"I was thinking I was going to go down in history as the man who killed Howlin' Wolf": What happened when English rock royalty worked with a real blues icon

Now revered as a linchpin moment in the history of the blues, Howlin’ Wolf’s 1970 London Sessions were recorded with Eric Clapton and various Stones and Beatles. This is the story, told by those who were there

It all started with a chance encounter several months earlier at a show in San Francisco. Backstage at the gig, blues guitarist Mike Bloomfield of the Electric Flag introduced Eric Clapton to Chess Records producer Norman Dayron.

In the course of a rambling conversation about their blues heroes, Dayron floated the idea that he might be able to put together an album on which Clapton would play with the legendary Howlin’ Wolf. Clapton’s eyes lit up but there was one catch.

Nobody had yet suggested the idea to Howlin’ Wolf.

May 1, 1970 : Howlin’ Wolf, Hubert Sumlin, Jeff Carp, Norman Dayron and others fly to London.

Norman Dayron: When I had first told Wolf what I was thinking of, he thought it was a horrible idea. He didn’t know who these guys were, but we’d worked together, and he trusted me, so he came round to it.

In all there were about 10 people in our party, professional bluesmen from Chicago, in case any of the English guys Clapton had organised didn’t show up. As it turned out, I only needed to use Hubert and our 18-year-old harmonica wizard Jeff Carp. Myself and all of my musicians stayed at The Cumberland Hotel, and we had a small fleet of taxis organised to drive them down to Olympic Studios every day.

Hubert Sumlin: The company [Chess Records] in the States just wanted Wolf with Eric Clapton and the rest of the guys. They was going to leave me back. Eric made a statement, telegraphed these people. If I wasn’t going to be on there, he wasn’t going to be on there. So they said to me, “Hey man, pack your bags – you got to go!”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Norman Dayron: It was always my intention that Hubert would come with us. I was, by this time, an independent producer, so I controlled the budget, I booked the tickets. It’s conceivable that Leonard Chess may have had a private conversation with Hubert and may have said something like that to him, but I wanted him there.

Hubert had been concerned about what his role was going to be. I explained, before we left Chicago, that I wanted him to play rhythm guitar, and he was perfectly happy about that.

Eric Clapton: The guy that organised the session wanted me to play lead instead of Hubert Sumlin. Hubert ended up supplementing, playing rhythm, which I thought was all wrong, because he knew all the parts that were necessary and I didn’t.

Ringo Starr: Two memories are that Howlin’ Wolf was incredible! And his guitarist – he had this guitarist with him who was just so fuckin’ incredible. Eric was on the sessions and he just let the guy take it, y’know. It was really a moment to see, Mr Guitar himself bowing to this guy who really played the way [Eric] played.

May 2, 1970 : Olympic Studios, London, recording I Ain’t Superstitious, Goin’ Down Slow and I Want To Have A Word With You.

Glyn Johns (engineer): I had received a call from the fellow who, so-called, produced it. He was an American. His name was Norman Dayron and he proved to be a complete inadequate. He said that he wanted to re-record Howlin’ Wolf, using a bunch of English rock’n’roll musicians. He’d booked Olympic Studios and asked if I’d engineer it, and I said I would.

Norman Dayron: When I got to Olympic, one of the first things I realised was that their recording techniques were more designed for classical music than blues. They used lots of condenser microphones which did not give the kind of focused, sharp sound that we were getting at Chess. Regrettably, I was not subtle in making suggestions about how to change the sound.

Glyn Johns was a famous, talented engineer with his own style, and to have a brash young kid saying, “That is not the sound I want,” put us at odds. I don’t think he knew I’d been working at Chess since the mid-60s, starting as a janitor, then becoming an engineer and finally a producer. I had been trained by Willie Dixon and I knew exactly how to get the Chess sound.

Glyn Johns: I threw him out of the control room on the first day, I remember. I banned him because he’d come in and play what we were going to do next. He’d get the [original] record out and put it on the turntable at the wrong speed and not realise that it was at the wrong speed. Can you believe it? So I said, “You! Out! I can’t deal with you anymore. Get out of here.”

Norman Dayron: It’s true that we didn’t get along at first, but he never threw me out of the control room. For a start, I was not the kind of producer who sat behind the desk in the control room and said, “Take one.” I preferred to be out there with the musicians and you can see that in the photographs of the sessions.

But Glyn and I did have a number of which I thought was all wrong, because he knew all the parts that back-and-forth discussions and finally I accepted that he had gotten enough of an idea of the kind of sound I was looking for that I could trust him to follow those precepts and it would be OK. I also knew I could work further on the sound when I got back to Chicago.

Hubert Sumlin: Wolf was on a dialysis machine right in the studio, with doctors tending him night and day.

Norman Dayron: I can’t imagine where Hubert might have got that from. Wolf’s problems at that time were with his heart, not his kidneys.

His problem was arrhythmia, which was easily controlled by prescription drugs. I had gone with him in Chicago to see his doctor, who knew him well. She gave the green light for him coming to London because otherwise he’d probably have taken his band down to play in some juke joint in Greenwood, Mississippi, which would have been much worse for his health.

So part of my responsibility on that trip was to make sure he took his pills. A bigger problem on the first day was that Charlie Watts, who Eric had organised for the session, couldn’t be there. I think Bill Wyman did show up, but he was not keen to play without Charlie. We put out an urgent call for musicians and the first pair to turn up were Ringo Starr and Klaus Voormann.

Klaus Voormann (bassist): Bill Wyman was definitely there that first day. I remember because I was surprised by how talkative he was. I’d only seen him on stage where he stood there with a straight face.

Norman Dayron: Bill was very keen to support the project but Ringo and Klaus knew each other and had played together often, so they were the obvious choice for that first day.

Klaus Voormann: Wolf sat on a chair, but there was no control coming from him. In fact, there was no control from anywhere. I remember the whole band sitting there after having played a few takes.

Howlin’ Wolf was staring at the floor, sitting there like a statue, not moving an inch. He gave us no comment, so we didn’t know, “Was it good? Was it bad? What shall we do?”

Eventually, Ringo very cautiously spoke into the drum mike in the direction of the control room: “Shall we try it a little...”

At that point, Howlin’ stopped Ringo by lifting his right hand, with his left pointing at the control room, saying, “He’s the producer.”

Norman Dayron: I was kind of pushy, so all through the sessions, when people would look to Wolf and ask for guidance, he would say, “Ask Norman. He knows what he wants. He’s the boss.” They had to ask me.

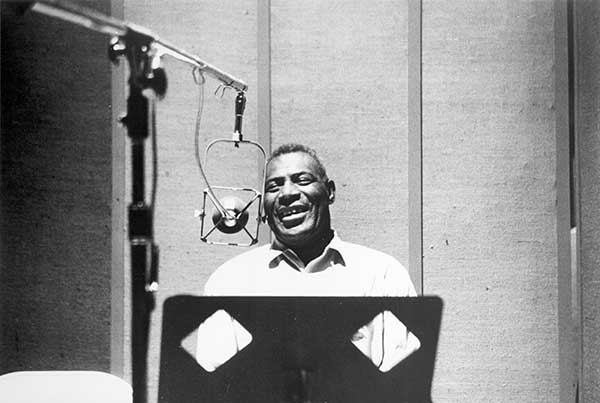

Klaus Voormann: Once we got started, Wolf took the microphone off the mike stand, walked up to us, bending down real close, looking us in the face with his dark eyes, singing his arse off. What power! What magic. What a great guy!

Ringo Starr: He was great. He was the Wolf Man. He was Howlin’ fuckin’ Wolf! We had all the baffles around the drums and I had the cans on and my eyes closed, playing to him and then suddenly it just seemed a bit... the air was hot coming across my face and I looked up and he was right over the baffles singing, right into me and the drums, so he didn’t care about separation and I love that. So they’re the memories. He was just, y’know, a gentle giant on those sessions.

Norman Dayron: Ringo and Klaus caught on right away to what we were trying to do. One of the best songs on there, I Ain’t Superstitious, features Ringo and Klaus. They did a good job.

Eric Clapton: For the first couple of days, I was scared of The Wolf, because he wasn’t saying anything to anyone. He just sat there in a corner and let this young white kid kinda run the show and tell everyone what to do. It was a bit strange.

Glyn Johns: Eric Clapton in those days wasn’t quite the hero that he became He kept saying, “What the hell am I doing this for? Hubert Sumlin’s in the control room. Why don’t you get him to come and do it?” Eric didn’t want to do it. He was very modest and was quite embarrassed too.

Norman Dayron: At the end of the day, Clapton asked if he should bother coming back. I said, “Don’t worry, it’ll be better tomorrow.”

May 3, 1970: Olympic Studios. Bill Wyman and Charlie Watts take over as rhythm section, with Rolling Stones pianist Ian Stewart on piano.

Ian Stewart (keyboardist, Rolling Stones): The producer phoned me and asked me to help him set it all up. People do this. They come and pick your brains, they want you to help, and then say, “Well, if you do it, you can play piano.” You know, rhubarb, rhubarb, so I played piano on all of that and then he went away and took the tapes to Chicago and got hold of Stevie Winwood and said, “Would you overdub piano because there’s no piano on it?”

Norman Dayron: On the second day in Olympic, Wolf got surly. I don’t think it was about the musicians. I think it was just his mood. He was working with people that he had no real connection with. I think he was uncomfortable, and the way he expressed that was by being rather blunt and aggressive.

He was like a fish out of water. Wolf was prepared to work, but he was going to be surly about it. We got through some good takes but there was still no real connection, there wasn’t that magic in the room where people were having fun playing together and, without that, you’ve got nothing.

I later found out that he was drinking heavily and not taking his medicines. However, I believe this was the day when we made a breakthrough, because Eric asked Wolf to show him the changes to Little Red Rooster.

Glyn Johns: We were going to cut Little Red Rooster and Eric said, “Well, I can’t play that.” Wolf looked across at him and said, “You’ve more or less got it.” Eric said, “There’s no way I can do that.” And so Wolf got out a beat-up old f-hole acoustic guitar and he looked out at Eric and said, “Well, I’m going to teach you how to play it. Somebody’s got to do it when I’m gone.” The whole place froze.

Eric Clapton: It was a hairy experience. He came over and got hold of my wrist and said, “You move your hand up here!” He was very, very vehement about it being done right.

Norman Dayron: Of course, Eric knew the song back to front, but the way he put himself out, that’s what really broke the ice on the sessions. It warmed Wolf up, to feel that they really needed him to show them what to do. They couldn’t do it without him.

Glyn Johns: [Wolf] sat and told stories for about two hours while Keith [Richards] sat there in the control room with me one night after the session – a lot of which I didn’t understand because his accent was so unbelievably broad and some of his terminology was quite strange. I just nodded and laughed at the appropriate moment, just to keep him going.

May 4, 1970 : Olympic Studios, recording Wang-Dang-Doodle, Rockin’ Daddy and Poor Boy.

Norman Dayron: Once Bill and Charlie took over the rhythm section, Mick Jagger was there all the time. He was very enthusiastic about getting involved but I really didn’t know what instrument he could play. So, over the course of the sessions, I offered him a variety of different percussion instruments – guiro, maracas, tambourine and triangle.

He had great timing and he did a good job. I remember having a confrontation with Mick Jagger, which I didn’t even know was a confrontation, because I was not well-versed in the subtleties of English societal irony and so on. I think David Bowie and Lennon were there too that night. Mick had his hand on his hip, and his lips stuck out, and he said, “Well, Your Majesty, if you had to go to a desert island and could take only one record with you, what would it be?”

I gave it a little thought and said I would probably take The Greatest Hits Of Ray Charles, because I could listen to that forever. He said, “How boring, what an awful choice.” So I asked what he would take and he mentioned a David Bowie album, I think it was Ziggy Stardust [unlikely - Ziggy Stardust was released two years later - Ed]. It was an awkward moment, but we both ended up laughing about it and, again, it was an ice-breaking moment which bonded us a little better.

May 5, 1970 : Recording at Olympic ends in the early hours of the morning...

Norman Dayron : It was maybe two or three in the morning when we finished up the session and, as my musicians were getting into the cabs, I noticed that Howlin’ Wolf was missing. So I went back into the studio, looked everywhere, called out for him very loudly, and couldn’t find him.

Finally, I looked in the toilets, turned the lights on, and there was a row of wooden stalls with the one at the farthest end with its door closed. I had to bend down and look through the space, about eight inches, at the bottom of the door, and I saw this gigantic pair of size 14 shoes, with the white sweat socks that he always wore. But the cubicle was locked and there was no response when I called out his name, so I had to bang on the door.

I stuck my head right under and I could see him slumped over, evidently unconscious. He had turned an almost white-ish grey colour, his trousers were down around his knees, so all I could do was squeeze into the stall with him, and started to shake him. I was thinking he must have had a heart attack and I was going to go down in history as the man who killed Howlin’ Wolf.

Luckily, he came around quite quickly, and got quite angry. That I should be in the cubicle with him was beyond his imagination. He bellowed out, “What the hell are you doing in here?” That was a big relief, because at least he was alive, and had plenty of energy.

We spent the next eight hours or so in the nearest hospital, where they gave him every imaginable test, but there was nothing to suggest he’d had a heart attack. He had simply passed out. He’d had a long day, he was an elderly man, I think he had been drinking again, so maybe he just nodded out.

As I recall, after he had a few hours sleep in The Cumberland, we went into Olympic, but nothing we recorded that night got used.

May 6, 1970 : Olympic Studios, recording Sittin’ On Top Of The World, Do The Do and Highway 49.

Norman Dayron : One guy who really deserves credit on these sessions is Jeff Carp. He was a brilliant chromatic harmonica player who led a band called the 43rd Street Snipers. I had used him when I produced Muddy Waters’ Fathers And Sons album, and I regarded him as the best young harmonica player around.

Jeff did some wonderful stuff on the London Sessions, and I had got his band signed to Capitol Records, so he had a great future ahead of him. Tragically, he was so elated by what he had achieved at Olympic that he went off on a holiday in the Caribbean with his girlfriend, Scarlet Grey, during which the captain of the ship went insane.

He had taken an animal tranquilizer, PCP, and was chasing people around in a psychotic rage with a big butcher knife. So some people, including Jeff, jumped overboard. Being a New York City kid, he had never learned to swim, and he drowned in 10 feet of water by the dock where the boat was moored. So his album never came out, and there went one of the greatest harmonica players who ever lived, at the age of 18.

May 7, 1970 : Olympic Studios, recording Little Red Rooster, Killing Floor, Worried About My Baby, What A Woman, Built For Comfort, Who’s BeenTalking?

Norman Dayron: That final day was very productive and, with all of the rough edges smoothed out, everybody was locked in and enjoying themselves.

Hubert Sumlin: On Little Red Rooster, Wolf is playing the guitar and I’m right in the background. Wolf ended up playing the slide with a milk bottle but he was in a mess! Because he didn’t have a slide he’d broken the end off and he’d cut his fingers bad, there was blood everywhere!

Norman Dayron: On the CD re-issues, you’ll notice that the section with Wolf showing Eric how to play Little Red Rooster immediately precedes the full band version, but it’s worth remembering that it actually happened several days earlier. I was happy with what we’d achieved but really, there was no celebration for the end of the sessions.

The English musicians did ask me what they might give Wolf as a parting gift and I suggested a fly-fishing rod, because he was a keen fisherman, but I really don’t know for certain if they ever gave him one. We just went back to the hotel, packed up and went home, just as we would have done at Chess at the end of a recording session.

Nobody came to see us off at the airport or anything like that. I made sure that Wolf and the others got on their flights, and then my girlfriend and I went off for 10 days in Spain before flying back to Chicago for mixing and overdub sessions.

When the album came out, initially the American purist blues magazines, which were all run by young white guys, didn’t like the idea of mixing white musicians with black musicians. It really was a kind of racism, they didn’t like white musicians being brought in. They were really snobs.

In later years, I’m pleased to be able to say, people have learned to listen to this album for its musical values and, on that basis, it is now regarded as a real breakthrough moment.

From London Sessions to legendary sessions

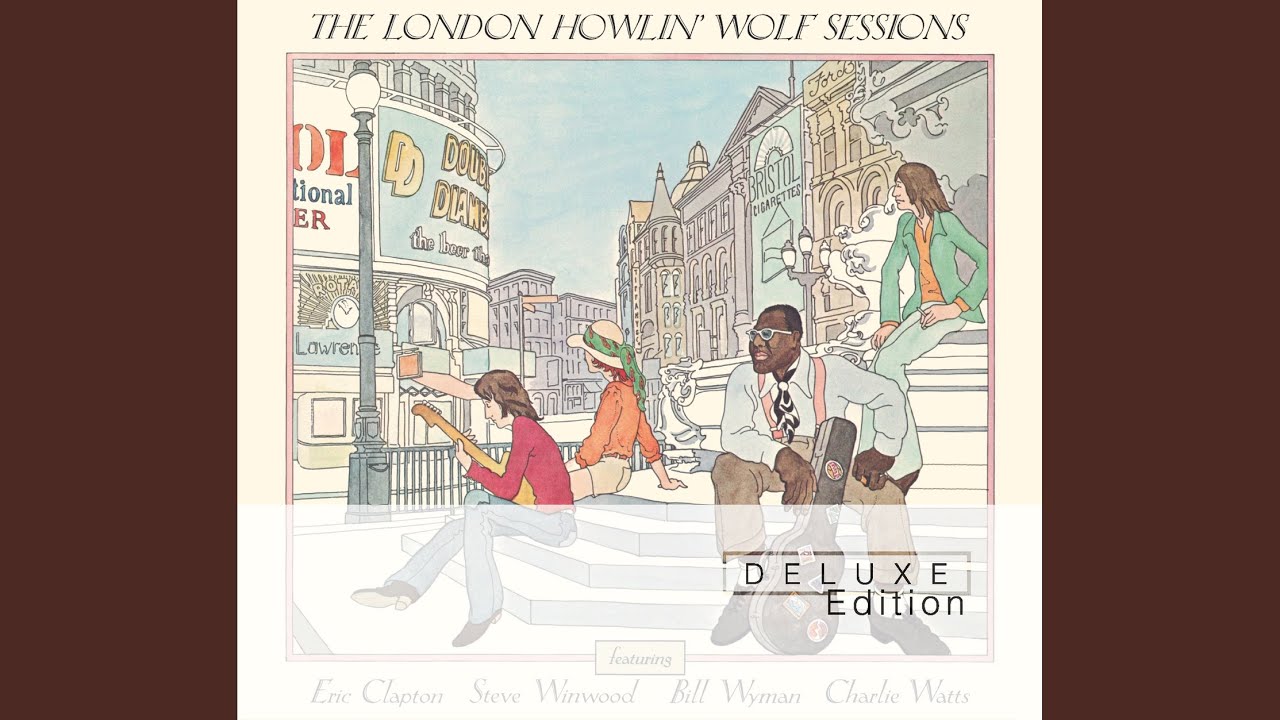

When the London Sessions album was released in August 1971, it achieved producer Norman Dayron’s aim of dramatically improving Wolf’s profile by becoming his first – and last – album to reach the Billboard Top 100 Albums chart.

Despite the participation of sundry Stones and Beatles, it disappointingly made no impact whatsoever on the British albums chart. Peaking on the Billboard chart at a none-too-exciting No 79, which would have been disappointing for almost any of Wolf’s white rock’n’roll sidemen, it was nevertheless a leap forward for Wolf and the blues in general.

Indeed, it did well enough that in February 1974 Chess released London Revisited, a rag-bag cash-in project built around the original’s success, consisting of three out-takes from Olympic Studios plus a few leftovers from Muddy Waters’ 1971 London sessions.

It also spawned several similar London-based collaborations, the most memorable being by Muddy. However, as Dayron himself admits, The London Howlin’ Wolf Sessions was not welcomed with open arms by the entire blues community. Just as Wolf himself had expressed reservations about the notion of playing with white rockers, and Clapton had wondered out loud why he was needed at the sessions, so the blues purists of the critical fraternity were not best pleased by the collaboration.

The era of super-sessions had been ushered in back in July 1968 with the Mike Bloomfield, Al Kooper and Steve Stills album Super Session, a spontaneous set of live-in-the-studio jams by hot young players, all of them blues oriented, all of them white.

It’s worth remembering though that Chicago’s pioneering Paul Butterfield Blues band was a mixed-race outfit from the get-go in 1963. Gary Von Tersch’s Rolling Stone review of London Sessions was kinder than most of the blues mags, rating it Wolf’s “best album in years”, hailing it as “among the most successful of these black-meets-white get-togethers” and describing the contents as “13 Blues-stellar performances”.

The UK’s pop weekly Disc, however, wasn’t so convinced. The whole of side one was dismissed as “disappointing, all a bit samey” and the final comment was, “Don’t expect too much.” Bill McAllister’s review in Record Mirror was headlined ‘Wolf without teeth?’ and summed it up as “not an exceptional album”.

But times and opinions change, so by 1992 the Rolling Stone album guide was giving it four stars and calling it “a good late collaboration”. Come 1994, Robert Santelli’s Big Book Of The Blues devoted almost three pages to Wolf’s recorded output, and included London Sessions as “essential listening”.

Evidence that interest in the London Sessions has never since waned came in 2003, when the two-disc Deluxe Edition put together by Universal sold well enough to hit No Six in the Billboard Blues Albums chart.

The controversy, however, continues to rage. The redoubtable Kub Coda on the All Music website pans it, saying, “while it’s nowhere near as awful as some blues purists make it out to be, the disparity of energy levels between the Wolf and his UK acolytes is not only palpable but downright depressing”.

Was it a truly great album? It certainly wasn’t Wolf at the peak of his powers. We know from contemporary reports, for example, that Norman Dayron had to hold lyric sheets up for him, and sometimes even whispered lines in his ear just before he sang because Wolf couldn’t remember his own lyrics.

His voice was a little less powerful, and he wasn’t entirely comfortable with his accompanists, but the end result – listened to at a remove of some 40 years – still cooks, simmering with the same air of menace that made his earlier classics so gut-wrenchingly powerful.

Johnny is a music journalist, author and archivist of forty years experience. In the UK alone, he has written for Smash Hits, Q, Mojo, The Sunday Times, Radio Times, Classic Rock, HiFi News and more. His website Musicdayz is the world’s largest archive of fully searchable chronologically-organised rock music facts, often enhanced by features about those facts. He has interviewed three of the four Beatles, all of Abba and been nursed through a bad attack of food poisoning on a tour bus in South America by Robert Smith of The Cure.