How Pink Floyd became the ‘go to’ rock band for space scientists

Pink Floyd may have hated the term ‘space rock’, but in 1988 their music was the chosen soundtrack for the crew of the Soviet spacecraft Soyuz TM-7

In March 1973, Roger Waters and Nick Mason were interviewed in the British rock magazine Zigzag. Pink Floyd had just released Dark Side Of The Moon. Asked what they thought of their music being described as ‘space rock’, you can almost hear Waters groaning as he replied, “Christ! I hardly ever read science fiction… People listen to Dark Side Of The Moon and call it ‘space rock’ just because it’s got moon in the title…”

Despite Waters rejecting the tag, Pink Floyd did have past form. In the Zigzag interview, Waters grudgingly conceded that, yes, they’d written three songs which fitted the bill: Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun, Astronomy Domine and Let There Be More Light.

In fact, Waters later said he’d borrowed the lyrics to Set The Controls… from a book of ancient Chinese poetry rather than a science fiction novel. That said, 1967’s Astronomy Domine began with the sound of Pink Floyd co-manager Peter Jenner reciting a list of planets and zodiac signs through a megaphone in his best schoolmaster’s voice.

Meanwhile, Let There Be More Light, a song written by Waters and released as a US single in 1968, was based on a tall tale told by one of the Floyd’s roadies whose father claimed to have seen an alien spaceship land at Mildenhall in the Cambridge fens.

Certainly, by the 1970s, Floyd were writing songs about more earthly matters and human emotions. But, musically, many of their greatest dreamy soundscapes (Echoes and Shine On You Crazy Diamond to name just two) still evoked the sensation of floating in space, comfortably numb and nicely disconnected from Planet Earth.

Furthermore, on July 20 1969, Pink Floyd performed in a BBC TV studio, providing a freeform instrumental jam while the station broadcast footage of the first moon landing. The BBC’s programme, Omnibus: So What If It’s Just Green Cheese, also featured actors Dudley Moore, Ian McKellan, Michael Hordern and Judi Dench alongside Pink Floyd.

“The programming was a little looser in those days,” David Gilmour told The Guardian in 2009, “and if a producer of a late-night programme felt like it, they would do something a bit off the wall… It was a live broadcast, and there was a panel of scientists on one side of the studio, with us on the other.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“They were broadcasting the moon landing and they thought that to provide a bit of a break they would show us jamming,” he added. “It was only about five minutes long. The song was called Moonhead - it’s a nice, atmospheric, spacey, 12-bar blues.” Moonhead was never released but, inevitably, can be found online.

In Gilmour’s memory, however, it did mark the point at which Floyd’s music, and especially, Waters’ lyrics started to change: “I think that was sort of the end of our exploration into outer space.”

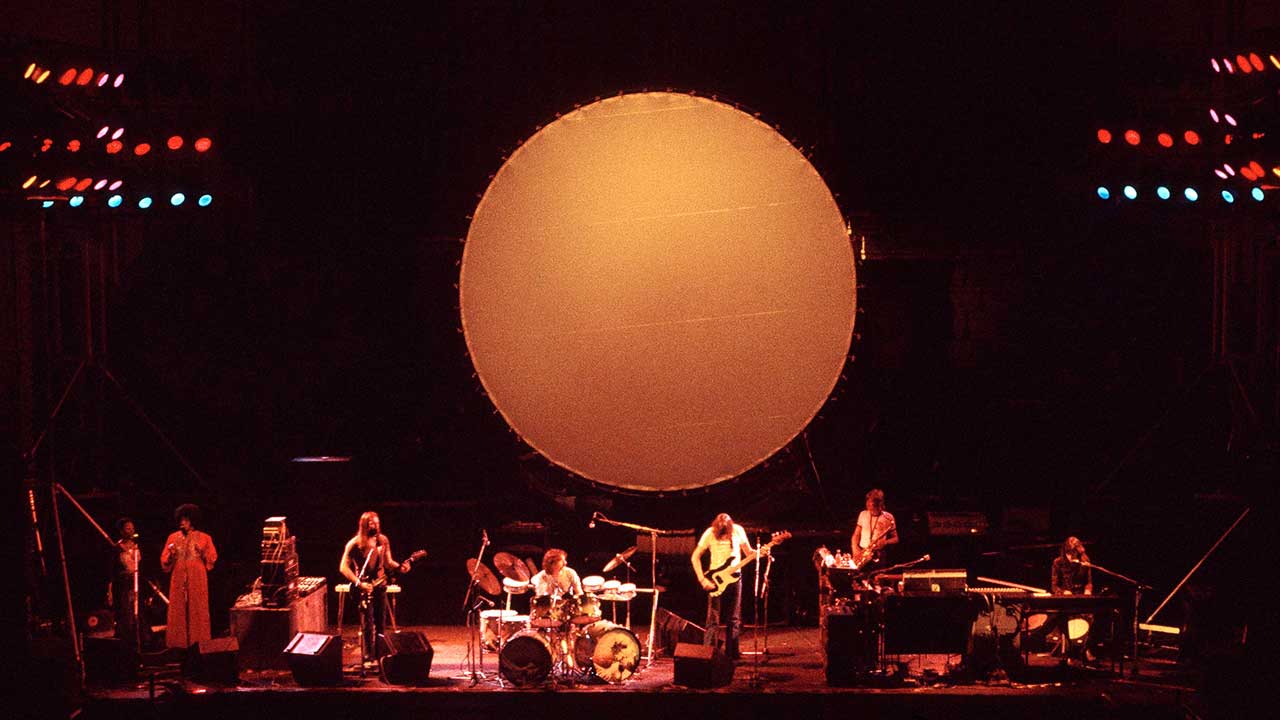

However, Pink Floyd’s relationship with outer space wasn’t done yet. Nineteen years after the first moon landing, Floyd became the first rock group to have their music played in space. On November 22, 1988, Floyd released a live album, Delicate Sound Of Thunder, recorded at New York’s Nassau Coliseum on their recent world tour.

Six days later, on November 28, David Gilmour and Nick Mason attended the launch of the Soviet spacecraft Soyuz TM-7 at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. The crew, cosmonauts Sergei Krikalyov and Alexander Vokov, took with them a cassette copy of Delicate Sound Of Thunder (minus the box for weight reasons).

The cosmonauts had requested the album to listen to as they completed their mission of docking with the orbiting Mir space station. Delicate Sound Of Thunder was also the only Pink Floyd album to receive an official release in the Soviet Union. “To say that we are thrilled at the thought of being the first rock band to be played in space is something of an understatement,” said Gilmour.

As grand publicity stunts go, there could be few grander than having your album played on a spaceship. At the time, Pink Floyd were all about making their presence known anywhere in the world – and now the universe. The tour on which Delicate Sound Of Thunder was recorded marked the grand return of Pink Floyd, minus Roger Waters. Waters and his former bandmates had been engaged in a bitter war of words over the use of the Floyd name, with Waters threatening legal action and publicly denouncing the Gilmour, Mason, Wright ensemble as a fake and a forgery.

Unfortunately for Waters, his new solo album, Radio K.A.O.S., had sold modestly, and his recent tour found him struggling to fill theatres, while his former band sold out football stadiums. Pink Floyd having their new album played in space while Waters struggled to get his played on earth seemed like the final twist of the knife.

Having sampled the delights of Shine on You Crazy Diamond, Wish You Were Here and Us And Them, the Soviet cosmonauts left their copy of Delicate Sound Of Thunder on the Mir space station, and came home. The station remained active until 2001, when a gradual de-orbiting process began. It finally re-entered the earth’s atmosphere in March that year, burning up and fragmenting into the South Pacific Ocean near Fiji, presumably with the Floyd cassette still on board.

Clearly, though, Pink Floyd had set a precedent as the ‘go to’ rock band for space scientists. On March 10, 2004, NASA used the Floyd song Eclipse from Dark Side Of The Moon to ‘wake’ its robotic probe, Opportunity, which had landed on Mars two months earlier. Perhaps, then, Pink Floyd’s journey into space will never truly be over.

Mark Blake is a music journalist and author. His work has appeared in The Times and The Daily Telegraph, and the magazines Q, Mojo, Classic Rock, Music Week and Prog. He is the author of Pigs Might Fly: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd, Is This the Real Life: The Untold Story of Queen, Magnifico! The A–Z Of Queen, Peter Grant, The Story Of Rock's Greatest Manager and Pretend You're in a War: The Who & The Sixties.