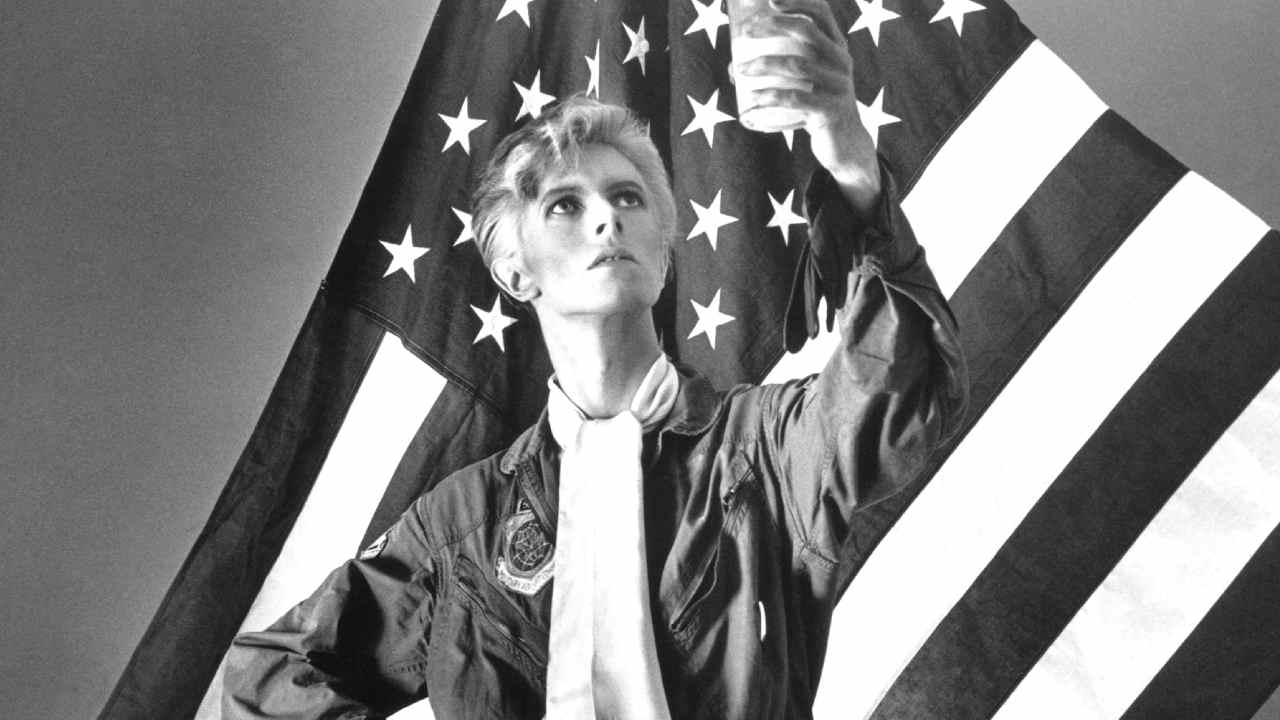

“Rock’n’roll is dead. It’s a toothless old woman. It’s really embarrassing”: how David Bowie turned his back on glam rock to make his ‘plastic soul’ masterpiece Young Americans

Drugs, madness and an ex-Beatle – the crazed story of David Bowie’s 1975 album Young Americans

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

In 1975, David Bowie was over rock’n’roll. “I’ve gone through some pretty interesting changes”, he told NME’s Andrew O’Grady. “Rock’n’roll certainly hasn’t fulfilled its original promise… it’s just become one more whirling deity, right? Going around that never-decreasing circle. Rock’n’roll is dead. It’s a toothless old woman. It’s really embarrassing.”

What he was saying wasn’t a million miles away from what punk rockers would soon shout. But this was 1975, and Bowie had become a soul man. His blue-eyed – or as he put it, “plastic” – soul switched a generation of white boys on to the joy and pain of black music. His alleged inauthenticity was of no significance. He sang it, felt it, transmitted it. The listener was moved by the result, never mind the process.

The influence of the Young Americans album, the ripples and reassessments it initiated, were to prove incalculable, irreversible. Elton John, Roxy Music and Rod Stewart soon embraced soul or disco; throughout the 80s everyone from Talking Heads and Japan to ABC and the new romantics chose this strain of Bowie as their infection. Rock may not have expired, but it knew it had to learn some new moves. Another Bowie risk, intuition, perverse gamble, had, by accident or design, paid off handsomely.

With the lurex lemon of glam rock squeezed dry, ch-ch-changes were necessary again, especially if you were the peripatetic, hyperactive Bowie. 1974’s Diamond Dogs was the last great album of that era, its epic theatrics both taking the glam ethos of delirious decadence sky-high, and wilfully razing it to the ground. Yet even there, as is often the case within the Bowie narrative, one could discern the seeds of his next chapter. 1984 had flung itself into funk rock with a hint of Isaac Hayes; Rock’n’Roll With Me was like a soul torch song turned up to 11, referencing Bill Withers’ Lean On Me. Bowie was asking himself, as the glorious song dropped from the original Young Americans tracklisting goes, Who Can I Be Now?

Lulu, of all people, played a part in Young Americans’ origin story. At sessions in New York with her, Bowie met Carlos Alomar, who he snapped up as his new band leader. Alomar had not previously been aware of Bowie. He’d been a session player at the Harlem Apollo, working with James Brown, Wilson Pickett and Chuck Berry. Bowie was a huge fan of Brown’s Live At The Apollo, and so cranked up his charm offensive to make sure he and Alomar bonded. They’d work together on 11 Bowie albums.

As the first leg of the Diamond Dogs tour was ending in July 1974, Bowie visited Sigma Sound Studios in Philadelphia, owned by Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff, founders of Philadelphia International Records, to work on tracks for Ava Cherry, by most accounts, his paramour. He was dazzled, wooed. He came away with a list of classic black albums in which to immerse himself.

Gamble and Huff, as writers and producers, were, with Thom Bell, behind the “Philly soul” sound, which updated genre tropes with disco rhythms and heavy strings. Their house band, MFSB (an acronym for Mother Father Sister Brother), a collective of over 30 musicians, had backed the label’s O’Jays, Billy Paul, Harold Melvin & The Bluenotes and The Stylistics. They’d even had a million-selling hit themselves, with The Three Degrees on vocals, with TSOP (The Sound Of Philadelphia), also the theme for TV show Soul Train. Bowie, understandably, thought it would be a terrific idea to hire MFSB as his new backing band. But even being Bowie didn’t automatically turn wishes to reality: MFSB weren’t available, with the exception of percussionist Larry Washington.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

He did however hold the winning card of Carlos Alomar. He already had sax wizard David Sanborn in his live band, but upon Alomar’s advice hired Andy Newmark, former drummer with Sly & the Family Stone, instead of Tony Newman, and Isley Brothers bassist Willie Weeks instead of Herbie Flowers. Ruthless and cold? Or decisive and visionary? Hearing that his bass-player idol Weeks was in, producer and regular Bowie collaborator Tony Visconti set off to join camp immediately. And for all these top-rank players, the master-stroke was the choice of backing vocalists as, alongside Ava Cherry, Alomar brought in his wife Robin Clark and future soul superstar Luther Vandross.

The Sigma Sound sessions began in August 1974. Bowie had to adjust to the engineers’ un-British reluctance to use effects (prior to mixing) while recording. He was hearing his own voice undressed. But things moved apace, most tracks cut live in one take, including the vocals. The album, according to Visconti, boasts “about 85 per cent live Bowie”. The star had no problem with long sessions night and day over the two weeks: his cocaine addiction was rising to a peak. It should have affected his voice. It does, but only by giving his soulful testifying extra scorch and heart. His performances are a full-throated force of nature. Justice can be flaky.

“It was self-abuse”, he told me when I interviewed him in 1999. “Drugs were not helpful in my life”. What drove him to that? “Absolutely nothing original. I just took ’em. Ha! I had lots of money, I bought ’em, and I ingested ’em. Mr. President, I did inhale. I dived in with a vengeance.”

It must have been strange being David Bowie at that time? “I wouldn’t know! I was not on this planet. I was just not aware of what was going on around me.”

A dozen or so local fans caught on and began hanging out outside the studio. Bowie liked them, and on the last day invited “the Sigma kids” in to hear rough versions. As a playback ended, there was a moment’s awkward silence until one youth shouted, “Play it again!” This time, everybody, including Bowie, got up and danced.

So productive were these sessions that numerous out-takes – from Lazer to Shilling The Rubes to a stab at Bruce Springsteen’s It’s Hard To Be A Saint In The City – didn’t make the cut (until, in most cases, later repackagings). Working titles for the whole album included, at various stages, The Gouster, Dancin’, and One Damned Song. And then came the intervention from a Beatle.

The second half of the Diamond Dogs tour became soul-centric, and in December Bowie, Alomar and Visconti reconvened at the Record Plant in New York. Win and Fascination were nailed here. Believing that was a wrap, Visconti flew to London to mix, while Bowie and in-house engineer Harry Maslin worked on other mixes in New York.

That’s when the singer met up with John Lennon, who was recording his covers album Rock’n’Roll and was enjoying, perhaps too much, his “lost weekend” phase. The illustrious pair had previously met at an LA party thrown by Elizabeth Taylor. They drank together, sang together, an excited Bowie blitzing Lennon with his new sound. With Alomar – plus guitarist Earl Slick and drummer Dennis Davis – they recorded Fame and Lennon’s Across The Universe at Electric Lady, with Maslin co-producing.

Impetuously, as the new year dawned, Bowie now insisted these collaborations with a hero had to take priority on the album. He informed an ambivalent Visconti. Who Can I Be Now? and It’s Gonna Be Me were benched. “Beautiful songs”, sighed Visconti, “and it made me sick when he decided not to use them. I think it was the personal content of the songs which he was reluctant to use, although they were so obscure I don’t think even I knew what he was on about in them.”

Certainly their mountain-ranges of melodrama were more intriguing than the overblown Beatles cover, which strains and grunts as if Bowie’s trying too hard to ingratiate himself with his new pal. “David apologised for not including me”, recalled Visconti. “There just wasn’t time to send for me. Oh well”.

Fame, however, took on a life of its own, sparking a flame, giving him a first US No.1. Based on an Alomar riff, bashed out in an evening, it was a “nasty little song” (said Bowie), aimed partly at Tony DeFries. When James Brown later sampled it for Hot, Bowie felt vindicated. It gave him North America’s seventh biggest seller of the year. Acceptance, coast to coast, for the limey weirdo.

So many elements land just right to allow the alchemy of this album. Sanborn doesn’t believe in “less is more”, but his every note swings. Vandross, co-writer of Fascination (his first published co-writing credit), was a vocal superstar in waiting. Tracks flow indulgently but the gospel-tinged call-and-response refrains keep everything tingling with gorgeous sensuality. Bowie jumps half-octaves, smashes a falsetto like he’s a Delfonic.

Young Americans, the track, for all its foggy feints at Nixon, came across to the US public, not paying much attention to the lyrics, as a celebration – we’re young! We’re American! You can, if you squint, discern the subtle influence of the rivers of rhymes which fuelled Springsteen’s first two albums, which Bowie was ingesting. “We live for just these twenty years/Do we have to die for the fifty more?” feels, however, like the kind of stunning, luckily profound throw of the poetic dice which only Bowie pulled off repeatedly in the 70s.

He was vague about the sumptuous Win: “It’s a “get up off your backside” song really…” He described Right as “a positive drone, a mantra.” As for Somebody Up There Likes Me, he touched on his dodgiest of philosophical avenues of that period. “It’s: ‘Watch out mate, Hitler’s on his way back.’ It’s your rock’n’roll sociological bit”. It’s safe to say Young Americans works better as transcendent in-the-zone pop-soul if you don’t spend too much time analysing what the then coke-addled creator said about it as it made him a transatlantic superstar. His active, irrational response was to move to LA, develop an interest in the occult, and gut and rewire these soul mannerisms, deploying them in unanticipated, counter-intuitive ways on the next album, Station To Station.

Those dropped tracks returned, correctly, on legacy reissues. Their confessional edge – is he singing about his own sex life, without misdirection? – offers a buzzy frisson. His vocals are wild, windy, winged. It’s Gonna Be Me, in particular, is extraordinary, and makes you resent the Lennon link-up. Its huge, slow, misty-blue build and stop-start arrangement support a Bowie vocal of oceanic scale: on any other album it would be the centrepiece. Maybe he felt the words portrayed – revealed? – him as a heartless womanizer. But he could have pleaded genre tropes, or being in character. Then again, “loved her before I knew her name” and other florid swoons ring of a pretty undeniable romanticism. Soul love? Love is careless in its choosing.

In 1999, with rock and roll not dead, I asked David Bowie if it had been therapeutic to sing soul. “Hmm, it was more… just another way to write,” he replied. “It added something. I still wanted to learn. I remember talking to John at the time – er, John Lennon – about people we admired, and he said, “Y’know, when I discover someone new, I tend to become that person. I want to soak myself in their stuff…” When he first found Dylan, he said he would dress like Dylan, until he understood how it worked. And that’s exactly how I feel about it… In an awkward fashion, I did that too – I lived the life, whatever it was. I’d immerse myself. Method acting? I guess it was, in a way. It comes from having an addictive personality. Transform into the thing you admire, then hopefully you absorb that knowledge – and then you move on to something else.”

“But you don’t leave it behind. I rarely did. R&B still comes through in my music. All the things I’ve been through on the way still come through”.

Which he did in 1975, his “plastic” soul having rerouted music’s march. Once again, he’d swooped like a song.

Chris Roberts has written about music, films, and art for innumerable outlets. His new book The Velvet Underground is out April 4. He has also published books on Lou Reed, Elton John, the Gothic arts, Talk Talk, Kate Moss, Scarlett Johansson, Abba, Tom Jones and others. Among his interviewees over the years have been David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Patti Smith, Debbie Harry, Bryan Ferry, Al Green, Tom Waits & Lou Reed. Born in North Wales, he lives in London.