“I’m not gay!” How Bowie backtracked on his bisexuality for Let's Dance

In 1977, Metro’s Criminal World was considered “too gay” for the BBC. By 1983, it was too suggestive for David Bowie too

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

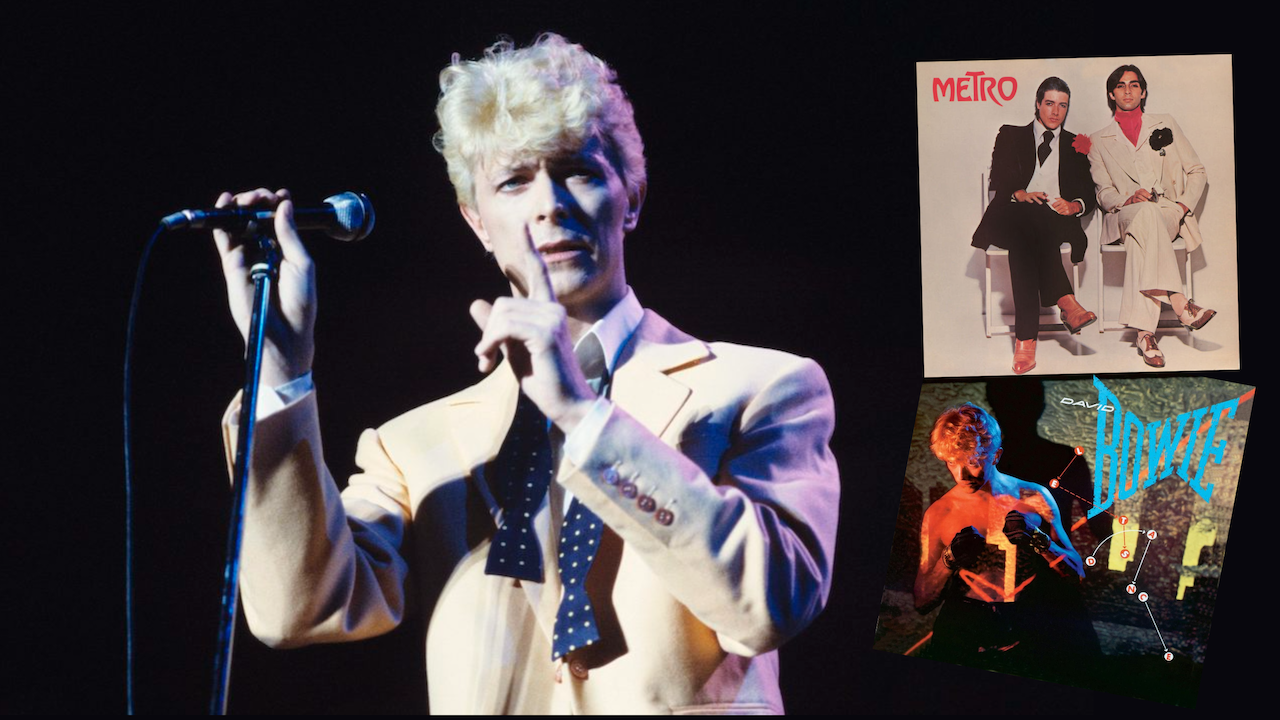

David Bowie’s Let’s Dance album was released in 1983. A collaboration with Chic’s Nile Rodgers, it was an instant success: the title track became Bowie’s only single to go no.1 in the US and UK, while the parent album went on to sell 11 million copies and turned Bowie into the international star he had wanted to be. By the end of 1983, it’s estimated that he earned around $50 million that year alone.

But the album divided Bowie fans. It had just eight songs and, of them, the title track and Cat People had already been released, China Girl was a new version of a song he'd written with Iggy Pop in 1977, and Criminal World was a cover version of another 1977 release by British band Metro – a song that had been banned by the BBC for allusions to gay sex. If it seemed tailor-made for Bowie, the changes he made to Criminal World gave us greater insight into the David Bowie of 1983 than he perhaps intended.

He had just signed a new multi-million dollar deal with EMI America and was keen to repay the faith they had shown in him. “The kind of enthusiasm they've shown is peculiar for me," he told The Face. "I mean, I’ve never had that kind of thing shown to me for years!” He talked about his older albums as sounding like historical artifacts. “I want something now,” he said, “that makes a statement in a more universal international field.”

Article continues belowIt seemed to extend to his image. The David Bowie of Let’s Dance was tanned, with a blonde quiff and dangerous white teeth, singing slick, accessible pop. He was a world away from the guy in the Ashes To Ashes video, let alone the androgynous space alien of Ziggy Stardust. Clean-cut, healthy, handsome, he seemed unambiguously hetero.

To the disappointment of many, in an interview with Rolling Stone headlined “Straight Time: No more masks or poses” he disavowed his past. “The biggest mistake I ever made [was saying] that I was bisexual,” said Bowie. “Christ, I was so young then. I was experimenting.” It was pure revisionism for a more conservative age. “He is not gay, whatever he may have blurted out in 1972,” wrote interviewer Kurt Loder, “nor was he ever a transvestite, thank you.”

On the album, the cover of Metro’s Criminal World made plain Bowie’s nervousness about his image. Metro were a British art-rock band formed in the early 70s by Peter Godwin and Duncan Browne. Influenced by Bowie, Queen and Roxy Music, they pre-dated the New Romantic scene by a few years, but had much in common with it: a modernist European sensibility that was a reaction against blues rock. Released as a single in 1977, Metro’s Criminal World had been banned by the BBC for its ‘sexual content’: allusions to cross-dressing and gay sex.

“It was considered too dark and sensual by Doreen Davis [executive producer at Radio One at the time],” says Peter Godwin (Duncan Browne died in 1993). Written in 1974, just five years after England and Wales legalised homosexual sex between men over the age of 21 (and six years before Scotland would do so), Criminal World raised a playful eyebrow at a (supposedly criminal) world where “the boys are like baby-faced girls” and “the girls are like baby-faced boys”.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

There is a suggestion of cross-dressing (“I'll take your dress and we can truck on out”) and euphemisms for blow jobs (“I know about your special kisses… I saw you kneeling at my brother's door/That was no ordinary stick-up”). Relatively tame stuff even then.

“It was a satire on androgyny, sexual ambivalence, posturing, pretending to be gay or whatever,” says Godwin. “It was just a light-hearted sort of fun exploration of what Bowie had launched when he came out as bisexual. I'm straight but I have a lot of gay friends and I'm very comfortable in a gay, or cross-gender milieu, always have been. It's always fascinated me.

"I grew up in the 60s and the first thing that happened when people grew their hair was that somebody said, ‘You look like a girl.’ So Criminal World is playing with that. There were a lot of people I saw in my circle, in my scene, in clubs, who I knew were just sort of doing it as a fashion.”

With Metro’s first album on the verge of being released in 1977, Godwin bumped into Bowie at the Embassy Club in London’s Mayfair. “Bowie was there, dancing with Bianca Jagger. And I happened to know Bianca Jagger.” Bianca introduced them and in answer to Bowie’s question about what he did for a living, Godwin explained: “I sort of do what you do, but I'm just starting out." Bowie said he’d look out for the Metro album.

Cut to 1983. “Six years later, I'm walking down the street in Earl's Court and I bumped into my neighbour Rusty Egan – of the Blitz club and Visage and so many other things – and Rusty says, 'Oh, well done about Bowie doing your track'. I said, 'What are you talking about?' And he said, 'He's done Criminal World – it's in the Melody Maker'. That's how I found out.”

He first heard the song in the company of one of his idols, Roy Harper, at the EMI office in London. Overwhelmed by the occasion he didn’t notice the lyrical changes. “It wasn’t until I got a copy of the album, I thought: he obviously thought that there was something in the metaphors of ‘kneeling in my brother's door' that was too… sleazy, you know, or transgressive. Suggestively gay.”

Bowie had changed Godwin’s original lyrics. “I’m not the queen so there’s no need to bow/I think I see beneath your make-up/I’ll take your dress and we can truck on out” was changed to “I guess I recognize your destination/I think I see beneath your make-up/What you want is sort of separation”. Metro’s later reference: “I saw you kneeling at my brother’s door/That was no ordinary stick up” was changed to “You caught me kneeling at your sister’s door.” In the words of Bowie expert Chris O’Leary, he had “turned a gay-themed line into one that Vince Neil could’ve written.”

“But ‘kneeling at your brother's door’,” says Godwin, “that could have just been voyeurism. It's all in the interpretation: you could be kneeling watching your older brother having sex. It could be anything and that's what I intended it to be. I wanted it to have more than one meaning.”

It looks like Bowie didn’t. “That's exactly what it is, isn't it?” says Godwin. “That's it.”

It wasn't even the first cover version. The year before, dance troupe Hot Gossip – best known for their appearances on The Kenny Everett Show on British TV, had released a version: they had kept Godwin's lyrics.

A generation of gay fans had felt liberated by Bowie’s claim to be bisexual a decade earlier. Now, with AIDS panic in the media and a new strain of conservatism dominating politics on both sides of the Atlantic, it started to look like a PR stunt, or like he was moving back into the closet to appease middle America.

“I hate to say it – but that timing was not probably irrelevant,” says Godwin now. ”I thought, 'He doesn't want now to be associated with something that is too gay-friendly or suggestive'. It's just imagery. I purposely made it ambiguous. It goes back and forth between men and women. I wanted it to be confusing, just like life is confusing and just like sexuality is confusing. I wanted that. It's playful more than anything else.”

“But, y’know, Elton John wasn't coming out. Even later, George Michael took a while. A lot of people in the music business were gay or at the very least bisexual, but the biggest taboo you could break in those days was to come out and say, y’know, ‘I swing both ways’.”

In 2002, Bowie admitted as much to Blender magazine: “America is a very puritanical place, and I think [being known as a bisexual] stood in the way of what I wanted to do,” he said. “I had no inclination to hold any banners or to be a representative of any type of people.”

With all those sexual ambiguities out of the way, the door to the mainstream was kicked open. It gave Godwin a boost too. There was the money that comes with having a song on a hit album (“It's not as much as people think. It didn't set me up for life, but I still make a little bit of money out of it”).

“It changed my life in a much more important way,” he says. “It gave me enormous credibility with all my fellow musicians.”

Godwin is still producing music today and is about to release a solo album as Re/Generation with US singer/songwriter Leah Lane of Rosegarden Funeral Party, a band heavily influenced by alternative 80s music. The album is preceded by a single, Beautiful Boy, and a B-Side tribute to Bowie: a widescreen cover of his 1986 song Absolute Beginners.

“It's two things: one, it's a belated thank you,” says Godwin. “Because I thank that guy eternally for the fact that he did a beautiful version of my song. And it's an homage to a guy who's gone but has left an extraordinary legacy of music. As soon as the idea was out there I thought, 'Wow, this is perfect. Yes, we have to do this'.”

The story of Let’s Dance is featured in Classic Rock issue 312 out now and available to buy directly. The Classic Rock David Bowie special is also onsale now.

Scott is the Content Director of Music at Future plc, responsible for the editorial strategy of online and print brands like Louder, Classic Rock, Metal Hammer, Prog, Guitarist, Guitar World, Guitar Player, Total Guitar etc. He was Editor in Chief of Classic Rock magazine for 10 years and Editor of Total Guitar for 4 years and has contributed to The Big Issue, Esquire and more. Scott wrote chapters for two of legendary sleeve designer Storm Thorgerson's books (For The Love Of Vinyl, 2009, and Gathering Storm, 2015). He regularly appears on Classic Rock’s podcast, The 20 Million Club, and was the writer/researcher on 2017’s Mick Ronson documentary Beside Bowie.