David Bowie changed my life: the story of Earl Slick

Plucked from obscurity at 22 to replace Mick Ronson as David Bowie’s sideman guitarist, Earl Slick ’s life was never going to be quite the same again. Nor was his lifestyle

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

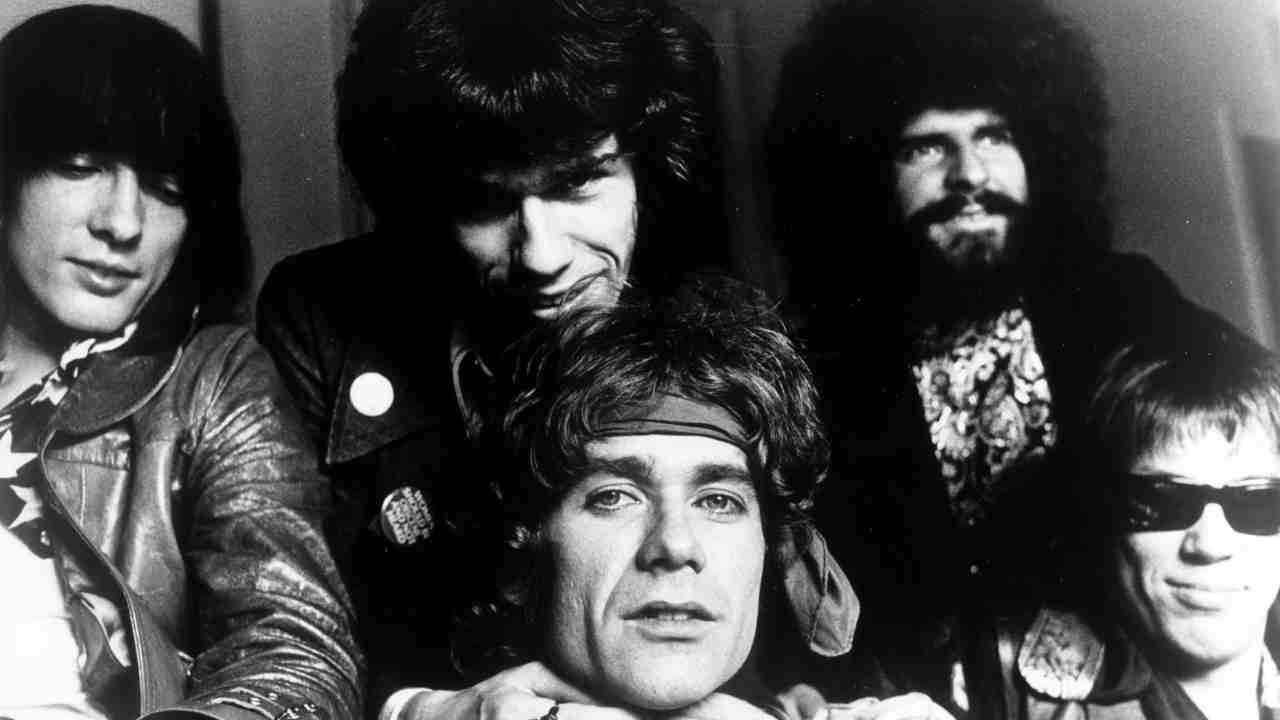

When David Bowie hired Earl Slick as guitarist for 1974’s Diamond Dogs tour, expectations were high. While Bowie’s star was cresting, Slick cut an enigmatic figure and, although virtually unknown outside of the clubs of New York City, was to replace Mick Ronson, the ultimate exemplification of the glam guitarist. Most UK fans became aware of Slick’s existence only after carefully scrutinising the cover of David Live. So who was this Earl Slick, and how did he become ennobled with such a charismatic title?

“I was about nineteen years old,” recalls whip-thin Slick today, ebony locks casually Keefed, shades indoors, plugged-in guitar nestled in lap with which he punctuates salient points, every ounce the rock star, “playing in a covers band with a singer named Jack O’Neill. We did Stones, a bunch of blues, Jimmy Reed, Muddy Waters, five nights a week, and we’d get goofy some nights. Jack would give us all weird names when he introduced us. One night he called me Earl Slick, and it stuck.”

It’s memorable, stands out on a record sleeve.

“Yeah, that’s the best thing about it, you can’t forget that one, it’s so ridiculous.”

Rock’n’roll originally came into the life of the artist formerly known as Frank Madeloni on the evening of February 9, 1964. He was 11 years old, settled in front of the family TV in Brooklyn for The Ed Sullivan Show when The Beatles changed his life.

“I was too young to get bit by the Elvis bug, but when The Beatles came on TV it really hit a nerve,” he says. “Screaming girls, cool clothes, weird haircuts, the whole thing. Within a few months I got my first guitar. The Beatles got me playing, but what kept me playing was the Stones.”

As with so many nascent rock musicians of his generation, the Rolling Stones’ repertoire provided a portal into an entirely new world of R&B, blues and soul that shaped the player that young Frank became. Before too long he hooked up with “my first real band that did gigs”, Mack Truck.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“We had two drummers and one of them, Steve Marola, played great harmonica, so me and Steve were into the real bluesy Stonesy end of things while the singer, Jimmy Mack, and the rest of them were more pop. We started playing clubs in Manhattan, had different set-lists for different clubs, and that was the start of me playing continuously.”

Playing covers in clubs was an excellent proving ground, but its appeal rapidly waned. So when opportunity came knocking, Slick was more than ready to move on.

"There was an Italian guy in the neighbourhood, Hank DeVito, who was playing with Michael Kamen, who had part of Paul Butterfield’s band with him, David Sanborn on sax. They were catching planes and playing real gigs, and I was hating playing covers. So I asked Michael if he needed another guitar player. He said no, but he did need a roadie.

"So I figured I can either stay in Staten Island, faking my way through Crosby, Stills And Nash harmony shit, or take the roadie gig and hang out with Michael Kamen, David Sanborn and Paul Butterfield’s rhythm section. So I thought I’d rather haul their gear than play that other shitty music.”

Obviously, Slick took the precaution of packing his Gibson SG.

“I’d sit in with the band during sound-check, and eventually me and David Sanborn hit it off. He suggested to Michael I should be in the band, and Michael put me in the band. I still had to haul the gear, but I didn’t mind.”

It was at this point that things took a further turn for the fairy tale. David Bowie, newly split from Mick Ronson, was in need of a guitarist, and on arrival in NYC he asked Michael Kamen (who he knew through fashion designer Ossie Clark) if he knew of any likely candidates. Consequently, Earl Slick found himself summoned for a surprisingly unorthodox audition.

“I thought it would be Bowie with a band and I’d just go in and have a play. Which wasn’t the case. I had to go to RCA’s studios where they were at the final stages of mixing Diamond Dogs. David’s assistant walked me into the main recording room. The control room was blacked out and I couldn’t see anything but the lights on the gear.

"Then a voice came on the intercom – which I later figured out was Tony Visconti – and said: ‘Put your headphones on. I’m gonna play some things, just play along.’ So I did, and that was it. After half an hour or so, Bowie walked in the room, said hello, and we chatted and noodled around on guitars for a little while. Strange.”

Strange or not, it worked. Bowie phoned the following day to tell him he’d got the gig.

"It’s funny, because I wasn’t a Bowie fan,” Slick shrugs. “I knew who he was, I owned one of his albums, Aladdin Sane, which I’d bought for Mick Ronson’s guitar. Jean Genie was right in that Chicago blues mode [Slick plays the relevant riff on the guitar that has hitherto sat silent in his lap], Panic In Detroit was completely Bo Diddley, and that’s why I bought the record. But it was the only Bowie record I had, so I went in pretty blind.”

Bowie’s Diamond Dogs/Soul tour turned out to be an ever-evolving beast. Although initially grounded in glam, it edged ever closer to R&B with every passing show, a metamorphosis that happened more by osmosis than design.

“David didn’t give any fucking direction. When it started we were promoting the Diamond Dogs record and we had that elaborate show and all that. But as we went along he started bringing in new songs to mess around with at sound-checks, and some of those songs ended up being Young Americans. Then immediately after the tour he got into that whole Philly soul thing.”

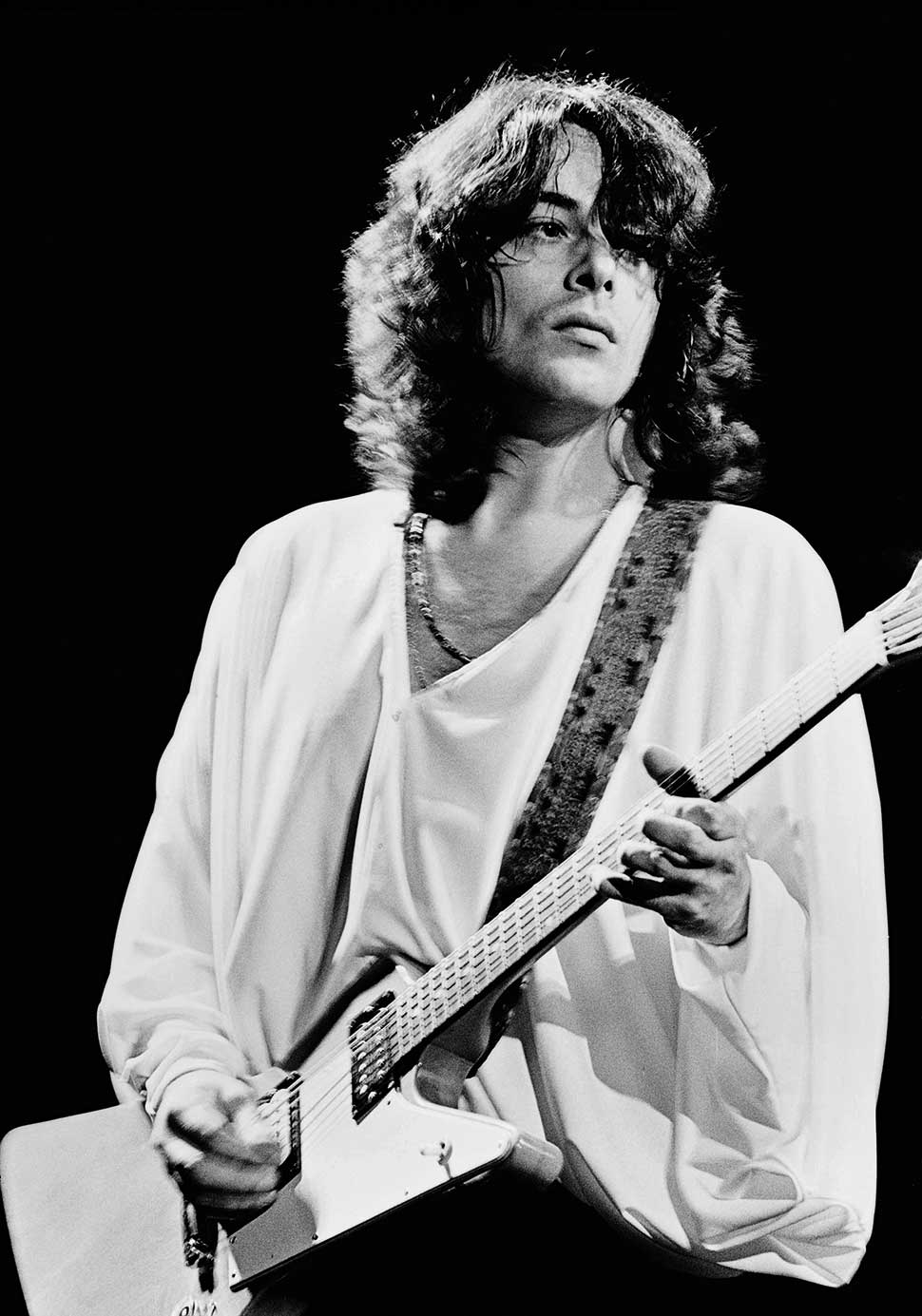

Slick went on to play on both Young Americans and Station To Station with Bowie, working alongside fellow NYC-based guitarist Carlos Alomar, a chalk-and-cheese combination that worked perfectly.

“We were as different as guitar players as a drummer would be to a piano player. While I tended toward Chicago blues – Howlin' Wolf, Muddy Waters – Carlos had worked with James Brown and R&B pop bands, so his expertise in that area was way beyond me.”

Having joined Bowie’s band at the age of 22, Slick’s life was never going to be the same again. Nor was his lifestyle. “It was like a mini-Beatlemania going on around him back then. And while I wasn’t doing anything I hadn’t done before, suddenly it was on a whole different level.”

Young Americans and Station To Station were both created in a veritable blizzard of cocaine.

“The condition we were in probably contributed more to Station To Station even than to Young Americans,” says Slick. “It fuelled a lot of experimenting and silliness we probably wouldn’t have otherwise done. I’m not suggesting you do mountains of cocaine to make a really good record, because it doesn’t normally work out very well, but for that particular record, bearing in mind we didn’t kill ourselves – which was good – it did.”

With Bowie engaged with Eno in Berlin, and Slick not required, in 1976 the guitarist released a brace of solo albums in quick succession with the Earl Slick Band. But rather than concentrate his efforts on promotion for those records, he hit the road with Ian Hunter.

“The Earl Slick Band contract came too quick and easy, and I didn’t understand that, due to the level of success I’d had with David, I was suffering entitlement issues, and didn’t appreciate what I had. There were a lot of mistakes made based on inexperience and youth. I didn’t even put together the right group of people, and I goofed up. When Earl Slick Band didn’t work out I got in touch with Ian. It’s funny, Mick [Ronson] had left, and there I was again."

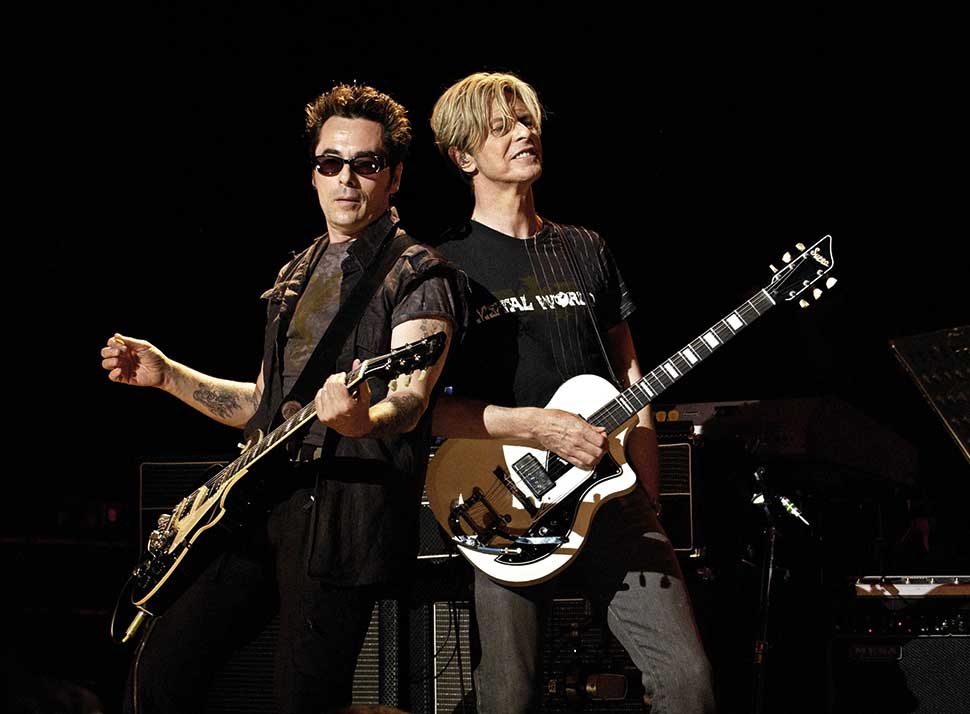

Now firmly established in the top echelon of session players, Slick worked with John Lennon and Yoko Ono, collaborating with the couple on Double Fantasy, Milk And Honey and Yoko’s Season Of Glass, before rejoining Bowie for the Serious Moonlight tour of ’83.

Ostensibly a tour in support of the Let’s Dance album, the lastminute withdrawal of Stevie Ray Vaughan (who’d played guitar on the album) and his replacement by Slick saw the tour’s set-list re-focused by necessity on Station To Station-era songs, specifically its title track and Stay (two songs that would remain Bowie show centrepieces for the remainder of his touring years).

A high-profile stint as co-founder of post-Stray Cats trio Phantom, Rocker And Slick netted a brace of US hit singles. Album releases with Dirty White Boy, Little Caesar and David Coverdale followed, prior to a return to the studio with Bowie for Heathen and Reality in the early 2000s.

Bowie even guested, alongside Robert Smith and Joe Elliott, on Slick’s 2003 solo album Zig Zag, which rather begs the question: has Slick never considered singing himself?

“It’s not me. I was talked into it a few times in the eighties, but those tapes are buried really deep.”

Following a tour with the New York Dolls, Slick was brought in to provide guitar parts for Bowie’s penultimate album, The Next Day, but there was to be no accompanying tour.

When Bowie died in January ’16, it came as a complete shock: “I didn’t know that he was sick until the news came that he was dead.”

The pair last spoke on Slick’s birthday the previous October: “He’d normally email, but this time he called. He’d never done that before, so maybe it was his way of saying goodbye.”

Aside from Earl Slick’s presence on the Bowie legacy circuit, playing Station To Station live with Stones vocalist Bernard Fowler (a project to which Bowie gave his blessing in 2015), he regularly plays alongside Glen Matlock. But at the very top of Slick’s present agenda is his imminent blues-based instrumental album Fist Full Of Devils.

“The whole album’s the soundtrack to a movie playing out in my head,” he explains. “Some of its ideas have been floating around for thirty years. It’s eclectic, but it all ties together. It’s steeped in the blues, because I love the blues the best. I’m a very blues-influenced rock guitar player. That’s who I am… That’s what I do… I’ve been up since seven o’clock and this guitar’s been in my lap ever since.”

And with that, Earl Slick riffs, noodles, and is gone.

Classic Rock’s Reviews Editor for the last 20 years, Ian stapled his first fanzine in 1977. Since misspending his youth by way of ‘research’ his work has also appeared in such publications as Metal Hammer, Prog, NME, Uncut, Kerrang!, VOX, The Face, The Guardian, Total Guitar, Guitarist, Electronic Sound, Record Collector and across the internet. Permanently buried under mountains of recorded media, ears ringing from a lifetime of gigs, he enjoys nothing more than recreationally throttling a guitar and following a baptism of punk fire has played in bands for 45 years, releasing recordings via Esoteric Antenna and Cleopatra Records.