“I looked at drugs as a short cut to the subconscious”: an epic interview with Aerosmith’s Joe Perry

Bust-ups, brotherhood, sword attacks and the future of Aerosmith – Joe Perry looks back on 50 years in rock’n’roll

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Joe Perry is running late. This isn’t unusual behaviour for an A-list rock’n’roll musician. But the Aerosmith guitarist isn’t being a diva. It turns out his wife, Billie, found a dove with a broken leg near their Florida house and is trying to rescue it. Perry has been trying to find a box to put it in to keep it safe and calm it down.

“She’s got the touch,” he says of Billie when he arrives, apologising for the delay. “One time she found a baby rabbit up in New England, and it was nearly frozen solid. She took it inside, massaged it under warm water and brought it back to life. In another century I would have had to protect her from the people with the torches and the burning flames.”

The 72-year-old Perry wears the mantle of guitarist with one of America’s most famous, successful and occasionally combustible bands lightly. Where his Aerosmith bandmate and fellow former Toxic Twin Steven Tyler is a yapping mouth in human form, Perry is quieter, more thoughtful, even a little shy.

Things might have been different in the 70s or early 80s. Back then, Perry and his bandmates were permanently enveloped in a cloud of chemicals and had the glazed looks to prove it. But despite their enthusiasm for hard drugs and the rock’n’roll lifestyle in general, they still managed to deliver a string of stone-cold classic albums that turned excess into success: Get Your Wings, Toys In The Attic, Rocks, even Draw The Line (supposedly underwhelming but really not).

Perry quit Aerosmith in 1980, but his return four years later marked the beginning of a remarkable second act which was as successful as the first, with albums such as 1987’s Permanent Vacation, 1989’s Pump and 1993’s Get A Grip turning them into global superstars, not just American ones. If Aerosmith’s work rate has slowed down in the 21st century – just three studio albums since 2001, including the blues covers set Honkin’ On Bobo – then Perry has kept himself busy, juggling a solo career with the million-dollar supergroup Hollywood Vampires, which he founded in 2012 with Alice Cooper and Johnny Depp.

While in the background Billie pops in to tend to the stricken bird, Perry gets ready to look back on the metaphorical and literal highs of his head-spinning career. “We just wanted to make some noise,” he says of Aerosmith’s early days. They’ve done just that, and way more.

Before you took up guitar, you wanted to become a marine biologist. Why?

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Every summer we went up to the lake area in New Hampshire where my parents had a little cottage, and I just loved being in the water. I did everything I could do to spend time underwater. As a kid I used to watch [oceanographer and filmmaker] Jacques Cousteau, I wanted to be part of his team. I had a chance to meet some of the scientists at Wood’s Hole [oceanographic institute on Cape Cod near Boston] and they said: “You want to do this, that’d be great. Come back after you graduate college.” But I did not excel at school back then.

Did that have something to do with your undiagnosed ADHD?

I dunno. It just didn’t work with the way things were taught back then. I couldn’t get a passing grade to save my life, so going to college was not on the table. But I loved music, I loved rock’n’roll, the whole thing, and I felt like there was something there for me beyond being in the audience.

What made you want to play rock’n’roll rather than just listen to it?

I was always kind of an outsider at school, and I liked the idea of having a gang of outsiders. At the high-school dance you’d have all the jocks on the dancefloor, and a couple of guys on the side of the stage watching the band. That was me.

Rock’n’roll was a place I could go and nobody told me “No”. [Laughs] Except my parents. That’s why I was a late starter at taking the guitar seriously. Being a star or an idol was not on top of my list. Being on stage with other guys, playing music, that was it.

Can you recall the very first time you played on stage?

I had a band with a couple of friends. We’d been playing in our garage, doing covers – Dylan, The Byrds, that kind of thing. We played at a party, stood in corner. That was fun. The three of us kind of stumbled through the songs. The next time, we did something a little bit more electric. We had a band called Flash, and we were influenced by all the great English bands – The Beatles, the Stones. We hired the local town hall, and the ten or twenty people who were there kind of danced along and nobody left. So I thought: “This is fun.”

What did you think of Steven Tyler the first time you met him?

The first time I met him, I didn’t really meet him, so to speak. I was working in a hamburger joint in the lake area, and I did everything from cooking the French fries to sweeping the floor and taking out the trash. His family had a place up there, a bed- and-breakfast kind of thing, and every summer he’d come up from New York with one of his bands. I remember them rolling in and basically behaving like what they thought rock stars should do, which was throw food at each other. So when they left I had to clean up after them.

I kind of bumped elbows with him a few times after that. But the next summer my band with [future Aerosmith bassist] Tom Hamilton would go and play at a little club called The Barn. That’s when I formally got introduced to Steven. He’d heard that the Jeff Beck Group were looking for a new singer. A friend of ours asked if we’d be his back-up band while he did a demo.

What did you record with him?

We did I’m Down by The Beatles. He was a singing drummer – he’s an amazing drummer. And after that the two of us stayed and jammed for two or three hours. I think that’s when he saw something that I had, and of course I’d heard him with other bands. I said: “Man, we’re looking to go to Boston to form a band.” We’d hang out at parties and talk seriously about it. And he said: “Yeah, I’ll come to Boston. But I don’t want to play drums, I want to be just the singer.” And I said: “That’s good, cos we’ve got this guy from New York called Joey Kramer who is thinking about being in the band...”

You probably never thought you’d still be playing with those guys fifty years later.

Oh man, of course not. It’s amazing that we made it through those first two years. Rock’n’roll was not something you picked for career longevity. Think about all those bands that made it big, that had a big hit, then two years later they were gone. Even the Jeff Beck Group with Rod Stewart. Nobody had any inkling that it was going to be something that lasted. The whole thing was: “Don’t trust anybody over thirty.” Our vision was just to keep the calendar full for a month with gigs so we could pay the rent.

Speaking of paying the rent, in the band’s early days the Aerosmith guys all lived together in an apartment in Boston. What the hell was that like?

Tom and I got this apartment that was cheap, and we were determined to fill it with a band, which is what we did. It was a great time to live in Boston. It’s a college town and, we lived in this student ghetto. We fell right into that – same age group, only we had a different vision for what we wanted to do with our lives.

Did you get on with the neighbours?

Yeah. Our closest friend and associate was the building manager, Gary Cabozzi. He was this 250-to-300-pound ex-Vietnam vet who lived in the basement with his wife and kid. He was pretty greasy, he was missing teeth, his neck was pretty red, but he loved what we were doing. He was a big James Brown fan, and we were playing James Brown songs.

He became our guardian in the neighbourhood. There was one incident... I’m still not sure of all the real details, but there was a suitcase found outside the apartment, and someone had supposedly gone through it and put it back, and there had supposedly been a couple of thousand dollars and a couple of bags of pot in this suitcase that wasn’t there.

It’s later in the day, we’re all in the apartment, and these guys started pounding on the apartment door: “Where’s the money?” We’re shaking our heads, looking at each other, and they pulled a gun. Then this guy Gary Cabozzi came crashing through the back-stair doorway with this old sword. He said: “Motherfucker, either you use that gun or I’m gonna fucking separate your head from your shoulders.” And they backed down”.

Your first manager, Frank Connelly, was big promoter in Boston and a well- connected figure. Did you find yourself rubbing shoulders with mob guys back in the early days?

It was never said in so many words, but we got the vibe that was what was going on. Frank was the main promoter in Boston for years – he brought The Beatles to town, Hendrix, Zeppelin. He wasn’t really a manager, but he took us under his wing.

But he was also sick [with cancer] at that point. He didn’t tell us, but he knew he didn’t have long left on the planet. He’s the one that introduced us to these guys in New York, [hotshot management company] Leber Krebs: “Listen, these guys, they’re the ones that will be able to help you with your career.” He was an interesting guy, a real character. With me, he turned into a kind of father figure. I spent a lot of time at his place. He taught me a lot about life.

Aerosmith’s first two albums were both great, but they didn’t set the world on fire commercially. Was that frustrating?

It was almost like it didn’t matter. We were used to being the underdogs. The J Geils Band ruled the roost in Boston, and rightly so, and we were the young upstarts. We were from out of town, so we were never really looked at as a Boston band. We hadn’t played the clubs, we weren’t part of that whole scene. It was a while before we became part of that whole thing, and by then we were off playing around the country.

The J Geils Band were the most incredible live band I can think of, and they owned Detroit. When Detroit heard that there was another band from Boston called Aerosmith, they gave us a chance. We were bigger there than we were in Boston, and when we came back, word had spread. We playing a thousand-seat theatre and there were kids outside who couldn’t get in. I remember our manager, Frank, walking in with a pocket stuffed full of dollar bills. That was the moment when it started to feel like we weren’t pushing rope uphill.

So after the first record didn’t do what the label [CBS] wanted it to do, it didn’t really matter to us. Nothing stopped us. It was all about us playing together, feeling the band getting better, seeing the reaction from the people. That was all that mattered.

Everything changed with the third album, Toys In The Attic, in 1975, and a reissued version of your debut single Dream On. Aerosmith were suddenly huge. What was it like being in the eye of the hurricane?

We weren’t prepared for it, not at all. I remember watching Guns N’ Roses going through it. There was that summer when they went from opening up for us to being one of the biggest bands around. That’s the most exciting time for any artist, whether you’re a band or a writer, when you put out a record or a book and the fans start pulling it through.

There’s an eternal debate among Aerosmith fans: Toys In The Attic or Rocks – which is the best album?

Toys was the first time we went in the studio without a whole album’s worth of songs. We had to write some in the studio. [Producer] Jack Douglas said: “We need one more rocker.” And I sat on an amp and just started playing a riff. It was the riff to the song Toys In The Attic. That was the album where it felt like were getting some command of the studio.

With Rocks we had more confidence. We still had to write stuff on the spot, but that was the one where we had more of a handle on the creativity. Not to say that the pressure wasn’t on. We were touring constantly, we only took time off to go in the studio. No one said: “Take a month off, go write some songs.” It was like: “Go in the studio with whatever ideas you have.” That was how it was. Toys was kind of the softball album, and Rocks was the one were we felt: “Wow, we’re there.”

Sure. But which of those two albums is best?

[Laughs] Okay, Rocks seems like a more direct album. Toys, there are some high points on it, but I’d rather listen to Rocks.

You were really living up to your Toxic Twins nickname at that point. The drugs seemed to be working for you. Were they a creative aid, or did they give you confidence?

I think they did. The first time you do it, it’s like: “Oh, I’ve never felt like that, I feel like picking up my guitar...” In the early stages of whatever drug your drug of choice is, it’s a short cut to that subconscious part of you that has music or whatever talent in there that you want to access.

So when I was young, I looked at drugs as a short cut. I think there were times that they facilitated that. But that stuff, those songs, they were in there. They were going to come out one way or the other. There was a period when we were stone-cold sober for years, and we wrote some of the best stuff we’d done.

When was the point where you realised the drugs were getting in the way?

Everyone in the band arrived at that place at different times. Sometimes it takes somebody else to tell you that and hold up the mirror. I definitely reached a point where I felt they were getting in the way, but it took a lot of bad decisions and wasted times to get to that point. I remember the first thing I wrote sober, after coming out of the first rehab, was the riff to Hangman Jury [on 1987’s Permanent Vacation]. Like I said, that stuff is in there, it’s just a matter of finding that path.

You quit Aerosmith in 1979 after a backstage bust-up between some of the then-wives of the band members. What would have happened if you’d stayed in the band?

If I’d stayed in the band, the same thing would have happened. There would have had to be a dose of reality [for things to change]. I would had to have woken up sober and gone: “I need to take some time off.” We were playing stadiums, headlining all these huge shows. We could have taken a vacation, then reassembled and come back together. But we were so used to doing this tour-album-tour-album thing, it drove us into the ground.

The record company and the managers had a vested interest in us just working, working, working, cos there were plenty of bands behind us that were a little younger and a little fresher and ready to step in. Looking at our personalities and predilections for certain things, I think the best thing I could have done was leave at that point and let everything mellow out.

You put out three albums with The Joe Perry Project between 1980 and 1983. The first two, Let The Music Do The Talking and I’ve Got The Rock’N’Rolls Again, especially were great. But was it scary being out there on your own?

I really loved it. I just wanted to get out and not have the pressure of doing anything but going out and playing in a band, wherever and whenever. Listen, I missed the Aerosmith thing. My head-to-head bullshit with Steven was just that – it was bullshit. I missed the guys, I loved the guys, but there was so much clutter and so much other stuff that went along with it.

It was really tough. What I suspected – and what I heard from their mouths – was that they said: “We’re gonna step on his neck, we’re gonna starve him back to Aerosmith.” When I first left I thought it didn’t matter: “They’ll find two guys to replace me and Brad [Whitford, guitarist, who left a few months after Perry]. Steven’s the star and they’re gonna move on.” Obviously it didn’t quite happen that way.

But I was out there, just playing, having a good time. I was in a relationship in the 70s [with first wife Elyssa, who Perry divorced in 1982], so I got a chance to go out and run wild in a way that I didn’t in those early years. And I realised that it wasn’t all it cracked up to be.

You met your second wife, Billie, during that period, when she appeared in the video for your solo single Black Velvet Pants.

I was in this band in the seventies that was fucking huge, but when she met me she had no idea. She didn’t know what an ‘Aerosmith’ was, and that’s the truth. She was into the underground punk scene in Boston, she didn’t have any use for a band with a logo. The first time I took her out to dinner, my credit card came back cut in pieces and she had to pay for it. So it wasn’t about money.

The Joe Perry Project was going through another change, and somebody suggested hooking up with Alice Cooper. I went up to his manager’s house in upstate New York and we hung out for a week and worked on some songs, then he had to go off and do a movie. That fateful week I also made a few phone calls to talk to Steven. Billie said: “This band [Aerosmith] are so good, why aren’t you guys together?” And I went down the list of reasons, and I realised it was just a lot of fucking bullshit. Billie was the one who said: “Why don’t you give Steven a call. I don’t know why you guys aren’t playing together.” So I picked up the phone and called Steven. Billie called it as she saw it, and she still does. I lean on her incredibly.

Done With Mirrors was the comeback album, but it was Aerosmith’s collaboration with Run DMC on their version of Walk This Way that gave your career a shot in the arm.

I have to say, it wasn’t like we were struggling. I know looking back you can say [Walk This Way] was a resurrection, but we were still filling arenas. We didn’t have anything on the charts, but it didn’t matter. We were the underdogs again.

Did you realise how influential and important the new version of Walk This Way would be?

I wish I could say we mapped it out: “We’re gonna do this thing with rap, we’re gonna do this video where we break down the walls, we’re gonna crack open the door so black artists can get on MTV.” No, it was just about the music. We didn’t even know what the video was going to be until we started filming it. As the day went on, we realised just how powerful it could be. Sure enough, it went beyond anybody’s expectation.

Aerosmith were as big in the late eighties and early nineties as you had been in the seventies, maybe even bigger. What was different about that second act?

The hardest thing for us was working with outside songwriters. Steven and I had worked so hard together over the years, writing and coming up with tunes. The whole MTV thing and getting on the radio and whatever, it would be nice to say we did it all ourselves, but it was really exciting to let go and hearing these people who grew up listening to Aerosmith in the seventies, what their take on what an Aerosmith song could be. But nothing went out that we didn’t filter through our thing. We all did some really creative stuff.

You met Kurt Cobain when he came to an Aerosmith show in Seattle. What did you talk about?

Not much. He was pretty quiet. He just wanted to hang out. He came in the dressing room with Courtney [Love] and kind of just sat around with us. He was a normal guy. When he went off to the bathroom, Courtney – who was very verbal – said: “He loves you guys. He doesn’t like anybody, but he loves you guys.” I had nothing but respect for the guy. He was an amazing songwriter and performer, and to hear that was great.

Record companies would have you believe that the new generation hated the last generation. Like Sid Vicious saying about Keith Richards: “I wouldn’t cross the street to piss on him if he was on fire.” Meanwhile, he’s sneaking into Ron Wood’s garden house to play Keith‘s guitar [Ed’s note – it was actually Sex Pistols guitarist Steve Jones who broke into Woods’ house and stole his and Richards’ guitars]. I think I was the only guy in Aerosmith that loved the Sex Pistols. It was like: “What are you listening to that trash for? They can’t even play.”

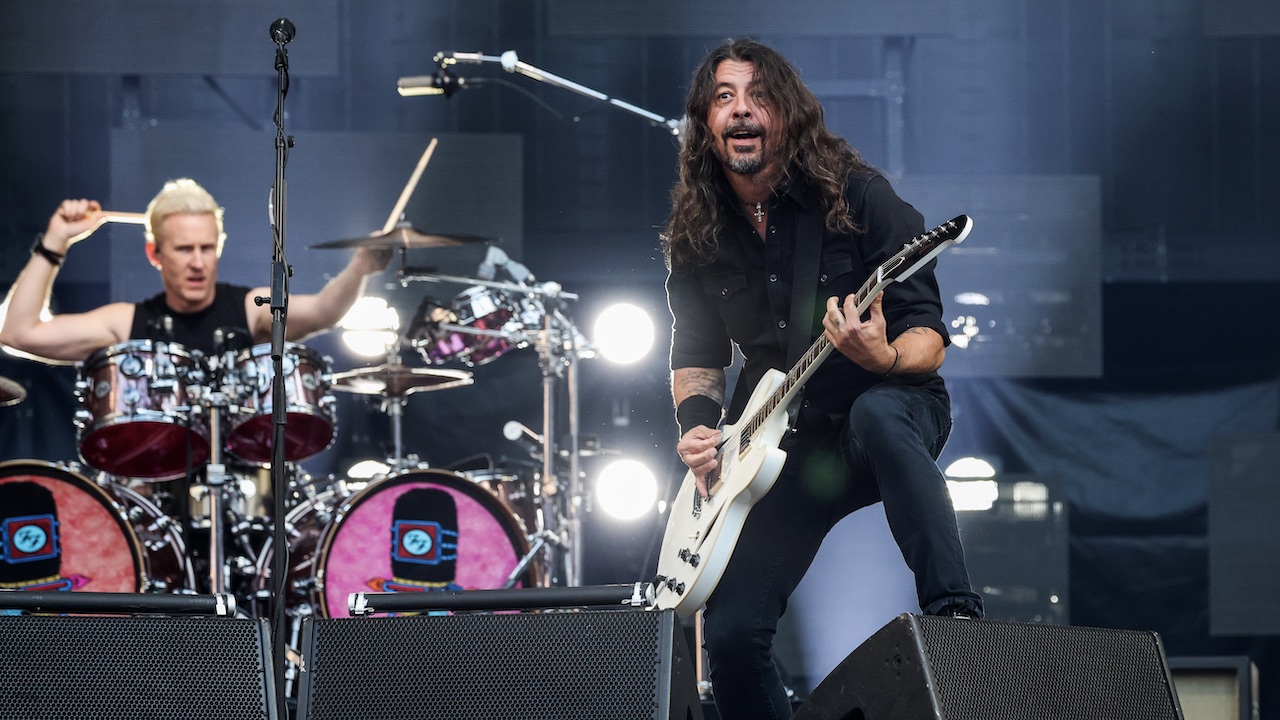

I went to see the Foo Fighters a few years ago, they asked me to come and sit in with them. They have a warm-up room where they have all the instruments set up so they can go in and jam. And they knew every Aerosmith song cold. I couldn’t believe it, I was embarrassed. They were playing songs that I hadn’t played in thirty years. There was no bullshit, they were fans, but being able to play some of those songs and know those riffs off the top of their heads, it was like: “Holy shit!”

There was an eleven-year gap between Aerosmith’s last two albums of new material, Just Push Play and Music From Another Dimension. Was that frustrating for you?

Yeah, it was a lot of time. But you’ve got to remember that we’d gone from being five of us in an apartment, to growing up and having families and kids and grandkids. There was a lot of: “I want to live life and do other things.”

When Steven was doing that TV show [American Idol, which Tyler appeared on as a judge for two seasons from 2010], it was like: “Holy shit, we’re gonna have to plan the band’s career around that.” But, god bless him, not everybody gets the chance to do that, so it was: “Go for it, man.”

There was a lot going on, so I filled it with writing. That’s why I’ve got seven or eight solo albums. I just wish some of those songs had been... I played most of that stuff to Steven.

But listen, we all had to go off and do our own thing. Not really breaking up, but there was times where everybody went off in their own direction. I wish we could have been writing and writing and writing and putting out albums, but it wasn’t meant to be.

There were tensions between Steven and the rest of the band. Do you regret doing your dirty laundry in public and putting that stuff out there?

[Laughs] Which part?

The late 2000s. Steven was jamming with Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones from Led Zeppelin, there was American Idol, he was talking about focusing on ‘Brand Tyler’. You told Classic Rock that Aerosmith were “looking for a new singer”.

I’m not sure how I feel about that. They say all press is good press, but I’m not sure I agree with that. Maybe it felt like we had to say something to our fans. Fuck, I couldn’t tell you. We were so spread apart, I don’t know. Maybe we were trying to set the record straight and be a little bit more honest and let people know what was going on. I don’t know.

How are you two getting on these days?

This is no bullshit, man, he’s probably my best friend through all of it. We just know we’re different people. Even through the seventies, we were the ones that would go off on a scuba diving trip together. In the eighties and nineties, Billie and I bought a bus so we could go out and have our kids and bring a dog with us. I remember we went out to the desert in Las Vegas with Steven. They had this truck on the big, flat desert, with a parachute thing, and we all took turns going up in this thing.

You and Billie have been together for forty years. Is it fair to say that you might not still be here today without her?

That’s more than fair to say. I have no doubt in my mind, I would not be here without my partner in life. Like I said, she didn’t know anything about Aerosmith, that was one of the things about her, so obviously there was something there beyond money and fame. We’ve been through a lot of tough times and a lot more great times. And she’s really sharp when it comes to the business stuff. I can take a guitar apart and put it back together, but when it comes to looking at a spreadsheet, I ain’t got it.

You’ve been splitting your time between Aerosmith and the Hollywood Vampires in recent years. Was it always the plan to make the Vampires a long-term thing?

We always thought of it as one-off. It was just to pay respects to the original Hollywood Vampires [the 70s celebrity drinking posse that Alice Cooper was part of] and all the people that had passed away, which was most of them. Johnny and Alice got to be friends, and they asked me to come in – I was up there at Johnny’s place. The bigger plan was to work on a solo album, but a bunch of other stuff got in the way.

Then we started talking: “What do you think about going on the road?” It’s a bunch of friends who want to hang out, except now they’re hanging out on stage and playing these songs. It’s like the ultimate garage band.

You’ve released three Joe Perry solo albums since 2005. Have you got plans to make any more?

Not right at the moment. I just don’t see the time for it. I would put everything I have into doing another Aerosmith album, if that’s even on the cards.

And is another Aerosmith album on the cards? Do you have one more record in you?

I don’t know. At this point I want to tour as much as we can. I want to get out and play to the fans. That’s really the focus right now, to get out and play live. If we get time to work on some new music, that would be great, but knowing Steven and knowing our age and what it takes to do an album... I don’t know. I’m always playing, I’m always writing stuff, but at this stage I can’t say. I just want to get through this next tour and play live and give something back to the fans.

We’ve never been the kind of band that you can sit back and go: “Well, this is what the next three years are gonna be like, this is what our next five years are going to be like.” Especially now, at our age. The air is getting thin up here, man. So many people are passing on into the next step, so to speak.

Last question. Who is America’s greatest rock’n’roll band: Aerosmith or Kiss?

[Laughing] Oh, I don’t know, man. Kiss took performance art to the next level. I remember seeing them for the first time, and I was just fucking blown away. Those guys were the best. We were fretting about not making a mistake, and they didn’t give a shit, they just put it out there. Those guys were killing it. I saw their show and thought: “What the fuck do we have to do?” I love Kiss. Kiss and Aerosmith, we’re two different entities.

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.