Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

A bitterly cold January afternoon in New York, 1979: a top-level meeting at the headquarters of Atlantic Records on Rockefeller Plaza. Present are company president Jerry Greenberg, the label’s head of A&R Michael Kleffner and AC/DC manager Michael Browning. Subject under discussion: the abject failure of AC/DC to crack the American market, and what to do about it.

Despite their initial success at home in Australia and subsequent career lift-off in Britain and Europe, no AC/DC album had gained any traction whatsoever in America. One of them – 1976’s Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap – wasn’t even released there. Worse still, their recent live album, If You Want Blood You’ve Got It, which Atlantic had banked on “doing a Kiss” – breaking a band with a great live act but zero visibility on mainstream radio, the way Alive! had for Simmons and co. – had been a disaster sales-wise.

Which is why Browning had been summoned to Atlantic HQ for what he describes today as “the discussions”. Maybe it was the singer, suggested Greenberg, not for the first time. Maybe he didn’t have the right voice for American radio. Maybe they would do better with someone else? “Not in a blunt ‘either do it or we drop you’ type way,” says Browning now. “But there was that kind of conversation going on.”

When the manager refused to relent about Bon, it was Kleffner’s turn to chip in. Maybe the band needed a new producer, said the A&R man. Studio svengalis Harry Vanda and George Young had helped steer the band this far, but perhaps they had done all they could. The problem was that not only were Vanda and Young still in the production hotseat, but George Young was the elder brother of AC/DC guitarists Malcolm and Angus Young. It was a family business. In the Atlantic boardroom, Michael Browning weighed up the options.

“It was obvious something had to be done,” he says. “George had been fabulous for them but he hadn’t been to America for years, and American FM radio had a sound you had to experience to really understand.”

The meeting ended with the three men agreeing that AC/DC needed a new producer to crack America. A week later, Michael Kleffner flew to Sydney to break the news to George Young: if he really cared about his brothers and their band, he would have to step aside as producer. George didn’t take the news well, but Kleffner was adamant: for Atlantic to continue investing in AC/DC’s future, they needed new blood with them in the studio. Grudgingly, George Young agreed to step down.

So it was in early 1979 that the wheels were set in motion – albeit with no little friction – for what would prove to be the most pivotal year of AC/DC’s career, and for the album that would change their destiny: Highway To Hell.

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

Even as he was speaking to George Young, Michael Kleffner had a replacement producer in mind: Eddie Kramer. Within a week of their conversation, the latter was on a plane to Sydney to began work with AC/DC.

The 36-year-old Kramer was no novice, having previously worked with Jimi Hendrix, Led Zeppelin and Kiss, but the sessions were doomed from the start. With all three Young brothers still fuming at George’s unexpected ejection and Kramer’s subsequent appointment by the suits in New York, AC/DC were ready to go to war. The situation wasn’t helped by an upturn in Bon Scott’s drinking. Always heavy, it had become excessive even by his standards.

“I went there,” says Kramer, “hung out with them, tried to do some demos, and realised that there was an obvious difficulty with the singer too. He had the most incredible voice, but trying to keep him in check from his drinking was a very tough call. But I think more than anything, the band resented me being foisted onto them. It was like sticking a pin into them.”

When Kramer insisted that the band decamp to his regular studio in Miami, the resentment grew. The producer’s task was undermined further by the fact that Malcolm and Angus were allegedly sending demo tapes to George back in Australia behind Kramer’s back, which the elder Young would critique – negatively.

After a series of increasingly angry phone calls from Malcolm, in which the guitarist threatened bloodshed if Kramer wasn’t fired, Browning realised he needed to make a drastic change, and quickly. He had another producer in mind – 31-year-old hotshot Mutt Lange, who had recently produced the Boomtown Rats’ No.1 hit, I Don’t Like Mondays. Browning approached his manager, Clive Calder, to ask if Lange would be interested in working with AC/DC. “Clive was going, ‘No, no. they haven’t got a big enough base’,” he says. “But I just hammered them and by the end of the night I called Malcolm back and said: ‘It’s cool, I’ve got Mutt Lange’. He said: ‘Who’s he?’.”

Though neither Browning nor the Young brothers could have known it, it was to be a game-changing decision for all involved. Born in Mufulira, Northern Rhodesia – now Zambia – in November 1948, Robert John Lange was a middle-class kid who made his name as a guitarist on neighbouring South Africa’s miniaturised music scene, before stepping behind the mixing desk. As a producer, he was a perfectionist, noted for making musicians play their parts countless times until they got things absolutely right. It was a world away from AC/DC’s no-fuss approach. When the two parties met each other at a pre-production rehearsal in London in March 1979, neither side knew or, frankly, cared much about the other.

“Mutt turns up with a mop of curly hair and green wellies on, and they’re all going to me, ‘Who the fuck’s that?’,” recalls Ian Jeffery, AC/DC’s tour manager at the time.

If Lange had been apprised of the situation vis-a-vis George Young, he showed no sign. All the Young brothers knew of Lange was what Michael Browning had told them: that he was “a genius” – the sort of smarmy introduction that had them both curling their lips. Malcolm later joked that if he’d known their new producer was then enjoying his first major UK chart success with the Boomtown Rats, “we’d never have let him through the door.”

These initial suspicions didn’t stop the band and their new producer from knuckling down to work. Basic tracking began in earnest on AC/DC’s new album on Saturday March 24 at Roundhouse Studios in Chalk Farm, North London, with all of the recording completed exactly three weeks later, on April 14.

The first track they worked on was Highway To Hell itself. The instantly arresting guitar-drum intro had been demoed with just Angus grinding away on guitar while Malcolm bashed at the drums. All was nearly lost when an engineer took the only cassette of it home, where his young son playfully unravelled it. Fortunately, Bon, who was always rewinding his own worn-out cassettes, put it back together the following day and the tune that was about to transform all their lives was restored.

The fact that the intro sounded like Free’s All Right Now was not lost on Lange, who hired Free’s old engineer Tony Platt to help him mix the final edits. “He was looking for someone that would give it that kind of dry, punchy rock thing,” says Platt now. “That feeling of time and space.”

It was a sound that characterised the whole album. Tracks like Touch Too Much – retrieved from a flailing, earlier incarnation and remade into a top-notch toe-tapper – and the pulsing Get It Hot were, on the surface, cornerstone heavy rockers, yet, as Platt points out, they had proper groove. Even the scorching If You Want Blood (You’ve Got It) was impossible to listen to without moving yourself out of your seat. “One of Mutt’s things that he brought to AC/DC was how to really work a groove,” he says. “They may have been an out-and-out rock band but you could now dance to their tunes.”

George Young had always encouraged his charges to simply give it their best shot and damn such niceties as tuning and time-keeping, but Lange insisted on everything being in perfect balance, melodically, rhythmically and harmonically, so when each song exploded into action, it did so against a backdrop that contrasted rather than competed for attention.

In this way, he even coaxed from them tracks that took their foot off the pedal long enough to almost be called ballads. In the case of Love Hungry Man, the beat was essentially no different to Highway To Hell, but the idea was much less in-your-face (although Malcolm and Angus came to see it as a bridge too far, refusing even to play it live). With the final track, Night Prowler, Lange even took them back to the kind of electric blue melancholy they had only dared to chance once before – on Bon’s totemic Ride On.

But if Night Prowler musically exceeded its elegiac descendent, Bon’s lyrics were something else: the tale of the beast that waits for you to ‘turn out the light’ before it ‘makes a mess of you’. If the music hadn’t been so convincing, the song might have fallen into Alice Cooper-type schlock-horror. But Lange’s production ruled out any thoughts of theatrical contrivance: it just sounded mean and dirty.

Lyrically, other tracks, like the bouncing Girl’s Got Rhythm and Beating Around The Bush – the latter remodelled from the discarded Dirty Deeds track Backseat Confidential, with a new, flintier riff barely one remove from that of Fleetwood Mac’s Oh Well – came straight out of the same bottom drawer as the rest of Bon’s dirty-minded fantasies. But musically, this was a whole other universe. The craft that went into Walk All Over You was like a George Young production in reverse, Lange introducing a more sophisticated set of dynamics that turned an otherwise average blues romp into something touched by greatness. Similarly, Shot Down In Flames was pop-rock taken to its zenith.

“Mutt took them through so many changes,” says Ian Jeffery, who was there at many of the sessions. “I remember one day Bon coming in with his lyrics to If You Want Blood. He starts doing it and he’s struggling, you know? There’s more fucking breath than voice coming out. Mutt says to him, ‘Listen, you’ve got to co-ordinate your breathing’. Bon was like, ‘You’re so fucking good, cunt, you do it!’. Mutt sat in his seat and did it without standing up! That was when they all went, ‘What the fucking hell we dealing with here?’.”

Lange also taught Angus some useful lessons, instructing him to play his solos while sitting next to the producer. “Mutt said: ‘Sit here and I’ll tell you what I want you to play’,” recalls Jeffery. “Angus was like, ‘You fucking will, will ya?’. But he sat next to Mutt and Mutt didn’t force it on him, just kind of pointed at the fretboard and, ‘Here, this…’ and ‘Hold that…’ and ‘Now go into that…’ It was the solo from Highway To Hell. It was fantastic! And that really stood them all to attention on Mutt too. He wasn’t asking them to do anything he couldn’t do himself, or getting on their case saying it’s been wrong in the past; nothing like that. He really massaged them into what became that album.”

Always first in and last out, Lange would sleep on the studio couch, working after everyone else had gone home, going through the day’s performances, weighing, judging, discarding. Like a master finding his muse, AC/DC had provided the producer with his greatest canvas. Unlike the punk-conscious acts he’d toiled with previously in London, AC/DC not only could play, but they didn’t give a fuck what anyone else might have to say about it after the fact. This time around there were no sneaky tapes being sent back to George, either. While the elder Young still fumed over his removal from the studio, no one could argue with the results Lange was getting. Not that the band had forgotten about their brother’s sacking. But it would be their manager, Michael Browning, who bore the brunt of that deep hurt.

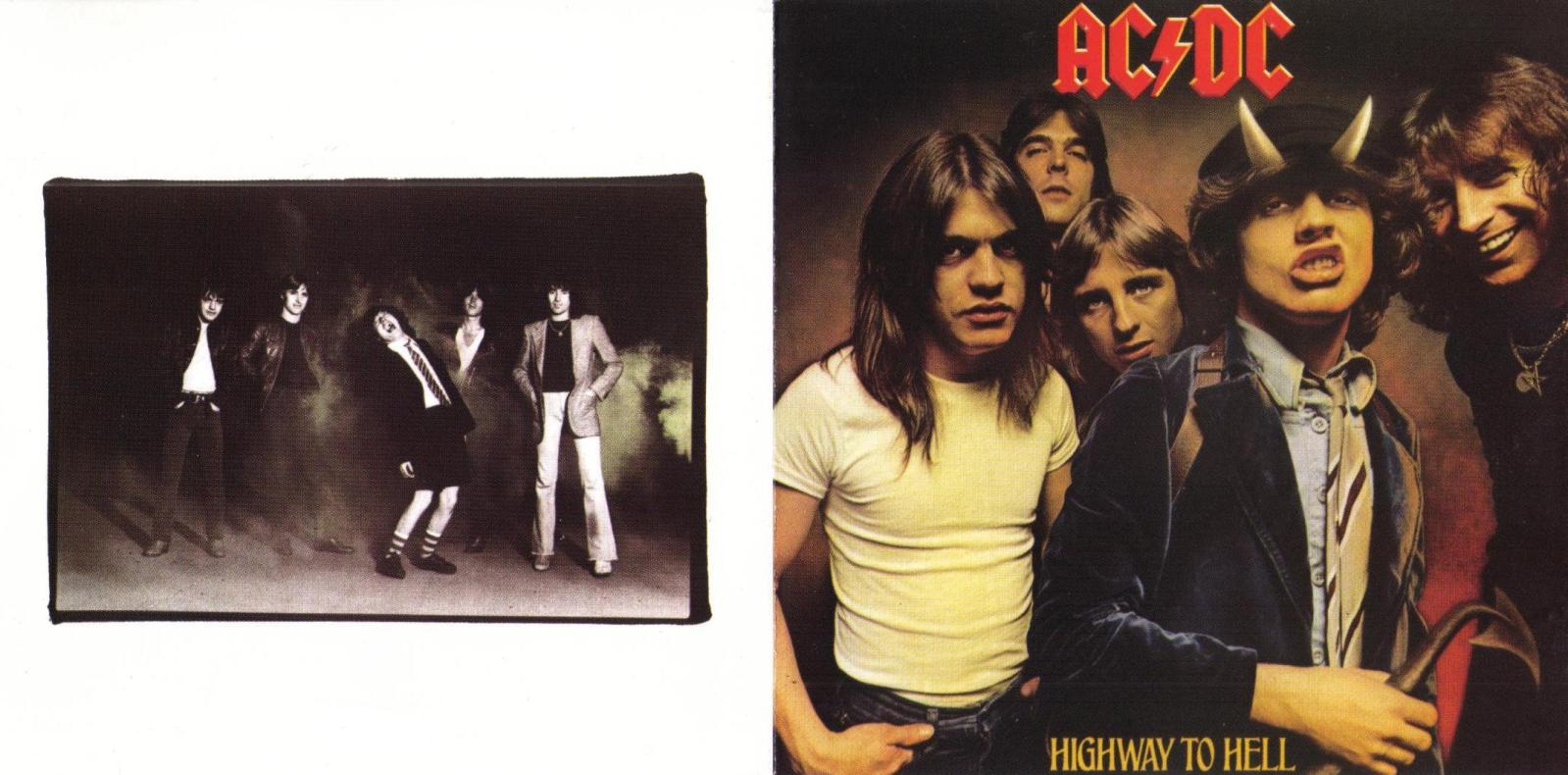

The first time Browning heard Highway To Hell was at home in New York, where Malcolm played it for him. “It was obvious from the word go it was something special,” says Browning. “I thought the title track was the absolute breakthrough they needed for America, and then we sort of got into the process of working out the cover and that sort of stuff.”

More to the point, the powers that be at Atlantic actually agreed. “We all liked what Mutt Lange did,” says Barry Bergman, the band’s American publisher at the time. “Highway To Hell made both AC/DC and Mutt Lange in America.”

Indeed, it launched Lange as the producer de jour in the US. But if everything was looking rosy again on the surface, as ever with AC/DC, there were rumblings that few saw coming. Atlantic decided they didn’t like the album title and tried to get them to change it. “They freaked,” remembered Malcolm. “But we told them to stick it.”

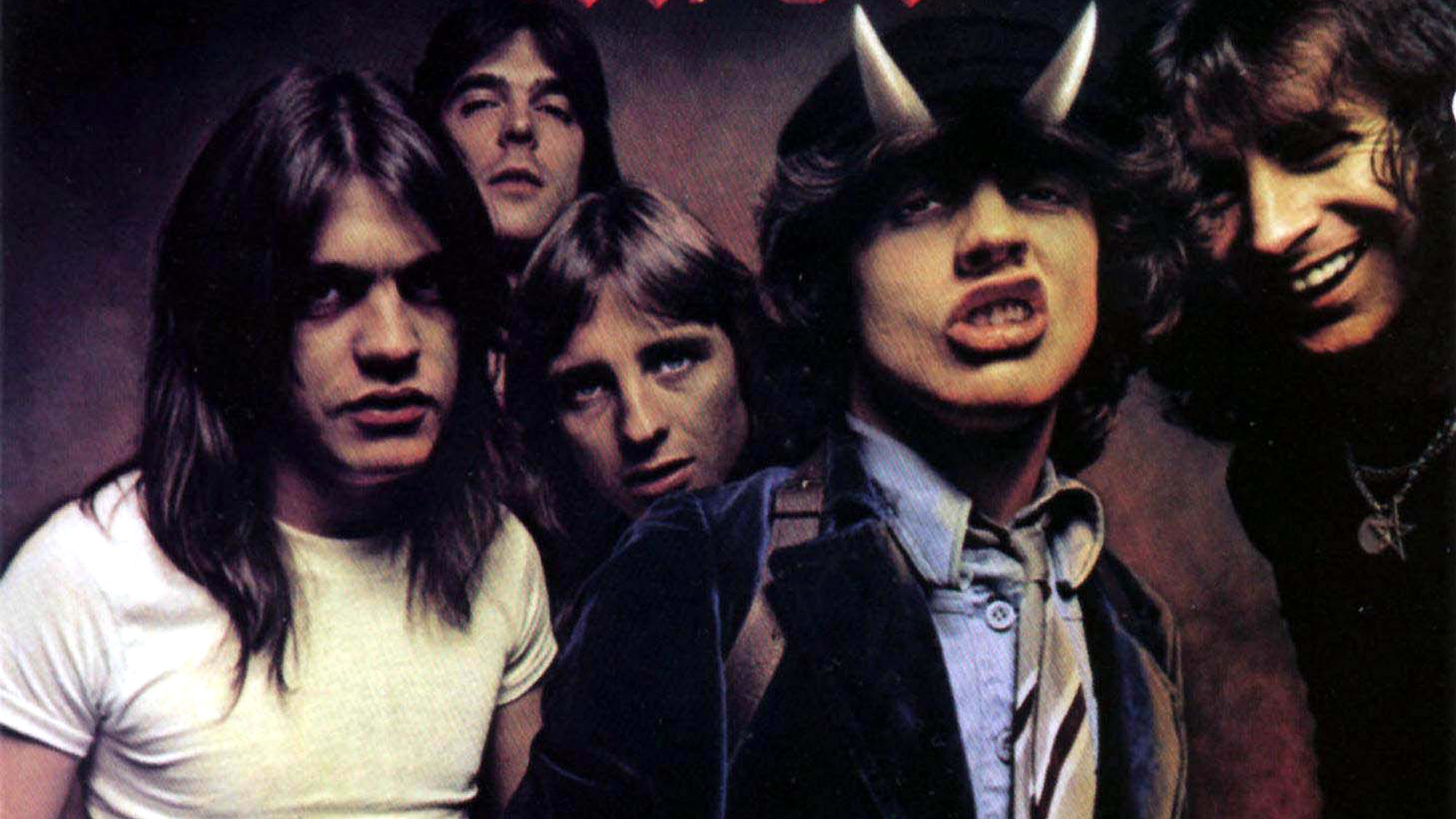

There were also concerns over the front cover. One option had Angus on his own on the cover, with toy devil horns on his head and a curly little forked devil’s tail, but that had been rejected by the band, says Ian Jeffery, “because it was fucking shite”. The band wanted to go with a nondescript line-up shot from the same session. The record company suggested they use the solo shot of Angus, but AC/DC wouldn’t be budged. “Who the fuck do they think they are?” spat Malcolm of the label.

Unfortunately for Browning, the ripples didn’t end there. Following what he calls “an unbelievable argument between me and the group” after a show on the subsequent tour, he was fired. “I don’t think they ever forgave me for helping move George out of the picture,” he says now.

Nevertheless, the result was AC/DC’s first major international hit album; their first to crack the US Top 20, eventually selling more than seven million copies; their first to get into the UK Top 10 and go gold; and their first hit record back home in Australia for three years. Highway To Hell – both song and album – are now rightly considered all-time rock classics. It marked the start of a whole new era for AC/DC – and the beginning of the end for Bon Scott.

This was published in Classic Rock issue 191.

Mick Wall is the UK's best-known rock writer, author and TV and radio programme maker, and is the author of numerous critically-acclaimed books, including definitive, bestselling titles on Led Zeppelin (When Giants Walked the Earth), Metallica (Enter Night), AC/DC (Hell Ain't a Bad Place To Be), Black Sabbath (Symptom of the Universe), Lou Reed, The Doors (Love Becomes a Funeral Pyre), Guns N' Roses and Lemmy. He lives in England.