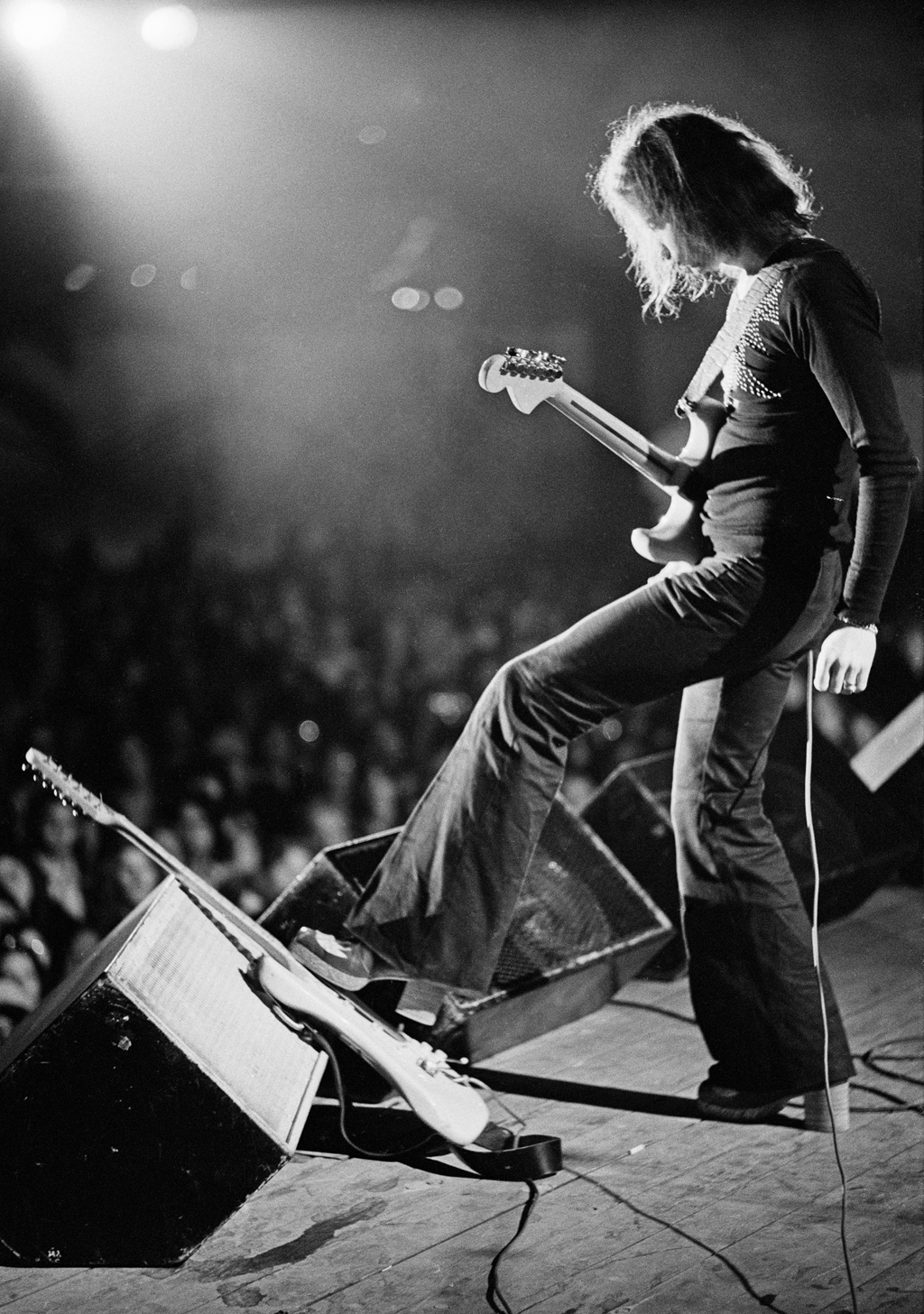

The Real Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame: Ritchie Blackmore

In 1975, just after he left Deep Purple, the guitarist gave a series of interviews about his inspirations and his time in the band. This is what The Man In Black had to say.

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

On April 18, Lou Reed, Green Day, Ringo Starr, Joan Jett and others will be inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame, joining everyone from The Beatles, the Stones, Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd and The Who to Kiss, Metallica, ZZ Top and, er, ABBA. But what about all the bands this US institution has overlooked, ignored or wilfully snubbed over the years? The giants and innovators of rock, prog, punk, blues and more who weren’t deemed important enough, cool enough or American enough to warrant entry through those hallowed portals. Nearly 50 years after forming, Deep Purple are the greatest band not to be in the official Hall Of Fame. They are one of a diminishing handful of bands who formed in the late 60s who are still active today, who are not content to rest on their laurels and who still exist in a meaningful and creative way. While many of their peers are content to play the chicken-in-a-basket circuit – their tour posters emblazoned with monochrome mug shots of how they looked back in their bushy-tailed heyday – Purple have matured like a fine, expensive wine (a Sweet Burgundy, as their former guitarist, the late, great Tommy Bolin, might have it). From 1968’s Shades Of Deep Purple to 2013’s NOW What?!, Purple’s passage through time resembles a mountain range of breathtaking highs and turbid lows. Via a series of interviews with every key member past and present, we celebrate Purple’s extraordinary, multi-decade career. We highlight the radically different personalities of the musicians who have impacted on the band, and marvel at how these contradicting characters were able to gel musically. We examine the mysterious – and occasionally devious – workings of this at times most volatile of bands. We analyse the contributions of alleged bit-part players including Nick Simper, Joe Lynn Turner and the aforementioned Bolin. Plus much more besides. This is Deep Purple dissected, deconstructed and laid bare. (Oh, and we only mention Smoke On The Water once.)

Who were your main influences?

My first influence, believe it or not, was Tommy Steele. I saw him jumping about with a guitar around his neck and I thought, that’s what I want to do. So I picked up the guitar and started prancing about like he did. Then I found out more about guitarists and started to emulate certain players. I think the first one was Hank Marvin of The Shadows. I used to play Apache, which he recorded as a single with The Shadows. Then I heard about this guitarist who was living in the Hounslow area, where I lived at the time, and his name was Jimmy Sullivan. When I saw Jim I thought it’s either a case of giving up or trying to compete. I was always trying to steal his guitar solos.

_Any other early idols? _

Les Paul, Django Reinhardt, Wes Montgomery, Cliff Gallup who used to play with Gene Vincent, Scotty Moore who played with Elvis Presley. But at the moment I don’t have so many idols who play guitars. I prefer listening to violinists, cellists. For many years I’ve been tending towards classical, although I don’t play classical guitar in the accepted orthodox manner. I also listen a lot to medieval music. I’ve taken up playing cello. Trying to, anyway. Even so, I still consider myself to be more or less a rock guitarist. Playing rock is definitely a challenge because of the limitations involved, such as the chord structures, the timings, and of course the excitement and the feeling of power on the stage, plus the money.

You moved away from session work to be part of Deep Purple. Did you find the role of a session guitarist frustrating, and if so why?

I didn’t do an awful lot of session work because of the reading of music which was involved at the time. I did more of the rock sessions for Joe Meek, who wrote Telstar and various other things. It was funny sometimes to hear yourself on perhaps eight out of ten records being played on the radio, knowing that it was you playing the guitar. Session work was very good for cleaning up my technique and becoming familiar with studios, but it was sometimes very boring. I left because it was beginning to cramp my style.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Deep Purple were recognised as the loudest band in the world. Was that a proud moment for you?

I don’t think Purple became known to the public through sheer volume. That was just an easy target for the press to criticise, because the critics didn’t like the band. Purple played no louder than most of the other so-called big groups. In fact, some groups were most definitely louder than Purple. It depends also on the PA and who is operating it at the time.

Would you say your playing style is aggressive?

I would not describe my playing as aggressive, maybe more as destructive. No, maybe dramatic is my style. I’m just expressing my feelings at the time of playing, like any other musician. As far as having my own distinctive sound, that comes from not being very good at copying other guitarists. My style developed through sheer practice. When I was attending school I was constantly practising mentally, then I would rush home and practise until the early hours. I would practise about five hours a day. I was obsessed with playing. Then I joined various groups around the Hounslow area.

What was your motivation for quitting Purple – for the first time, at least – in 1974?

It was a case of the band being so much into the soul side of things. They were becoming cool, collected and very composed. Everything had to be just right. There were no chances being taken. The music was becoming very boring to me. That’s why I got out of it, because it was all too tidy and neat and nice. Stormbringer was a nice little album. And I don’t like making nice little albums. I don’t like to be predictable. I like to go from one extreme to another.

Did you tell your mother you were quitting Purple to form Rainbow?

I didn’t tell my mother. She always thought I was in the same band, which she didn’t know the name of anyway. In fact I think she still thought I was working at London airport. I was really excited making the first Rainbow album. There were none of these egos flying around. There was no one saying: “I’m not playing this, I’m not playing that.” It was just, let’s all play everything Ritchie says.

Why did you choose to perform a version of Purple’s Mistreated with Rainbow?

Mistreated is one of my favourites. It wasn’t typical of what Deep Purple did. I thought that it wasn’t a song that represented Deep Purple. It wasn’t a Deep Purple song, in my opinion. It was just a guitar riff I had in my head.

Geoff Barton is a British journalist who founded the heavy metal magazine Kerrang! and was an editor of Sounds music magazine. He specialised in covering rock music and helped popularise the new wave of British heavy metal (NWOBHM) after using the term for the first time (after editor Alan Lewis coined it) in the May 1979 issue of Sounds.