The Doors: Krieger and Densmore on America's most influential band

With new DVD Feast Of Friends on the horizon, in a CR exclusive we bring together the two surviving members of The Doors – for the first time in a decade.

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

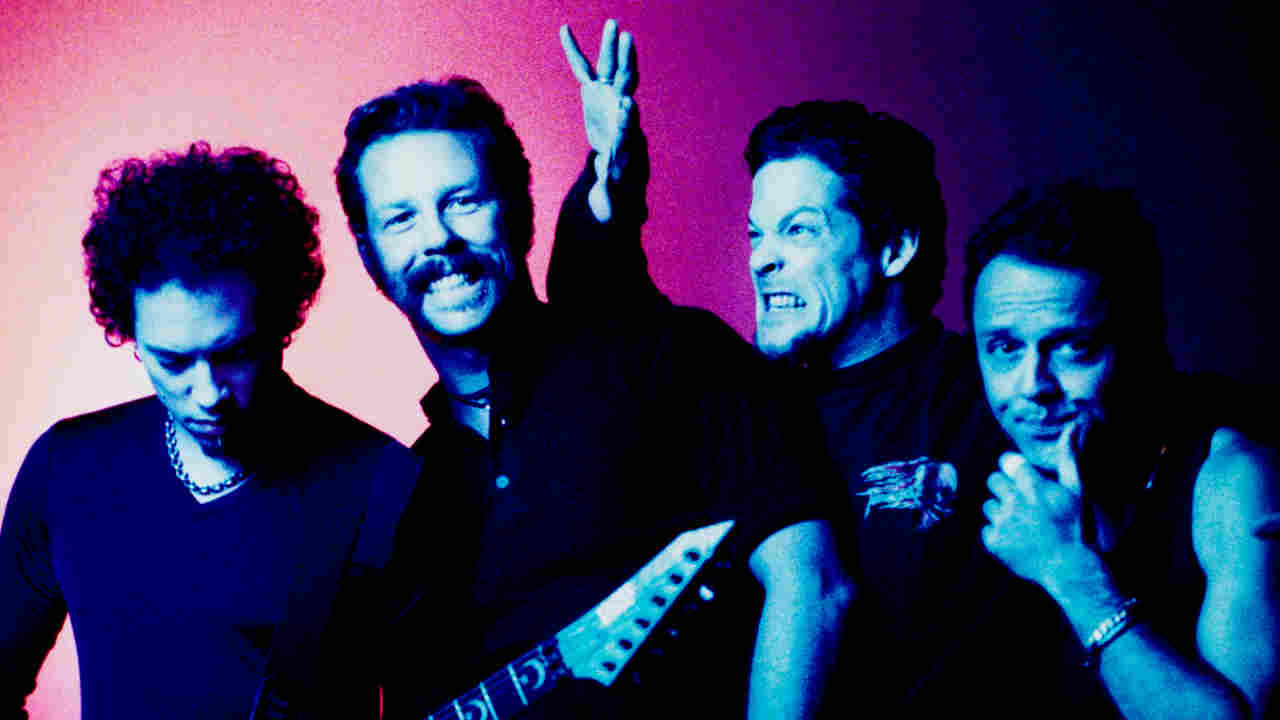

The two surviving members of The Doors sit at either end of a leather couch, as far away from each other as possible, a palpable sense of unease separating them. “This doesn’t happen very often, so you must have some pull somewhere,” guitarist Robby Krieger says wryly. Krieger and his former bandmate, drummer John Densmore, have come together in the LA offices of the company that manages The Doors’ estate. They’re surrounded by mementos of their success, which began further along the Sunset Strip at the fabled Whisky A Go Go club back in 1966.

Whose idea was it to finally release Feast Of Friends?

Robby: I don’t know. Maybe the fans. We interact a lot online with the fans, and I think they really wanted to see it – the whole thing, rather than just pieces stuck into other films.

Why now?

Robby: Maybe we need the money now.

John: As the late, great Ray Manzarek would say, it’s an alignment of the stars. It’s a cosmic conjunction of planets that made this moment happen.

Was the release of Feast Of Friends in any way prompted by the passing of Ray?

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Robby: No, nothing like that.

Did you initially have any reservations about making the film?

Robby: I thought it was kind of a waste of money, actually.

How do you feel now?

Robby: I wish we’d done it more now. I wish we had done all of our tours like that, with a film crew.

Was it painful or joyful watching the footage this time around?

Robby: It was fun because I hadn’t seen it for a long time all together like that. It was very enjoyable.

John: To me it was poignant. Two Doors are gone, and seeing Jim and Ray on the sailboat at the end, it’s very touching. It has the beautiful adagio for strings, and you’re seeing this beautiful sailboat, and Jim, and Ray. It’s powerful.

Will it shed a new light on The Doors?

Robby: I think so. I even said to myself: “Man, when people see this who have already seen [Oliver Stone’s 1991] The Doors movie, and they think that’s how Jim was, that he was a total idiot, and now they’ll see him as a real person… how brilliant he is, a real person.” Talking to the priest and stuff like that. I know that always bothered Ray a lot, the fact the movie… As good as The Doors movie was – I thought it was a great rock’n’roll movie – the script was just so stupid.

John: Wait a minute. It’s really good but it’s stupid? Which is it?

Robby: As a rock’n’roll movie, it’s good. I think it’s one of the best rock’n’roll movies out there.

John: Oliver chose to do the tortured artist, and he showed a lot of the torture.

Robby: He showed a lot of the drunk, none of the guy who was a real person.

John: The only thing that bothered me is it didn’t have enough of the sixties for me.

Robby: It didn’t have enough of the guitar player for me.

The two of you were involved in a long and bitter legal battle. What brought about the reconciliation?

John: Time. Passing of Ray.

Robby: All of the above. We still hate each other.

John: There was a screening of another documentary, Mr Mojo Risin’: The Story Of LA Woman at the [Los Angeles] County Museum. They wanted a Q&A, and we did our blah, blah, and it was really cool that we played music for ten minutes – just the guitar and hand drums. We hadn’t played these songs in a long time. It was sweet, man. For me, in four bars I was back. It was the old days.

Did you remain in contact in the years of the dispute?

John: Not too much.

Robby: Just in court [laughs].

Is there a sadness that you didn’t reconcile when Ray was around?

John: I was very thankful that he picked up the phone when I called him after I heard he was really getting sick. We didn’t talk about any of the struggles, we just talked about his health problems. But it was healing, that’s for sure.

Next year marks The Doors’ fiftieth anniversary. How do you feel about the band’s legacy?

John: It’s all about the drumming, really. Not the guitar playing. Think about it. If you’ve got a band with a shitty drummer, you’re fucked; if you’ve got a band with a shitty guitar player, you can skate by [laughs and effects a rim shot]. That was a joke.

Robby: No. It’s just another number. Fifty-one is just as good.

Are you happy to have the band’s legacy intact, or would you have preferred to have carried on and become something like the Rolling Stones?

Robby: Obviously we wish that Jim and Ray were still here and we could still play if we wanted to. The fact is we didn’t have a choice. A lot of bands play too long. But you just never know. Unless it would have happened you can’t say whether it would be good or bad.

John: Yes and no. Jim’s twenty-seven forever. Everyone always says: “Well, if Jim was around today would he be in AA, clean and sober, dude?” I always said: “Nah. He was a kamikaze drunk.”

John, in your book Riders On The Storm you wrote: “I had no idea it was going to be that dark of a band.” Were you surprised by the direction the band took?

John: Jim’s self-destruction was hard. It wasn’t fun. I knew we were making magic, and there was a crazy guy in the band. No one could stop him. Not every artist is self-destructive and creative. In his case it came in the same package, so it wasn’t easy.

Do you consider The Doors a dark band?

Robby: In some ways, but not always. Jim could be really funny sometimes. Probably the dark outweighed the light. I don’t think that was on purpose, that’s just the way it came out.

Robby, you said that the first day you got together you thought you were as good as the Rolling Stones.

Robby: It just felt like: “This works, man. This is a band that could go all the way.” I had been in different band situations before that – not very many – but this was just a cut above everything.

The original band were only together for a little over five years, yet you’ve found yourselves spending the next forty-five years talking about them. Has it been frustrating to reflect on it rather than live it?

Robby: Yes. It would have been better to live it.

John: It’s been downhill ever since you wrote that fucking Light My Fire.

Is it hard to have your lives defined by something you did so long ago?

Robby: It’s a good problem to have.

Are you both at peace with the idea of being known as John Densmore of The Doors and Robby Krieger of The Doors? Is that something you wrestled with?

Robby: I fought against it for a while. I had all my solo albums, and I never wanted to play Doors songs for a long time. Then I’d start seeing all these Doors tribute bands. Then one day I went and sat in with Wild Child and they were having so much fun. I’m going: “How come they get to have all the fun?” So I started doing more Doors stuff in my band.

Is that the same for you, John?

John: I’m coming back around, yeah. In Riders On The Storm I wrote that ‘of The Doors’ is permanently etched on my forehead. And I’ve come to terms with that. I remember Ray saying to both of us: “It’s better to have been in The Doors than not.”

What is your happiest memory of The Doors?

John: The early days, when we’re making the transition from the Whisky to small concert halls and I’m sensing: “Goddamn, we are going to make a living at this. The train’s leaving the station. It’s going to happen.” The mass adulation of Madison Square Garden is great, but sensing that we’re going to have a career playing music… Fuck, man, that’s the ultimate.

Robby: Maybe hearing Light My Fire go to number one on the radio. We were just sitting around the table listening to the Top Ten countdown, and when Stevie Wonder came up at number two we knew we were number one. That was pretty cool.

Do you have any regrets?

Robby: We could have tried harder to keep Jim from killing himself. But in those days that wasn’t cool. You didn’t intervene with somebody’s drug problem.

John: We tried. We tried to have a meeting, and he didn’t show up.

Robby: He did, remember? He came to my dad’s house that day and we talked, and he quit drinking for about a week. We did a couple of things like that. He definitely knew that we weren’t cool with it. But he couldn’t control himself, basically. He was on a runaway train, and the only way to get off is jump off, and you’re going too fast. That’s how I always thought of it. My dad tried to convince him to go and see a shrink.

John: He went for one session and put the guy on the whole time [laughs].

Robby: The problem was he was probably smarter than any psychiatrist.

After Jim’s death you carried on, recording two more albums. How tough a decision was it to keep going?

Robby: It was very tough.

John: It wasn’t tough at all.

Robby: I mean, you knew it was not going to be easy because our front guy had gone, but what else could we do? We didn’t want to replace Jim, because how could you do that? And to just go on ourselves without any frontman was not something we wanted to do. But we liked playing together.

John: That’s what I was going to say. It wasn’t tough. We didn’t want to give up what the trio had musically developed together. We just read each other’s lives, musically.

At one point, John, you said: “The Doors without Jim is like the Stones without Mick. That’s ludicrous.” Yet the three of you decided to carry on together without Jim. How were you able to reconcile that?

John: We had a very lucrative deal for five albums after Jim died, and we only did two, so I think we realised we’re missing the guy in the leather. Without Jim it was falling apart. He was the glue.

Robby: Well, we actually went to England. We all moved over to England after the second album, to try and find a singer.

John: Don’t tell the truth.

Robby: We were all over in England, and it was kind of stressful because of the horrible place we’re living in. They’d turn the electricity off at night. Then John and I said: “We think the band should go in a hard rock direction.” Ray wanted to go more jazz, so that was it for him.

Was it difficult to adapt to life after The Doors?

Robby: When you’re in The Doors, life is not very realistic – limos and all that stuff. So when it was over, you say: “What am I going to do the rest of the time?” It becomes a problem. Not musically. I had various bands that I was doing, and we knew that none of them would ever be as big as The Doors, but you can’t stop playing music.

John: [To Robby] Do you get recognised much, like when you’re just at the market or something?

Robby: I average once a day.

John: It’s sort of increased because of the web and all that shit.

Robby: Before, it wasn’t so much because you’d gotten older and people don’t recognise you.

John: They know what we look like now. I’m not crazy about it interfering with my private life.

Robby: You have to blend in more, John. See, you gotta stop wearing those shoes. [Densmore is wearing black Vans customised with neon piping.]

_Is it a nice experience to be recognised? _

Robby: Sometimes it is, sometimes it isn’t. Like the one guy that came up to me. I was at a stop sign, and he came running up to the car and said: “Hey, you Robby Krieger?” “Yes.” “You and I have to take acid and die together!”

John: When my kid’s in school he gets: “Is your dad…?” And I said: “If you’re hassled a lot about it, just say: “No, he’s not my dad!” And they’ll go: “Okay,” and walk away.

John, it’s fair to say you had an uneasy relationship with Jim. How would you describe it?

John: Love-hate. I loved him for his creativity, hated him for his self-destruction. But, as Robby says, in retrospect, with time, he couldn’t help it. It’s more love now.

_He had a profound impact on you too, Robby. In one article you stated: “Dealing with Jim kind of changed me, too.” How did it change you? _

Robby: It would change anybody. He was the most influential person in my life, except for my parents. That’s how he was. I think people sensed that, even in the audience.

John, you talked of being intimidated by Jim. What was intimidating about him?

John: He was really well read, and I wasn’t. Musically he didn’t know what I knew, but I didn’t know what he knew as far as reading and literature. Now I am slightly caught up. I keep getting blown away by his poetry and lyrics.

Do you think he was trying to be intimidating?

John: No!

Robby: Oh yeah!

John: No. Yeah! He would manipulate people.

Robby: He would take acid, and he would always find the guy who was taking it for the first time and he’d try and freak the guy out; he’d turn the lights on and off real fast or something like that. He liked to be in control. He liked manipulating buttons.

John: He liked pushing boundaries. Testing people.

Jim would frequently quote the William Blake line: ‘The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom’. Was he was trying to live by these words?

Robby: Yeah, he did try to. One time when he contracted syphilis, and he heard that if you get syphilis you go crazy, he said: “I’m not going to go to the doctor. I’m going to see if I really get crazy [laughs]” He lasted about a week before he went to the doctor.

When Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin died, given Jim’s excesses did you think perhaps he would be next?

Robby: Yes, especially when he said that.

John: He intimated that you’re drinking with number three.

_Robby, you once said: “It would have been so great if we’d just had a guy like Sting, a normal guy who’s extremely talented too. Someone who didn’t have to be on the verge of life and death every second of his life.” _

Robby: I did say that. It would have been. Not Sting himself, maybe. But, hey, it would have been great if Jim hadn’t had the demons and could still write that stuff. Maybe that’s impossible, I don’t know.

John: In his case, no. The weight of the demons was on us too.

_In your book, John, you wrote: “This isn’t the way it’s supposed to be. It’s supposed to be relaxed and fun being in a famous rock’n’roll band.” It appears that you weren’t able to enjoy your success. _

John: It was just, phew, man! I used to go to the Whisky and hear Love, and I’d think: “I’m fucking better than that drummer. Why am I not in that band? Why am in this band with this crazy guy?” I don’t feel that way at all now. I also thought I could have played in The Byrds easy, with one hand. But apparently this band has gravitas, and I’m proud to have been a part of it.

John, during the recording of the Waiting For The Sun album, you were getting headaches and stress-related rashes.

John: I had a fucking rash for a couple of years. No stress [laughs]. That’s the weight of the demons, the elephant in the room, and nobody’s acknowledging it. I think they say that in AA. There’s elephant shit everywhere, but that’s our meal ticket. Keep it quiet. I was sick, but I was psychologically sick too. Like: “What’s going to happen to Jim? Oh fuck!”

Robby, your relationship with Jim seemed rather less strained. Why do you think that was?

Robby: I don’t know. It just didn’t bother me as much as it did John, maybe. To me, it was: “Okay, this is how it’s supposed to be in a rock’n’roll band.”

When did things start to change with Jim?

Robby: As soon as we got big. Billy James, who was the guy that signed us to Columbia Records, told us: “If that guy ever gets power, look out!” [Laughs] That’s when Jim got power, when the Whisky started happening, and people started sucking up to him. There was no filter.

_What was life like on the road with The Doors? _

Robby: It was usually a constant worry about where Jim was. I don’t know why we worried, he always showed up for the gig. He’d just take off with anybody and take whatever drugs they had. There was a time in Amsterdam, somebody gave him a block of hashish and he just swallowed it and ended up in the hospital. That was the gig he missed.

Did you feel that the New Haven incident, in which the policeman sprayed Mace at Morrison backstage prior to the show, marked the beginning of the end?

John: I didn’t know it was the beginning of the end, but it was pretty scary. The cop pushed his buttons and he pushed them back.

Were you fearful that it might all suddenly just end?

Robby: I wasn’t. I thought: “This is pretty cool, man, the cops up on stage.”

John: Dragging him off stage and kicking the shit out of him, that was cool?

Robby: Well, I didn’t know they were going to beat the shit out of him. The audience never forgot it. It made the movie.

At one point you wanted to stop doing live shows. Why was that?

John: Jim’s alcoholism. There wasn’t any control when we played live. What was so tragic for me was we were really good live and I didn’t want to see that eroded. If he was loaded in the studio we could go home. There weren’t ten thousand people watching.

John, you were the last member of The Doors to speak with Jim, when he called you from Paris and talked about coming back to work with the band again. Given your strained relationship, were you happy for him to remain in Paris?

John: Like I said, I loved him for his creativity and I miss those words and melodies. I was also extremely worried about his health. He sounded kind of fucked up on the phone. I was trying to see if he was loaded. A little bit.

But you would have welcomed him coming back?

John: If he had cleaned up. I love the French, but unfortunately they drink wine for breakfast.

The band’s fortunes were waning somewhat at the time of Jim’s death. Did you feel that things were beginning to fall apart?

Robby: Pretty much, yeah. That wasn’t the best time. We couldn’t really play anywhere because there was a thing called the Hall Owners Association and they had banned us pretty much from playing any of the good places.

What was your initial reaction when you got the news of Jim’s death?

Robby: I didn’t believe it at first. There were always rumours of Jim’s death. So we didn’t really believe it. We sent our manager, Bill Siddons, over to Paris to see what had happened. Then he came back and said it was all true. “Well, did you see the body?” “No.” They buried him, like, the day after. No autopsy, no nothing. We had no doubt that he had died, though.

Was there ever a sense of guilt?

John: I don’t feel guilty now, because I just did what I could then. But I’m not the same person I was then. You know this question: “Would you do it differently?” It’s like: “Yes. Hopefully I would learn from what I went through.” And: “No, because I’m proud of what we’ve done.” So yes and no to that.

Has there been a point when you’ve felt guilty, Robby?

Robby: No, not really. Because in a way Jim got what he wanted. He really was interested in death. Not that he wanted to die, but he was so curious about it. I think he really didn’t plan to live very long. I really didn’t feel bad for him. Not at all. He was not a happy camper, especially in the last days. The whole trial thing going on and all that. Everybody says: “Well, he got fat on purpose and he was trying to stop being a rock star.” I don’t think that’s true. I think he just got fat. I don’t think he liked it that much. I think he was fat and unhappy.

Why did you decide to re-form The Doors in 2002?

John: Oh fuck. That’s a whole can of worms. I have another three-hundred-page diatribe on that.

Robby: Like I said, I had been doing more Doors songs in my band, and I called Ray one day and said: “Hey, we haven’t played this stuff for thirty years. Want to try it again?” Actually, we got together to do this VH1 Storytellers [in 2000], and we had different singers, and John played on that. That went very well so we decided this might work.

John: First I said: “Robby, why don’t we don’t go on tour with a bunch of singers so we don’t fall into the trap of one guy.” Which you said was a great idea, but too expensive. True. Then I got this ringing in my ears around that time – tinnitus. I couldn’t go.

Now, as you reflect back over nearly fifty years as a member of The Doors, with all the highs and lows that it’s entailed, was it all worth it?

John: Worth the struggle? Yes. Apparently. People seemed to like what we did. And Robby got a bunch of money, which is what he’s interested in.

Robby: Yes. Never a doubt.

LIGHT MY IRE

In 1966 everyone loved The Doors. Everyone except East Coast rivals The Velvet Underground.

Doors fans may have been grief-stricken at the news of Jim Morrison’s death, but his detractors weren’t. Chief among them was Lou Reed, who said: “Somebody got a phone call saying Jim Morrison had died in Paris in a bathtub. And I said: ‘How fabulous, in a bathtub in Paris!’ I had no pity at all for that silly Los Angeles person.”

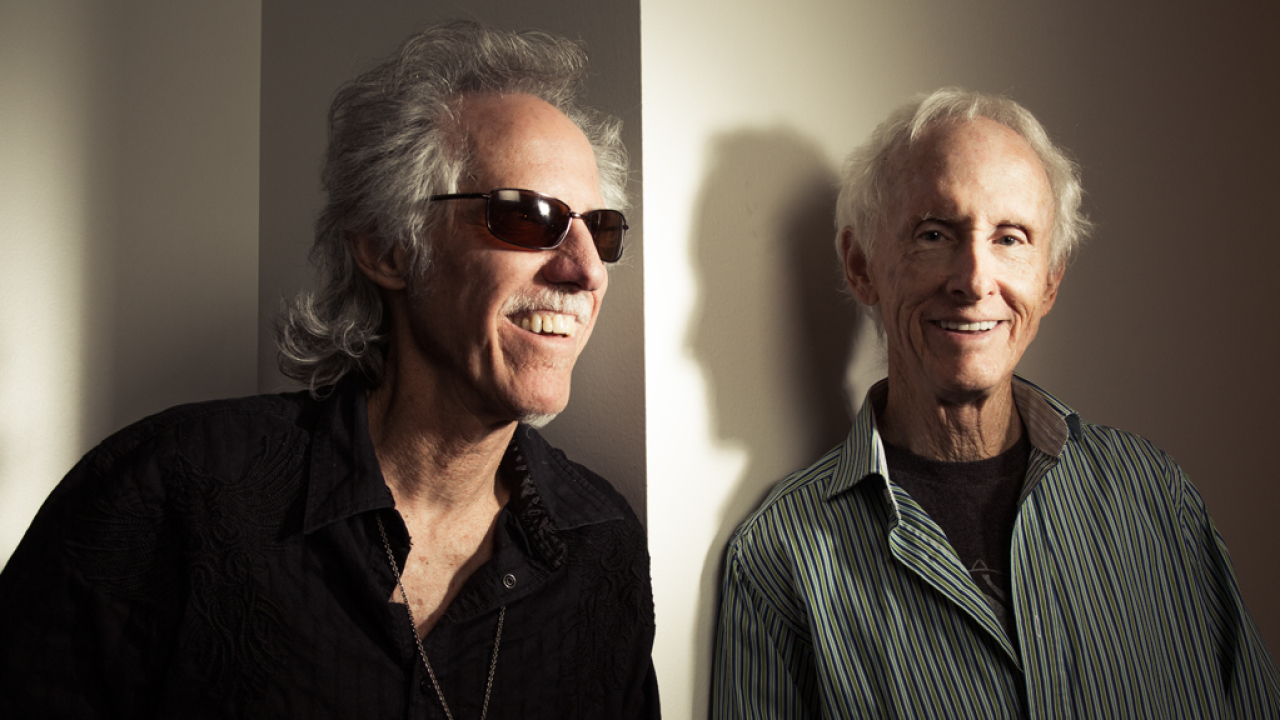

Ever since his early Velvet Underground (pictured above) days, Reed’s attitude to The Doors had been one of antipathy, symptomatic of his mistrust of the West Coast scene in general. Reed’s basic argument was that the VU were “really, really smart” and the California bands were “really, really stupid. It was purely a matter of brains.”

This animosity was most likely aggravated by the VU’s West Coast debut at The Trip, LA’s hip nightspot, in May 1966, where the Velvets were jeered. John Phillips, Mama Cass, Sonny and Cher, Ryan O’Neal and The Byrds were among those in attendance. Cher left early and was quoted in the next day’s paper as saying the VU’s music “will replace nothing, except maybe suicide”. Reviews were similarly unkind.

Also in the audience for that opening night was Jim Morrison, just starting out with The Doors. The Velvets were then part of Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable, a multimedia show that featured dancer Gerard Malanga. The latter’s performance saw him cavorting around in leather with a whip. Six months later The Doors went to New York and played at Ondine’s. Morrison had co-opted Malanga’s whole leather schtick. As Warhol recalled later: “[Gerard] flipped. ‘He stole my look!’ he screamed, outraged.” Today Malanga is a little more diplomatic. “Let’s say he appropriated it out of inspiration,” he says.

Warhol had been quick to spot the screen potential of Morrison. During The Doors’ East Coast visit, he invited the singer to take a lead role in a porn movie, I, A Man. According to the filmmaker, Morrison “agreed to bring a girl over and fuck her in front of the camera. But when the time came he never showed up.”

Rob Hughes

Kevin Murphy is a writer, journalist and presenter who's written for the Daily Telegraph, Independent On Sunday, Sounds, Record Mirror, Kerrang!, Metal Hammer, Noise, Select and Event. He's also written about film for Empire, Total Film and Directors Guild of America Magazine.