You can trust Louder

It’s a little ironic, and rather at odds with the original’s small, scruffy, black-and-white xeroxed design, but Ramones’ 1976 debut album – all 29 minutes and four seconds of it – has been somewhat enhanced. It’s now grandly packaged in a 12x12-inch hardcover book and includes the album on vinyl and over three CDs, all produced, mixed and mastered by original producer Craig Leon.

There are “meticulously recreated” mono and “sonically superior remastered” stereo versions on one disc, plus a disc of single mixes, outtakes and previously unheard demos, and a third featuring two full sets recorded live at The Roxy in West Hollywood on August 12, 1976, the second of which makes its official debut here.

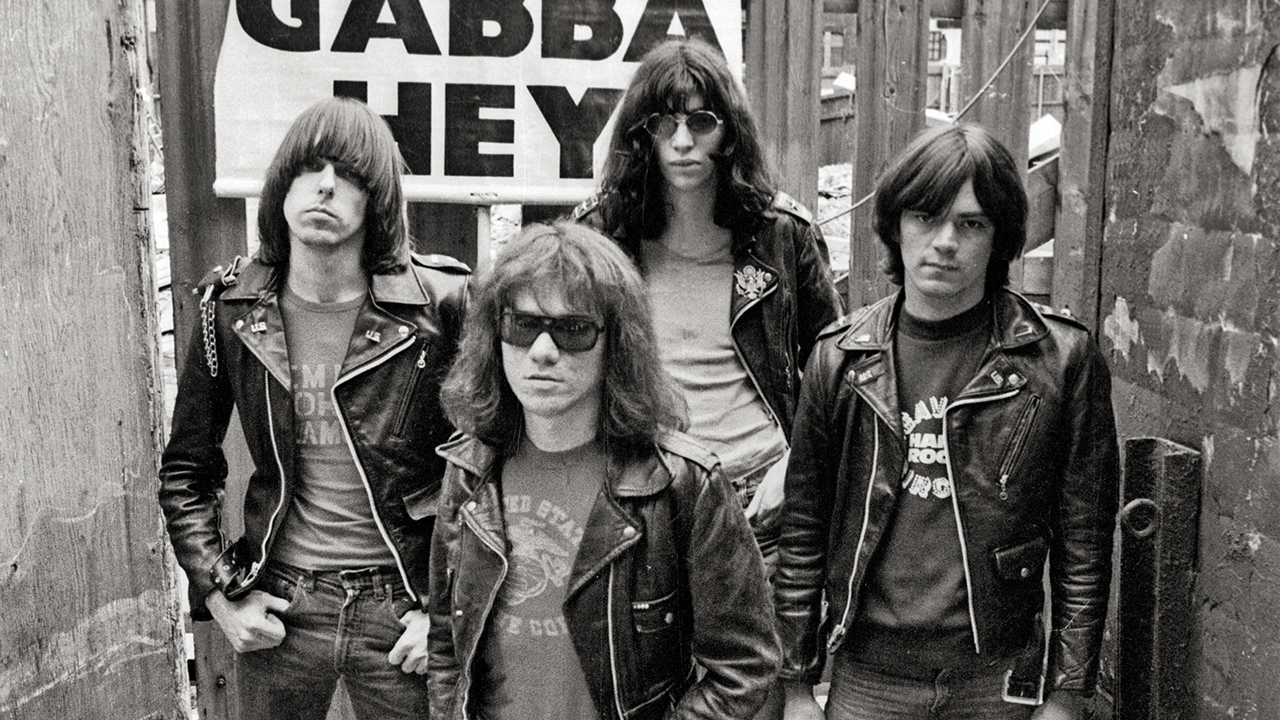

You also get production notes exploring the making of the album, an essay on the band’s formative days, and pictures by Roberta Bayley, whose indelible street-hood image of ‘da brudders’ provided the album’s front cover. There are 19,760 individually numbered copies of this deluxe set, which is just over three times as many as it sold on its initial release, even though millions will swear they bought it on day one.

Too many albums are cited as influential, but in this case, notwithstanding its meagre performance at the box office, it could be reasonably argued that virtually every one of those 6,000 sales were courtesy of key or burgeoning musicians, journalists and creative types, catalysing the birth of an entire movement. Put simply, the Sex Pistols played the Marquee on February 12, 1976, Ramones’ debut album was released on April 23, and then punk happened. Overnight, songs got shorter and music got faster and more furious.

But it’s a misconception, even a myth, that Ramones were doyens of dumb who just turned up, plugged in and somehow magicked their live set into a 14-track long-player. “We were trying to emulate their live sound, but we were also trying to enhance it,” Leon told this writer earlier this year, stressing that studio trickery – overdubs, double-tracked vocals – as well as everything from pipe organs to Tubular Bells were deployed on Ramones: it took sophisticated techniques to sound this primitive and raw.

Listening to the album today, you have to wade through 40 years of hype before you can make your mind up. Even if you’d never heard it before, virtually every note, of Side One at least, is recognisable: the language of cartoon mayhem – Blitzkrieg Bop, Beat On The Brat, Now I Wanna Sniff Some Glue, Chain Saw – and Joey Ramone’s pretty-vacant vocals, the ‘Eh-oh, let’s go!’ and ‘Wun-tew-free-faw!’ chants, Dee Dee’s pummelling bass, Johnny’s sped-up dentist-drill guitars and Tommy’s double-time glam beat. As with Taxi Driver, that other significant 1976 arty-fact, you could pause it anywhere and ‘freeze-frame’ an iconic moment.

It’s quite an achievement that after four decades of extreme metal and hip hop, the references to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (on Chain Saw), male prostitution (53rd & 3rd) and Nazis (on LP closer Today Your Love, Tomorrow The World) still have the power to disconcert, if not outright disturb.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

But for all its air of new-era violence, what surprises is how in hock to history it is, and how tame many of its sentiments are. Ramones is equal parts homage and sabotage, as much of a launchpad for future generations as it is a love letter to the 50s and 60s. The controversial exhortations (Beat On The Brat, Now I Wanna Sniff Some Glue) are balanced out by embarrassingly timid demurrals (the reason they Don’t Wanna Go Down To The Basement is because they’re scared!), that employ arcane beatnik argot (‘Hey, daddio’). I Don’t Wanna Walk Around With You (‘I don’t wanna walk around with you/So why you wanna walk around with me?’) sounds less cruel and nihilistic than childishly churlish, while on I Wanna Be Your Boyfriend, Ramones play the part of the submissive, insecure male, in a state of feeble longing (‘Do you love me babe?/What do you say?’), which hardly suited the punk credo of ‘no feeling’.

On the cover of Let’s Dance, they nail their colours to the mast and it’s the past: what appears to be cheek and desecration is actually not-so-secret love and guilty pleasure. Even on Chain Saw, for all the allusions to slasher cinema and punk boredom (‘Sitting here with nothin’ to do’), the real reason Joey sounds so forlorn is because his girlfriend has gone to watch the titular Texan massacre and he won’t see her for hours (‘She’ll never get out of there’).

There’s no cessation of relations between then and now; in fact, the relationship is symbiotic. Throughout, Ramones rely on old values for base matter to transform from gold to grot. Without Phil Spector’s romantic tropes or the Beach Boys’ harmonies, they wouldn’t have had anything to punk/puke up.

Ramones is often described as a masterpiece of compact brevity, shorn of excess, but at two minutes and 33 seconds, Beat On The Brat, the longest track, could have done with losing 45 seconds. There’s another paradox about Ramones: for such a monument to iconoclasm, it feels sacrilegious to be even faintly criticising it. Still, it also occurs that by Judy Is A Punk, Ramones have said everything, espoused their philosophy with such consummate precision that they could have ended it there, with what would have been a blistering three-track EP. Or it could have all been neatly contained within the first side, leaving the flip empty for the blank generation. On the other hand, Ramones might have worked best as a 20-track onslaught.

The truth lies somewhere in between, which is why hindsight looks as favourably upon Ramones in its ultimate 14-track iteration as did first-sight critics such as Nick Kent, who reviewed it on the week of release for the NME, where he deemed it “an object lesson in how to successfully record neanderthal hard-rock”. Besides, it’s only after multiple plays that you realise Loudmouth and the rest on what used to be Side Two help paint the full (albeit monochrome) picture of these denizens of New York’s Lower East Side.

Without the harmonically complex (these things being relative) Loudmouth, we would never have got to hear Ramones using six chords instead of their usual three. Without 53rd & 3rd we would never have learned about Dee Dee’s rent-boy past (even if we might not, in this more enlightened age, be ecstatic to discover that he, or at least his fictional counterpart, kills his ‘client’ with a razor to prove he isn’t gay). And without Today Your Love, Tomorrow The World (‘I’m a Nazi schatze/Y’know I fight for fatherland’ ), Ramones – 50 per cent Jewish, remember – would never have had the chance to mock right-wing creeps everywhere. Ramones didn’t run out of ideas over the distance of their debut album because they weren’t about ideas plural, but The Idea, singular – that the world is absurd, dangerous but full of opportunities for mischief and fun, which they rammed home with ruthless relentlessness.

Ramones have been credited with pioneering many things – punk, speed metal, hardcore and more – but they were their own greatest invention. Even if, in the wake of all the hard and heavy music that has come since, their noise isn’t quite as full- frontally lobotomising as it once was, the way they were able to conjure an entire universe with its own customs, look and stance, from scratch, remains as startling as ever. The coup lies in the sheer consistency of its conceptual coherence. Of course, it’s more musically limited than those other epochal debuts by The Stooges, MC5, the Modern Lovers, New York Dolls and Suicide, but it has to be. That’s its central point.

In that spirit, you’ll either consider the extras in this Ramones-fest to be digressions or essential additions. There are two types of Ramones fan: those that favour the debut album and maybe the two that followed (1977’s Leave Home and Rocket To Russia), relishing the purity of that triptych; and those obsessed completists who buy into the Ramones aesthetic so comprehensively that nothing less than everything is enough.

The latter will be amply served here. Of particular merit is the mono version of the album, which heightens the brutal simplicity of Ramones’ bubblegum beat-pop. It might not bludgeon you into delighted submission, not any more, but it will confirm the brilliance of this sustained act of calculation.

Paul Lester is the editor of Record Collector. He began freelancing for Melody Maker in the late 80s, and was later made Features Editor. He was a member of the team that launched Uncut Magazine, where he became Deputy Editor. In 2006 he went freelance again and has written for The Guardian, The Times, the Sunday Times, the Telegraph, Classic Rock, Q and the Jewish Chronicle. He has also written books on Oasis, Blur, Pulp, Bjork, The Verve, Gang Of Four, Wire, Lady Gaga, Robbie Williams, the Spice Girls, and Pink.