Lone Star were tipped for stardom: then came booze, bongs and Scientology

Welsh wizards Lone Star were loved by Jimmy Page and had connections to Queen and Elton John... but wherever it could go wrong, it did

“We were the right band at the wrong time,” claims Lone Star guitarist Tony Smith. “We lost popularity overnight when punk rock exploded on to the scene.

“I remember my girlfriend taking me to the Blitz Club in London’s Covent Garden, when it was all kicking off with Steve Strange and everything. We waltzed in, and there’s me with my long blond hair and white flared trousers. Rusty Egan was the DJ. He said: ‘Lone Star? Yeah, that’s the band that punk killed.’ Good God, how right he was. In 1977, Britain was no place to be if you were in a rock band.”

But was it really that simplistic? Did the gob-addled advent of punk truly curtail the career of one of the most promising British heavy rock bands of the 70s? Or was there more to it than that?

Of course, it didn’t help that Lone Star parted company with their lead singer, chief songwriter and – some might say – talisman shortly after the release of their debut album.

It didn’t help that that same singer had a nervous breakdown after his girlfriend was rendered paraplegic due to a car crash.

It didn’t help that, despite being managed by Abe Hoch, former right-hand man to Led Zeppelin’s Peter Grant, Lone Star never toured America.

It didn’t help that Tony Smith’s fellow guitarist, Paul Chapman, was in two groups at the same time: Lone Star and UFO.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

It didn’t help that Lone Star signed “the worst record deal ever”.

And it didn’t help that some of the members of Lone Star were Scientologists…

Lone Star’s story begins in Cardiff, South Wales, in 1975. Vocalist Kenny Driscoll and guitarist Tony Smith had just returned from Canada where they’d been playing shows with their semi-pro band Iona. Both were keen to take their musical ambitions to the next level. Driscoll, in particular, had “a complete vision for a bold new adventure”.

The pair brought in bassist Pete Hurley and drummer Dixie Lee and began rehearsing in a village hall in Rudry, just north of Cardiff. “Paul Chapman started turning up – we didn’t really need another guitarist but he kind of wormed his way in,” says Driscoll. “Then I went back to Canada and found Rik Worsnop, the keyboard player.”

“I’d been playing with Kenny on and off since I was about thirteen,” counters Chapman. “We had a band way before Lone Star, called Zebra Leader, so named because it sounded a little bit like Led Zeppelin. I was eighteen, just pushing nineteen, when I bumped into Pete Hurley and we talked about getting a serious band together. I said: ‘There are really no decent singers in Cardiff except for Kenny…’ That’s how Lone Star started to take shape.”

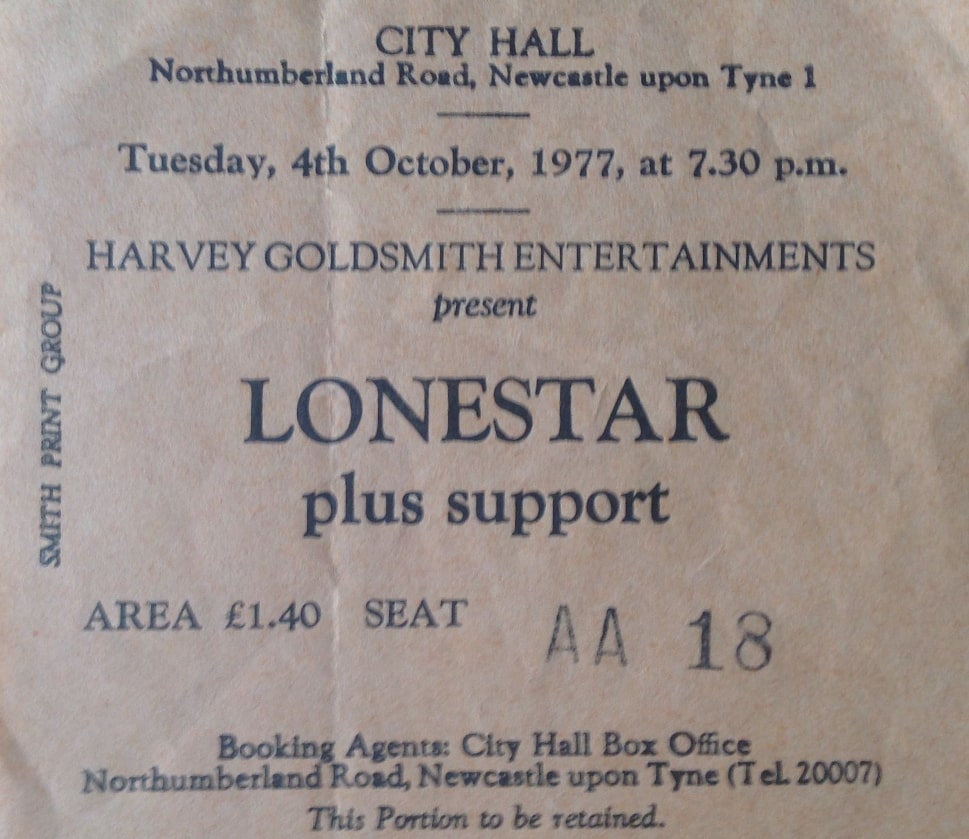

Whatever the truth about the band’s genesis, what is for sure is that the six fledgling members scraped together £300 and recorded a five-song demo tape – known as the Acorn Sessions – in a studio in Woodstock, near Oxford.

Driscoll explains: “My influences were Free, Bad Company and Jethro Tull. I used to love a song by Blodwyn Pig called See My Way. It was so beautifully structured. I decided to see if I could make my own arrangement of it. So I chopped it, changed it and transformed it into something completely different. That gave me the idea to tackle The Beatles’ She Said, She Said. I thought I’d go here, there and everywhere with it.”

Besides the radical Mop Tops cover, Lone Star’s tape included the tracks A Million Stars and Flying In The Reel, which would appear on the band’s debut album, and Hypnotic Mover, which would be on the follow-up. The remaining song, Shotgun Rambler, didn’t make it beyond the demo stage.

Original Lone Star manager Steve Wood takes up the tale: “I had a friend from Cardiff who was a roadie for Osibisa. He told me about this local band who sounded amazing. He sent me Lone Star’s demo and I was knocked out by it, especially by their version of She Said, She Said. I’d never heard a Beatles song done in such an ambitious way before.”

Wood was working in London as a promotions assistant for Tony Stratton-Smith, boss of Charisma Records. “To this day, I don’t know how I got the job,” he chuckles. “I think ‘Strat’ must have fancied me; I was only seventeen years old. But what I really wanted to do was to manage a rock band; I wanted to be like Led Zeppelin’s Peter Grant. I just saw a life of sex, drugs and rock’n’roll ahead of me.”

“Steve came down to Cardiff to check us out,” says Driscoll. “He loved our music because we were very advanced at that time; we were doing virtually the whole of the first Lone Star album already. I told him: ‘You can manage us if you get us a record deal.’”

Aiming high, Lone Star decided that Led Zeppelin’s record label, Swan Song, would be their dream ticket. “Zeppelin were our benchmark,” says Smith. “And somehow we got an appointment to see Peter Grant in Munich, where they were recording the Presence album. This would’ve been late 1975. We went with our demo tape to Heathrow, but we did a really irresponsible thing and got smashed on the way there. We drank too much wine and missed the plane.”

They caught an alternative flight from Gatwick but arrived in Germany too late for their meeting with Grant. However, while languishing in a hotel lobby they bumped into Zeppelin tour manager Richard Cole. Taking pity on this “scruffy bunch of Welsh oiks”, Cole invited them to meet Jimmy Page at Musicland Studios.

“They put on our demo through the big speakers,” says Smith. “I was shitting myself, wondering if Jimmy was going to like it. But from the first track, he was all ears. Pretty soon he was so into it he started headbanging. So I joined in. Imagine, me and Jimmy headbanging to Lone Star’s demo!”

“We also met Peter Grant’s assistant, Abe Hoch,” reveals Driscoll. “He said if we signed [to Swan Song] he’d have to shelve us for eighteen months, maybe two years, because they had Presence coming out, they had a new Bad Company album, they’d just signed Maggie Bell…”

Back in Britain, “Dave Dee from Atlantic Records was very interested in us; there was kind of a bidding war going on,” says Wood. “John Peel and Tony Wilson [producer of Alan Freeman’s Radio One rock show] had a lot to do with it; they gave us multiple sessions.

“We signed to CBS because they offered us a worldwide deal. But it was actually the worst record deal ever. I was young and naïve. They used this very big word and I didn’t know what it meant: cross-collateralisation. I was too embarrassed to ask, so I just said okay. It basically meant CBS controlled everything: merchandising, publishing, record sales… the booking agent was in-house as well. I just signed it because I wanted to get going. I’ll never forget what Obie [CBS head Maurice Oberstein] said when I asked him for a bunch of money to take Lone Star to America: ‘Sorry, kid, that’d be like giving a loaded gun to a child.’”

“CBS sent a limo down to Cardiff; there was a Daimler outside my house with a fully stocked bar,” Smith remembers. “Like fools we piled in, got drunk, drove down the M4 to London and inked the deal. It looked good at first, but I couldn’t help but notice they’d put us on a wage of thirty pounds a week, which even then was rubbish.”

In the summer of 1976, Lone Star flew to Sweet Silence studios in Copenhagen to record their first album with Queen producer Roy Thomas Baker. “CBS really saw a winner here and Roy had done Bohemian Rhapsody, so they threw the kitchen sink at this thing,” says Smith.

“We were staying in a hotel next to a place called Christiania Land,” says Wood. “It was a commune for Hells Angels, hippies, prostitutes and drug dealers. But it was left alone by the police. That had a lot to do with what was going on with that first record. Everybody was completely blotto. The smoke clouds in that room were legendary. There was a machine full of Carlsberg Elephant Beer. Everybody was out of their minds. It was an absolute madhouse, making that record.”

“We had a tour with Ted Nugent booked, we were running out of studio time and I still had to do my lead vocals,” says Driscoll. “It was one of the hottest summers on record and there was no water in the studio, only a beer machine.”

And it was a machine that dispensed a beverage almost as strong as Special Brew, even though “it tasted just like normal beer”, according to Driscoll.

“To cut a long story short, I started that album at about 2.30 in the morning and finished it three hours later. And it was terrible. I could have done a million times better. I was drunk. And they wouldn’t let me re-do my vocals. One of the engineers said: ‘It’s only a first album, no one listens to first albums, it’ll be forgotten in no time at all.’ To be absolutely honest, it was not a shadow of what I could have done. A bit of a disaster, really.”

Lone Star’s self-titled debut was released in August 1976 and remains one of the great undiscovered – and, as a consequence, under-appreciated – British heavy-rock albums of all time. Opener She Said, She Said injects the John Lennon chestnut with a performance-enhancing drug and sends it into a different space-time continuum. Tracks such as Flying In The Reel and Lonely Soldier mix the grit of UFO with the grandeur of Queen, and combine the songwriting nous of both.

The progressive cosmology of the album’s central trilogy of songs – Spaceships, A New Day and A Million Stars – likely betrays the Scientology fandom of certain band members. Illusions, meanwhile, is the best ballad Led Zeppelin never recorded. Oh, and Kenny Driscoll’s vocals? Remarkably, they’re absolutely fine – powerful, heartfelt and with an endearing fragility à la Widowmaker-era Steve Ellis.

The plaudits came in thick and fast. “If Lone Star don’t make it, I’ll saw off my legs and send you all a piece,” gushed John Peel. Fellow supporter Alan Freeman enthused: “Lone Star are going to be incredibly mighty.” A certain Sounds journo called Geoff Barton, while mildly critical of Roy Thomas Baker’s over-the-top production, proclaimed: “Beneath the glitter and the shiny chrome plating, Lone Star must be one of the best UK bands to emerge for some time.”

“We were grateful for the opportunity to work with Roy but I don’t know if it was the best marriage,” Smith reflects. “Some people say the demos and the Radio One sessions are better, because they’re not over-produced. The bad thing about it was, for some reason CBS only decided to print 50,000 copies of this album that they’d invested all this money into. It sold out in three weeks – it went into the chart at number seventy-six. Next week it went higher, then it went higher still, then it was… nothing. Overnight it just disappeared.”

In these days when a handful of digital downloads can get you a top-five position, it’s a sobering thought that in 1976 physical sales of 50,000 was regarded as a failure.

To compound Lone Star’s problems there was plenty of inter-band strife bubbling underneath the surface. For starters, Kenny Driscoll and Paul Chapman weren’t exactly seeing eye to eye.

“Paul messed up the band,” Driscoll offers. “Before he got involved it was so much better. He cluttered everything up. It was all nicely structured, and when he arrived we had to think of things for him to do. He actually did nothing. He was always very difficult. At live shows he blasted everybody out, his greasy hair flying everywhere, disregarding everybody else in the band. He did that when we were on The Old Grey Whistle Test. I had to push him out of the way of my mic in the end.”

“Kenny had a beef with me,” Chapman admits. “He used to say: ‘I have a feeling you’re invading my space.’ What the hell does that mean? We were at loggerheads all the time.”

But Driscoll had other, more telling matters on his mind. Just before Lone Star entered the studio to record their demo, he and his girlfriend, Linda, were involved in a serious car accident. Driscoll was pretty smashed up – his face was scarred and he’d broken his collarbone – but Linda was paralysed from the neck down.

“That very had a bad mental effect on Kenny,” says Wood. “He had demons because of the accident. His ambitions were dampened. He became a very difficult person to work with. He started drinking heavily, he used to get violent… he was in a very bad place.”

“I was living with Linda and we had a two-year-old baby,” says Driscoll. “Everybody else in the band was having a whale of a time, enjoying the spotlight, and I was having a nervous breakdown. I became very withdrawn and I wouldn’t speak unless I was spoken to. Linda was absolutely the most beautiful girl I had seen in my life… I’m looking at a picture of her now. After the accident they shaved off her hair and put these spikes in her skull, then they attached weights to them to keep her head steady. Her injuries were so serious, a normal neck brace wouldn’t have worked. She wanted to die. And, eventually, she did.”

Whenever there was a break from touring or recording, Driscoll would rush to be at Linda’s hospital bedside in Cardiff. But ultimately the pressure became too much to bear. “We were on tour with Mott and I said to the guys: ‘I can’t do this any more, my head is in turmoil.’ I needed a month, six weeks off to get my perspective back. But they said: ‘No, if you’re not prepared to carry on, we’re going to get a new lead singer.’”

“It was a bad time in Kenny’s life,” says Smith. “I felt very sorry for him, obviously. But he also wanted to be Mr Everything. He wanted the band to play solely his songs and be a controlling influence. That caused friction because the other members wanted their input too.”

While searching for a new lead singer, Lone Star underwent a change of manager. Steve Wood was sidelined, and Abe Hoch – who had recently left Swan Song – snatched the reins.

As Wood recalls: “There’s a knock on my door, and this guy is standing there with his chauffeur. ‘Hey, kid, are you Steve? I’m Abe Hoch. I wanna manage your band with you.’ He looked like The Fonz from Happy Days. ‘I’ve just left Swan Song, I’ve done a deal with John Reid, we’ve got offices in Mayfair and we’re called ADG – Artist Development Group. We manage Queen and Elton John and we’d like to manage Lone Star. You can stay where you are but I’ll make all the decisions.’ I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. So that was it, we were now in the rarified company of Queen and Elton John.”

“Bringing in Abe Hoch was a mistake,” Chapman says. “Steve Wood was sideways-promoted, and people were brought in who we’d never met; shifty-looking characters. Steve really didn’t have much of a say any more.”

Abe Hoch was instrumental in choosing Kenny Driscoll’s replacement, as Tony Smith explains: “There were two guys in the running: John Sloman, who was in a Cardiff band called Trapper, and Lyn Phillips, another Welsh singer, who had a great rhythm-and-blues voice. Hoch had a definite preference for John. So much so that he went over to poor Lyn and said: ‘I don’t like you and I don’t like that Joe Cocker type of voice either, that’s not for this band. Look at John Sloman, look at him over there. He is The Bells Of Berlin’ [the title of the opening track on Lone Star’s second album, Firing On All Six]. We were just cringing at this loudmouth American putting our friend down.”

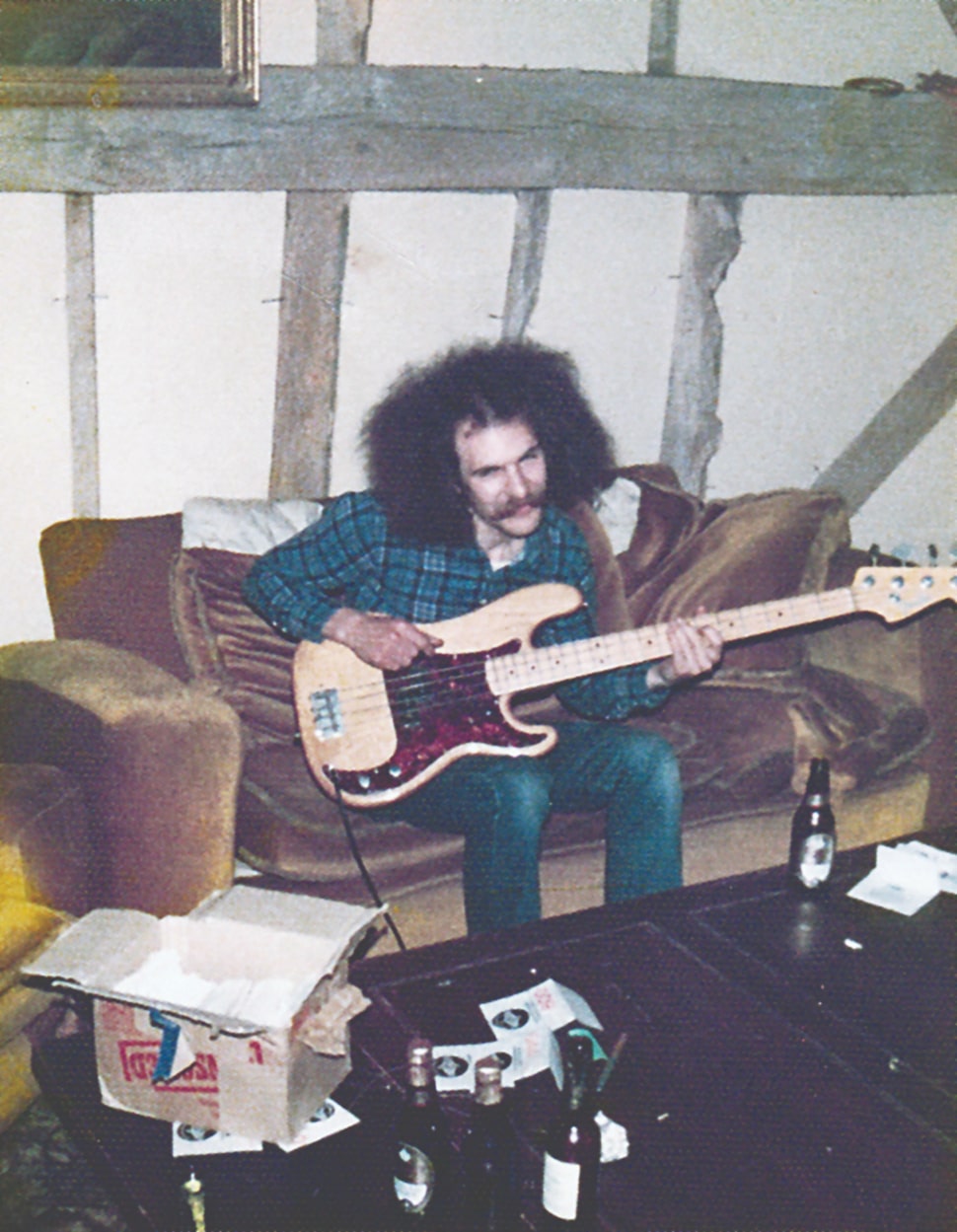

As was customary for rock bands of the 1970s in search of inspiration, Lone Star decided to get their heads together in the country. With new singer Sloman in tow, they decamped to Ridge Farm in the sleepy village of Rusper, West Sussex to work up songs for their second album.

“We all went down there, and the idea was to write a new record,” Wood recalls. “But the band just started smoking masses of dope in bong pipes, and got into these extended jams. It turned into Pink Floyd or funk jams. It was really weird. There was an upstairs area in the barn they were rehearsing in. Pete Hurley had an extended lead attached to his bass so he could he could play up there while lying down, he was so stoned.

"It was an unbelievable situation. There were women, drugs… nobody was doing any work. They lost sight of their goals. One day the record company came down, unannounced, at three in the afternoon to check how their investment was doing. Everybody was asleep. And they were horrified by the new songs when they heard them.”

But somehow Lone Star pulled it out of the bag. Firing On All Six, released in August 1977, while not as tightly focused as its predecessor, is still one mightily accomplished record. The quality of the musicianship is breathtaking, and the record benefits from a more straightforward production by Gary Lyons, Roy Thomas Baker’s engineer.

The two best songs are left-overs from the first-album sessions – Hypnotic Mover and the aforementioned The Bells Of Berlin, an elegiac tale of the city’s former east-west divide – but tracks such as The Ballad Of Crafty Jack and All Of Us To All Of You are no slouches either, inviting comparisons to Led Zeppelin and Queen at their majestic best.

There’s a funky edge, too: close your eyes and Rivers Overflowing and Time Lays Down could be Glenn Hughes showboating with Deep Purple. On the downside, Sloman’s lyrics are fantastical and flowery, bordering on the nonsensical. And the ballad Seasons In Your Eyes – complete with strings arranged and conducted by Jeff ‘War Of The Worlds’ Wayne – is more cloying than a crate of crèmes brûlées. But you can’t have everything.

Firing On All Six cracked the UK Top 40, reaching No.36. But the times they were a-changing. With punk rock in the ascendancy, Lone Star’s loon-panted posturing suddenly looked terribly old-fashioned. Howls of derision were hurled in the band’s direction, Paolo Hewitt of the NME memorably sneering that they were “two years out of date”. Only Sounds kept the faith, insisting firmly that Lone Star were “going to make it this time”. (Albeit with the added proviso: “‘Hrmph!’ says cynical editor.”)

Oh, and John Sloman’s resemblance to Robert Plant didn’t go unnoticed either.

“The Plant comparisons knocked John’s confidence a bit,” Chapman concedes. “In fact he got nailed to the wall. It was a tall order for him to step in and take over. In retrospect, it was a bit of a mistake.”

“John was never Robert Plant,” insists Smith. “If you listen to his voice, he was more like Ian Gillan. But he was only nineteen when he joined us, and he really took the Plant criticism to heart.”

Looking back, Sloman’s critics might have had a point. YouTube footage of Lone Star performing a BBC In Concert session shows the frontman (who would later join Uriah Heep for a single album, 1980’s Conquest) preening in a very Percy-esque fashion. There’s also a wince-inducing moment when Sloman clears his throat and coughs during She Said, She Said’s big vocal build-up. (Or maybe he was being ironic, who knows?)

Shortly after the release of Firing On All Six, Lone Star played the Reading Festival alongside such established names as Thin Lizzy, the Sensational Alex Harvey Band and Golden Earring. They even headlined London’s legendary Rainbow Theatre, before mysteriously stepping down a peg and embarking on a British tour supporting Mahogany Rush, the band led by Canada’s frazzled Jimi Hendrix impersonator Frank Marino.

“Punk had started and the writing was on the wall,” says Wood. “It was absolutely on the wall. We did it [the Mahogany Rush tour] with full lights and sound, but the age was changing. Long hair and Les Paul guitars were definitely not what they used to be.”

So we arrive back at the question posed at the beginning of this feature: did punk rock kill Lone Star’s career?

“Absolutely it did,” Wood responds emphatically. “Overnight, rock wasn’t cool any more. Everything was safety pins and bondage pants. And it murdered the band.”

“We definitely lost popularity when punk hit,” agrees Smith. “We had great reviews in the first year [1976] but then we became a subject of derision. We’d signed over our souls to CBS and the record company just switched off. We’d gone from being in-favour to old-fashioned overnight. It was terrible.”

Paul Chapman and Kenny Driscoll, however, have different views.

“In 1977 [UFO guitarist] Michael Schenker disappeared, and I went over to America and did the Lights Out tour. The album was number twenty-four on the Billboard chart,” says Chapman, who’d had previous flirtation with UFO from ’74-75 as part of a twin-guitar line-up with Schenker.

“I was in both bands – Lone Star and UFO – at the same time, flying back and forth, in the lull before Firing On All Six was released. UFO played Soldier Field in Chicago with Peter Frampton, and I was like: ‘Holy shit!’ I wanted to move to America with Lone Star. We could’ve been huge out there. But then I found out that certain members were just content to stay in Wales. That wasn’t what we had talked about when we formed the band. I knew at that point there was going to be a rift.”

“Punk had nothing to do with Lone Star’s career going down the pan,” Driscoll states firmly. “To start with, there was a huge market for us in America. But another big problem was that certain members were into Scientology [a body of religious beliefs and practices created in 1954 by American science-fiction author L Ron Hubbard]. It caused enormous arguments. Dixie [Lee, drums] used to talk to dogs – because they [Scientologists] call animals Degraded Beings. Dixie used to say: ‘Hello DB, wouldn’t you like to have hands like me instead of claws?’ Needless to say, our record company didn’t like it.”

“It was mainly Tony and Dixie who were into Scientology,” says Wood. “We used to have these interminable conversations about aliens. It was insane. You might think their rock’n’roll lifestyles and Scientology wouldn’t mix… Frankly, I don’t know how they rationalised it in their own brains.”

“We were fully into it [Scientology],” Smith admits. “I’m sure we must have looked like right knob-heads to the rest of the band. If we did, we didn’t care. We were just convinced that it was the right way to look at the world, the universe, everything. You could say I have a sort of distance from it now. But at the time we were deadly serious about it.”

“After Lone Star folded I helped Dixie get a gig with Ozzy Osbourne, when he was putting the Blizzard Of Ozz band together,” says Chapman. “I said: ‘Whatever you do, don’t start going on about Scientology.’ Dixie lasted two weeks. One day he said something like: ‘If you have a problem, you screw it up in a ball like a piece of paper and throw it out the window.’ And Ozzy said: ‘You’ve got a problem now, you’re fired. So screw that up and throw it out the fucking window.’ And that was the end of that.”

Lone Star retreated back to Cardiff to write songs for a third album, but “they were stoned all the time”, says Wood. “All the ambition had left. The get-up-and-go had gone.”

“At the end of October 1978 I got a call from [UFO bass player] Pete Way,” says Chapman. “He said: ‘Schenker has gone weird again. Would you consider joining us full-time and moving to Los Angeles?’ I said: ‘I’ll be there yesterday.’ And that was that as far as Lone Star was concerned.”

“Lone Star’s demise hurt me emotionally because I’d spent my whole life wanting to be a success in the music business and I’d failed,” says Wood. “I couldn’t even listen to their music for years. It was very painful. It felt like part of me was missing, I believed in it so much. When I first heard She Said, She Said and A Million Stars I thought, oh my God, this is gold. The quality of the songwriting, the guitar playing, the earthiness of it… everything. But it was not to be.”

What the Lone Star members did next

Lone Star manager Steve Wood now works for Paul Geary Management in Los Angeles, where he handles the careers of Steel Panther, Myles Kennedy, Kings Of Chaos, Glenn Hughes, Joe Perry and more.

Guitarist Paul Chapman enjoyed a successful stint in UFO before joining Pete Way’s band, Waysted. He moved to Florida to work as a guitar tutor, later joining southern rockers Gator Country, featuring members of Molly Hatchet. In 2000 Chapman released (via the Zoom Club label) Riding High – The Unreleased Third Album, supposedly containing songs written for the aborted follow-up to Lone Star’s Firing On All Six. In 2015 he embarked on a US tour as guest guitarist with Sweden’s Killer Bee. He died in 2020.

Guitarist Tony Smith joined female-fronted band Screen Idols, then moved to Los Angeles and formed Lion with ex-Tytan vocalist Kal Swan. Now back in Wales, he plays the club circuit with his covers band The Daggers.

Vocalist John Sloman joined Uriah Heep for 1980’s Conquest album before forming John Sloman’s Badlands with guitarist John Sykes in ’82 and guesting with Gary Moore on the Rockin’ Every Night – Live In Japan album. Sloman went solo in the mid-80s and has released several albums in various musical styles. His most recent, Two Rivers, was released by Red Steel Music in 2022.

Drummer Dixie Lee toured with Wild Horses in late 1978, then teamed up with John Sloman in the short-lived Pulsar. Lee was also in an early version of Blizzard Of Ozz and briefly joined NWOBHM band Persian Risk in late ’83. He retired due to health problems, and died in 2022.

Bassist Pete Hurley plays with a band called the Red Hot Pokers, who in a previous incarnation backed Van Morrison and Jerry Lee Lewis. He also works with Welsh-language artists including Meic Stevens and Geraint Jarman.

Keyboard player Rik Worsnop returned to Canada to pursue a career as a software developer.

In 1979 original frontman Kenny Driscoll put together a new version of Lone Star but his efforts were thwarted by a CBS lawsuit. The following year he hooked up with Gary Moore for his Live At The Marquee album. He now plays Welsh clubs with the Kenny Driscoll Band.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 224, in May 2016.

Geoff Barton is a British journalist who founded the heavy metal magazine Kerrang! and was an editor of Sounds music magazine. He specialised in covering rock music and helped popularise the new wave of British heavy metal (NWOBHM) after using the term for the first time (after editor Alan Lewis coined it) in the May 1979 issue of Sounds.