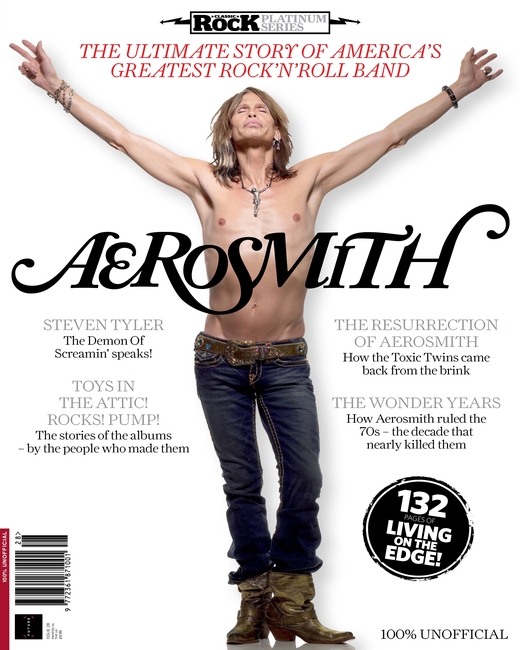

“We were drug addicts dabbling in music, rather than musicians dabbling in drugs”: The unhinged story of Aerosmith’s Draw The Line, the album that sent them crashing off the rails

Drugs, dysfunction and 1977’s Draw The Line album sent Aerosmith into a tailspin that would take a decade to pull out of

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

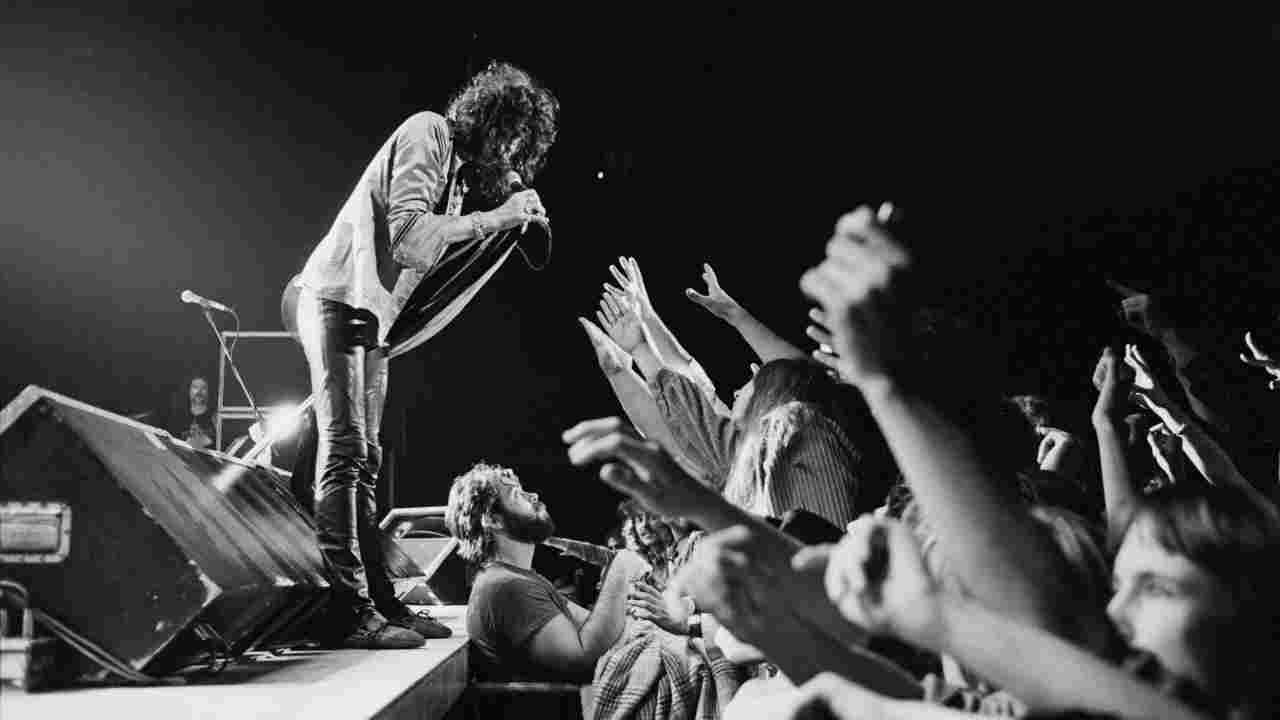

As 1977 rolled in, Aerosmith were flying high. In January, the band’s latest single Walk This Way, belatedly extracted from 1975 album Toys In The Attic, hit No.10 in the US. And in February, when they toured in Japan for the first time, they experienced a level of hysteria akin to Beatlemania.

There was no rock band on Earth bigger than Led Zeppelin, but Aerosmith were rising fast. As their producer Jack Douglas said: “Kiss was their only competition, at least among American rock bands.”

And yet, in the early summer of ’77, when Douglas started work on Aerosmith’s fifth album, Draw The Line, the problems within the group were plain to see. Hard drugs had taken a hold on the band’s two leading figures, singer Steven Tyler and guitarist Joe Perry. As the latter would put it: “The Beatles recorded The White Album, right? Well, Draw The Line was our Blackout Album.”

It was an album created out of chaos, and it marked a turning point in the life of America’s greatest rock’n’roll band. In its wake came two years of insanity – near-fatal car crashes, on-stage meltdowns, drug mania and fights between their wives and girlfriends, culminating in the shock exit of Joe Perry in 1979. And strangest of all, it was during these wild years, when the band was at its most dysfunctional, that some of Aerosmith’s greatest music was made.

The scene for the recording of Draw The Line was the Cenacle, a vast mansion set in 100 acres in a remote part of New York State near the village of Armonk. In 1977 the owner of the Cenacle was a psychiatrist who planned to turn the old place into a residential home for troubled adolescents. “Instead,” joked Aerosmith’s bassist Tom Hamilton, “he got us.”

By the time the band members arrived in June, Jack Douglas and his team had set up a mobile recording studio on the ground floor, with heavy cables running from room to room. For added natural ambience, Joey Kramer’s drums were recorded in the chapel, and Joe Perry’s rig was installed in a walk-in fireplace. The difficulty for Douglas was in getting the band into a working routine. As Perry later admitted, “We were drug addicts dabbling in music, rather than musicians dabbling in drugs.” Their hazardous recreational habits also extended to racing their sports cars, Ferraris and Porsches, on the surrounding country lanes, and messing around with firearms, Perry having recently added to his private arsenal a semiautomatic Thompson machine gun.

The days and nights passed in a blur. “We were out there at the Cenacle,” said Tyler, whose erratic mood swings were dictated by whatever he was on – snorting fat lines of cocaine one moment, then gulping downers, in particular the sedative-hypnotic Tuinal. During one dusk-till-dawn bender, he and Kramer set out at 5am to shoot beer cans with .22 rifles, only for Tyler to pass out with the gun in his hands before a shot was fired. Perry, meanwhile, was using heroin, breakfasting on White Russian cocktails, and wandering around the place “glassy-eyed”, as Douglas recalled.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

With Tyler and Perry zonked, shut away in their second-floor rooms for days at a time, the band was, in Hamilton’s words, “split in two”. Most evenings, it was just the trio of Hamilton, Kramer and guitarist Brad Whitford working on tracks. Tyler, holed up in his room, was struggling to write lyrics, and on the rare occasions when Perry did show, he was barely able to string a few notes together – in Douglas’ estimation, “totally wrecked”. Perry never denied it. By this stage, he said, “Steven and I had stopped giving a fuck.”

After six weeks at the Cenacle, with the album still unfinished and tour dates looming, the band headed home to Boston. But in the condition these guys were in, minds frazzled, two of them were lucky to make it back alive. Kramer reckoned he was doing over 130mph in his Ferrari when he fell asleep at the wheel and crashed into a guardrail. He was hospitalized with a head injury but quickly discharged with seven stitches. The $19,000 Ferrari was a write-off. Perry was also driving at high speed when he lost control of his Corvette and hit an unmarked police car. He emerged unscathed, and as he later noted, with some amusement, the cop kindly took him to a nearby Dunkin’ Donuts.

Others might have seen this as a wake-up call, but not Perry. At home during a brief period of downtime, he got loaded on opium, rolled into a ball and swallowed whole, drank vintage wine like it was water, and rode his luck time and again in what he described as “a series of car accidents”. The madness continued unabated on tour, for which the road crew packed a chainsaw for Perry to dismantle hotel furniture.

What was officially named The Aerosmith Express Tour – but known among the band’s long-suffering crew as The Lick The Boots That Kick You Tour – ran from June to October, beginning and ending in the US, with European dates in between. Throughout this period, Jack Douglas was kept busy: taping shows for a live album and, during breaks in the tour, conducting the final sessions for Draw The Line at The Record Plant studios in New York City, where Tyler applied what little discipline he had to finishing his lyrics and vocals.

In Europe in August, a performance at the Lorelei Festival in Germany was cut short when Tyler collapsed after just three songs, but at the Reading Festival, the band turned it on, winning over a rain-soaked audience mired in mud. And it was during their time in the UK that Perry recorded his solos for the new album’s title track at AIR Studio in London, owned by The Beatles’ producer George Martin. On that occasion, Perry played with genuine conviction as his new friend, Queen guitarist Brian May, watched on.

In October, back on home turf, there was another close call during a show at the Philadelphia Spectrum. With 17,000 fans in rowdy mood, an M-80 firecracker was thrown on stage, the deafening explosion leaving Tyler with a burned cornea and Perry with a burst artery in his right hand. As Whitford said: “Steven could have been blinded.” Later that month, as Tyler and Perry added the finishing touches to Draw The Line at The Record Plant, they had even more reason to count their blessings. On October 20, a plane carrying Southern rock band Lynyrd Skynyrd crashed near Gillsburg, Mississippi, killing six of the occupants, including singer Ronnie Van Zant and guitarist Steve Gaines. This plane, a Convair CV-240, had been offered for Aerosmith’s use earlier that year, but had been declared unsafe by the band’s head of flight operations.

What happened to Lynyrd Skynyrd had a profound effect on the members of Aerosmith. As Joe Perry said: “It was a terrible tragedy, and we just considered ourselves incredibly lucky. To be that close to it, and knowing those guys, it was really a blow.” But in the immediate aftermath, just a few days after the disaster, Aerosmith hit the road again, and while the shows were selling out, the flagship single for the new album, its title track, bombed. “It didn’t make the Top 40,” Tyler said. “And this was supposed to be a huge album for us, a big follow-up to our best work.”

A turbulent year for the band ended with the album’s release on December 9. And just as Tyler knew how much was riding on it, so did Jack Douglas. As he explained: “It took us six months and half a million dollars to make that record.”

Demand for a new Aerosmith album was sky-high, and Draw The Line took off like a rocket. The bottom line was what mattered to Columbia Records, and according to Douglas, this was “the fastest selling record the label ever had”. But by January 1978, the album had peaked at Number 11 in the US – a major disappointment after the previous record, Rocks, had reached Number Three. And in Rolling Stone magazine, a review of Draw The Line was as stinging as it was perceptive: “Chaotic to the point of malfunction, with an impenetrably dense sound adding to the confusion… This album shows the band in a state of shock.”

Going for the jugular, that review pinned Draw The Line as “a truly horrendous record”. The truth of it was not quite so simple. Certainly, this album was no match for what came before, the twin peaks of Toys In The Attic and Rocks. But there was a powerful intensity, a cocaine-induced mania, in the title track and the Perry-sung Bright Light Fright, the latter inspired, so Perry claimed, by the “energy” of the Sex Pistols – evidence, albeit slight, that some outside influence could permeate his fazed consciousness. There was depth in Kings And Queens, a weird and heavy trip in which Tyler sang of ancient European history, guillotines and Vikings – Walk This Way this was not.

The album’s best track, I Wanna Know Why, proved that Aerosmith could still sound as cool as fuck, even if Tyler and Perry had stopped giving a fuck. And while their version of Milk Cow Blues – a 1930s song credited to American bluesman Kokomo Arnold and famously recorded by Elvis Presley in the 50s – was laid down because they were short on original material, it had a real swing to it, and carried a little poignancy following the death of Elvis on August 16, 1977.

What was lacking in Draw The Line was anything approaching the beauty in songs such as Uncle Salty and You See Me Crying from Toys In The Attic, and the ballad Home Tonight from Rocks. This album, born of excess, was all hard edges. The only lightness of touch was in the illustration on the cover, a portrait of the group by caricaturist Al Hirschfeld.

As Jack Douglas put it: “Draw The Line is a classic title that says it all, the coke lines, heroin lines, drawing symbolic lines and crossing them all – no matter what.”

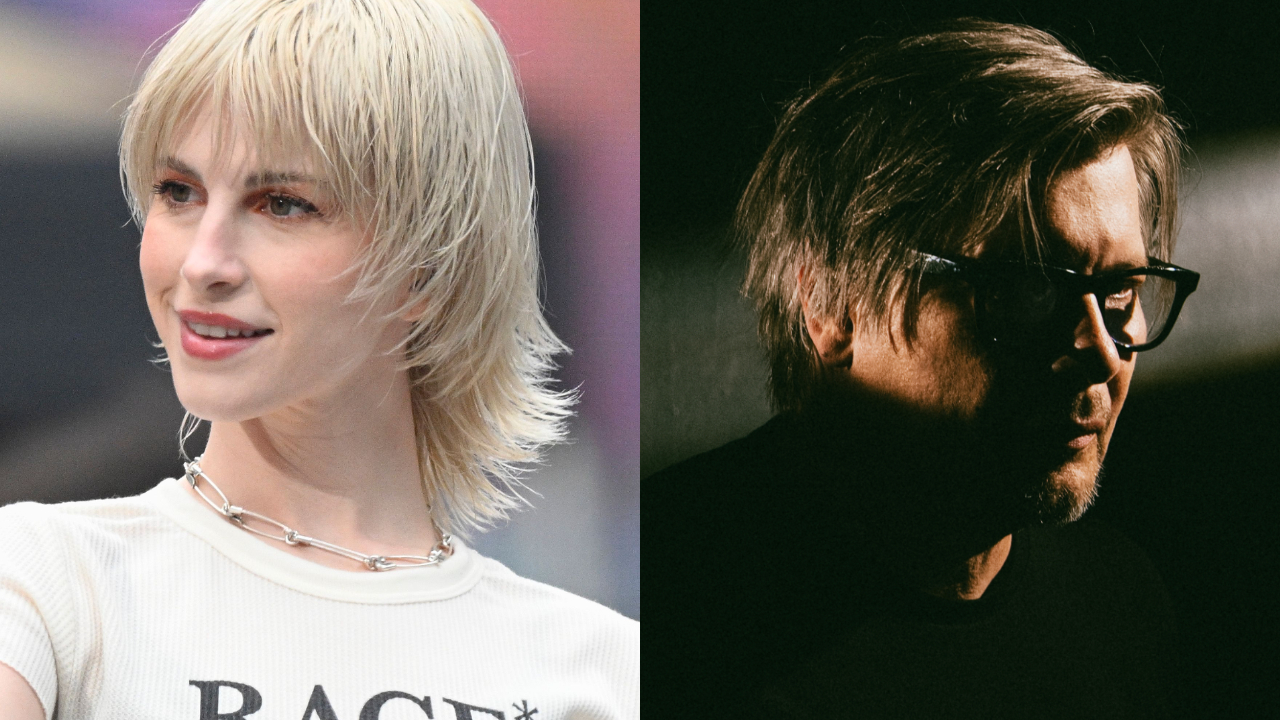

By this stage, it was no secret that Aerosmith were into the hard stuff, Tyler and Perry most of all. “The press started referring to Joe and Steven as The Toxic Twins,” Tom Hamilton said. “We started hearing rumours that we were breaking up when word got out how crazy things were.” What was unknown, outside of the band’s inner circle, was the twisted little drama playing out in Tyler and Perry’s personal lives.

Perry and his wife Elyssa were tight with David Johansen, singer for the New York Dolls, and his wife Cyrinda Foxe, a model, actress and protégé of Andy Warhol. Johansen had even co-written the song Sight For Sore Eyes from Draw The Line. When it was discovered that Tyler and Cyrinda were having an affair, Elyssa was mortified. “I felt like an idiot,” she said. “David was good friend.” Her worst fears were confirmed when Cyrinda left Johansen for Tyler, and then revealed that she was pregnant.

With the relationship between singer and guitarist deteriorating, the tension heightened by non-stop drug use, Aerosmith manager David Krebs devised a simple strategy for 1978 in an effort to keep the band together. As he explained it: “We had reached the top, but the band was dying. I wanted to give them time to work out their problems. We came up with these giant events. That’s how they spent most of the year, headlining ten major festivals.”

One such event came on March 18, California Jam II in Ontario, 30 miles from Los Angeles, where an audience of 350,000 saw Aerosmith topping a bill featuring Ted Nugent, Foreigner, Heart and Santana. And it was during this trip to California that this band of Beatles fans got to work with George Martin, the man known as ‘the fifth Beatle’.

Martin was producing the soundtrack album for the movie Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, a musical comedy, loosely based on The Beatles’ most famous work, starring the Bee Gees and Peter Frampton, and created by Robert Stigwood, the manager of the Bee Gees and the brains behind the box-office smashes Saturday Night Fever and Grease. The Sgt. Pepper movie had Beatles songs sung by a diverse cast – the Gibb brothers and Frampton, Alice Cooper and the comedians Frankie Howerd and Steve Martin. And for Aerosmith, there was a cameo role in which they played to type as ‘The Future Villain Band’, performing a rocking version of the Fab Four’s funkiest number, Come Together. The track was recorded with Martin in just two takes, and while the movie and soundtrack album would bomb, Aerosmith would have a Top 30 hit with Come Together in September, the month in which Tyler and Cyrinda were married.

Through that summer, the band played more of those giant events. On July 4, American Independence Day, they top-billed at the Texxas World Music Festival at the 100,000-capacity Dallas Cottonbowl, with Ted Nugent and Heart again as support acts, along with Journey and Eddie Money. They also played a few low-key club shows, billed as Dr. J. Jones And The Interns, which were recorded by Jack Douglas for the live album that was released on October 27. They named it Live! Bootleg, and the titled implied, it was, by design, the antithesis of Peter Frampton’s sweet-sounding mega-hit Frampton Comes Alive!

The true measure of what Aerosmith delivered in Live! Bootleg was summed up by Guns N’ Roses guitarist Slash, who was just a kid of thirteen when the album came out. “That was the big one for me,” he said. “Live! Bootleg is one of the most underrated albums of all time, one of the best live rock’n’roll albums ever made. It started the trend for me to go out and discover new bands by buying their live albums, because that way I could get all the best songs and for me the whole live thing was the most exciting thing in the world. The way that Live! Bootleg starts with Back In The Saddle, that whole intro with the crowd going crazy and the flash-pots going off, that whole build-up, made it so exciting to me.”

Live! Bootleg was a triumph, but within a month of its release, with the band back out on tour, a shocking incident in a Chicago hotel pushed Tyler and Perry even closer to breaking point. An argument between Elyssa and Cyrinda, the latter eight months pregnant, escalated into a brawl, in which Elyssa was alleged to have kicked Cyrinda in the stomach. Brad Whitford’s wife Karen witnessed what happened, later recalled it as “a very ugly scene”, and noted, “Things between Steven and Joe went immediately downhill, as you can imagine.”

Fortunately, Cyrinda’s pregnancy was not affected. On December 22, she gave birth to a healthy daughter, whom they named Mia. But for the band, the writing was on the wall.

In January 1979, even as Live! Bootleg rose to No.13 on the Billboard chart, Rolling Stone stuck the knife in again. “Aerosmith is a dinosaur among bands, the last of a generation of rock’n’rollers being edged out by more streamlined competition like Boston, Foreigner and Fleetwood Mac,” proclaimed the magazine.

But it wasn’t this new breed of Adult Oriented Rock band that was hurting Aerosmith. Nor was it the advent of punk rock and new wave. The damage was coming from within. Aerosmith was a band self-destructing – with the drugs and the booze, and with the enmity between their women that was effectively a proxy war between the guys themselves. Tyler and Perry had always been the axis on which the band revolved, but in the summer of ’79, that bond was broken.

In the preceding months, the band was still functioning, to a point. They were still doing the big shows – headlining the California Music Festival at Memorial Coliseum in Los Angeles on April 7, with Nugent again on the undercard, alongside Van Halen and Cheap Trick, and 100,000 tickets sold. In May, work on a new Aerosmith album began. But on July 28, at another marquee event, the World Series Of Rock festival at Cleveland Stadium, the shit hit the fan.

The line-up that day was out of this world: below Aerosmith and, as usual, the Nuge, were Journey, Thin Lizzy, AC/DC and Scorpions. But when Aerosmith got up on stage, it wasn’t pride, the desire to prove they were still top dogs, which had them fired up. It was hatred for each other. Moments before show time, in a backstage trailer, Elyssa Perry had traded insults with Tom Hamilton’s wife Terry, thrown a glass of milk at her, and in the ensuing scuffle, all five members of the band ended up throwing punches. All of that bad energy went into what Elyssa described, mischievously, as “the best show of the tour”. But once it was done, and they were all back in the trailer, Tyler and Perry went right at it. As Tyler recalled: “Joe goes, ‘Maybe I should leave the band.’ I said, ‘Yeah, maybe you fuckin’ should.’ Joe goes, ‘Oh yeah?’ And gets up. And I yell: ‘FUCK YOU, THEN! GET THE FUCK OUTTA HERE!’ And he left.” Tyler concluded, funnily but somewhat simplistically: “Aerosmith literally broke up over spilt milk.”

In the weeks that followed, as rumours of Perry’s exit circulated in the rock press, the rest of the band got back to work on the new album at Media Sound studios in New York, while also auditioning new guitarists. One of the candidates was Michael Schenker, the mercurial German genius who had walked out of two major bands, UFO and Scorpions. It was Schenker’s brusque manner – as Tyler quoted him, “Before I join your band I vant it clear I’m taking over right now!” – which turned them off. Schenker was similarly unimpressed. “Steven,” he said, “was not in a good shape.” In the end, it was a 23 year-old New Yorker, Jimmy Crespo, who replaced Perry.

Schenker’s gut feeling about Tyler was correct. The singer was so deep into drugs while Aerosmith were finishing the album Night In The Ruts that he later described the experience as “like a fuckin’ solar eclipse.” But even with Perry gone, and Tyler so far gone, this album, while jokingly named, turned out to be one of Aerosmith’s very best.

A press release dated October 10, 1979 had put an end to speculation: “Joe Perry and Aerosmith announced today Perry’s plans to depart the group to purse a solo career.” The statement concluded with a barefaced lie: “His departure is described as amicable.” And while the cover for Night In The Ruts featured Perry – in a photo of the band dressed as coal miners, shot in March 1978 – any talk of reconciliation was ended on November 16, the date of the album’s release. That night, with a sense of comic timing, the guitarist’s new group, The Joe Perry Project, played their debut show at Boston College.

Six songs on Night In The Ruts had been co-written by Perry, and five featured his playing: Chiquita, Cheese Cake and Three Mile Smile, all lean-and-mean rockers in the classic Aerosmith tradition; No Surprize, the ballsy opening track, in which Tyler told the story of the band’s salad days; and Bone To Bone (Coney Island White Fish Boy), a frantic number named by Tyler after slang for a used rubber.

But in Perry’s absence, Jimmy Crespo and another guitarist, Richie Supa, gelled pretty much seamlessly with Brad Whitford. And while the album was filled out with three cover versions, they all worked brilliantly: The Yardbirds’ Think About It played at maximum overdrive, the old blues song Reefer Head Woman pulling raw emotion out of Tyler, and Remember (Walking In The Sand), a hit for 60s girl group The Shangri-Las, handled with finger-clicking panache. But in the album’s final track, a beautiful ballad named Mia, there was, as Tyler later admitted, heavy significance. “It was a lullaby I wrote on the piano for my daughter,” he said. “But the tolling bell notes at the end of the song and the end of the album sounded more like the death knell of Aerosmith for people who knew what was going on.”

In January 1980, when Night In The Ruts reached No.14 on the US chart, it seemed that Aerosmith might pull through without Joe Perry. But in the same month, when the band headed out on tour, it was heavy going. Tyler got so drunk before a show in Portland, Maine that he keeled over midway through the set, and had to be carried offstage. And even when the band had a good night, fans were still calling out for Perry, whose debut album with the Project, released in March of that year, was titled, pointedly, Let The Music Do The Talking.

Night In The Ruts was a great record, but for Aerosmith there were hard times ahead. The rot had set in. The decline was inevitable. Steven Tyler was just too proud to admit it, and too messed up to do anything about it.

Aerosmith had it all and blew it, and they had nobody else to blame but themselves. As David Krebs said: “In 1978, Aerosmith represented the living spirit of American rock’n’roll. To see them destroy themselves through immense disregard for anything but self-indulgence was a tragedy.”

Originally published in Classic Rock Presents: Aerosmith

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2005, Paul Elliott has worked for leading music titles since 1985, including Sounds, Kerrang!, MOJO and Q. He is the author of several books including the first biography of Guns N’ Roses and the autobiography of bodyguard-to-the-stars Danny Francis. He has written liner notes for classic album reissues by artists such as Def Leppard, Thin Lizzy and Kiss, and currently works as content editor for Total Guitar. He lives in Bath - of which David Coverdale recently said: “How very Roman of you!”

![Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band - Come Together [Aerosmith] (HD) - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/PgUdkvSGYGU/maxresdefault.jpg)