A beginner's guide to Cat Stevens in six essential albums

Despite a string of hits including Matthew & Son, I'm Gonna Get Me a Gun and Wild World, Cat Stevens was always a reluctant star. These are his best albums

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

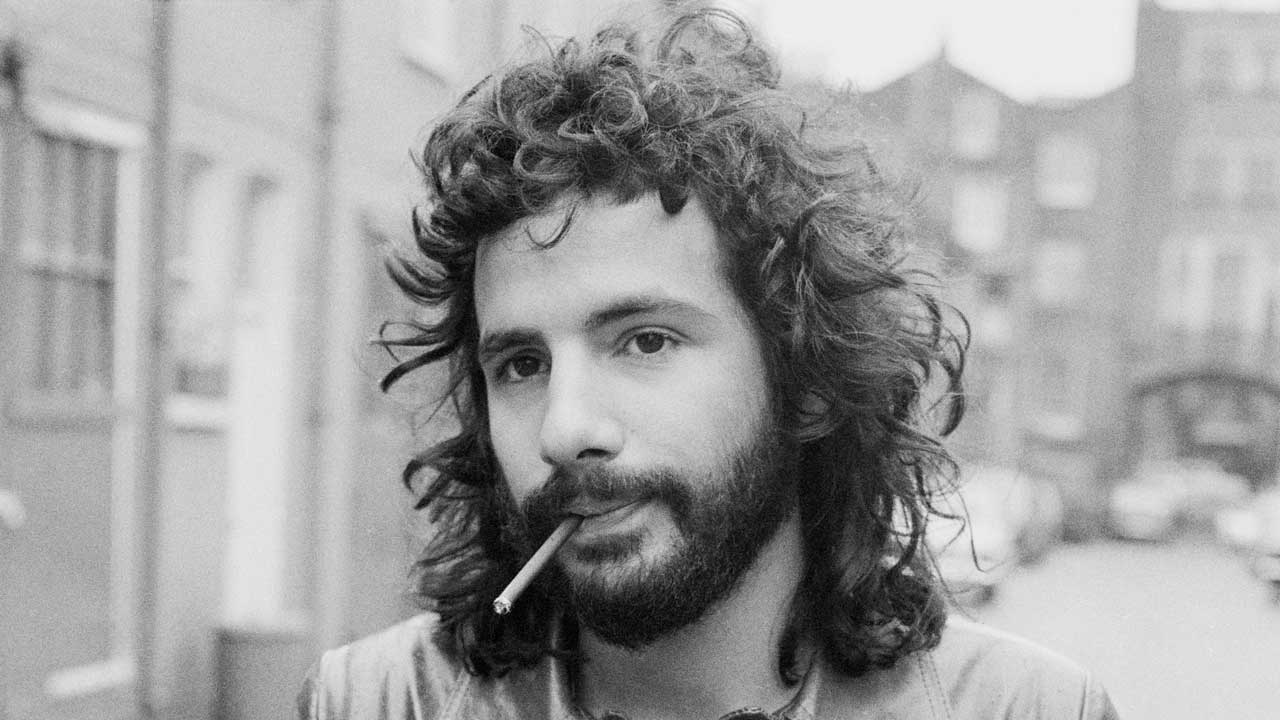

Cat Stevens rode the crest of the singer-songwriter wave through the early part of the 70s, alongside the likes of James Taylor and Carole King. He played to 15-20,000 people a night at arenas around America. He sold millions of records.

Hip cult heroes like Nick Drake, John Martyn and Richard Thompson (all of whom were signed to Cat’s record label, Island Records) may have been the darlings of the rock media, but their total combined sales came nowhere near one Cat Stevens album.

Here are the six albums you need to know.

Cat Stevens may have complained that he was a ‘puppet’ on his first album, but he was also a novice and Mike Hurst’s production gives his precocious songwriting a commercial pop platform – even though the arrangements were occasionally misguided.

Stevens had already proved his credentials with I Love My Dog, Matthew & Son and Here Comes My Baby (which was a hit for The Tremeloes in Britain and America), but even so filling an entire album with his own songs was an exceptionally bold move for the time, particularly for someone whose name was not Lennon or McCartney.

Returning after an absence of two years after being stricken with tuberculosis, Cat Stevens starts his career anew with an album of disarmingly personal songs that are a world away from his previous pop star persona.

The sweet romance of Lady d’Arbanville is a deceptive opening for an album that questions his earlier celebrity (Pop Star) and lifestyle (Trouble) and then hints at a deeper, more fulfilling alternative (I Think I See The Light, Fill My Eyes). The sparse arrangements and the simple, direct vocals struck a chord with many who had similar thoughts at the start of the 70s.

This is the quintessential Cat Stevens album, where the tentative quest of Mona Bone Jakon blossoms into a journey of discovery fuelled by faith and optimism, whether he’s wondering Where Do The Children Play, looking for a Hard Headed Woman, plotting the route on Miles From Nowhere or simply On The Road To Find Out.

His sense of melody and distinctive, catchy hooks culminates in the sublime Wild World. He defines the generation gap with warmth and passion on Father & Son and sums up his own sentiments on But I Might Die Tonight: "I don’t want to work away/Doing just what they all say."

His third album in 15 months, Stevens begins to tighten up the message, notably on the holy roller that is Peace Train and the evangelical Changes IV, while in The Wind he wonders where the journey is leading. He also refines his sense of melody by adapting the hymn, Morning Has Broken, and it all culminates with the exquisite Moonshadow, arguably the most affecting, poignant song he ever wrote.

The balance between his spiritual search and his musical instincts remains perfectly poised and eminently satisfying to anyone who had bought either of his two previous albums, while still capable of luring new converts.

A sense of urgency creeps into Catch Bull At Four that mirrors Cat Stevens’s growing sense of purpose, typified by the single-minded determination of Can’t Keep It In. The spiritual quest he’s been developing takes on a more overtly religious tone, and the rhythms and arrangements are more intense.

He’s also starting to spread his musical net wider, even absorbing some of his Greek roots on O Caritas. While the album is less fluid than before, he retains the power to engage your attention, particularly on the opening track, Sitting, where the lonely nature of his odyssey becomes vividly apparent to the listener.

A diversion on the road to fulfilment that succeeds against the odds. Jettisoning his band and long-time producer Paul Samwell-Smith, Stevens heads to Jamaica with a bunch of session musicians, including brass and string players plus a female backing trio.

The result could have been a disaster but instead the changes freshen up his musical approach. The 18-minute Foreigner Suite provides a new context for his restless ideas, while the soul-tinged elegance of Later shows that his style can adapt to different surroundings. The message is still the same though: as he sings on The Hurt: "Love is the ultimate truth."

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Hugh Fielder has been writing about music for 50 years. Actually 61 if you include the essay he wrote about the Rolling Stones in exchange for taking time off school to see them at the Ipswich Gaumont in 1964. He was news editor of Sounds magazine from 1975 to 1992 and editor of Tower Records Top magazine from 1992 to 2001. Since then he has been freelance. He has interviewed the great, the good and the not so good and written books about some of them. His favourite possession is a piece of columnar basalt he brought back from Iceland.