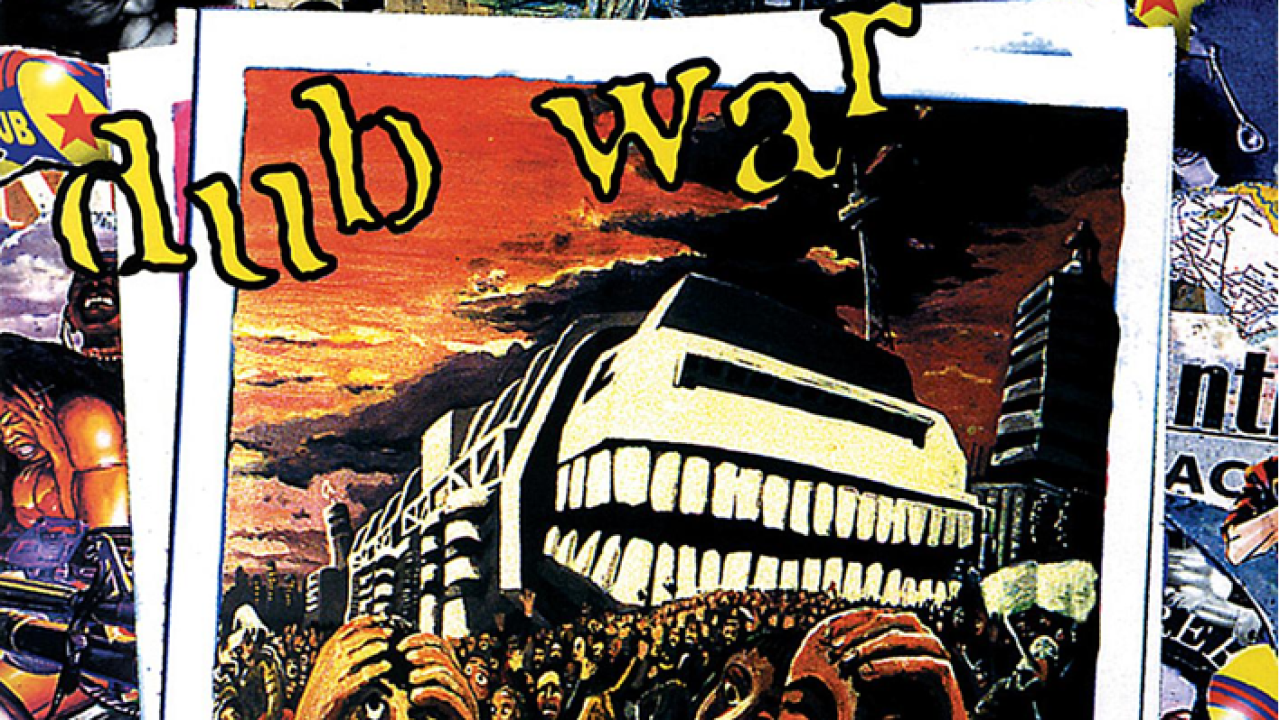

Dub War’s Pain: ragga-metal and revolution on a lost 90s classic

Before he put together Skindred, Benji Webbe was starting a ragga-metal revolution with Dub War

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

When discussing the story of rock and metal in the ’90s, it has become tiresomely predictable that the efforts of Dub War are overlooked. At a time when the rulebook was being routinely set alight and thrown out of the window, this eight-legged riot-starting machine from Newport, South Wales were leading the creative charge in the UK, mirroring the efforts of numerous bands on the other side of the Atlantic but offering something utterly unique at the same time.

Dub War arrived fully formed and seemingly oblivious to the incendiary power of their own music, skilfully smashing rock, punk and metal together with reggae and hip hop, resulting in a fiery and invigorating brew that should, had the planets aligned in the correct way, turned the band into an international sensation akin to those few bands, Rage Against The Machine and Faith No More among them, that had exhibited a similar disregard for convention and been duly rewarded. That it never quite happened that way remains one of the more frustrating phenomena to occur during the trials and turmoil of the UK rock scene in the ’90s.

Formed in 1993, Dub War were so powerful and distinctive that their impact on the live gig circuit in the UK was immediate. They swiftly became known as progenitors of so-called ‘ragga metal’, but as vocalist Benji Webbe cheerfully explains, the birth of the band’s sound was never as meticulously planned as it may have seemed from the outside.

- Skindred’s Nobody: the story behind the song

- The 50 best Metallica songs of all time

- Every Slipknot album ranked from worst to best

- Metal album covers with Simpsons characters wins the internet today

“It all started because I wanted to do some real rock music,” he tells Hammer. “I always liked rock music anyway, but I’d been travelling around the country doing these reggae sound systems and I just got pissed off with it. I’d always end up with a tenner and small bag of weed instead of the 200 quid they were supposed to pay me, so after a while I thought ‘Fuck this!’ and started looking for something else to do. Then I heard about this local rock band that were looking for a singer, so I went down to the rehearsal room and that’s where I met the rest of Dub War.”

Determined to move on from his roots in the reggae scene and to take a fresh creative direction by embracing the rock’n’roll world, Benji was excited to have found such suitable musical partners, but it soon became apparent that his new bandmates were eager to explore the possibilities presented by working with such a versatile vocalist.

“It all felt right straight away, but I really didn’t want to do the reggae vocals anymore,” he says. “I wanted to try being a rock singer, so I deliberately didn’t do any of the reggae stuff, but one day Jeff [Rose, Dub War guitarist] asked me to try some reggae vocals over a new song we were writing and that was it. It was obviously really good, so that’s why we ended up sounding like that. The rest is history!”

Ironically, despite the fact that their sound seemed to flow from the same melting pot of styles that had inspired Faith No More and many other riff-wielding freewheelers, Benji insists that his own knowledge of Dub War’s supposed musical ancestry was almost entirely non-existent when the band was formed.

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“At the time I didn’t know who Faith No More were, know what I mean?” he laughs. “Everyone kept saying that I sang like Mike Patton and I didn’t know who he was! It’s the same with Bad Brains. I’ve never owned a Bad Brains record in my life, but people always say ‘Oh, you sound just like [Bad Brains frontman] HR, man!’ It’s crazy but I never heard that stuff, I promise!”

Inspired by the realisation that they could successfully combine all their influences and produce something genuinely fresh, Dub War got to work immediately and recorded their debut release, the six-track Dub Warning mini-album that emerged on their own Words Of Warning imprint late in 1993. Meanwhile, they hit the road with a vengeance, notching up as many live shows as possible and rapidly earning themselves a reputation as the most stupidly exciting live act the UK had produced in many years.

“Everyone was being blown away!” chuckles Benji. “Hundreds of record labels came to see us, and they were all blown away too. Eventually some guy from One Little Indian Records said they were interested, but they ended up signing Skunk Anansie instead. They were obviously looking for something a little bit like us, but we just weren’t it! Then Digby [Pearson, Earache Records owner] came along while we were recording the mini-album. He came to the studio in Wales and said, ‘I really love what you’re doing…’ and then he came to a few shows. Soon he made us an offer and off we went.”

Widely regarded as one of the most important labels in extreme metal, Earache Records were known primarily for their impressive roster of death metal bands, so the arrival of the eclectic and forward-thinking Dub War prompted more than a few raised eyebrows among the underground metal world. However, Benji was quite happy for his band to be viewed as a curious detour for the otherwise proudly extreme label.

“We were always the weird kid in the class anyway, so it wasn’t surprising to us to be on Earache,” he states. “Digby wanted to stretch the label and find a more commercial angle and he did everything he could do for us. We had an amazing three years on Earache. We travelled the world! It was a really good time and it was a great relationship.”

With their label fully behind them, Dub War needed to follow up their low-key debut as soon as possible. At the height of their powers as a unit and with no shortage of material to choose from after nearly two years together, the band were itching to hit the studio to make their first full-length album. Late in 1994, they jumped in the van and headed to Chapel Studios in South Thoresby, Lincolnshire to meet up with producer Brian New.

“We were touring that set with all those songs for 18 months before Earache got involved,” recalls Benji. “All the songs like Nations and Strike It, we were playing them for two years before we recorded them, so we knew what we were doing and the vibe was really good. Brian New’s greatest claim to fame was working with Will Smith, so we were in good company! He did a great job and I think that’s why Pain still sounds really fuckin’ great all these years later. We ended up working with Paul Schroeder on the next album [1996’s Wrong Side Of Beautiful], and he was a great friend of ours but I don’t think we ended up with a great album. Brian was like a chemist, and Paul was a free spirit, and it sounded like he’d thrown the tapes in a washing machine and spun them around! Ha ha! If I could do the second album again, I’d do it with Brian.”

Kicking off with the vicious grooves of Why and the pounding hooks and vivid sloganeering of Mental, the first Dub War album came pretty close to capturing the feverish excitement of the band’s live shows. Covering a vast amount of musical ground, ranging from the ragga-core belligerence of Strike It to the dubby melodic rock of Gorrit and on to the mischievous reggae shuffle of Fools Gold, Pain stood in stark contrast to the somewhat one-dimensional, formulaic approach taken by bands in the nascent nu metal scene. It was also extremely refreshing to hear a band who weren’t afraid to touch upon social and political issues in their lyrics, as Benji’s worldview and enthusiasm for propagating a positive message became one of Dub War’s most distinctive characteristics.

“We were just trying to deliver a social message of people coming together, of unity and pushing the bullshit out the window,” he says today. “We didn’t think about using the band to escape from where we were brought up. We just wanted to be uplifting. You might not be able to do anything about the madness on your streets, but you could become a better person and that was our philosophy. I’d gone from being this fuckin’ hood-rat and running around in Newport, to joining the band and travelling the world, and I became this born-again good guy! I didn’t get up to no shit. The rest of the band were into all this madness and debauchery every night, and I was sat at the back of the bus with Rey Oropeza from Downset, reading Bible pages, you know? While everyone else was doing lines of coke off girls’ backsides! Ha ha ha! So Dub War was a life-changing experience for me – I’ve always wanted to share that with people through the lyrics.”

Although very satisfied with the outcome of his band’s sessions at Chapel Studios, Benji does harbour one complaint about his first experience of a residential recording studio and all its fringe benefits.

“I got fuckin’ fat!” he laughs. “Before we went there I said, ‘Right, I’m going to train and run every day!’ but it was the first time any of us had had someone cooking for us at all hours of the day, and we just fuckin’ ate and ate! I remember finishing the album and we had to do some photos and I put on my trousers and they were too tight! But it was a great studio and we had a really good vibe there. All records should be done like that, away from everything in a studio in the country and all you’ve got to think about is the songs and the band.”

Released early in 1995, Pain was an instant and considerable success for Dub War. It consolidated their burgeoning reputation as one of UK rock’s most important new bands, provided rock clubs with fistfuls of guaranteed floor-fillers and enabled its creators to bring fans of numerous different genres together for one life-affirming and righteously deafening party that is still going on to this day via Benji’s ongoing career with Skindred.

“When I listen to Pain now, it sounds fantastic,” he states. “If we did it now, the lyrics would be different, I think, because I’m singing about different things these days, but as an album it stands up against anything. I have a friend who’s a DJ and he always puts on a Dub War tune for me when I see him. He’s such an asshole! Ha ha ha! I always feel a bit embarrassed but I also think, ‘That sounds fuckin’ great!’ Put it up against anything that’s happening today and Dub War comes out OK, I think.”

Dom Lawson began his inauspicious career as a music journalist in 1999. He wrote for Kerrang! for seven years, before moving to Metal Hammer and Prog Magazine in 2007. His primary interests are heavy metal, progressive rock, coffee, snooker and despair. He is politically homeless and has an excellent beard.