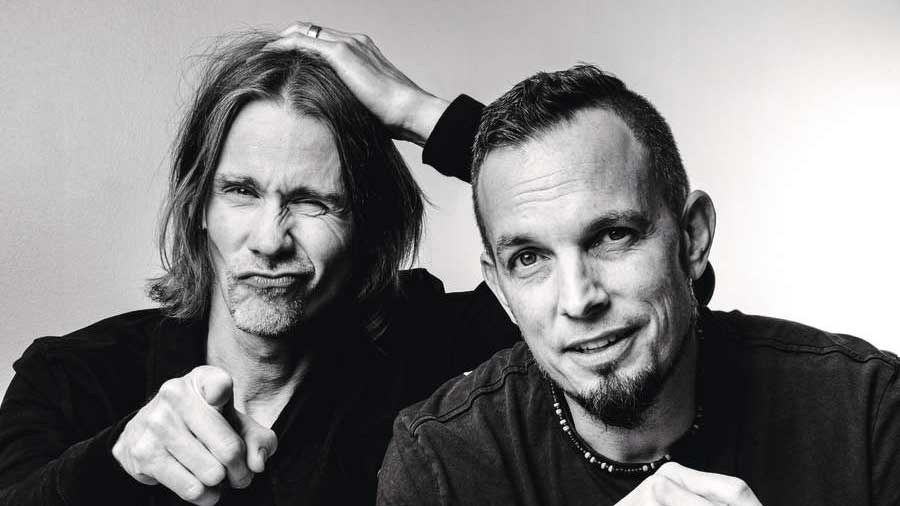

Alter Bridge: "I told myself the dream was over many, many, many times"

Myles Kennedy and Mark Tremonti are living proof that you don’t have to be an asshole to sell loads of records, pack arenas and be a rock star in 2022

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

They say you never forget your first time. And the broad smile that creases Myles Kennedy’s ruggedly handsome face as fragmented recollections of a red-letter day coalesce and come into focus rather telegraphs his subsequent admission that he treasures the memory as a transformative moment in his life. A practised, unhurried storyteller, he leans forward to sketch out the scene with broad strokes. It’s 1984, and in Spokane, Washington, Alter Bridge’s future frontman – at this point a 14-year-old schoolboy – is set to perform in front of an audience for the first time.

“My friends and I had formed an ‘air’ band, and we’d told everyone that we were going to play a gig without any instruments,” Kennedy explains. “We set up in the church pianist’s basement, and our parents thought it was going to be really cute, so everyone was like: ‘Let’s go downstairs and watch the kids play!’”

At the appointed hour, Kennedy’s step-father, a minister in the Methodist church, invited his congregation to join him for a very special musical performance. Descending into the basement, the unsuspecting churchgoers were greeted by a demonic cacophony that Satan himself might have considered ‘a bit much’ when selecting his walk-on music for Judgement Day.

The passing of time has done nothing to dull Kennedy’s gleeful memory of what happened next, as he watched familiar smiling faces darken in confusion, horror and disgust.

“What they didn’t realise was that our set-list featured only full-on metal,” he explains. “Shout At The Devil, Screaming For Vengeance, Iron Maiden… It took literally two songs to clear the entire room. It was wonderful.”

To his eternal credit, pastor Kennedy took the prank in good humour, and sustained only minor damage to his reputation in the local community. Known simply as Glenn to the two boys he raised as his own following the untimely death of their father Richard Bass, his laid-back, supportive approach to parenting will forever make him a “hero” in the eyes of Myles Kennedy. But when, during a family camping trip the following year, the teenager raised the prospect of a second ‘air band’ performance, the minister, mindful of the boy’s growing obsession with the music of Van Halen, Def Leppard and Led Zeppelin, proposed he take on a new challenge.

“I remember he was building a fire, but he stopped, turned around to look at me, and said: ‘Son, why don’t you learn how to play for real?’” Kennedy recalls. “From that moment, my life had a purpose.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“And fast forward almost forty years,” he says, raising his hands, palms outstretched, like a magician who’s just pulled off a particularly mesmerising illusion, “here we are.”

As fabulously succinct as this first-hand account of Kennedy’s musical journey is, we’d be doing Alter Bridge’s 52-year-old frontman a grave disservice by wrapping up the story at this point. Because when he proclaims the epic title track of his band’s new album Pawns & Kings “a battle-cry for the underdog”, urging ‘Don’t let the bastards grind you down’, this is not the empty posturing of a performative rock’n’roll entertainer, but a heart-felt sentiment born of lived experience, wisdom gained from years of hurt, frustration and disappointment chasing his dreams.

When a disillusioned, burnt out, bruised and weary Kennedy tried to quit the music business 20 years ago after recording a second album with the Mayfield Four – records a trusted friend later admitting to feeling “uncomfortable” listening to, given Kennedy’s compulsion to lay bare unvarnished truths – it was an act of self-sabotage as much as self-care, a decision that went against every fibre of his being.

“It’s a brutal business, brutal,” he admits. “But no matter how bad my heart would break, I just couldn’t stop. I kept getting back on the horse, like a dumb-ass. I told myself the dream was over many, many, many times, but I couldn’t let go, because I understood the power of music. So finally I walked away [laughs]. And that didn’t work out either!”

This, obviously, is a little joke. Today, in the bar of an upscale West London hotel, Kennedy and the man who fucked up his early retirement plan, his co-pilot in Alter Bridge, bullet-headed 48-year-old guitarist Mark Tremonti, will hold court until darkness falls, for a steady procession of print, online and broadcast media journalists eager to learn the stories behind Pawns & Kings, the band’s seventh studio album, released in October on Berlin-based label Napalm Records.

A little subdued and slow to spark following a decidedly less than restful, jet-lag-impacted first night in the UK, the pair, both clad head to toe in regulation black, are nonetheless attentive, gracious and professionally charming in their early-afternoon interactions with each representative of the media, as per their reputations as two of rock’s ‘good guys’.

“You got me at a good time,” Kennedy says with a gentle smile as he settles himself on a sofa, the first of the pair to do so. “I’m so tired that I’ll just blurt out everything, and get myself in trouble.”

We both know this won’t happen. In truth, if we’re laying our cards on the table here, almost everyone involved in today’s polite and polished promotional dance – Kennedy, Tremonti, Alter Bridge’s long-time manager Tim, hovering discreetly at all times, their UK PR team, and all but the most green, fresh-faced media reps – knows that the two musicians don’t really need to be here today.

Alter Bridge are not, and never will be, rent-a-quote press darlings. And given the loyalty of their impressively dedicated fan base, the commercial success of Pawns & Kings, in the UK at least, will fluctuate only by small margins irrespective of the weight, reach or range of whatever pre-release promo activity is listed on today’s schedule. Which isn’t to say that Tremonti is being anything but entirely sincere when he says that days such as today play a pivotal role in raising awareness of Alter Bridge’s follow-up to 2019’s Walk The Sky.

“We want to make the most of this record,” he states, “as the last one got destroyed by covid, touring-wise.”

One can’t help feeling that he and Kennedy could spend every allotted minute of their media ‘face time’ on anything they wanted to and Pawns & Kings would still debut in the UK Top 10, just as each of the four studio albums they released in the last decade – 2010’s AB III (chart peak No.9), 2013’s Fortress (No.6), 2016’s The Last Hero (No.3) and the aforementioned Walk The Sky (No.4) – did. Because this is the standard level at which the Florida-based quartet, arguably the most reliable and trusted blue-chip, arena-filling hard rock act on the circuit, now operate.

Factor in projected sales of more than 90,000 tickets for the band’s winter British and Irish tour (which commenced on December 5 at Nottingham’s 10,000-capacity Motorpoint Arena, and wound up a week later at London’s 20,000-capacity O2 Arena) and it’s clear that in the eighteenth year of their career Alter Bridge are A Big Fucking Deal.

And yet the traditional peripheral indicators that accompany this level of success are almost entirely absent here. There are no paparazzi skulking near the hotel’s revolving doors, no Alter Bridge loyalists camped in the shrubbery in the hope of grabbing selfies to get Instagram fanpages popping, no hotel residents interrupting our conversation to ask for an autograph.

As the hotel bar fills up, fellow guests curious as to the duo’s identity might peg the long-haired Kennedy as a ‘creative’, a painter perhaps, or a photographer, or imagine the tattoo-and piercings-free Tremonti to be here for an interview for a security job or evening bar shifts. This anonymity, in these surroundings at least, is a sweet spot that suits Kennedy, Tremonti and their absent bandmates Brian Marshall and Scott Phillips just fine, thank you very much.

“Do I want world domination with Alter Bridge?” Myles Kennedy asks aloud. “Thanks, but no. Because I see the complications that it brings into people’s worlds. This is the best place for us to be.

“My brother and I sometimes talk about this, actually. He’ll say to me: ‘Do you realise how lucky you are? You can go anywhere, eat anywhere, shop anywhere, without being recognised or getting bothered, and then you can go play music to an arena full of people. You have the best of both worlds!’

“For me, this altitude is a beautiful place in which to fly,” he says, smiling again. “And honestly, I wouldn’t trade it for the world.”

At an unspecified point in his late 20s/early 30s, a time when even fewer people knew his face or his name, Kennedy woke up to the realisation that like-minded souls in his orbit were “disappearing”.

“Losing friends to addiction was a real wake-up call for me,” he reflects, his gratitude evident. “It came at a time when I was starting to change, hanging out with the wrong crowd, falling into those rock’n’roll clichés. Playing music, from my first band Bittersweet onwards, I discovered that all those temptations laid bare in [infamous book that detailed Led Zeppelin’s excess all areas] Hammer Of The Gods were freely available even if you weren’t in Led Zeppelin. Luckily, before darkness descended I met the woman who would become my wife, and changed my ways, telling myself let’s not go down that road. But in different circumstances? Sure, I could have fallen for all that craziness.”

With the practised caution of a seasoned world traveller anticipating regular border checks in his near future, when asked to declare which specific ‘recreational’ vices might have impacted hardest upon his health and happiness during his deepest immersion in rock’n’roll cliches, Kennedy smiles, shrugs and says: “I plead the Fifth [Amendment] on that.”

It’s no secret that the Seattle rock scene of the early-to-mid-90s was awash with heroin; Mother Love Bone’s Andrew Wood and Alice In Chains’ Layne Staley just two of its high-profile casualties. And while Spokane’s less-celebrated artistic community never succumbed wholesale to its dark, intoxicating ‘glamour’, as a younger man Kennedy wasn’t blind to the ready availability, and indeed allure, of certain illegal narcotics.

“There were drugs around,” he acknowledges, “and for me there was an experimental phase with that. But I definitely realised that this would be something that would most definitely get in the way of me being creative. What I saw with drugs was people being fooled into believing they were being more creative than they were. When I was lucid, I’d watch that, and think: ‘You’re fooling yourself.’ I never imagined drugs would bring out the best in me.

“Which is not to say that I don’t understand their use. The other day, my wife, who’s a massive Depeche Mode fan, watched the concert documentary [101] they shot in the late eighties as they were travelling across America. At one point, [frontman] Dave Gahan was asked if he was happy. And he replied saying something to the effect of: ‘Yeah. But I was also happy when I was working at a grocery store.’ The pressure of being a frontman every night can be so overwhelming. And then it makes total sense why some guys get hooked on drugs and alcohol, or face the mental health issues that arise from this lifestyle. It’s a tricky dance if you don’t want to end up another rock’n’roll statistic.”

Mark Tremonti knows this as well as anyone. As a beaten-down Myles Kennedy was pulling the plug on The Mayfield Four, Tremonti, was wrestling with an altogether different, although no less brutal, Big Life Decision: whether or not to walk away from America’s then-biggest rock band, Creed, which he’s poured his heart and soul into for the best part of 10 years.

Creed’s phenomenal success had already far outstripped the most outlandish, fantastical dreams the teenage Tremonti ever entertained while honing his guitar chops beneath the Metallica and Slayer and Iron Maiden posters on his bedroom walls.

Remarkable, then, that revised in 2022 Creed’s sales figures in the US alone are almost incomprehensible: between 1997 and their break-up in 2004, the Tallahassee, Florida band sold 28 million albums, and their second and third – 1999’s Human Clay and 2001’s Weathered – both debuted at No.1 on the Billboard 200 chart.

By 2002, however, the relationship between Tremonti and Creed vocalist Scott Stapp was so damaged, in part due to Stapp’s escalating issues with alcohol abuse and cocaine addiction, that the guitarist couldn’t stand a single second in Stapp’s company. Even now there’s anger in Tremonti’s voice when he revisits memories of a dream turned sour.

“I’ve had jobs that were shit,” he says, “terrible jobs that I hated showing up for, but this was different. When you have this passion you’ve had your whole life, and you achieve the kind of huge success you always dreamt of, but you have this factor that’s tearing it apart, that’s destroying your whole life, it’s the most heart-wrenching, terrible thing. And I resented it. As a kid I could not imagine being in a successful band that was not fun to be in.

"But it got to the point where every other week Scott Phillips was quitting and I was begging him to stay, or I was quitting and he was begging me to stay. And then one day we both wanted to quit, and that was it. We had to think about what would really make us happy: making another platinum record with a band you hated being a part of, or being an artist and chasing new dreams. We felt we’d earned the right to be happy.”

Level headed, good humoured and personable, Tremonti comes across as a thoroughly decent human being, with an inner steel underpinning a calm, composed character. You sense he’d make a good brother-in-law, and you’d definitely want him on your side in a fight.

It perhaps surprising, then, to hear him say that he still feels like an outsider – not wholly comfortable in either rock’n’roll circles or ‘normal’ life. “I don’t think I’m some cool badass, and I’d feel like a pretentious asshole calling myself a rock star.”

At his lowest ebb, he wasn’t about to let Scott Stapp destroy his dreams, so he went in search of a singer who was the exact opposite of his egotistic, arrogant, confrontational former bandmate, personality-wise. Which is when he approached “the nicest guy we knew” with an offer to start a new band, to take a leap of faith without knowing where it might take them.

As a kid, growing up in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, the guitarist was taught by his parents to fear only one thing: the city six blocks from their family home, just down Alter Road.

“I was constantly told: ‘Do not cross that street!” Tremonti recalls. “Where we lived was a vision of suburbia, whereas Detroit, to my parents, was drugs, crime, depravity, danger. It was not nice, it was not safe. Growing up, Alter Road, to me, represented the unknown. And in walking away from Creed, from everything we knew, we had to cross into the unknown again. So that was the start of Alter Bridge.”

Tremonti and Kennedy use the same word to describe how they view music: the word ‘magic’. But no one waved a magic wand to lift Alter Bridge into the elevated realm in which they exist in 2022 – a fact that the hard-working Tremonti, now with 17 albums to his name, is quick to stress.

“Alter Bridge has been a fight from day one,” he says. “Everything we’ve achieved with this band, we’ve earned it. We had a lot of proving to do, a lot of negative energy to overcome.”

For Kennedy, by his own admission, some of that negativity came from within. Growing up on a farm, shovelling horse shit as he listened to the greatest rock albums of the 70s and 80s, he knew he could never be a golden god like Robert Plant, a showman like Freddie Mercury, a fearless boundary breaker like David Bowie.

And when he first heard David Lee Roth, still the archetype for rock’n’roll frontmen, singing Van Halen’s take on The Kinks classic You Really Got Me, he was rendered speechless: “I remember thinking: ‘Wow! It sounds like he’s having sex in outer space.’”

And while Seattle’s grunge explosion offered reassurance that rock music could be made by guys who looked, thought and lived like Kennedy did, a part of him always felt that he had to be more than Myles Kennedy, bigger than Myles Kennedy, louder than Myles Kennedy in order to make it. “I was watching a rock’n’roll documentary recently where a music writer said something, referring to frontmen and that larger-than-life rock-star persona, which really stuck with me. He said: ‘People don’t pay to see the humble bumble.’ And I get that. That kind of swagger is entertaining and compelling, and I love to watch people who have it.”

Now, when he looks back on his early years with Alter Bridge, Kennedy remembers an uncertain, anxious introvert trying to pull off a decent impression of a rock star.

“I tried and I tried, but I could never quite find that persona,” he says. “And looking back, it’s embarrassing. I felt like an imposter, and I felt like people knew it too, like they were looking at me thinking: ‘This guy is bullshitting me.’ They maybe didn’t believe in me as a rock star, because I didn’t believe in me either.”

Kennedy remembers the exact point at which he gave up pretending to be someone else, and embraced, and started to rather like, who he is. And once again the catalyst for change came after a conversation with his step-father Glenn, backstage after a 2014 show with his side hustle, fronting Slash & The Conspirators.

“We were opening for Aerosmith,” he recalls, “and it was one of the first shows I played with Slash in front of my parents, so I was kinda operating with that rock guy persona. Then after the show I’m hanging out, and my step-dad pulled me aside and said: ‘You know, just don’t forget who you are.’ And man, that was an important moment for me. Because at that point I realised: ‘You know what, I’m just gonna be me up there, and if people like it, great, if they don’t that’s fine too. And since I started doing that, I finally felt comfortable in my skin.”

It’s at this point that I suggest, perhaps a little rudely, that when the name Alter Bridge is raised in music industry circles, the words “such lovely, genuine guys…” is often followed by a pause, an embarrassed shuffle of feet, a lowering of the voice, and a somewhat apologetic “…but kinda boring”.

To their credit, on hearing this, Kennedy and Tremonti both laugh out loud.

“Look,” says Kennedy, “I totally get that. And if I didn’t know me and didn’t have to live in my shoes, I’d probably say the same thing. But for people that do embrace what we do, I think that’s part of the allure: that we are more – for lack of a better word – pedestrian, that we don’t have that swagger. But to pretend to be anything other than who we are would take so much energy, would be so exhausting day after day.”

“If you want to make it in music, you better have a thick skin, because people aren’t slow to tell you what they think of you,” Tremonti says with a shrug that suggests he’s not losing sleep about anyone’s perception of him or his band. “We are who we are.”

The guitarist is silent for a moment, perhaps considering whether or not to share a story that cuts to the heart of why Alter Bridge is important to him, and why this band and their music is important to so many others. In the end, he takes the plunge. He recalls a meet-and-greet session with fans, when a young couple shuffled forward, both crying, overcome with emotion.

“Meet-and-greets aren’t the best situations in which to have a proper conversation,” he admits, “and it was a little awkward for all of us. But we talked, and they relaxed a little, and then they pulled out a photograph. They told me that they’d lost a child, and showed me the photo, which showed the child’s gravestone, which featured our lyrics.

"That’s the power that music can have in someone’s life. So it’s important to me that what we do is real. When people have our lyrics tattooed on their skin, or in that case, carved in stone, you don’t want to betray their trust in you, and turn into a clown.”

“When this is all over, and I look back on what Alter Bridge was, I’ll be able to tell my grandkids that we stayed true to ourselves,” Tremonti concludes. “We didn’t put on costumes, we didn’t fake it; we fought, and we survived. And we made music that was honest, and that mattered, to us and to our fans. Whatever happens with this album, and however our lives unfold from this point on, that will be enough for me.”

Pawns & Kings is out now via Napalm Records.

A music writer since 1993, formerly Editor of Kerrang! and Planet Rock magazine (RIP), Paul Brannigan is a Contributing Editor to Louder. Having previously written books on Lemmy, Dave Grohl (the Sunday Times best-seller This Is A Call) and Metallica (Birth School Metallica Death, co-authored with Ian Winwood), his Eddie Van Halen biography (Eruption in the UK, Unchained in the US) emerged in 2021. He has written for Rolling Stone, Mojo and Q, hung out with Fugazi at Dischord House, flown on Ozzy Osbourne's private jet, played Angus Young's Gibson SG, and interviewed everyone from Aerosmith and Beastie Boys to Young Gods and ZZ Top. Born in the North of Ireland, Brannigan lives in North London and supports The Arsenal.