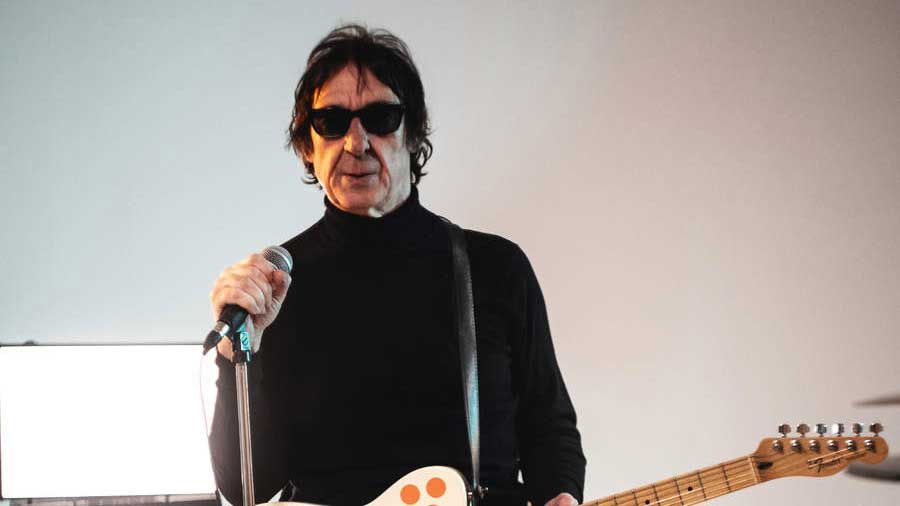

Buzzcocks' Steve Diggle: "five years of sex, drugs and rock’n’roll took its toll"

Buzzcocks' leader Steve Diggle on following his dream, the toll of partying too hard, and continuing after losing Pete Shelley

Teenage scooter enthusiast Steve Diggle was introduced to Pete Shelley by Malcolm McLaren at the Sex Pistols’ first Manchester show, in 1976, and they formed Buzzcocks, one of the punk era’s most enduring combos.

Reluctant Top Of The Pops mainstays, they enjoyed a string of timeless hits, not least the evergreen Ever Fallen In Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t’ve). Following Shelley’s tragic death in 2018, Diggle has led the band into a new era that’s soon to be defined by their first post-Pete album, Sonics In The Soul.

How did a Mancunian background shape you?

Growing up in a post-war industrial town – old Coronation Street terraces, a pub on the corner that smelt of booze and fags, factory workers – you’re trying to work out what do I make of this? But then my brother [modernist action painter Philip Diggle] was into art, and I grew up with all that sixties music – The Beatles and Bob Dylan had a massive effect on me, the Rolling Stones, Ready Steady Go!, The Kinks, The Who – and I realised there’s life outside this grimy, grainy Manchester town.

Before punk struck, who was Steve Diggle?

I was on the dole by choice. I’d one job before deciding I was going to play guitar. I put on my coat and said I’m never going to work again. I had to follow my dream. I started writing songs at seventeen, never thinking I’d be in a group, because pre-punk it seemed impossible. I mean, Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple had their names on planes. How do you get from Manchester to having your name on a plane?

What do you remember of that fateful night at Manchester’s Lesser Free Trade Hall when Malcolm McLaren introduced you to Pete Shelley and Howard Devoto?

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

A moment of fate. I’d been rehearsing with two kids, singing Paranoid by Black Sabbath, but these guys had jobs, they didn’t mean it. So I phoned a bloke in the paper and said: “I’ll meet you outside the Free Trade Hall.” And, of course, when I get there Malcolm McLaren’s standing there saying: “They’re in here, the Sex Pistols.” I said I’m not here for that. But he said: “You don’t understand, they’re in here.”

And he introduced me to Pete Shelley, who was collecting tickets. He’d spoken to somebody on the phone, and I’d phoned somebody else, so we were at cross purposes, but got on okay. So me, him and Howard Devoto sat at the back of the first Manchester Sex Pistols gig discussing forming the Buzzcocks: three-minute songs with a bit of angst, individuality and art.

Aside from the vocal melodies that brought the hits, you and Pete Shelley’s twin-guitar sound defined the Buzzcocks: tight, simple repetition.

We was all into Krautrock. All three of us went to see Can playing Manchester, just days after meeting. I had a Stockhausen box set, and recorded my mother’s vacuum cleaning once. Played it through the speakers and thought: “Wow, that noise!” So that was also in the mix. And Pete loved Neu! so there was an angular element to things as well.

You made a lot of appearances on Top Of The Pops.

At first, I was with The Clash: let’s not do it. But then I remembered seeing The Who on it when I was a kid, and thought it’d be better to be on it than not. We used to get completely drunk in the BBC bar, because I had no interest in it. I’d been playing Middlesbrough the night before to real people, rather than directors who didn’t know the music or what it was about, shouting: “Don’t look at the cameras.”

Buzzcocks made three albums, had a string of hits, but disbanded in 1981. What happened?

We partied hard, we were like Hammer Of The Gods. As soon as you signed a deal, you could afford cocaine, champagne, the lot. And we went to America a lot. You don’t conquer America, it conquers you. It was like Henry Cooper getting in the ring with Cassius Clay: only one of them was ever going to win. But at least we got in there and had a go. We had wild times in America, every night, no sleep for days, sex, drugs, rock’n’roll every inch of the way. And after five years it took its toll a bit, so we took a break.

When you lost frontman Pete Shelley, in December 2018, was there any question in your mind that you should continue with the Buzzcocks name

There’ve been a lot of band members over the years, but it was me and Pete from day one. After forty-three years it was like a marriage. We were like mountaineers, roped together: if one goes the other goes. But on the last tour, he came to my room and said: “Steve, I’m thinking of retiring. You carry on.” And I said: “You’re not leaving this thing with me.”

Then we had a break for Christmas, and when I got home I got a call from our manager: “Pete’s dead.” It was devastating. He was my brother, we grew up together. Anyway, we had the Albert Hall booked for a Buzzcocks gig, so made it a memorial for Pete with guests, but what then?

The other two guys in the band had been with us fifteen years, and it was a knee-jerk to carry on. Not just do the old hits, but usher in a new era. We’ve had the Devoto dynasty, the Shelley dynasty, now it’s the Diggle dynasty. Then came covid; I had a lot of time on my hands so started writing an album.

Was it always wine and roses with Pete?

Sometimes we’d have disagreements. Who wouldn’t? I’d call it intellectual fencing. We both liked a drink, and a lot of the people we’ve worked with would come for one or two, but we’d still be the ones there at the end. So over the years we covered a lot of ground: art, philosophy, the human condition. Pete could be quite exacting, so sometimes I’d say: “You’re too logical. Dostoevsky says logic’s like a pile of bricks – meaningless.”

Sonics In The Soul is a bold, confident statement: a tougher more contemporary spin on the familiar Buzzcocks template.

Absolutely. I’m not trying to recreate the past, I’m trying to create the future.

Classic Rock’s Reviews Editor for the last 20 years, Ian stapled his first fanzine in 1977. Since misspending his youth by way of ‘research’ his work has also appeared in such publications as Metal Hammer, Prog, NME, Uncut, Kerrang!, VOX, The Face, The Guardian, Total Guitar, Guitarist, Electronic Sound, Record Collector and across the internet. Permanently buried under mountains of recorded media, ears ringing from a lifetime of gigs, he enjoys nothing more than recreationally throttling a guitar and following a baptism of punk fire has played in bands for 45 years, releasing recordings via Esoteric Antenna and Cleopatra Records.