“The first transmission of semen by fax”: the story of Bruce Dickinson’s batsh*t crazy horror movie Chemical Wedding

God, w*nking and Aleister Crowley - how Bruce Dickinson made his critically slated horror movie Chemical Wedding

Iron Maiden singer Bruce Dickinson can turn his hand to pretty much anything. Not only does he front one of the world’s biggest metal bands, he’s also – deep breath – a fencer, an airline pilot, an author, a beer manufacturer and a sometimes radio DJ. But there’s one entry on his CV that doesn’t get talked about much: his foray into the world of film.

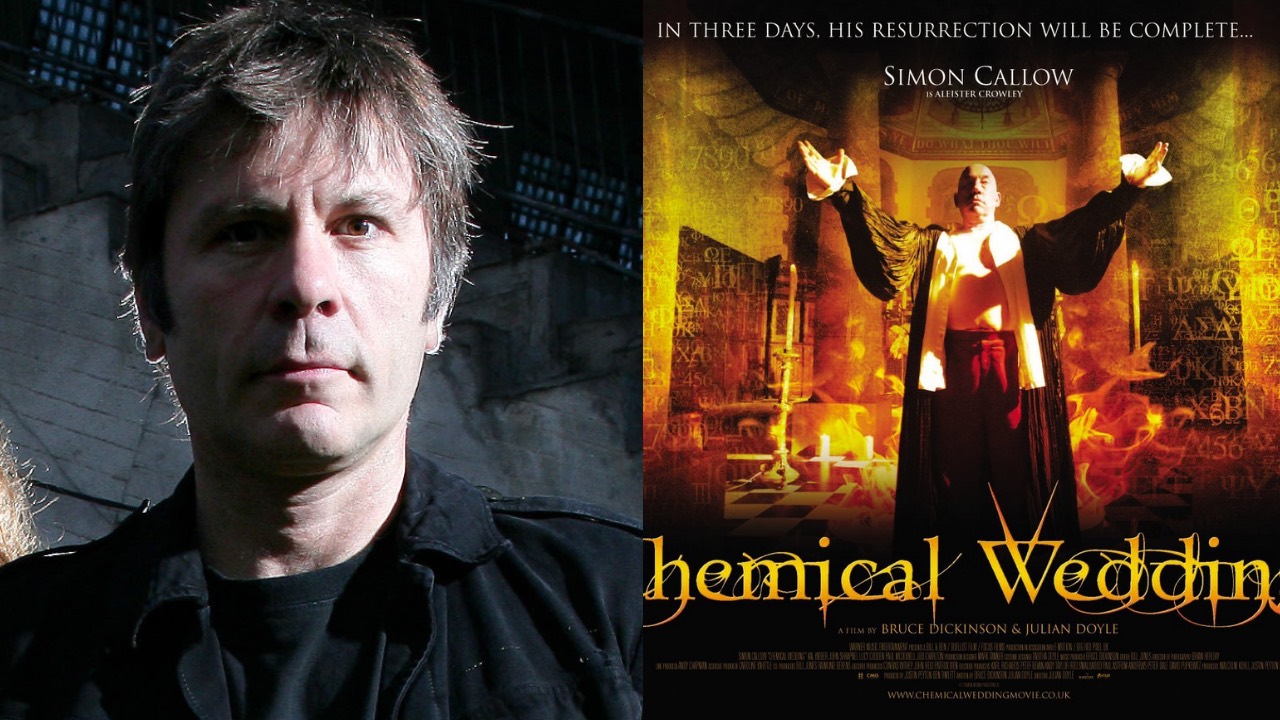

We’re talking specifically about Chemical Wedding, the low-budget horror movie that was conceived and co-written by Bruce. Inspired by the singer’s love of classic Hammer Horror films and their ilk, as well as his fascination with occultist Aleister Crowley, it wasn’t exactly short on talent: it starred sonorously-voiced thespian Simon Callow and was directed and co-written by Monty Python collaborator Julian Doyle. It even premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. So why don’t more people talk about it?

The simple answer is that it’s not very good. Callow plays Professor Oliver Haddo, who, after stepping into a virtual reality device that’s been secretly fiddled with by occultists, becomes the shaven-headed reincarnation of Aleister Crowley. As he marches around ranting about sex, God and the black arts and generally being a bit of a dickhead, it’s up to one of Haddo’s students and an American doctor to stop “the chemical wedding”: a ritual that will make him more powerful.

On paper, it was an homage to the British horror movies Bruce watched as a kid – The Devil Rides Out, The Wicker Man (recognise that title?), anything that came out of venerated studio Hammer Films. “They had Dracula, blood, fangs, sex and the devil,” Bruce said of those creaky but endearing old movies he grew up watching. “All this stuff was like, ‘Oh my God! That is so shocking!’, but it really kind of turned us on in secret. As kids, you’d be forbidden to watch it but, of course, it would be interesting, and you’d watch it.”

And Chemical Wedding did share some of their characteristics, not least an over-the-top approach that bordered on camp. Callow turns in a performance that raises the bar on the idea of overacting, while the sci-fi set of the virtual-reality lab looks like it’s been lifted straight from a Tom Baker-era Doctor Who serial.

And there’s the relentless desire to shock. Chemical Wedding has a plot, but it's mostly there so the film can hurry from graphic sexual taboo to graphic sexual taboo. You see it from the moment a reincarnated Crowley gets introduced. He marches to a lecture to the subversive soundtrack of Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus. Then, he proceeds to parody the “To be or not to be” soliloquy from Hamlet, changing it to “To pee or not to pee” and uttering the word “cum” innumerable times before pissing on his students. It’s supposed to be shocking, but it’s just childish.

The rest of the film is no less highbrow – a slideshow of orgies, threesomes and and middle-aged men wanking into fax machines while getting flogged. “This is the first transmission of semen by fax,” Bruce promised one interviewer ahead of the film’s release.

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The singer actually started writing the movie in the mid-90s, after his exit from Iron Maiden in the wake of the Fear Of The Dark album and tour. He teamed up with Doyle – who directed the video for Iron Maiden’s 1988 single Can I Play With Madness – to work on the script, originally under the working title The Number Of The Beast.

“We changed that because a friend of Julian’s had written a novel called The Chemical Wedding,” he continued. “He said, ‘I think this’ll be a great title for the movie. It’s not as obvious as The Number Of The Beast, but the ‘chemical’ part refers to alchemy: an alchemical wedding.’”

It would take well over a decade before the idea came to fruition, by which time Dickinson had released a solo album in 1998 titled The Chemical Wedding (confusingly based on the works of visionary 18th century poet William Blake rather than Aleister Crowley) and rejoined Iron Maiden the following year.

The movie was eventually released in 2008 (it was titled Crowley in the US). Dickinson’s involvement gave it a bigger profile than it would otherwise have had (as well as his co-writing credit, he also has cameo roles as a ‘Blind Man’ and ‘Landlord’ according IMDB.com credits, though they’re seemingly so fleeting as to be invisible). It didn’t shy away from leaning on Bruce’s day job either – Maiden’s Can I Play With Madness and The Wicker Man both appeared on the soundtrack, while Dickinson’s own 1998 track Chemical Wedding was, unsurprisingly, the title song.

None of that impressed the reviewers. The reception that greeted Chemical Wedding could charitably be described as “lukewarm”. “It just feels like it was shot from an unpolished first draft,“ wrote Den Of Geek. The Guardian was slightly kinder: “It’s unintentionally funny and indifferently acted…But it’s never boring.”

Fans were equally unimpressed – despite its Cannes premiere, Chemical Wedding came and went without much noise. Part of this could be down to the fact that ‘torture porn’ was the biggest trend in horror movies at the time, with a new Saw movie seemingly arriving every year. But it’s mainly because the film is a bit of a stinker. Even today, its audience score on Rotten Tomatoes sits at a lowly 30 per cent.

The movie’s biggest cheerleader at the time was Bruce Dickinson himself. “In brief: it’s funny, it’s gross – think Withnail & I meets The Wicker Man. It's The Da Vinci Code, but good,” he enthused, though many who watched it would dispute ‘funny’ and ‘good’. But even the normally loquacious been strangely silent about it ever since – and there’s certainly never been any talk of a sequel. All things considered, it’s probably for the best.

Louder’s resident Gojira obsessive was still at uni when he joined the team in 2017. Since then, Matt’s become a regular in Metal Hammer and Prog, at his happiest when interviewing the most forward-thinking artists heavy music can muster. He’s got bylines in The Guardian, The Telegraph, The Independent, NME and many others, too. When he’s not writing, you’ll probably find him skydiving, scuba diving or coasteering.