"The crowd was berserk, and Bruce just beaming. It was like he knew. He'd taken a massive step": Bruce Springsteen and the long road from Sunday matinees to stardom

Like many young teenagers in the 60s, Bruce Springsteen was obsessed with rock'n'roll. A decade and a lot of hard graft later, he was being hailed as its future

On the afternoon of November 18, 1975, Bruce Springsteen was being driven across West London. As he gazed out of the car window, his mood was as bleak and unsettled as the gun-grey sky shrouding the city. He was enduring an attack of nerves: that night, he was due to play his first ever show to an audience outside of America. Back home, his third album, Born To Run, released three months earlier, had been his breakthrough and was on its way to selling a million copies by the end of that year. But Springsteen’s American strongholds were still confined to his native East Coast, on down into Texas and at a last outpost in Phoenix, Arizona. Everywhere else – and most of all in his own mind – he still had it all to prove.

Prior to Born To Run achieving lift-off, he had endured six, seven years of hard labour, flogging the club and bar circuit up and down the New Jersey shoreline. He’d had periods of being penniless and destitute, and his first two albums for Columbia Records had sunk without trace. No doubt Springsteen’s iron will had been a contributory factor to the recent upswing in his fortunes, but more than that, it was the sweat-forged reputation he had made for himself as a formidable, transfixing live performer that had marked him out.

Just the previous year, his co-producer on Born To Run, Jon Landau, then working as a music writer for Boston weekly TheReal Paper, had helped to batter down doors for him. Reviewing a show that Springsteen and his freshly christened E Street Band played at the Harvard Square Theatre on May 9, 1974, Landau had written: “I saw my rock’n’roll past flash before my eyes. And I saw something else. I saw rock’n’roll future and its name is Bruce Springsteen.”

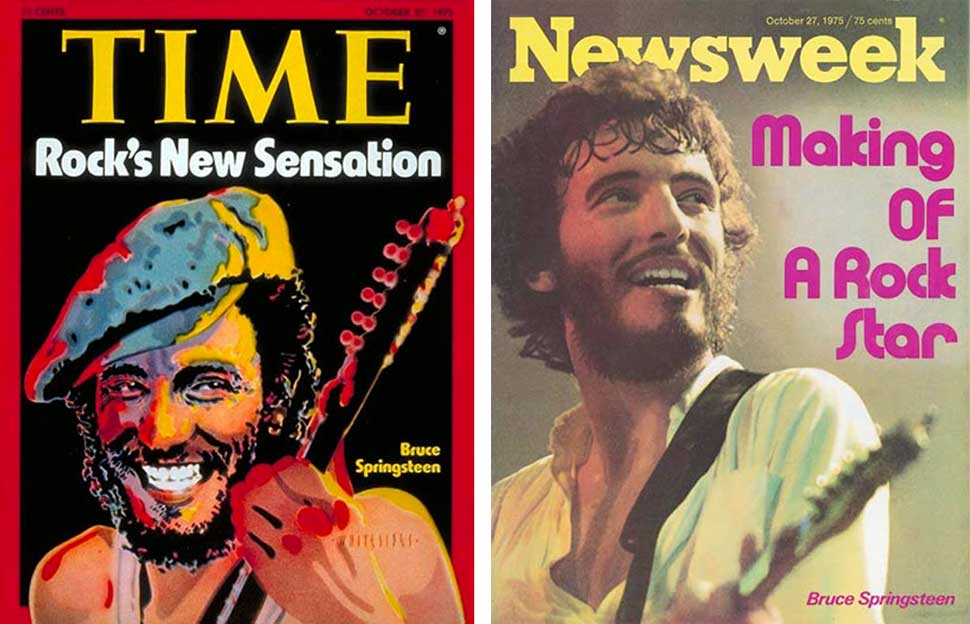

The tremors set off by that rave review had gone on rumbling ever since. Columbia Records, of course, had leapt upon it, bastardising Landau’s words to herald Springsteen as ‘the future of rock’n’roll’ in their publicity blitz for his new album. Not four weeks earlier, America’s two august news magazines, Time and Newsweek, simultaneously had him on their front covers.

Acutely, Springsteen had begun to feel as if expectations of him had been inflated to a level that was both unrealistic and beyond his control. Since arriving in London that November he’d been terse, edgy, and the scene that confronted him when his car pulled up outside Hammersmith Odeon crashed into his brittle psyche like a hammer blow.

Hung across the Odeon’s marquee in feet-high red lettering were the words: ‘Finally! London is ready for Bruce Springsteen’. Scowling, the scrawny, unprepossessing 25-year-old Springsteen, a woollen hat pulled down over his unkempt hair, skulked inside the venue. There he found much the same message emblazoned on posters and also the handbills that had been placed on each of the Odeon’s 3,500 seats.

“The kiss of death!” Springsteen wrote in his autobiography. “I’m frightened and I’m pissed, really pissed. This is not how it works. I know how it works. I’ve done it. Play and shut up. My business is show business and that’s the business of showing and not telling!”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Springsteen snapped. In a rage, he stomped about the Odeon, charging up the stairs and down the aisles, tearing posters from walls and ripping handbills to confetti. It was a purging, but it left him feeling unbalanced, unsure of himself, and when he took to the stage at a sold-out Odeon that night, he was fighting a war in his head.

“We go on,” he wrote. “The audience seems reticent, the room feels uneasy. That’s my responsibility… I am in and out of myself for a while in a most unpleasant way. I can feel myself caring too much, thinking too much.

“At the time I found the evening so disconcerting that I never viewed the concert film until 2004. When I did, I found out… it was a great document of the band performing in all its disco-suited, leather-jacketed, knit-hatted mid-70s glory.”

On the night, almost everyone else had an altogether different view of this wired, wiry visitor from Freehold. And in time Springsteen would himself settle more comfortably into the new, larger-than-life character that he would have to become. Also, hard-won experience would give him a firmer grip on the mighty forces he was able to command on stage.

For now, though, and for all the miles he had already then travelled, he was still just fitting into his own skin, shaking the dust from off his shoes and getting ready for the last-chance power drive he was about to take to a distant horizon, to where greatness and even possible immortality might lie.

Part One: Jersey Boy

“All I saw when I was a kid was showmen. The doo-wop guys, Sam & Dave – these people who believed the show was a tool of communication. It was a joy, and part of the fun was getting dressed up in your suit, going on and doing some clowning, some preaching, making the band so tight and knocking the songs into one another with such a furious pace that the audience couldn’t catch their breath. You left them exhausted and exhilarated.” – Bruce Springsteen to me, April 2009.

The first time Springsteen played to a paying audience was in 1964, at the Freehold Elks Club. He was not yet 16 and, armed with the electric guitar and amp he’d sold his pool table to buy, had joined a group of other fresh-faced kids from the neighbourhood in a fledgling band they called The Rogues. That debut at Elks was a Sunday matinee show for local teenagers. The Rogues played for free, and Springsteen sang their centrepiece song Twist And Shout that he’d just heard The Beatles doing.

Born into a blue-collar family and raised in the then economically impoverished borough of Freehold, Springsteen had first got the rock’n’roll bug after seeing Elvis Presley on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1956. Right then he’d begged his mum to get him a guitar, an acoustic. He got one. Eight years later The Beatles arrived in America like beings from outer space.

“In 1964, there were no more magical words in the English language [than The] Beatles,” Springsteen wrote. “It didn’t take me long to figure out. I didn’t want to meet The Beatles. I wanted to be The Beatles.”

It wouldn’t be through The Rogues. The others kicked him out of the band soon after their Elks turn. Unbowed, Springsteen holed up in his bedroom for the next several months and taught himself to play lead guitar. He got good enough to sail through an audition for another, more proficient local group, The Castilles. A typical three-chord garage group of the period, they fashioned their covers set around The Beatles, Stones and other British Invasion bands such as The Who and The Kinks, with a smattering of Motown and R&B standards thrown in.

The Castilles played at high-school dances, ice-rinks, cook-outs, basically anywhere and to anyone that would have them. It was their other guitarist, a strikingly good-looking lad called George Theiss, who sang lead vocals. Springsteen noted later: “I was considered toxic at the microphone.”

Through various line-up changes, The Castilles soldiered on until August 1968. By then they were going in ever diminishing circles, and anyway a new musical wind had begun to blow in from across the Atlantic. A tougher, stranger brew, this soon supplanted the beat-group sound, and was summoned up by emerging guitar heroes such as Jimi Hendrix and his Experience, Eric Clapton in Cream, and Jeff Beck. Springsteen got himself a second-hand Gibson and bent with the times.

“When I plugged it into my Danelectro amp, magic!” he wrote. “The thick, chunky sound of Clapton’s psychedelic-painted SG came ripping out of me… and I was transported into another league.”

Earlier on in that spring of 1968, a new club had opened up above a shoe shop just 15 miles east of Freehold in downtown Asbury Park, right out on the Shore. The Upstage Club was equipped with a full-throttle PA and stayed open after hours for ad-hoc jam sessions. It very quickly became a haven for the Shore’s emerging community of young musicians.

Among the regulars were a wildlooking drummer called Vini Lopez and three other teenagers who would become inexorably tied to Springsteen: Danny Federici, Garry Tallent and an extrovert, motor-mouthed character in the habit of sporting an outsized polka-dot tie that stretched from his neck to the floor, named Steven Van Zandt. As an out-of-towner, Springsteen arrived at the Upstage as an unknown quantity, but he soon made an impression demonstrating his ability to nail Clapton and Beck’s licks.

Following the demise of The Castilles and fresh out of high school, he formed a new band, Earth. A power trio along with two more Upstage regulars, bassist John Graham and drummer Michael Burke, they played around the clubs and bars, doing Hendrix and Cream tunes, until February 1969. At which point Springsteen brought together Lopez, organist Federici and former Castilles bassist Vinny Roslin (later to be replaced by Van Zandt) in a new outfit, initially named Child and then, when they discovered another band had taken that name, Steel Mill.

In this latest incarnation, Springsteen started to write his first songs, which were of a crunching, sprawling, Allman Brothers-inspired type. Steel Mill also acquired a manager of sorts, Carl West. A transplanted Californian, West otherwise designed surfboards and was commonly known as ‘Tinker’ on account of his ability to fix anything mechanical. Tinker had the vision at least to extend his new charges’ boundaries from New Jersey south into nearby Virginia.

By the end of ’69, and in spite of not having a record to their name, Steel Mill had built up enough of a following in their adopted state to draw 3,000 people to their semi-regular concerts in Richmond, while back in Jersey they’d opened up for such heavyweights as Grand Funk Railroad and Iron Butterfly.

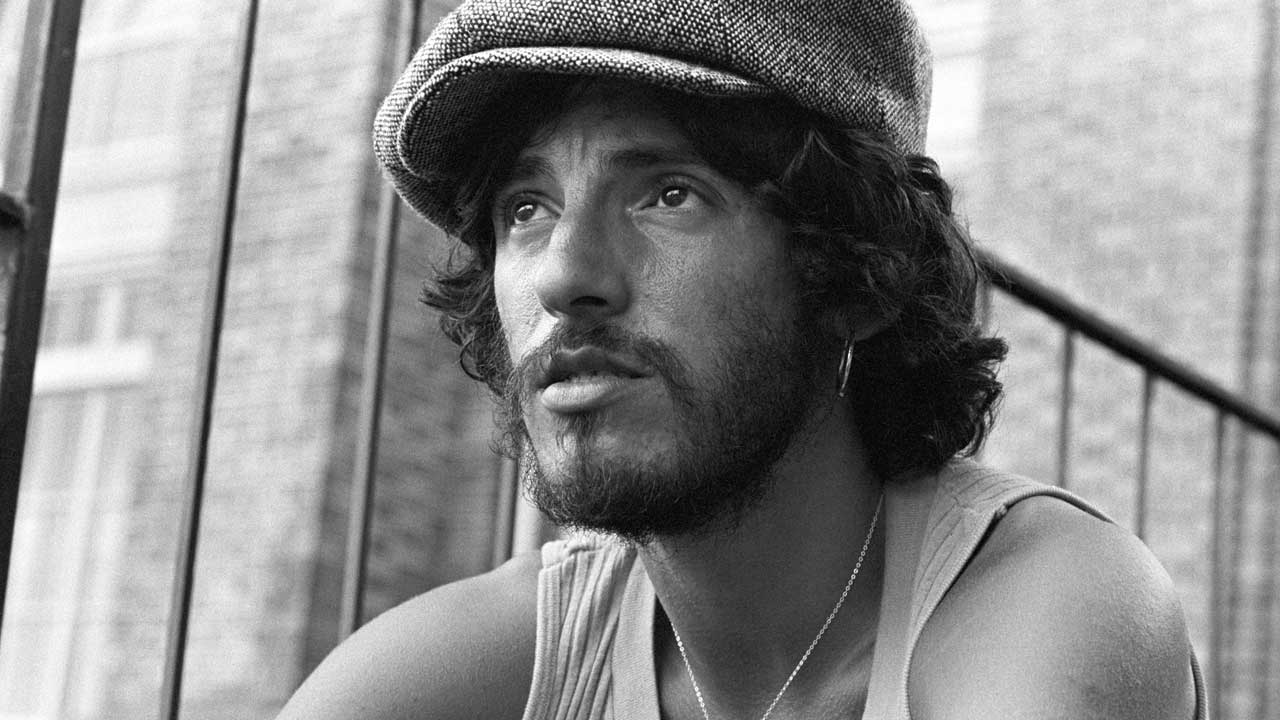

At this point, Springsteen’s parents had moved cross-country to America’s West Coast so his father might find work. Bruce had had to move out of the family home and into West’s surfboard factory to skimp on rent. During the intervening period he had also grown up. From being a shy, pimpled adolescent, he now had long hair, a streaky frame and a hawkish handsomeness As Steel Mill burgeoned, he became a more overt performer too.

From having stood stock-still, eyes trained often as not on the floor, now he came out of himself and took centre stage. Recalling a transformative show at the University of Richmond on November 20, 1969, West’s lieutenant, Billy Alexander, told Springsteen biographer Peter Ames Carlin: “The crowd was berserk, and Bruce just beaming. It was like he knew. He’d taken a massive step.”

Steel Mill were getting paid up to 500 dollars a night on their stints around Virginia’s college auditoriums and gymnasiums, and they were home-town heroes too. But they were big fish in a small pool. They could play three, four times a year in each state, but no more for risk of exhausting demand. West told them he had connections on the psych-rock scene in San Francisco. So, convinced, and on the cusp of a new decade, they crammed into his Ford flatbed and Federici’s station wagon and made the three-day, non-stop drive to California in search of fresh pastures.

When they got there they slept on the living room floor of Springsteen’s parents’ small San Mateo apartment and auditioned for gigs. In part they were successful. They scored a Tuesday night slot at venerable promoter Bill Graham’s starred Fillmore West in downtown San Francisco. Graham also funded a demo session, but ultimately nothing came of it. But such was the plethora of bands fighting for a slice of the Haight-Asbury action, Steel Mill weren’t able to make ends meet. Back East they went, tails between legs. More significantly, and having sized up the competition, Springsteen resolved that from now on he would need to do things differently.

“I was fast but, like the old gunslingers knew, there’s always somebody faster,” he wrote. “I would have to push myself harder, work with more intensity than the next guy just to survive untended in the world I lived in.”

For Steel Mill, the clock was running down. Springsteen made another visit out West to see his parents for Christmas 1970 and into the New Year. On the local FM station, he heard Joe Cocker’s big-band live album Mad Dogs & Englishmen, and Van Morrison’s similarly ordained His Band And The Street Choir. Obsessing over these twin melanges of robust horns, slick R&B grooves and folk-rock roots, he had found his way forward.

Part Two: Blinded By The Light

“I used to collect hotel room keys. Back in the day when we stayed in little Holiday Inns and they had plastic room keys. I stuck them on a piece of leather and occasionally I’d look through them to see where I’d been.” – Bruce Springsteen to me, April 2009.

Back in Jersey in January 1971, Springsteen disbanded Steel Mill. He next moved quickly to assemble for himself the sort of multifaceted band that Morrison had and that Leon Russell had put together for Cocker. Out also went any pretence Springsteen might have had towards democracy.

The Bruce Springsteen Band incorporated the talents of Van Zandt, Lopez and Tallent, plus David Sancious, a prodigiously gifted 16-year-old pianist whom Springsteen had happened across at the Upstage. Bulked out to a 10-piece by a horn section and a pair of girl backing singers, they debuted at Brookdale Community College in Lincroft, New Jersey on July 10, 1971. The very next night the played a gig opening for Humble Pie at the Shoreline. Altogether, this was Springsteen planting the seeds for his future music and the E Street Band.

“Everybody talks now about the Jersey sound,” Lopez told writer Dave Marsh in 2006. “Well, that’s the beginning of it – the change from Steel Mill to that band, with the horns. Nobody did that before – maybe they had a sax player, but not a horn section.”

“I wanted to incorporate the values of those old showmen,” Springsteen told me. “From the beginning, we were a rock and soul band.”

The disadvantage of this unwieldy set-up quickly became apparent. That autumn, the Bruce Springsteen Band returned to Steel Mill’s old Richmond stomping grounds. But the cost of transport, meals and additional hotel rooms for their extra numbers made it all but impossible for them to make the kind of money they’d made before. Springsteen decided to trim the group back to the core five-piece for their club and bar gigs, and save the horns and backing singers for showpiece events.

In September, the quintet began a residency at Asbury Park club the Student Prince that ended up stretching to the end of ’71. On the first night the place was near-empty, with just 15 paying punters at most. But in another early indicator of Springsteen’s career trajectory, the gig mushroomed through word of mouth.

“The second week, we played to 30 music lovers,” Springsteen recalled in his book. “The week after that it was 80, then 125. We started playing Fridays and Saturdays, then Wednesdays too – five 55-minute sets from 9pm to 3am and we were drawing 150 people, the club maximum We’d charge one dollar at the door and take the receipts. We were making a living.”

One dark, stormy Jersey night, a tenor sax player called Clarence Clemons went along to the Student Prince to size up the band. Clemons had his own gig at the opposite end of Asbury Park, and had previously played alongside Garry Tallent in an R&B group. Standing well over six-feet tall and built like the side of a house, Clemons could be relied upon to make an impression. And that evening was no exception.

“As the Big Man approached the front of the Prince,” Springsteen eulogised, “a mighty gale blew down Ocean Avenue, ripping the door of its hinges and down the street. A good omen.”

Clemons asked Springsteen if he could sit in with his band, and “a tune that sounded like a force of nature poured out of his horn… My immediate response was that this was the sound I’d been looking for.”

Clemons wasn’t ready to give up his own steady gig, though. In any case, Springsteen was about to meet someone else who would have a more immediate and defining impact on his life. It was Tinker West who introduced him to Mike Appel. A livewire, fast-talking 30-year-old, Appel had been raised in the genteel environs of Long Island’s North Shore. Like Springsteen, he had grown up obsessing over music and was then working at a Brill Building-style songwriting ‘factory’. Springsteen played Appel a bunch of the songs he had written. Appel wasn’t bowled over.

This only served to spur Springsteen on. During his now annual jaunt out to his family in California that Christmas, he wrote up a storm. By the time he got back East he had written at least five new tunes. Among these were two – It’s Hard To Be A Saint In The City and Growin’ Up – that simmered with the same folk-soul tension he’d discovered in Van Morrison and with lyrics that showed off a new-found sense of vivid street poetry. When Appel heard these he became animated, convinced he’d stumbled upon a new Dylan.

In short order, Appel quit his job and, with a business partner, Jimmy Cretecos, set up a management company, Laurel Canyon Productions, which in March 1972 signed Springsteen as a solo artist. Up until then, Springsteen had been living hand to mouth and didn’t even have a bank account. He signed the contract that Appel’s lawyer had drawn up for him sight unseen. Ultimately it would be the ruin of the Appel and Springsteen’s relationship.

“We would split everything 50-50,” Springsteen noted more than 40 years later, adding sardonically: “The problem would be all the expenses would end up coming out of my half.”

It was nevertheless true that Appel crusaded tirelessly on Springsteen’s behalf. He hustled to get him auditions with Atlantic Records and Columbia. Atlantic passed. But on May 2, 1972, Springsteen sat down with an acoustic guitar in the Manhattan office of Columbia’s legendary A&R chief John Hammond and played for him the same songs he had played for Appel. Hammond was the man who had brought both Bob Dylan and Aretha Franklin to the label. Now he snapped up Springsteen.

Within a couple of months, Springsteen and his band were holed up in 914 Studios in Blauvelt, a leafy hamlet 45 minutes outside Manhattan, recording his debut album, to be titled Greetings From Asbury Park, NJ. The result was an album of densely layered, intricate songs such as Blinded By The Light and Lost In The Flood, on which he was backed by Tallent, Lopez, Sancious and also Clemons.

Sancious cried off the tour to push the record, in order to work on his own music, so Springsteen brought back Federici. To begin with, their focus was on the East Coast clubs and small theatres, but Appel also booked them to play a one-off show for the convicts at Sing Sing prison in upstate New York. Springsteen drew roaring applause that day when he announced over the mic: “When this is over, you can all go home.”

In the main, life was a slog. The whole band were travelling in Lopez’s dilapidated car, and they were each making about 35 dollars a week. Also, depressingly, the album had sold barely 20,000 copies. Along the way they opened for the Eagles, Chuck Berry and Jackson Browne, and in spring ’73 did a fraught two-week stint in arenas with the horn-fuelled Chicago, who then had a US No.1 album under their belt.

Springsteen and his band had already been tagged ‘house wreckers’, which is to say the kind of show-stealing band that no one would want to have to follow on stage. After two nights opening for Chicago, Springsteen’s access to the headliners’ PA and video screens was cut. He seethed off the tour, swearing to Appel that he would soon be done being anyone’s warm-up act.

Springsteen’s contract with Columbia stipulated that he deliver them a new album every six months. In between live dates, he and his band, joined again by Sancious, went back into 914 Studios and made the record that gave the group their name: The Wild, The Innocent & The E Street Shuffle. Overall, the album was the closest Springsteen would get to realising his Van Morrison fixation. A shape-shifting musical gumbo, it had just seven songs, but they were richly detailed and reeled between lilting piano and pulsating horns, rock stomp and R&B groove, and all that at the same time in standout track Rosalita.

Lopez, so volatile a personality that Springsteen had nicknamed him Mad Dog, didn’t see out the sessions. One evening, he got into an altercation with the band’s tour manager, Steve Appel, Mike Appel’s kid brother, and swung a punch. Springsteen fired him on the spot. In his place came a friend of Sancious, Ernest ‘Boom’ Carter, a more disciplined, harder-driving drummer. Carter’s effect on the band was instant. Dave Marsh wrote: “The E Street Band of April ’73 played Van Morrison-style arrangements well. The E Street Band of August 1974 blazed its own path – it became a unique rock band.”

Out on the road, Springsteen and the E Street Band were waging a war of attrition. They went back to the same cities time and again, and on each occasion played to bigger, more responsive audiences. As ringleader, the once nearmute Springsteen had also begun to open up to audiences, spinning yarns and comic fables to introduce key songs in the set, building his own mythology. Yet still this didn’t translate into record sales. Columbia had by then signed Billy Joel, an easier artist than Springsteen for them to sell, and The Wild, The Innocent & The E Street Shuffle went largely untended and unnoticed.

On May 9, 1974, Springsteen and the E Street Band arrived at the Harvard Square Theatre in Cambridge, Massachusetts. They were there to play two shows: a matinee and a late-night set opening up for blues woman Bonnie Raitt. During both sets, Springsteen introduced two new songs that he had written and begun demo-ing up in Blauvelt that January.

Each was representative of a new wall of sound going on in his head, of roaring hot-rod engines and soaring crescendos, and charted a classic rock’n’soul course between Roy Orbison’s keening balladry, Duane Eddy’s stinging guitar and the epic surge of Phil Spector’s 60s productions. The songs might have been still-skeleton versions of Born To Run and Jungleland, but they knocked back the watching Jon Landau. The rest would soon be history.

Part Three: Thunder Road

“It’s like you have to go the whole way because… that’s what keeps everything real. There’s a morality to the show and it’s very strict. Everything counts. Every individual in the crowd counts – to me. What I always feel is that I don’t like to let people that have supported me down. I don’t like to let myself down.” – Springsteen to Dave Marsh of Rolling Stone, August 1978.

The sessions for Born To Run at New York’s Record Plant studio were drawn-out, tortuous affairs as Springsteen painstakingly pieced together its eight songs. As with both of the two previous records, the album was begun with Appel as producer. But as fruitless months went by, Springsteen brought in Landau to help him realise his grand vision.

The E Street Band had also gone through changes. Sancious had left for good to make a solo album, taking Carter with him. To take their places, in came two seasoned veterans of Broadway pit bands: Roy Bittan, a virtuoso pianist, and another propulsive drummer, Max Weinberg. Steve Van Zandt, meanwhile, effectively talked himself back into Springsteen’s employ.

Dropping by the studio one night, Van Zandt was aghast to find Springsteen, Landau and Appel labouring over the horn parts to Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out. Van Zandt intervened and fixed the arrangement for them in minutes. Afterwards, a delighted Springsteen instructed Appel: “Let’s get this boy on the payroll.”

In the end, Born To Run took more than a year to complete. With it finally on the launch pad, Springsteen and the E Street Band played a five-night, 10-show residency at West Village club The Bottom Line. By then the title track was already burning up American radio and the word on Springsteen was truly out. Robert De Niro, Martin Scorsese and Lou Reed were among the Bottom Line audiences that watched rapt as Springsteen went at each relentless 90-minute set with his eyes burning and like a man wanting to take on the world.

“Waiting for the crowd to be let in that first night,” Dave Marsh wrote later, “you felt you were about to attend some kind of coronation.”

Two weeks after its release on August 25, 1975, Born To Run vaulted into the US Top 10. Having begun on August 21 with a three-night stand at the Electric Ballroom in Atlanta, Georgia, Springsteen and the E Street Band were already off criss-crossing the States. With a smash album at last to buoy them, their sets expanded to take in six of the Born To Run songs and up to half a dozen more covers of rock and R&B standards. As the tour wound on and into bigger theatres and auditoriums, they were playing for so long that Springsteen was even able to dispense with having an opening act.

Testing his and the band’s limits, he played around with running orders and arrangements on a nightly basis and also leaned even more towards putting on a show. In this regard, it was Clemons who became his sparring partner and comic foil. Up there side by side, the two of them now brought Born To Run’s instantly iconic cover shot to technicolour life.

“Clarence was a figure out of a rock’n’roll storybook, one perhaps I’ve partially authored,” Springsteen wrote. “Previous to 1975, he often hung at his microphone. One night I walked up to him and said that would no longer be good enough. We could use our musical and visual presence to tell a story only hinted at in my songs. We could live it… [and] Clarence knew instinctively what to do.”

It was at the midpoint of the tour that they arrived in London. After the uncertainties of the first Hammersmith show, following dates in Stockholm and Amsterdam they returned for another go at the Odeon on November 24. Unlike before, on this occasion Springsteen was not beset by doubts. As he wrote later: “We played a blaze of a show that left us feeling there might be a place for us after all amongst our hallowed young forefathers.”

The tour ran on until the next spring, finishing on May 28, 1976. Altogether, it had been both a reckoning and a triumph for Springsteen. Not that he was able to enjoy the afterglow from it for long. Almost as soon as he was off the road, he began a long and bitter legal dispute with Appel over the terms of the original contract he’d signed with him. It would drag on deep into the next year, with Appel serving a counter-suit that prevented Springsteen from recording.

To earn money as much as for any other reason, Springsteen took the E Street Band off on a 54-date charge around the States, acidly christened the Lawsuit Tour. However, by the start of 1977, money was so tight that band members had to take IOUs in lieu of a pay cheque. The legal case was finally settled that spring, and work began straight away on a new record.

When Darkness On The Edge Of Town eventually emerged on June 2, 1978, it seemed that Springsteen had channelled reserves of rancour, desperation and bitterness into it. Its 10 songs were the most potent he had yet written, but nothing like as approachable and embracing as those on its predecessor. The album won rave reviews and followed Born To Run into the Top 10 in the US, but it soon stalled.

Ticket sales for the tour were also slow. Springsteen had moved up to sports arenas, but venues such as the 17,000-capacity Riverfront Coliseum in Cincinnati were often scarcely a third full for his shows. But this adversity fired Springsteen to push himself more fiercely, as though on a mission to cement his place in the musical firmament. Kicking off with Darkness’s urgent opening song, Badlands, and built around the new album, the shows were exercises in raw intensity and commitment.

With their backs to the wall again, Springsteen brought the E Street Band out fighting. In all they went at a frenzied, unyielding pace for seven months and 115 shows, and without leaving America. Sure enough, he clawed back lost ground. Over five consecutive nights from August 18, 1978, they played two sold-out shows at the cavernous Spectrum arena in Philadelphia and three more at New York’s Madison Square Garden. By the last date, on New Year’s Day 1979, he was bloodied – and literally, when a firecracker thrown from the audience opened a cut over his eye – but able to claim that a notable victory had been won.

Also, the Darkness tour was symbolic in staking out the terms by which he would from then on engage as a performer. Early on during it, Landau became his manager, enabling and encouraging Springsteen’s purest artistic instincts and setting him up for the long haul. Through it he established the vast scope of his shows, playing for three hours and more, with a short intermission to let both band and audience catch their breath. Overall it bore witness to the moment that the idealised image that Springsteen had aimed at for himself, his music and his band took on solid, permanent form.

“The performers that I loved were the guys who were willing to take their moment on,” he told me in 2009. “The band is an entertainment organisation. We put on a show, you know? We have an emotional manifesto that we approach the audience with. And we try to put something together that when you walk out at the end of the night, you go: ‘Wow!’”

Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band's 2024 world tour kicks in Phoenix on March 19. Tickets are on sale now.

Paul Rees been a professional writer and journalist for more than 20 years. He was Editor-in-Chief of the music magazines Q and Kerrang! for a total of 13 years and during that period interviewed everyone from Sir Paul McCartney, Madonna and Bruce Springsteen to Noel Gallagher, Adele and Take That. His work has also been published in the Sunday Times, the Telegraph, the Independent, the Evening Standard, the Sunday Express, Classic Rock, Outdoor Fitness, When Saturday Comes and a range of international periodicals.