 5.7 million more viewers tuned in to see Rihanna sing than to watch the game itself.

Despite the fact that he was on camera for, by his own estimation, approximately “one-point-five milliseconds” of the global broadcast of the 2023 Super Bowl half-time show – “I get it, they wanted to focus on the dancing sperm” he shrugs, his smile betraying the fact that he’s aware of how ridiculous these words sound – Bettencourt acknowledges his participation in the 35-year-old pop star’s comeback gig as a ‘bucket list’ moment. The guitarist also confesses that, as focused as he was in steering the set’s dynamic flow, from opener Bitch Better Have My Money through to the climactic combo of global mega-hits Umbrella and Diamonds, at one point he did allow himself to think: “Man, this is cool. But it’d be even cooler if I was up here with Extreme.”

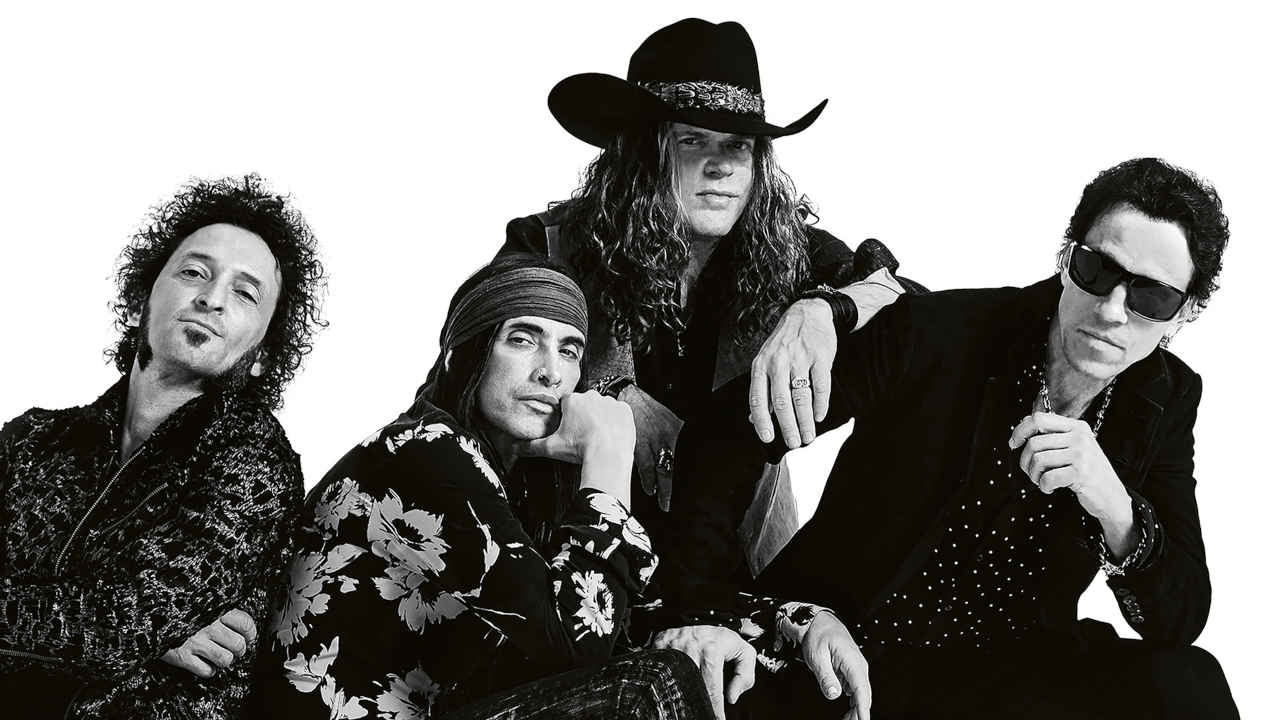

Shorn of context, Bettencourt’s declaration today that “Extreme isn’t going to play a Super Bowl half-time show” could be framed as a defeatist statement. So it’s important to clarify that as he relays these words from his beautiful home in Los Angeles, with gold and platinum presentation discs on the walls behind him, he isn’t accepting that there must be a ceiling to his hopes of what his band, who officially reunited in 2007, can achieve in their second act. On the contrary, over the course of a 45-minute conversation with the confident, charismatic guitarist, it’s abundantly clear that, ahead of the release of Six, Extreme’s first new album in 15 years, he believes the quartet still have the potential, the presence and, crucially, the songs to hit any goal they set their sights on. “Nuno and I have the same attitude: we still want to conquer the world,” Extreme’s frontman Gary Cherone affirms. “We still want to play the biggest stages, we still have bucket-list dreams. We still feel like a new band with something to prove.”

The final song on the new Extreme album is titled Here’s To The Losers. Over Bettencourt’s finger-picked acoustic guitar arpeggios, Cherone croons: ‘Hey, you gave it your best shot, you gave it all you got, it wasn’t quite enough.’ If that title is somewhat tongue- in-cheek, the song itself is sincere and heartfelt; an empathetic celebration of the underdogs, the nearly men, the coulda-been-someones. Today, Cherone reveals that it was written as a response to Queen’s triumphalist anthem We Are The Champions. “I’ve had that title in my head for ever,” he says. “It’s like, okay, you are the champions? Cool, okay, congratulations. But what about the rest of us? We matter too!”

For Cherone, isolating the “pinnacle” of his band’s first act is easy. On April 20, 1992, standing together side-stage at Wembley Stadium during the Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert For Aids Awareness, he recalls himself and Bettencourt virtually levitating with joy as the day’s ‘pinch me, I’m dreaming’ moments kept coming.

Sandwiched between Metallica and Def Leppard on the most star-studded concert staged in the UK since Live Aid, Extreme’s decision to follow Brian May’s on-stage introduction by devoting the lion’s share of their mid- afternoon set to a respectful tribute medley of Queen classics rather than merely pushing their double-platinum- selling second album Pornograffiti was a masterstroke: the sight of the 72,000 stadium audience clapping in unison during their snippet of Radio Ga Ga was the stuff of rock’n’roll dreams. Even this, however, paled alongside the moment they (along with George Michael, Guns N’ Roses, Metallica and more) were ushered from the wings to stand behind Liza Minelli as Freddie’s dear friend delivered a spine-tingling performance of We Are The Champions with May, John Deacon and Roger Taylor.

“What a day,” Cherone marvels. “That was one of our best ever performances, and the fact that it was captured on film for all time is amazing. I play basketball twice a week with guys my own age, and those guys couldn’t give a shit about Extreme. To them I’m not ‘Gary from Extreme’, I’m just some guy shooting hoops. And I love that. But every now and then a couple of new guys will join, and at some point maybe they’ll discover the Freddie Mercury show on YouTube, and they’ll look at me differently for a week or two. But we never thought we were the shit. My mother would have smacked me in the head if I’d started acting like Mister Rock Star!”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Rise, the ballsy, powerful first single from Six, released at the beginning of March, is described by Cherone as “a cautionary tale on the rise and fall of fame”. “You get seduced into it,” he said in the press statement accompanying its release. “Once you’re on top, they’ll rip you apart and tear you down. That’s the nature of the beast.”

It says something about Cherone’s level-headed nature that when he’s asked whether the song’s lyrics are drawn from bitter experience – given that within five years of Extreme’s best-known song, monster-ballad More Than Words, topping the Billboard Hot 100 in June 1991, the band had broken up – he initially looks puzzled by the question, then weighs it up in silence for a few moments before answering.

“It’s funny,” he says, “I wrote the song, you know, looking out, I never applied it to myself. But yeah, I guess I could apply parts of it to Extreme. Was becoming a successful band everything we expected? It was everything we expected and more. Our first record [1989’s Extreme] did okay. And for the first nine months touring [follow-up] Pornograffiti we were playing in clubs, to kinda the same audience, as the record didn’t catch on. And then More Than Words comes out, and explodes on MTV, and suddenly we’re being carried away by a whirlwind. We were just trying to hang on. All the excesses of rock’n’roll stardom – the sex, the drugs, the parties – are now open to us. But we could see temptations as potential pitfalls, and we just kept our heads down.”

“Do I love women?” says Nuno Bettencourt, a man who presumably has become inured to forever being the most handsome man in any room. “Of course I do. Do I love to have a bit of a buzz? Of course I do. And I’d be lying through my teeth if I said some of that excess didn’t happen. But music was always my drug. And I’m grateful for that, because on tour, outside our band, I witnessed heavy shit. I mean, there are five or six bands I toured with in the nineties whose singers are now dead.

“When you’re a kid, dreaming about being a rock star, visualising playing your songs at Madison Square Garden, that’s the whole dream. So you prepare for that. But then you realise that the other ninety per cent of what you have to deal with, you’re just not equipped for. So numbing yourself with drugs and alcohol and sex just to cope can be appealing. I wish there was a course we could have taken back then, Rockstar 101, saying: ‘Guys, this is what the oven feels like when you touch it when it’s hot.’ This lifestyle is like being in a pressure cooker. And one day that pressure cooker will fucking explode. I wish I’d known that, because maybe today we’d be talking about Sixteen instead of Six.”

When Extreme broke up in 1996, at the end of their touring commitments for their fourth album Waiting For The Punchline, it was because Bettencourt wanted to strike out on his own. His first solo album, Schizophonic, duly emerged the following year. Between 1997 and Extreme’s return in 2007, the guitarist released music with his bands Mourning Widows and Population 1 (later renamed Near Death Experience, then DramaGods), before partnering with former Jane’s Addiction vocalist Perry Farrell in Satellite Party, whose sole studio album, the underrated Ultra Payloaded, was released in May 2007.

“I was a big Jane’s Addiction fan, and a big Perry Farrell fan,” he gushes. “He’s a fucking incredible performer, an incredible writer, and so just to get in the room to do stuff with him was amazing. But on tour there were some.... personal, cultural kind of things happening that I don’t even want to get into, and I left. When conversations about Extreme returning started, I was ready.”

So too was the singer, the guitarist’s musical soul mate, with whom he first bonded in 1985 over a mutual love of Queen II. Cherone’s first post-Extreme engagement could hardly have been more high-profile, or come with greater pressures. It was Ray Danniels, then managing both Extreme and Van Halen, who suggested Cherone audition to become Van Halen’s new frontman, following the exit of Sammy Hagar in the summer of 1996. Cherone insists that the full extent of his aspirations at the time was to grab an opportunity to sing Jump with three-quarters of the band who recorded it, and to hear some cool Van Halen stories he could share with his guys in Boston, but says Bettencourt encouraged him to believe that he was the perfect fit for the role. When it’s put to him that being Van Halen’s frontman took some serious balls, he laughs gently and says: “Or maybe naivety.”

“I remember Nuno saying: ‘Of course, you’re going to get this job. Your whole career has been leading to this.’ And that was very encouraging. And when Eddie [Van Halen] and I met, it just clicked. He was so human, and so inviting, and working together was a pure joy. People can think whatever about the record we made [Van Halen III], but I’m proud of it, and so was Eddie.”

This writer can attest to this. Ahead of the release of that album, in the spring of 1998 I interviewed Cherone and Eddie Van Halen at Eddie’s’s 5150 studio, and the guitarist could not have been more effusive in his praise for Cherone, who he hailed as “very talented, very gifted, and a down-to-earth human being”.

“I believe that the man or woman upstairs put us both here to play music,” he stated, his hand on Cherone’s shoulder, “and it feels like I’ve been waiting for twenty years for this guy to come along.” However, the world’s music press was less impressed by the first and only Van Halen album Eddie co-wrote while sober. “The fundamental problem with this album is the songs,” long-time Van Halen fan Paul Elliott wrote in his one-out-of-five review in Kerrang! magazine. “They’re shit.”

“I think there’s some great songs on that record,” Cherone counters today. “It’s a different record to what Van Halen did before, but it’s a moment in time, and the songs stand up well.” Van Halen III would become the first Van Halen album not to go platinum in the US. Cherone left the group on amicable terms in late 1999. If his discography since is modest – a 2002 album with Tribe Of Judah (Exit Elvis), two albums with Hurtsmile, a group he formed with his brother Markus on guitar – his understated pride in those records is tangible, and genuine. As is his excitement at the prospect of the world hearing the new Extreme record this summer.

His enthusiasm is justified. While there are moments on Six that are clearly indebted to longtime band influences – the upbeat, sunshine-streaked, beach bar singalong-in-waiting Beautiful Girls (‘All around the world, there are so many beautiful girls’) could be Dave Lee Roth-era Van Halen at their most horny, the prog-metal X Out sounds like early Queen (and indeed fellow Queen devotees Muse) – it’s fair to say that no one else is going to release an album that sounds like this in 2023. Bettencourt’s guitar-hero flexes power on the attitude-laced #Rebel and the dirty grind of Banshee. At the other end of the album’s sonic spectrum there’s the tender, classy Hurricane (about “navigating through a storm of loss”, says Cherone) and the sweet, harmony-stacked hug of Other Side Of The Rainbow (about “restoring one’s faith and love. Everyone has been hurt”). If you’re an Extreme fan, Six is everything you would hope for from the band in 2023. If you’re not, you might just be seduced.

Bettencourt hopes you like the record. But if you don’t, that’s okay too, because he didn’t make this record for you. “Let me tell you something,” he says, leaning forward. “Any fucking artist who says they’re doing this for the fans is fucking lying to you. They’re full of shit. We do this for ourselves, man. We do this because we need to do it. I want a rock album in 2023. I’ve got songs,” he says. “Hundreds of songs. So the reason we haven’t put out an album in fifteen years has nothing to do with a lack of songs. We could have cashed in and made an album every year, but I would never release an album that I’m not fully emotionally connected to. And Six is worth the wait, trust me.”

We have one final question for Extreme’s guitarist: if the gold and platinum discs on his walls are signifiers of Extreme’s past successes, what is success going to look like for Six in 2023? “That’s a great question,” he replies, “because you would maybe think that it’s going to be something different now I’m older and wiser. But it means the same as it always did: success to me is making an album that I’m excited about, and watching proudly as this child makes its way out into the world.

“Those discs on the wall?” he continues, pointing behind him. “When I moved to this house, eight years ago, they were in fucking storage collecting dust. They didn’t mean anything to me. And then I realised that I needed to see them for myself, to say: ‘Hey, you fucking did it, dude.’ I don’t see a platinum disc as proof of one million album sales. In my head it’s like: ‘Yo, you sat in a fucking bedroom as a Portuguese immigrant and fucking put a band together, and you fucking did it.’ They’re a reminder of sleeping in our rehearsal space, of turmoil with the band, of all the hardships... and the fact that it was all worth it. What happens with Six now we can’t control, but this is real, and we’re proud to share it with you.”

A music writer since 1993, formerly Editor of Kerrang! and Planet Rock magazine (RIP), Paul Brannigan is a Contributing Editor to Louder. Having previously written books on Lemmy, Dave Grohl (the Sunday Times best-seller This Is A Call) and Metallica (Birth School Metallica Death, co-authored with Ian Winwood), his Eddie Van Halen biography (Eruption in the UK, Unchained in the US) emerged in 2021. He has written for Rolling Stone, Mojo and Q, hung out with Fugazi at Dischord House, flown on Ozzy Osbourne's private jet, played Angus Young's Gibson SG, and interviewed everyone from Aerosmith and Beastie Boys to Young Gods and ZZ Top. Born in the North of Ireland, Brannigan lives in North London and supports The Arsenal.