50 years of Judas Priest: the ultimate interview

Judas Priest are still very much around after 50-plus years, through ups and downs. We spoke to all the current members about life in one of the greatest metal bands of them all

There’s a cactus in the yard of Rob Halford’s home in Phoenix, Arizona that looks like it’s throwing the horns. It makes frequent appearances in the Judas Priest frontman’s Instagram feed, itself one of the most joyous and life-affirming things on the internet.

The 69-year-old does social media like few other rock stars of his vintage. Recent pictures of him posing in spiked, diamante-encrusted high-heeled boots appear alongside classic photos of a young Halford wearing a period-piece late-70s tracksuit and leaning against an old 12-speed racer outside his old house in Walsall. Inevitably there are shots of cats too. Lots of shots of cats.

Anyway, back to the cactus. It’s been in Halford’s yard since he moved to Phoenix from the West Midlands in 1986. Back then it was a common-or-garden desert shrub, proud and erect if not yet fully metalised. But over the decades it has gradually sprouted a pair of distinct digits a foot or two apart pointing directly heavenwards.

“They’re my Percy Thrower heavy metal fingers,” Halfords says, undoubtedly the only heavy metal singer who would dream of referencing a long-time deceased British TV gardener. “That cactus has grown incrementally into that shape. I guess that’s the effect I have – I turn everything into metal.”

Halford and his bandmates have been turning everything they touch to metal for 50 years now. Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath laid the foundations for the genre, but it was Priest who reshaped it in their own image – everyone from Metallica to Motley Crue bears their musical DNA, while anyone who has stood in front of a camera or walked on stage encased in leather, studs or a combination of both has got it straight from the Judas Priest playbook.

The band are currently marking their Golden Jubilee with a series of US dates, and last month saw a headlining appearance at the UK’s Bloodstock Festival. There’s also the small matter of recording a follow-up to 2018’s stellar Firepower album although Halford is under strict orders not to give anything away. But there’s plenty to talk about even without that, chiefly Priest’s none-more-epic 50-year journey.

“We were just so full of adventure,” says Halford, speaking over Zoom from the house he shares with his partner of 30 years, Thomas Pence. “But you never really grow up in a band, you’re just having a laugh. And you’ve got to be able to laugh, because you’re about to go through some life-changing experiences, for good and bad.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Rob Halford

Before Judas Priest, there was Judas Priest. That Priest were kicking around Birmingham in the late 60s, an entirely different entity to the one that followed. When bassist Ian Hill and guitarist KK Downing brought in singer Al Atkins from the original Judas Priest to join their new band, uninspiringly christened Freight, he brought the name with him. But it was only when Hill began dating Halford’s sister and heard him singing that the pieces fell into place.

“Ian says it was Ella Fitzgerald, Ken [KK] said it was Doris Day,” says Halford. “I can’t remember what it was, but it definitely fucking wasn’t Doris Day.”

Your dad worked at the local steelworks. Was there ever any chance of you following him and going to work there too?

I think there was a very good chance. That’s what lads did in the West Midlands – they went to work where their dad worked. I went to my dad’s place a few times as a younger lad. I saw enough of it to think: “This is I where I’d end up until I retire and they give me a gold watch.” That’s a motivation for a lot of musicians – you don’t want to end up where your dad’s working.

Were you a show-off as a kid?

Yeah, I think we all are, us singers. Anything for attention. I remember once on a Sunday afternoon when I was five or six, I went into my grandmother’s handbag and found her make-up and did myself up as a drag queen. I remember coming in and my grandma going: “Oh, it’s a nancy-boy!” I was grinning, with the rouge and the eyeliner, looking like Dusty Springfield on crack. It was hysterical.

You spent a few years acting in your late teens. What was the attraction?

I was just enthralled by everything to do with escapism, breaking away from the reality of life. I grew up in a household where the telly or the radio was always on, there was always something going on in the background, whether it was films or music. I was just naturally inquisitive for that kind of life. I still am. I wanted to be a part of it.

A post shared by Metal God (@robhalfordlegacy)

A photo posted by on

You also managed a friend’s adult bookstore for a couple of weeks. What are the upsides of working in a porn shop?

[Laughing] You can have a surreptitious wank when there’s no customers around. No, you learn to read people – you can tell what they’re going to go for as soon as they walk through the door: “He’s going to go for the bondage”; “He’s going to go for the big tits.”

Funnily enough, history repeated itself decades later. I was doing this movie, Spun [in which Halford plays the manager of an adult shop]. I’m in this porn shop in Santa Monica with [co-star] Mickey Rourke, and he goes: “It hasn’t changed much in here.” I go: “What do you mean?” He says: “I used to work here while I was trying to get work in Hollywood.” I said: “Have I got a story to tell you.”

You joined Judas Priest in 1973. Did you ever see them play with Al Atkins?

I have a very murky memory of seeing the band play at the Birmingham College Of Food And Art. I think they’d been together for about three weeks at that point and already the word was buzzing. There was practically nothing on stage, but you’re instinctively drawn towards something that has great potential. That’s how it was with Priest and me.

Priest’s debut album, Rocka Rolla, came out in 1974. Did you think: “This is it, we’re heading for the big time?”

Oh yeah. I was living at my parents’ house, and I remember the postman knocking at the door and handing me my one copy of the record. I was, like: “Ker-ching!” If only I knew.

Did you find those early years tough?

We were on nuppence a week from the label [Gull Records, who released Priest’s first two albums]. We’d been doing shows up and down the country non-stop, we were getting a strong following, and we were saying to them: “Why can’t you support us? We only want a fiver a week. That’s all we need to be able to quit our day jobs.”

Was there ever a time when you thought of quitting music?

No, never. Even when me and Ian were stuck in the back of a broken-down van in Germany, and it was minus-30 Celsius outside. The guys had gone off to get help, except they hadn’t, cos they were at some local club getting pissed and having a knees up while me and Ian nearly died of hypothermia. They got back at nine or ten in the morning, and we’re covered in frost. Ian looked like a cross between Chewbacca and a yeti. He was pulling icicles out of his beard. But the hard times are the memories you cherish the most.

Between 1975’s Sad Wings Of Destiny and 1980’s British Steel, Priest released a string of albums that match Black Sabbath’s first six records as one of the greatest straight runs in history. With each one, their sound came into sharper focus – intricate yet bludgeoning, tuneful yet dramatic.

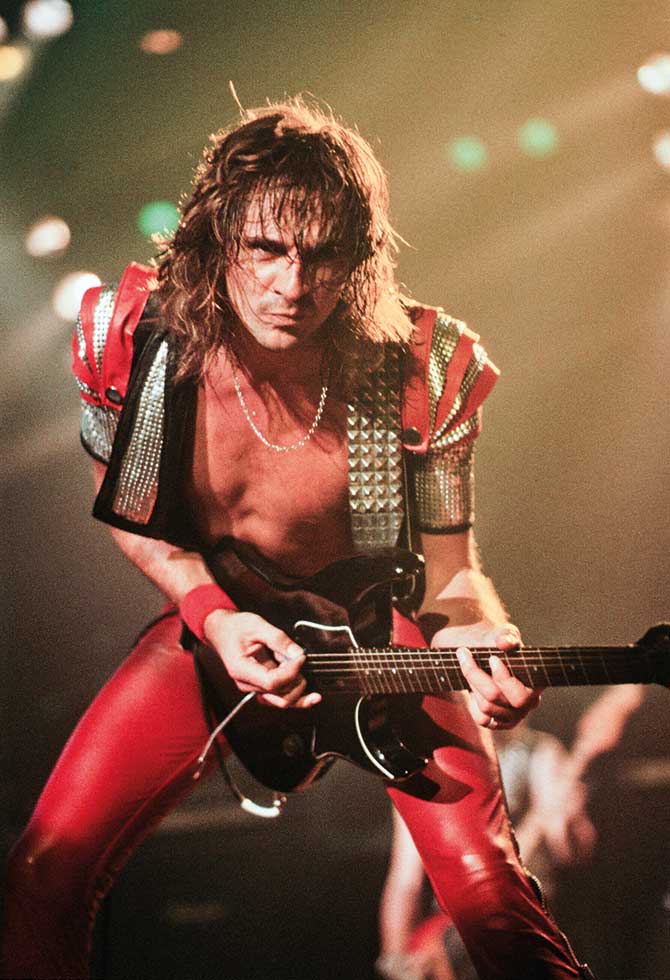

The image underwent a more radical overhaul. By the time of 1978’s Stained Class, the mix-and-match kaftans, trilby hats and women’s blouses sported by the nascent Priest were gone, replaced by a heavy-on-the-leather image that was equal parts motorbike gang and S&M dungeon chic.

It was KK Downing who hit on the idea of dressing up in leather. You’ve always said that you never made the connection with the gay scene or the S&M scene. Is that true?

I swear. [Points at himself] Look at this naive little Walsall-lad face. I never drew a parallel. I was clueless about the filth and the depravity and the debauchery. I’d love to say I was leafing through Bad Boys In Bondage and suddenly went: “Oh, I like the way he’s looking”, but I never did. It was purely this great experimentation, just seeing what worked. Something happens when I put my gear on. It’s just a wonderful feeling. You change.

Raw Deal, from Sin After Sin, was the first in a long line of songs you wrote about sex: Evil Fantasies, Eat Me Alive, Jawbreaker, Pain And Pleasure… People always overlook what a randy band Priest could be.

I think you’re focusing a little bit too much on a few of the hundreds of songs we’ve written, but I do take your point. Raw Deal was a remarkable song for me as a lyricist. People sometimes reference it as the ‘coming out’ song, because it mentions [New York gay mecca] Fire Island. But it was never intended to be that. It was just a great bunch of words about this place I’d never been to – and still haven’t. But yes, some of those songs have sexual innuendo. Because we’re all made for sex. You can’t escape those three letters.

The flip-side is tracks like Last Rose Of Summer from Sin After Sin, or Before The Dawn from Killing Machine, which are love songs.

Before The Dawn was a reference to a guy I was seeing over here in America. It was all about young love, that first serious relationship. But there are very few songs that I’ve written with an attachment to a real person. Out In The Cold [from 1986’s Turbo] was one. That was about Brad [Halford’s former boyfriend, who committed suicide in 1986]. And Turbo Lover was probably relative to the bathhouses I used to frequent back in the day.

A lot of bands at that stage in their career would have moved to London to give themselves a leg-up, but you stayed in the West Midlands.

We thought the London scene didn’t understand the band or the music. They looked down on us. Some of the early reviews we had… classic ‘don’t quit your day jobs, guys’ stuff. But that was kind of an incentive.

Which bands were you hanging out with back then? Who were your rock-star buddies?

[Laughs] I didn’t have any. Maybe that was because I was so off my tits that I can’t remember having any conversations. I was down the pub every night. But remember, this is the West Midlands, there really wasn’t that much going on.

British Steel, in 1980, was the band’s big leap forward. What was it like being in Judas Priest around that time?

That was a special time. It took exactly thirty days to make that whole album, from the day we went into the studio to the day it was mastered. And of course that’s when Priest became a household name in the UK. But there was never any intent on our part to write songs that would take us to that place. We were just having a blast. Every day was a good day.

A couple of years later, Screaming For Vengeance kicked everything to the next level for Priest, especially in the US. Did you enjoy that degree of fame?

We worked really, really hard in America, and because of that hard slog we got to that point where we were successful. But once you’re in it, you can’t let go of it. You can’t take your foot off the accelerator. We were doing five, six, seven shows a week, travelling hundreds of miles overnight, giving it loads of welly.

Some people have said that Priest never cared about the British fans, that America meant more. That’s not true. We did great things for British heavy metal in America. But we couldn’t walk away for even six months. We had to keep coming back here to keep the momentum going.

Do you know the term ‘Fuck-you money’? It means you’ve made enough money to be able to say ‘fuck you’ when people ask you to do something. When did Priest start earning fuck-you money?

[Laughs] Hand on heart, I don’t think we’ve ever been able to say we’ve had fuck-you money. One of the most beautiful moments I had was when I got my first big royalty cheque and I bought my little house in Walsall. Which I’ve still got. I was able to buy that house, cash, for thirty grand. That’s as probably as close as I got to fuck-you money. Until the tax bills started coming in and I had to give half my money away.

Speaking of your house in Walsall, there’s a photo on Instagram of you standing outside it, next to a greenhouse. It looks like you’re growing pot in there.

That was a mate of mine, Nick, who I lived with before I bought that house. He was the horticulturalist. I was in there one day and I could smell something: “This smells familiar.” I think he’d been popping in there at night and cultivating his herbs.

You had a torrid time with drugs and alcohol in the 1980s…

For me it was a massive combination of booze and drugs and toxic relationships and having to hide my sexual identity. It was just a ball of fucking shit. I got into the cocaine thing very simply. It’s like when you’ve been drinking beer all your life and somebody goes: “Have a shot of Johnnie Walker.” That’s what it was like for me, going from booze to having a spliff to cocaine.

Did you ever get into heroin?

I didn’t. That was a no-go area for me. Just the thought of putting a needle in my arm was taboo.

From the outside, that didn’t seem to impact on the band. Did you ever bring your problems into the office?

Well, you hide that stuff, whether it’s booze problems or drug problems or marital problems. But that’s when bands become dysfunctional. That’s why it’s important to be so honest and open and forthright with each other, no matter how difficult it is. It’s not all on your own back, you can share the load of what you’re going through. It makes you stronger.

You got sober at the start of 1986. But a few years later the band were hit with a lawsuit from the families of two boys who had allegedly killed themselves after listening to Stained Class.

That was extraordinary. They tried to push the blame for that on us, and that is a terrible thing to do.

Were you confident you’d win?

No. Because we knew about the American court system, we knew how things could go sideways. It was unusual territory, these so-called subliminal messages.

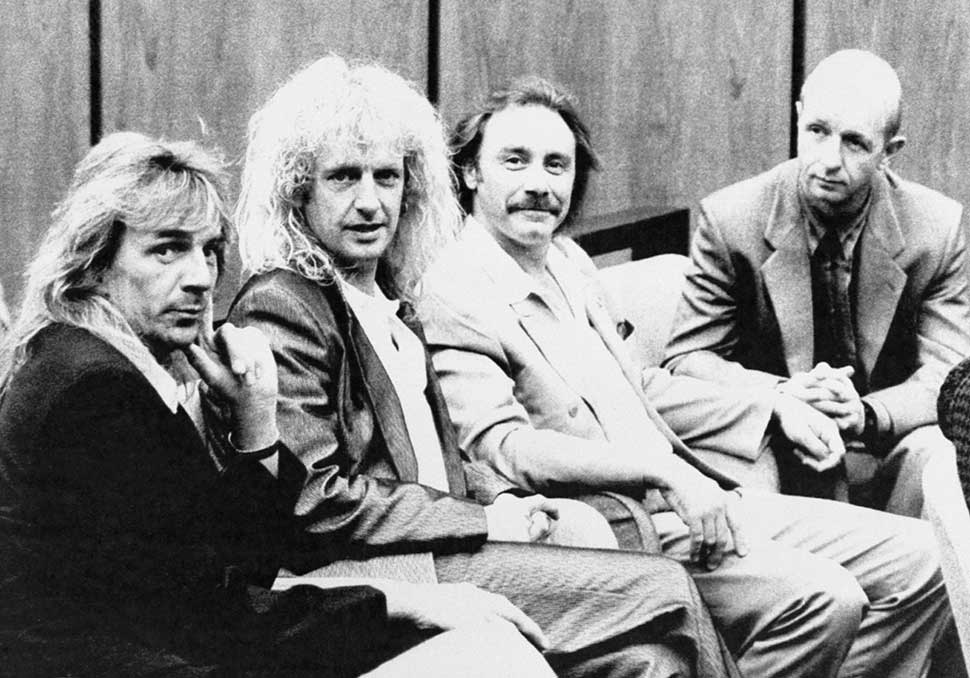

There’s a famous photo of the four of you wearing suits and sitting in court. What do you see when you look at that photo?

I see a bunch of guys who were very confused, very angry, very determined. We knew that we were absolutely going to have to do the best job possible to get the truth out, so we made all the necessary adjustments and accommodations – wear suits, be respectful to the court and the judge. The prosecution created this fictitious rock’n’roll lifestyle that we were allegedly living, but we came in as four intelligent British gentlemen who knew how to deal with what was presented to us.

You were eventually cleared by the judge. Did you all go out and celebrate?

No. I’d gone off to Puerto Vallarta in Mexico to hide, because the press were after us. Somebody called me up and said: “The judge has exonerated you, it’s the end of the case, it’s done and dusted.” But no, we didn’t celebrate. We were just relieved. And what got lost in all of it was the loss of these two beautiful, tragic lads. That’s the sadness of it all.

Judas Priest entered the 1990s as a band renewed. Their first album of the new decade, Painkiller, made up the ground lost by 1986’s successful yet divisive Turbo and 1988’s underpowered Ram It Down.

But it wasn’t all good news. The Painkiller tour ended abruptly and with a bump when Halford rode a motorcycle on stage and straight into a steel bar, knocking him off the bike and knocking him out. The accident marked the end of a chapter of Priest’s career.

Soon afterwards, Halford embarked on a solo career that eventually saw him quitting Priest.

What does it feel like to rid a motorbike into a steel bar?

I can relive that whole episode, from leaving the dressing room to trying to get to the stage before the intro tape ended. I’m yelling at someone to do the tape again, the steps are coming down, I give it some throttle… and the next thing I know, someone’s kicking me, and it’s Glenn. I still haven’t got the cartilage in my nose fixed. Thomas has got to have some work done on his nose [laughs], from picking it. I said: “When you go in, we’ll both have it done together.”

You were out of the band for eleven years. Did you think: “I don’t need those guys, I can do it on my own”, or did you miss them?

I missed them from the very start. I never once had that “I’ll show you” mentality. I remember talking to the guys around the time of the Turbo album, saying: “I’ve got this idea of doing some stuff on the side.” They were like: “‘Yeah, we might do that ourselves. Just make sure it doesn’t clash with the band.”

That was the green light we gave each other back then. So I felt that once I’d made the Fight album, War Of Words, to me that was it: ‘I’m ready to come back, let’s go.’ But there were some people working for me who were not making the appropriate things happen in terms of communication, so it wasn’t to be.

Did you listen to the two albums Priest made with your replacement, Tim ‘Ripper’ Owens?

No. I still haven’t. This might sound selfish, but because it’s not me singing, I’m not attracted to it. I sound like a twat, but I’m really just not interested. And that’s no disrespect to Ripper, cos he’s a friend of mine.

Where did you first meet him?

When the band went through Ohio he came to the show. Was it awkward? Not in the least. We gave each other a hug. He’s a massive Priest fan, and when the opportunity came for me to go back, he was like: “Thumbs up, it’s great. I’m happy for the band, I’m happy for Rob.” I respect his chops, he’s a great singer.

You officially rejoined Priest in 2003. What was the first meeting between all of you like?

I’d seen Ian around, and I’d made sure I’d spoken to Ken and Glenn. But the first time we all had a meeting together was at the Holiday Inn in Swiss Cottage, just to talk about the business plan of the reunion and the record and the rest of it. It was very informal, but for some reason I put a suit on. Bill [Curbishley, manager] was like: “Why are you wearing a suit?” I just went: “I have no idea."

Were there any kind of apologies made by either side?

Well, I’d written a heartfelt letter to the band before I rejoined. I went and sat in a coffee shop in San Diego and poured my heart out. I basically laid out the feelings I was having, the fact that I missed Priest more than anything I could say, if there was any chance for us to get back together then I couldn’t wait for that day. It was a six- or seven-page letter, and I know that all the lads saw it, and that was enough. But I don’t think I ever went: “Oh, I’ve been a naughty boy, I’m sorry.” I’d love to read it again. I think it’s somewhere in the office.

The reunion found Halford and Priest picking up where they left off 11 years earlier. The four albums they have released since then have range from the solid (2005’s Angel Of Retribution, 2014’s Redeemer Of Souls) to the ambitious (2008’s bold, if over-reaching, Nostradamus) to the genuinely spectacular (Firepower, the best Priest album since their 80s heyday).

There have been bumps in the road. Founding guitarist KK Downing departed in 2011 and was replaced by Richie Faulkner (the relationship between Priest and Downing seems to be cool at best).

Fellow guitarist Glenn Tipton announced in 2018 that he was stepping back from playing with the band after being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, although he is still involved with the band. As for Rob Halford, he endures, occupying a unique position as Metal God, late-life LGBTQ+ icon and the ultimate ambassador for not just Judas Priest but also heavy metal as a whole.

Does it feel to you that Priest have had the recognition and respect they deserve?

Yes, it does. And it’s beautiful. Your music has permeated all around the world, it’s filtered through to all of these places. It’s a lovely feeling to have that come back at you. It only reinforces you even more to continue flying that flag of British heavy metal.

I’ve always wondered: Priest were named after a Bob Dylan song, The Ballad Of Frankie Lee And Judas Priest. Have you ever met him?

I met him for about three minutes when [Halford’s solo band] Fight were doing a show at the Sony Studios. One of the label people said: “Bob Dylan’s in the next room. Do you want to meet him?” I’m like: [enthusiastically] “Yeah, who doesn’t want to meet Dylan?” So this guy takes me round to this room. And there’s Bob, he’s got five or six chicks hanging out with him.

And this record guy goes: “Bob, here’s somebody I’d like to introduce you to, it’s Rob Halford, he’s from the British heavy metal band Judas Priest.” And Bob goes: [spot-on Dylan impression] “Heeeeey, what’s goin’ on? What’s happenin’?” And I go: “Hey Bob, it’s really nice to meet you.” And he goes: “Where ya from?” I say: “I’m from Birmingham.” And he goes: “Birmingham?” [pause]. “How’s Ozzy doin?” Then I was whisked off.

Does it bother you that Priest aren’t in the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame?

It doesn’t bother me, not at all.

Where are things at with the new Priest album?

We had one really big writing session, the songs were great, they were really instinctive… I’ve got to stop talking or management will kneecap me.

It seems like you get a lot of joy out of being in Judas Priest.

It completes me musically. Everything I want in music comes from this band. I don’t need to go anywhere else. That’s what I discovered when I was away from the band.

Do you ever look back over Priest’s career and think: “How the hell did that happen?”

Oh yes. For us in metal, this was a whole new experience. We were literally making it up as we went along. [Laughs] We were clueless

Ian Hill

The bassist has been with Priest from the beginning, through thick and thin. And while he’s enjoyed spending time at home with his family recently, he’s missing being out on the road.

You were there at the beginning. Can you remember the very first Judas Priest gig?

I remember it well. It was Essington Working Men’s Club, just outside of Walsall There were only about twelve people there.

What did you make of Rob Halford the first time you met him?

The first thing I heard was his voice. I was going out with his sister, Sue, and he was still living with their mum and dad. He’s always been an easy-going guy, a pragmatist, a bit like myself.

What was it like being in Judas Priest in those early days?

It was brilliant. We’d load all our gear in the back of the van, then put the mattresses on top of the gear and that’s where we slept. We played pubs and Student Unions and places like The Cavern. You’d be at some Working Men’s Club in the north and they’d be looking over their pints at you, deadpan. Then the committee head would come bumbling on stage halfway through and ask you to read the raffle [laughs].

What did you think when Rob said he was going to ride a motorbike on stage?

We thought it was a bit mad, but it was one of those great ideas. We got in touch with Harley-Davidson and asked if they’d be interested in providing a motorcycle for us. They wouldn’t give us one, but they’d sell us one for a dollar. So that’s what we paid for it - a dollar.

Is it true that you’ve still got the original Harley?

I think it’s the basic frame. It’s got something like twenty-seven miles on it. In the early days they’d let you start the thing up and drive it on. But then the fire marshals got a bit nervous. They said: “You can have it on stage but you can’t have any fuel in it.” So we have to roll it on.

Priest supported Led Zeppelin in San Francisco at the end of your first US tour in 1977. What was that like?

We were on at something like ten in the morning, and when we came out there was so much fog that we couldn’t see the audience. As we started to play, the fog began to burn off, and we started to see one row, then another. Then it lifted completely and we were like: “Jesus, look at all these people!”

Priest were playing pretty big gigs of their own within a few years. Did that level of fame mess with your head?

It did to start with. You think: “Christ, all these people have come to see us.” It’s a bit awe-inspiring. But if you do it long enough the jitters go. You’re going out there to do a job.

Priest caused a riot at Madison Square Garden in 1984. What was it like being in the middle of it?

It was surreal. Someone tore the foam out of a seat and threw it on stage, then somebody thought: “That’s a good idea.” Suddenly there were whole seats coming up on stage. It was hilarious. We got banned from playing there.

When were you un-banned?

We haven’t been. But Ken [KK Downing] and Glenn [Tipton] went a few years later to see something or other. One of the stewards nudged them and said: “Thanks for the new seats, lads.”

How did you feel when Priest’s Eat Me Alive ended up on the PMRC’s Filthy Fifteen?

It was nonsense. It was a bunch of ignorant politicians’ wives. They didn’t have the slightest idea about poplar culture – it was all evil and must be eliminated. Same with the court case we went through. Subliminal messaging? That was just a trumped-up charge.

Rob had his problems with drugs and booze in the eighties. Did you steer clear of those things?

Not entirely, no. But it was never dangerous with any of us. It never got to the dangerous point. Even then, I was stone-cold sober when I went on stage. I had too much respect for the fans.

How were the 1990s for you?

Turbulent. Rob wanted to go and do a solo album, which ended up evolving into a solo career. If things had been handled differently it could have been very different. But we were determined to get through it and prove people wrong.

Had you bumped into Rob before he rejoined?

He didn’t know it, but I went to see him play at the NEC in Birmingham. They were good, too. And then Ken and myself were at Rob’s mum and dad’s golden wedding anniversary. That was the big ice-melter. We saw each other and hugged. And the next thing you know he was back with us. Even Ripper knew it was a good idea.

Do you care that Judas Priest aren’t in the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame?

To be honest, no. These things come along and they’re great, it means you’re being recognised by your peers. But when you don’t get them you move on, it doesn’t make any difference.

How many more Priest albums do you have in you?

There is one in the pipeline at the moment. These days you have to take things one step at a time. We’ll carry on as long as we can give quality performances. If the quality starts to fall off, there’s not much point going on.

You must have thought about the day when Judas Priest will no longer be part of your life.

I’ve enjoyed the last year, being with my family, pottering in the garage, mowing the lawns. But I am terribly missing not being out on the road. So that’ll be a sweet and sour moment when it does come.

Glenn Tipton

It hasn’t all been a joyride, but the guitarist wouldn’t want to have done anything other than “travelling the world, doing what I love most – playing guitar”.

You joined Judas Priest in 1974. Had you seen them play before you joined?

Yes. I had been to see them on a couple of occasions at small clubs around the Midlands.

Can you still remember playing your first gig with Priest?

I’ll never forget it. It was at Birmingham Town Hall. We had a self-made PA system which blew up halfway through the show. We had no sound expect for the back line, but we carried on regardless. The audience thought it was all part of the show and we went down a storm.

What were those early days like, when you were all crammed into the back of a van, living on virtually no money?

It was worse the grim! When we recorded Sad Wings Of Destiny [’76] we slept in a Transit van outside the studio in London. We were issued meal tickets by the label – I think we were allowed three a day. But it did build our inner strength as a band and bought us close together. Especially in the Transit van.

Did you have any Spinal Tap moments during those early days?

It was all Spinal Tap! One time we were rehearsing at Pinewood Studios and we had bed and breakfast in a nunnery. The nuns were in shock – they thought Judas Priest was some kind of religious sect. But when we left them they were quite sad. They asked if we’d play at their summer fête. We thought it better to pass.

Was there a point where you thought: “Bloody hell, I’m famous!”?

No. But I never felt I’m famous.

Can you remember what you spent your first big royalty cheque on?

I gave some money to my parents and bought them a house to thank them and for understanding me not getting a ‘real job’. My father never did quite understand, though, until we were on TV around the time of The Old Grey Whistle Test [’75, playing Rocka Rolla]. There was a point where Priest were one of the biggest metal bands on the planet. Did that mess with your head? Not really. I don’t think we realised how influential Priest was going to become.

Priest played the US Festival in California in 1983. What was that like?

It was an incredible day. We flew in by helicopter over 320,000 people – there was a sea of people. It was so hot that the guitars kept going out of tune during the show, and our guitar techs had to keep retuning them. But it was metal history.

Priest ended up on the PMRC’s ‘Filthy Fifteen’ list with Eat Me Alive. Could you see their point?

Absolutely not. Anyone who was offended by the lyrics didn’t get what the song was about.

Rob Halford has written some fairly near-the-knuckle songs about sex. Did you ever asked him to tone it down?

Rob’s a great lyricist and doesn’t need anyone to tell him what to write.

Rob had his struggles with drugs and alcohol in the eighties. Were you worried about him?

Of course. But he went to rehab and overcame his addictions through his own strength and got on with his life and career. Total respect.

What about you – were you ever in danger of going down that slope?

I don’t have an addictive nature, plus the amount of drugs and alcohol I did was small, really. I believe you can only cure addiction by beating it yourself.

Have you ever come close to quitting Priest?

Only in the early days when we’d be on tour for six months with no money. I questioned whether it was worth leaving my family and my children for. But thankfully I stayed and it was all worthwhile in the end.

Had Priest ever come close to splitting up?

Not splitting up. Some of us have done projects outside of Priest, but never with the intention of splitting up the band.

In the past few years you’ve had to step back from playing with Priest. How difficult was that for you emotionally?

It was one of the hardest things I’ve had to do in my career and my life. When I stepped on to the stage after making that decision, the fans’ reaction was immense. So warm and emotional. It was very rewarding. But you have to get on with life – accept and suddenly see things in a different perspective. Never surrender!

Do you care that Priest aren’t in the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame?

Not really. I’d be proud to be inducted – we have been nominated a couple of times – but the people who have the final vote don’t really know about metal. There are so many artists that should be in there but aren’t – just like us.

Apart from presumably having a few quid in the bank, what’s been the best thing about being in Judas Priest?

Creativity. I’ve been able to achieve so much in my life and reach goals that I wouldn’t have done if I hadn’t been in Judas Priest. What could be better than travelling the world, doing what I love most – playing guitar?

The band’s most recent album, 2018’s Firepower, was brilliant. How do you follow it up?

We can only try.

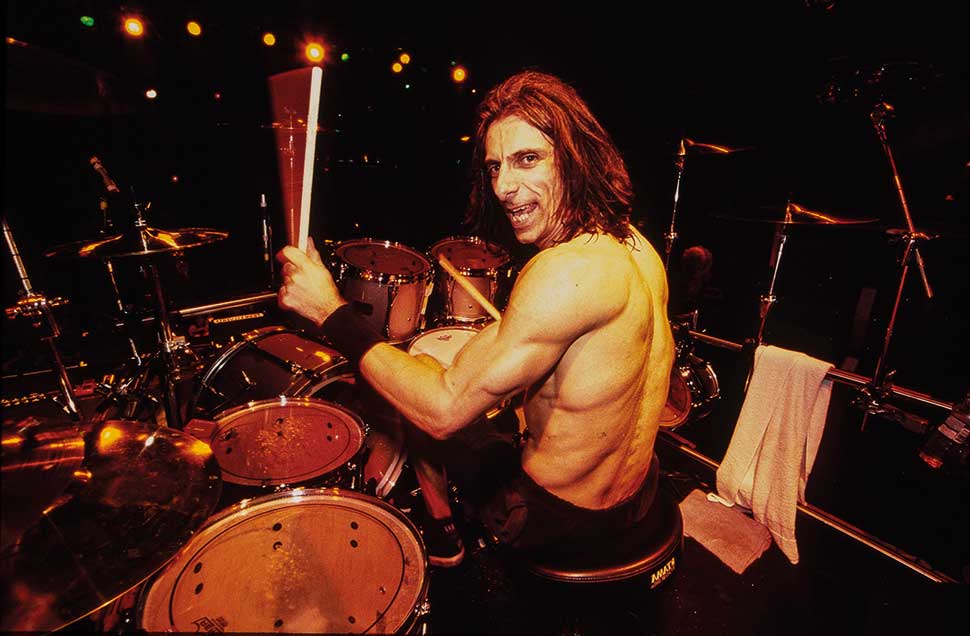

Scott Travis

The former Racer X drummer was already a Priest fan before he joined them in 1989, and he was also in Rob Halford’s side project Fight.

Were you a big Judas Priest fan growing up?

Absolutely. A friend of mine had Unleashed In The East on cassette, and one time we were riding around in my car and he ended up leaving it. So I borrowed it and I loved it. Then, like most fans, I went backwards and started. The first time I saw them was on [1981’s] the Point Of Entry tour. Iron Maiden with Paul Di’Anno were opening up for them.

Did you see them and think: “One day that’ll be me up there on the drums?”

Ha! Here’s the deal. I grew up on the Les Binks era – Hell Bent For Leather (aka Killing Machine in Europe) is my favourite album to this day. When they got in Dave Holland, they still wrote great songs, but when I saw them in concert I was like: “Man, that drummer doesn’t seem to be pulling his weight.” I was a big fan of the music and the image, but it felt like it was missing something there.

How did you end up becoming Priest’s drummer nearly ten years later?

I was in the band Racer X. Our singer, Jeff Martin, had been in a band called Surgical Steel, in Phoenix, and he’d known Rob from just hanging out on the local rock scene. So when Rob mentioned to Jeff one day that they were looking for a drummer, he said: “You gotta check out my guy Scott.” He threw my name into the hat, and then the band flew me over to Spain in the latter part of 1989 to audition.

Your introduction to Priest fans was the drumming that opens 1990’s Painkiller album, on the title track.

That’s a hell of a way to start. Oh yeah. When you’re a drummer you want a signature opening drum riff – Zeppelin’s Rock And Roll, Van Halen’s Hot For Teacher. I guess that one was mine.

You were in Rob’s side-project Fight as well as Priest. Wasn’t that awkward?

No, it was really cool. Rob asked me if I wanted to be part of Fight. I asked Glenn and Ian and KK if they were okay with it and they said absolutely. They thought it was good to keep at least two members of Priest in the same solo project.

Did you ever try to broker peace between the two sides?

No, I just stayed out of it and didn’t get involved.

How do you look back on the two Priest albums you made with Tim ‘Ripper’ Owens?

They’re different. They obviously wanted the sound to be different, they didn’t want to drop in a singer who sounded just like Rob, even though Ripper has a lot of elements that can sound like Rob. But they were what they were.

Who’s arse-kicker-in-chief in Priest these days?

Well Glenn’s always been the one, musically speaking. He’s the one going: “Here’s the ideas, here’s what we want to do.” But you can’t do anything in rock’n’roll without a singer, and Rob’s a great songwriter and a great lyricist.

What’s Rob Halford really like?

[Laughs] Well, he’s a big fan of his own flatulence. No, one thing I’ll never get is when I flew to Spain to audition. I had a long, long flight back. I’m getting ready to leave, and he calls me: “I can’t say for sure you’ve got that gig, but I want you to feel confident, wink wink.” He knew I had long flight, so that was a classy thing to do.

Priest got through a lot of drummers before you came along. What’s your secret?

Dude, I don’t know. I was a Priest fan before and I’m still a Priest fan now. I’d listen to them now

Richie Faulkner

Priest’s ‘new boy’, who replaced KK Downing, has been with the band since 2011 and has so far played on 2014’s Redeemer Of Souls and their latest album, 2018’s Firepower.

How did you get the job as Priest guitarist?

In true musician form, it was two p.m. and I was in bed – I’d taken someone to the airport early that morning and I was catching up on sleep – when the phone rang. I picked it up and said: “Who the bloody hell is that?” It was Priest’s management. They said they’d been trying to get hold of me for a while via email. I looked in my deleted folder there were a load of emails from them that I’d deleted.

Did you already know there was a vacancy?

It was the first I’d heard about it. At the time it wasn’t a vacancy as such, it was just a temporary thing – could I do some of the upcoming tour. Ken [KK Downing] had completely quit, but they didn’t want that out there.

Who tipped them the nod about you?

I‘d been playing with [former Almighty guitarist] Pete Friesen, who I’d played with in a covers band called Metalworks, where we’d done Priest songs. He knew some of the crew, and they asked him, but he politely declined and put my name forward.

What was your Priest album growing up?

Painkiller. I knew Breaking The Law, Electric Eye… but when Painkiller came in with the drum intro, I was like: “What the hell is that?”

What was your audition like?

Glenn took me to the studio where he had a rig set up. He told me to get set up then he left to make a coffee. Unbeknown to me, he was standing at the bottom of the stairs, listening to me just noodling. He came up and said he’d have been embarrassed if someone had asked him to just play something. I said: “My whole life has been building to this point. If I can’t think of anything to play I might as well just go home.”

At first did you feel like a bit like the work experience kid?

Not at all. Right from the start it was very apparent that they wanted a member of the band, they didn’t want a hired gun. They would always ask what I thought. I think they appreciated that they had someone in from the outside who might have a different insight into how the band is perceived.

Your first gig with Priest was an appearance on American Idol. What was that like?

It was surreal. Tens of millions of people are watching it, but you can’t think about that. If you did you’d just buckle. You just think: “We’re flying the flag for metal, putting it into thirty million households.”

You work closely with Glenn. What’s he like?

He’s one of the loveliest people in the world. People say: “Is he a father figure?” He’s more like an older brother. You can mess up together with him and he’ll laugh about it. He’s an incredible teacher. And he wears very cool white loafers.

What’s an argument like in Judas Priest?

I’ve honestly never seen one. I’ve seen differences of opinion, but it was all constructive. That’s one thing Rob said to me: “You’ve got to get that stuff out or you’re going to be unhappy, it’s going to breed resentment, then we’ll put out a record that you’re going to be huffing over.”

Rob and Glenn both said you saved the band.

They saved me. We’re a five-spoke wheel.

Which is your favourite Priest album now?

Defenders Of The Faith. The Sentinel, Freewheel Burning… There’s something about that album that hits me in a different way.

Judas Priest’s Reflections: 50 Heavy Metal Years Of Music is out on October 15 via Sony.

Dave Everley has been writing about and occasionally humming along to music since the early 90s. During that time, he has been Deputy Editor on Kerrang! and Classic Rock, Associate Editor on Q magazine and staff writer/tea boy on Raw, not necessarily in that order. He has written for Metal Hammer, Louder, Prog, the Observer, Select, Mojo, the Evening Standard and the totally legendary Ultrakill. He is still waiting for Billy Gibbons to send him a bottle of hot sauce he was promised several years ago.