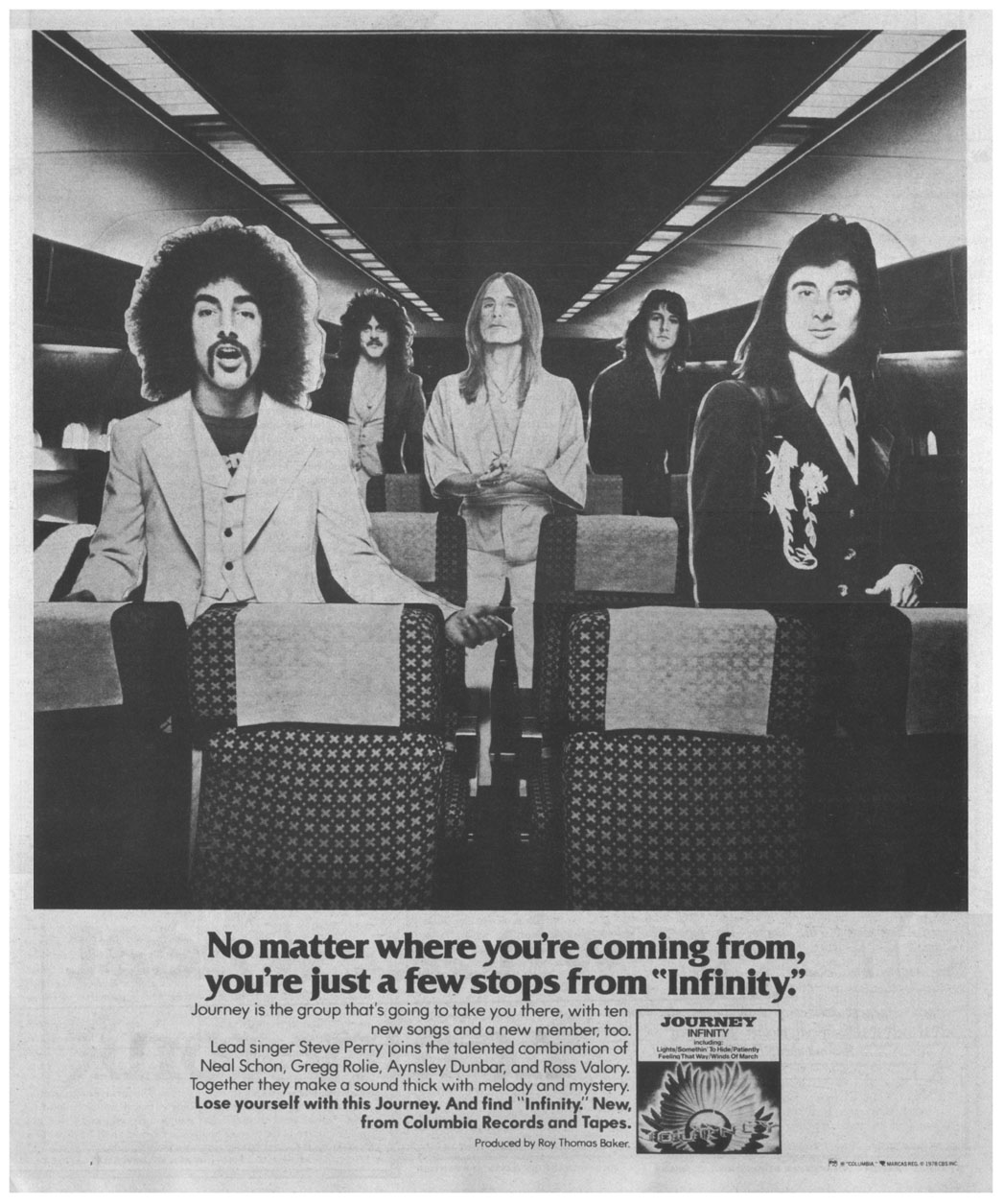

Start believin': The story of Journey's Infinity album

By 1978, Journey had a loyal muso following but were still looking for their breakthrough. What they needed was a singer would could turn their improvisations into anthems. Cue one Steve Perry...

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

“If I had the chance I would do it all again exactly the same way,” says Steve Perry. “I swear to God. I would not hesitate for a minute.”

Steve Perry is on the phone. The commonly held notion that he’s a dark and sombre recluse couldn’t be further from reality. He’s a veritable ball of energy, dispensing charm and cheer like it was going out of fashion. Before long he’s singing down the phone, and hinting that he wants to stop kicking his heels and put a ‘section’ together (that’s old-school parlance for a band).

We’re hooked up to talk about Journey’s fourth album, 1978’s Infinity. Steve doesn’t give many interviews, but he speaks at length and opens his heart about a record that changed his life, and the course of history for his band;

a record that heralded the arrival of one of the greatest voices of our time, and set Journey on a crash course for superstardom that would ultimately result in their 1981 anthem Don’t Stop Believin’ becoming, in 2009, the best-selling song from the 20th century on iTunes (currently seven million downloads and counting).

All the facts and figures in the Journey story complete a cluster of astonishing accomplishments which are the envy of the music industry. Achievements that, in today’s music marketplace, would be almost impossible to duplicate. For a good 12 years, Journey took position at the very top of the food chain, releasing album after album of instantly recognisable songs all embellished with clear-cut hooks and melodies to die for.

These are records that have stood the test of time, and because of the musicianship inherent in each and every song they have never sounded dated. In many ways, then, Journey were not only pioneers of a style but they were also uniquely aloof – in a league of their own and a world away from the processed, hard-on-the-ears clamour of similar-sounding acts trying to carve out a slice of the same market.

When all is said and done, it was Steve Perry’s presence that really cemented the band’s reputation. Prior to his arrival Journey had been a fairly inconspicuous and mainly instrumental fusion outfit, looking to muscle in on the jazz-rock scene perpetrated by the likes of Weather Report and the Mahavisnu Orchestra.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Great players, Journey’s early style and meticulous arrangements would, inevitably, limit their appeal unless radical changes were implemented. Their sound had attracted stellar critical reviews but, as a commercial entity, they were stuck in a rut. Not surprisingly, at the behest of their label, Columbia, changes needed to be made, a radical remodelling of the band was demanded to expand their appeal.

Infinity marked Perry’s initiation into the world of professional recording, a milestone in contemporary aural acrobatics. Within the confinement of 10 songs he effortlessly switched from breezy improvisation (La Do Da) to epic bombast (Wheel In The Sky), providing a template from which future creative diamonds would emerge, forever cementing the appeal of Journey and securing his place in rock’s vocal Hall Of Fame.

- Steve Perry on Infinity, track by track

- Journey’s Cain says it’s time for band to put Neal Schon spat behind them

- Def Leppard and Journey announce massive 58-date North American tour

Unlike the brusque delivery of British blues-belters such as Coverdale and Rodgers, Perry’s reference points evolved from diverse and somewhat unexpected sources, including the sweet soul sounds of Sam Cooke and Smokey Robinson.

Born in California in 1949, Steven Ray Perry was of Portuguese extraction. The family’s original name of Perrera was quickly anglicised to Perry when the family had entered the US, to disguise the fact that they were European immigrants (a common policy back then to improve employment opportunities). Growing up, his epiphany moment was hearing the Sam Cooke song Cupid on the radio while riding in his mother’s car. From that moment on, becoming a musician was all he dreamed of.

By his teens, Perry was a veteran of several garage bands, singing and drumming with names such as The Nocturnes, Dollar Bills, Ice (also featuring future producer Scott Matthews) and The Sullies. He even joined a Toronto-based unit called Privilege and toured Canada.

“They were a 12-piece brass group that had played in my home town near Fresno,” says Perry. “I was so blown away by how amazing they were I kept in touch with the guitar player, one of two brothers, Andy and Harry Krawchuk, and they hired me for a few months. I toured Canada with them – they were a very high-end covers band.”

By the mid 70s, Perry focused all his energies upon infiltrating the music business and moved to Los Angeles, where he formed a band called Pieces alongside experienced musicians like Cactus/Beck Bogert & Appice bassist Tim Bogert, guitarist Tim Denver Cross and drummer Eddie Tuduri. Sadly no deal was forthcoming. Bogert and Tuduri then moved to the UK to join British prog rockers Boxer.

In order to support himself, Steve took a gig as a second engineer at Crystal Studios while piecing together his next outfit, called Alien Project (the group occasionally switched to the moniker of Street Talk, which Steve later used for the title of first solo album). It was this unit that caught the ear of a couple of labels, including Chrysalis and Columbia. The latter’s A&R man, Michael Dilbeck, was hot to sign them.

The group featured drummer Craig Krampf who would later go on to become an in-demand session musician.

“Craig had some contacts in the business,” says Steve, “enough where he could pick up the telephone and call them. He was really good at hustling and got us into Chrysalis and Columbia. Michael Dilbeck was one of the Columbia people who heard Alien Project and liked it. He talked with Don Ellis who was running the West Coast office. They were thinking of signing the band.

“Back in those days, the sweetest thing that could happen was signing to a record label and making a record – that was the pathway of dreams for all of us. Michael liked the band, but I must say the demo got kind of shelved a little bit, meaning he liked it but wasn’t really moved to sign us right away. So we were kind of vacillating, thinking should we go back to Chrysalis who had been pretty excited. Then the next thing that happened was, someone at Columbia decided to go around Michael and send my demo tape to Herbie Herbert, Journey’s manager, in San Francisco.”

It’s impossible to talk about Journey without the towering presence of their manager Herbie Herbert, a bear of a man with a personality and reputation that, at times, has almost seemed to eclipse (pun intended) the band. Think Peter Grant, if he weren’t quite so intimidating and wasn’t surrounded by henchmen with fists at the ready. Herbie loved music and loved Journey. He dedicated his life to their needs and to the advancement of their career. He had a vision and nobody was gonna fuck with it, and recruiting a vocalist to the group was paramount to his plan.

In Steve Perry, Herbert had found the proverbial needle in the haystack – a vocalist with unlimited range, unique delivery and looks that killed. The consummate frontman, in fact. There is every reason to believe that Perry singlehandedly rescued Journey from interminable underachievement.

“This is where its gets complex,” Steve says, of his initial meeting with Herbert. “Herbie had already heard my name. I was mentioned to him by one of his team, Jackie Villanueva. Jackie had a friend in Frisco by the name of Larry Luciano who, as it happens, was a childhood friend of mine. We had grown up together. Larry had moved up there and become friends with Jackie and the Santana clan. That’s when he and Larry became friends with Herbie.

“Larry told him that he had a cousin called Steve Perry and that I was a pretty good singer and he should check me out. That never came to fruition until the guy at Columbia sent the Alien Project demo tape to Herbie, who saw the name and thought, ‘Steve Perry… Hmmm… Larry’s cousin?’ And of course it was. Then Herbie called me up and said, ‘I love the way you sing, I love what you’re doing and I love the band.’”

However, this budding relationship between Herbert and Perry was suddenly derailed due to the tragic death of Alien Project’s bassist Richard Micheals Haddad, who was killed in an automobile accident on the July 4th weekend. The rest of the band felt like the rug had been pulled from under their feet.

“We were due to resume talks with the labels after that weekend but, of course, it never happened,” says Perry. “I started to pack it in and called my mom to say, ‘I’m coming back home.’ It felt like the closer I got to achieving my dream, the bigger something in my life would say ‘no’. At that point I’d never been so close to someone who had died and I thought, ‘I’m not supposed to do this.’

"I was so distraught and knocked back by it all. But my mother said, no, don’t give up – something will happen. And that’s when I got a telephone call from Don Ellis, who said, ‘I’m sorry to hear about your bass player, but Herbie Herbert has your tape and he loved it. We have Journey on Columbia and we’d love you to be the singer of that band. What do you think about it?’

“I had seen Journey come to town and play many times in LA and I knew that my voice with Neal Schon’s guitar would be like salt and pepper.

"I knew that if I could ever work with him that would be a dream. It was Neal who really attracted me to that set up.”

Journey’s origins go right back to the beginning of the 70s, with the band members based in San Francisco, the centre of hippy counterculture. Keyboard player Gregg Rolie was a founding member of Santana, immortalised by the group’s stunning appearance at the Woodstock festival. The footage of Rolie trashing the living daylights out of his organ during Soul Sacrifice became iconic.

Guitar prodigy Neal Schon was also cooking up a name for himself in the Bay Area, not only as another alumni of Santana but also by working his way through a number of musical cabals, including Latin rockers Azteca and the Golden Gate Rhythm Section. Joining Journey on bass was Ross Valory and second guitarist George Tickner, both of whom were from the curiously named Frumious Bandersnatch. The band’s first drummer was Prairie Prince from fellow SF band The Tubes, but he was quickly replaced by British ex-pat Aynsley Dunbar, who had moved to the US to play with Frank Zappa’s Mothers Of Invention.

Journey’s interest in experimental jazz-fusion was confirmed on their self-titled debut album issued in 1975. A classy work, the album resonates with a surety beyond their recent formation, all players coming across as both fluid and experienced. Neal Schon in particular rips up his fretboard like combination of Jeff Beck and Robert Fripp. Check out the seven-minute long Kahoutek where he trades call-and-response licks with Gregg Rolie.

Surprisingly for such complex music, the album sold moderately well, reaching No.138 on the Billboard chart. After George Tickner bailed out of the band, their next two albums – 1976’s Look Into The Future and 1977’s Next – repeated the pattern, with Gregg Rolie making a concerted effort to deliver reasonably effective vocals atop what was clearly a jazz-fusion fanfaronade.

Despite the concerted efforts of both Columbia Records and Herbie Herbert, it was clear that Journey had reached a sales ceiling. They could continue no further in an upward trajectory unless major changes were implemented. Effectively this meant adding a proper vocalist/frontman and modifying the musical direction. It was a bitter pill to swallow but the band took it on the chin and cast their net to see what was possible.

They settled on Californian Robert Fleischman, who teamed up with the band in June 1977, at the request of label president Bruce Lundvall, who asked Robert to fly to San Francisco and see the band. Fleischman rapidly assimilated with his new bandmates, co-writing a handful of songs, three of which – Wheel In The Sky, Anytime and Winds Of March – would later surface on Infinity. Pretty much an unknown, Fleischman was, at one point, in the running to replace Peter Gabriel in Genesis for their A Trick Of The Tail album, a move scuppered when Phil Collins made a last-minute decision to step up to the microphone.

Things were moving swiftly – if not completely smoothly – when, as previously mentioned, Steve Perry’s name entered the frame. Fleischman had been out on the road with Journey during the summer, supporting Emerson, Lake & Palmer, and matters had progressed to the point where it was understood by all that Robert was their new vocalist. Behind the scenes, however, Robert had apparently been ruffling feathers. Herbie was seemingly concerned that Fleischman was unwilling to relinquish his previous manager, well-known US concert promoter Barry Fey. A reputed incident where Robert allegedly refused to go onstage unless the band played newly written material may not have helped matters either.

By now Herbie and Columbia were coming to the same opinion: that Steve Perry would be the better option for Journey frontman. Matters accelerated when Herbie asked Steve to go out on the road with the band to get to know each other. Fleischman was unaware of his diminishing status within the set up, which resulted in an uncomfortable situation. Perry’s presence in the Journey camp was explained by passing him off as Jackie Villanueva’s Portuguese cousin.

“That really only happened one time,” says Perry. “I think it was when they were playing a show at Long Beach Arena, and I don’t think Robert was actually performing with the band – he was doing soundchecks with them. I think they had pretty much told him he was going to be the singer. I was also told that internally they were conflicted about it. I said to John Villanueva [brother of Jackie, and also part of Herbie’s management team] at the Oakland Coliseum,

‘Do you think this could really happen?’ And he said ‘yes’. So I was hanging around, waiting for my opportunity.

“Actually, it should be pointed out – and I only found this out a few years later – that the label had told the band that if they didn’t get a singer they were going to drop them.”

Gregg Rolie has some further insight.

“At the time Neal and I were looking for someone with more of an edge, but Herbie brought us Steve Perry,” he says. “We thought that he was a bit of a crooner and we were looking in a different direction. Robert is a great singer, but there was a lot of politics with the record company and various other things that took place there. They’re two very different singers.

“Steve actually came out on the road with us as my keyboard tech John’s cousin,” confirms Gregg. “We had to make the change, and it was a difficult thing to do, but Robert made a bit of a mistake. We were opening for ELP and he kind of made an ultimatum in Fresno, that he wanted us to play the new songs, but we were just trying to get the band across. We wanted to do the older material because it was more in keeping with the audience.

“He said he wouldn’t go on and that was a mistake on his part. Herbie made the decision right there to fire him. Nothing was really written in stone until that happened. For me, it’s now water under the bridge. I like Robert a lot and I liked what he brought to the situation. Robert has more of an edge but they’re both quality guys. It’s always a struggle.”

Did Steve feel that he had been forced upon the band by the label and Herbie?

“He [Herbie] said in essence, if not the actual words, ‘This is your new singer, deal with it,’” says Perry. “I don’t think I would have been in the band if Herbie had not just said, ‘Look guys, get used to it, keep going and shut the fuck up and write the music.’ Herbie and I have had a lot of artist/management collisions across the years.

"We accomplished so much together but it’s almost normal that artists and management have their issues. That being said, had it not been for Herbie my life would be profoundly different right now. He gave me my chance.”

Gregg: “In the end we made the right choice. Quite frankly, Herbie presented it as ‘this is your new singer’ and we were like, OK. And the fact is, he was absolutely right. Y’know, the proof is there.”

Did the band embrace Steve or were they a little apprehensive?

“You have to remember that the band had recorded three records and toured extensively,” says Perry. “Herbie was very talented in his ability to get that band to open for some very big acts – ELP and Santana – and play big outdoor shows. However, even though that was happening, they weren’t selling enough records. I think they wanted to make it on their own terms, so maybe it was a little weird for them to have to bring in a singer.

“Neal Schon was the guitar prodigy and stood centre stage. The group was built by Herbie around Neal, showing off his virtuosity. They had more of an instrumental Mahavishnu Orchestra thing going on, so it was a transition for them. Sure, I think we had our moments of difficulties with me being the new guy, so for a while I had to sort of walk on thin ice.

“It was a ‘let’s do it and see’ kind of attitude, and I had to prove myself, and I understood that, I really did. I can’t fault them for any hesitancy, because yes, they had a following before I joined them and they had fans out there that wanted the band to be successful as a fusion-based band with Gregg Rolie singing a little bit and Neal, Ross and Aynsley going off into fusion rock.

"When I joined I think they were concerned whether the fans would embrace me. Some did and some didn’t, and it was difficult walking out there. I remember one time we were in Paris I had a [camera] flash cube thrown at me and hit me in the eye.”

Gregg: “Perry wasn’t nervous, and if he was, it sure didn’t show. He knew he was good and he was co-writing a lot of the material. When you co-write, you get pretty comfortable about what you are doing, because it’s customised for you.”

How did Gregg Rolie feet about all this - he had, after all, been the band’s vocalist up until this point?

“I do believe in my heart that Gregg wasn’t that excited about the idea," says Perry, "but on the other hand he was certainly amenable and open-minded. We wrote Feeling That Way together, sharing vocals, and that was cool. In fact that’s the song where I would walk out on stage.”

From Gregg Rolie’s perspective, the situation was clear. “I expected to still sing a couple of songs here and there, but Steve was our lead singer,” he says. “I was stretched pretty thin playing four keyboards, harmonica and singing lead. With Santana I was the lead singer, and with Journey I was lead also. So, I’d never shared vocals before.

"I wanted to continue to do that – I looked at it like, well, The Beatles didn’t do so bad with four singers. So the more the merrier, and I still feel that way about it, but it just slowly got to be less and less.

“Eventually the band got built around Perry,” Gregg continues. “He came in at it slowly and it evolved into this situation where we were writing songs for an actual lead vocalist, which is totally different from where early Journey and Santana came from. Back then we had vocals, but it was really about the solo work and then, slowly, it became more about the lead vocals. It was great for me because I became a much better songwriter.”

It was the beginning of a new chapter for both of them. Blessed with an appealing personality, good looks and a voice from heaven, Perry soon became the focal point of attention. It was now time to unleash his talent in the studio by recording Journey’s fourth and pivotal album, Infinity.

The plan was simple: write songs, hire a producer, select a studio and make an album that would set out their stall for the next 10 years or more. Steve immersed himself in songwriting with all the band members, but mainly with new creative partner Neal Schon, eventually securing co-writing credits on eight of the 10 songs.

Steve and Neal struck up a strong rapport and quickly established a beachhead, strengthening the band’s sound and setting in place a new direction. The emphasis was now on fully formed songs with melodies, hooks and the sort of contemporary buff that made the competition quake in their boots.

The choice of producer was inspired. Band, management and label all agreed on Roy Thomas Baker, the flamboyant British studio craftsman who had worked with some of the most influential rock bands around, including Free and – most importantly – Queen.

After seeing the band live in Santa Monica, RTB (as he is affectionately known) and his trusted engineer Geoff Workman rendezvoused with the band at His Master’s Wheels Studio (formerly Alembic Studios), located on Brady Street in downtown San Francisco.

“They put me in a little apartment on Bay Street,” remembers Steve. “I went to SIR [Studio Instrument Rentals, a well-known rehearsal room] every day and wrote songs with band.

“Then, all of a sudden RTB comes in. We had enormous respect for him, because he’d produced Queen and Free. He was so much fun. The studio [His Master’s Wheels] had an old Neve console and a large tracking room, and the next thing you know he was really giving us a different sound.

“Neal’s doing what we called ‘violin guitars’. Roy had me stack all the vocals on a 40-track machine, and I really enjoyed that process. Also, Geoff Workman was so instrumental that we ended up grabbing him to do one of the records [Departure] without RTB.

“We rehearsed the material quite a bit before we recorded it so everything was ready to go before Roy got there. What Roy gave us was the opportunity to try different textures and ideas, but the foundational aspect of the songs and the arrangements were done. He really gave us a direction, and from there the band found itself.”

“I have fond memories of working with Roy and Geoff,” says Gregg. “Roy was very into experimentation, and quite wild in the studio. The multi-tracking of guitars and vocals was a brand new thing for us – all the layering. It was intense work. He created a sound which a lot of the guys didn’t like because it was so edgy, but I happened to dig it.

“Those tracks had a specific sound to them, which is what a good producer does. He was, and still is, a real character. Him and Workman both – they were fun to be around. Workman did a lot of the heavy lifting, inasmuch as getting things done.

“Geoff had worked with Roy for a long time and knew what he wanted. If Roy disappeared for a couple of hours, Geoff just carried on because he knew what they were doing as a team. We used the same team on the next album, Evolution. It got us on the map.”

Not surprisingly, the biggest impact was the quality and strength of Steve Perry’s vocals.

“I certainly discovered the depth of multi-tracking, as I never had a chance to work on a 40-track machine before,” says Perry. “I’d never had the ability to do eight root notes and then bounce them to one track, then wipe those and do the eight thirds, wipe those then do eight fifths and eight octaves and so on – and suddenly you have a big stack like on Anytime. When they are layered and smeared tight they just really block up. Roy knew how to do that.”

But despite the good vibes and enthusiastic progress, the glue soon came unstuck when a studio prank backfired…

“One night we went out for sushi and drank a bit of Sake,” laughs Steve. “Roy drank a little bit more Sake than most of us, along with a couple of the road crew. When they got back, Scotty [Ross, roadie] remembered a story about how Roy had once chased Freddie Mercury around the studio with a fire extinguisher.

“So Scotty decided to be funny and grabbed one of the studio extinguishers and chased Roy. Then Roy grabbed an extinguisher to reciprocate and fired it off, but it was one of those dry chemical types. The next thing we knew was that we couldn’t breathe – it had sucked the oxygen right out of the room and we couldn’t see in front of us for the smoke. So we ran outside thinking, ‘Oh my God, what the hell happened there?’ After a while we walked back in and the place looked like it had snowed, everything was covered in white powder. The problem was that the console, the recording tape and everything had this fine, very abrasive powder all over it.

“The Neve console was ruined. We had to quickly remove the tape because the dust would eat the oxide, so we moved to Cherokee Studios in Los Angeles to finish the vocals.”

With the album completed, a design makeover followed. The band brought in renowned San Francisco artists Alton Kelley and Stanley Mouse (real name Stanley George Miller). The duo had first hooked up with San Francisco’s counter-cultural doyens the Grateful Dead (designing their album covers) and legendary West Coast promoter Bill Graham (designing his gig posters). During the early 70s they had formed the Mouse Studio, and helped rebrand Journey by designing and standardising their cover art, including Infinity’s colourful flaming wings. The pair also came up with a Journey logo.

Says Perry: “Bruce Lundvall was the president of Columbia at the time, and he quipped that, in order for us to make another record with me singing, we would have to sell one million units. Hence the reason we stayed on the road for 298 shows that year. We started touring in February and didn’t come home for almost a year.

“Wheel In The Sky was the first single. Neal and I went to a pizza place, and I went over to the jukebox and saw a Wheel In The Sky 45 in that machine – an ecstatic feeling. I didn’t tell Neal, I just put two quarters in, pushed the button and sat down and the song started. Neal looked at me and started laughing. It was a monumental moment. Back then if you were starting to show up in jukeboxes it was a sign that you might be finally starting to happen. My mom had an eight track in her car and she would play the cassette to everybody saying, ‘That’s my Steven.’”

Although the tour emphasised the band’s growing stature, it also highlighted that while Aynsley Dunbar was an exceptional rhythm king, he was perhaps too complex for the way Journey’s music was developing.

“Van Halen were the opening act on the tour,” remembers Steve. “They were a brand new band back then. We were doing 3,000-seat auditoriums and they were killing us every night. It was eye-opening. We were keeping up with them, but they were certainly making us be a better band. They were so musically simple.

“Well, I was a drummer before becoming a singer and one of the things about being a drummer is that I’m kind of hard on other drummers. Foundationally you can have a really great band, but if the drummer doesn’t measure up you’re not going to do very well. But if you have a mediocre band and a great drummer you’re going to do better. So we’d do soundchecks and sometimes Aynsley might not be there or be off doing something like radio promotion and I would do soundcheck for him – set his drums up and play a few songs. It started to be apparent to Neal and to myself that the band sounded different with me because I’m a slamming R&B-style drummer, as opposed to a jazz-fusion drummer like Aynsley.

“Aynsley’s style had been perfect up to when the band changed style. As the music evolved, we started to work up some of our new ideas with me playing drums, and they didn’t sound as good with Aynsley playing them. So we toyed with that for a while, but occasionally we kept being reminded about it while jamming new ideas for the follow-up record. And then we saw Steve Smith playing drums with Ronnie Montrose, who was also one of our support bands, and we thought, ‘Help, what do we do now? Because this guy sounds like the cat.’ We started hanging out a lot – the next thing is we made a switch.”

Journey’s run of success continued with their follow-up albums, from Evolution through to blockbusters such as Escape, Frontiers and Raised On Radio.

Their continued uphill trajectory was an unprecedented triumph, propelling the band into increasingly larger arenas and stadiums, right the way through to the late 80s, before they implemented a (theoretically) indefinite and somewhat strained hiatus. With hindsight, the appointment of Steve Perry and the creation of the Infinity album was one of the pivotal moments in the development of modern rock.

“I liked the songs, I liked the edge and I liked the dual vocal stuff,” reflects Gregg Rolie. “The band had a lot of colour to it and I think we could have explored more of that. Infinity for me personally was a big change; writing songs for singing rather than writing songs for playing. The addition of harmonies and multi-track vocals… we’d never sung harmonies like that before.

“Also, the songs were great: Patiently, Winds Of March, Lights… Later it started going away from where I thought it should have been, but I’m only one member of the band so you’ve gotta roll with it. On Infinity there was still solo and instrumental work influencing how it sounded – it still had that vibe of being alive. It was always powerful. We actually carried that edge into the Evolution album.”

“If I had the chance I would do it all again exactly the same way,” says Steve Perry in conclusion. “I swear to God. I would not hesitate for a minute.”

Journey are on tour now. This article was first published in Classic Rock presents AOR, issue 11

Derek’s lifelong love of rock and metal goes back to the ’70s when he became a UK underground legend for sharing tapes of the most obscure American bands. After many years championing acts as a writer for Kerrang!, Derek moved to New York and worked in A&R at Atco Records, signing a number of great acts including the multi-platinum Pantera and Dream Theater. He moved back to the UK and in 2006 started Rock Candy Records, which specialises in reissues of rock and metal albums from the 1970s and 1980s.