Sonny Landreth: Sonny's Boys

Give slide maestro Sonny Landreth a glass cylinder and he’ll show you magic.

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Now, the Louisiana bandleader counts down the 12 slide gods who soundtracked his life, from getting spooked as a schoolboy by Robert Johnson to getting smoked at the Crossroads festival by Eric Clapton…

Lafayette, Louisiana, 1967. Neighbours wince, dogs howl and property prices tumble as an ungodly shriek blares from the Landreth house. “It was pretty brutal for my family,” chuckles the 64-year-old of his adolescent attempts at slide guitar. “I remember, I’d just get totally frustrated and throw the thing across the room. Slide sounds bad in the wrong hands, and all hands are wrong in the beginning. I, too, was very much part of that obnoxious tribe.”

Strange to think of it now. From his early sideman gigs with Clifton Chenier and John Hiatt, on to 1981’s solo debut Blues Attack, give this man a glass cylinder and he’ll show you magic. Idiosyncratic and eye-poppingly adept, Landreth’s zydeco-infused slide style has never sounded better than on new solo album Bound By The Blues, where it supercharges his originals and shucks fairydust over old chestnuts like Dust My Broom. Ask him if he’s ‘the greatest’, though, and the modest southern maestro gives an emphatic shake of the head. These, then, are the 12 slide galacticos who soundtracked Landreth’s life.

#1. THE EYE-OPENER

Robert Johnson

“Honestly, the first time I ever heard slide guitar, I didn’t even know what it was. I was pretty young – still at high school – when I first heard Michael Bloomfield play slide on the East-West album. Then I began to read about it, went back and listened to the early recordings by the Delta cats, pieced it all together. I really got drawn into Robert Johnson. A buddy got turned on to him first, called me up and said, ‘Man, you have to hear this’. I caught the title of Hellhound On My Trail and was, like, ‘Well, that sounds interesting’. Back in the day, in 1967, I had all of his original songs on this Columbia collection. This would have been vinyl, and I still remember the artwork of him looking straight down the camera. I began to hone in on the slide, which just had this air of mystery and anticipation. It just seemed like another person singing to me. There was a vocal quality that was haunting. And rightly so – it was a release in the face of adversity. As a kid, once you discovered one of these cats, you started checking out the others, like Mississippi John Hurt and Charley Patton, or digging further back into players like Tampa Red.”/o:p

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

#2. THE ELECTRIC WARRIOR

Elmore James

“From Robert Johnson, it was a quick segue to Elmore James with the electric guitar. Again, it’s that vocal sound: his guitar would just sing. He had that higher vocal range, and there’s an elasticity about his slide playing, because his songs were in those slack lower tunings. When I met Clifton Chenier, he loved my playing, because he was a big fan of Elmore James. Next thing you know, I’m out in a rice field in the country, playing this club, and they came from all over, men wearing suits, gals all dressed up. We’d play four hours and never take a break! It’s the biggest cliché of all, but my favourite song is Dust My Broom. The way that he took that, it embodied what Muddy Waters and the others did when they moved to Chicago and electrified the blues. Elmore had been doing that. There’s an electricity about that music. I’m sure people have the view that I have no business recording Dust My Broom on my new album. I was talking with Roy Rogers and he said, ‘Nobody needs to do that song any more’. But then I started thinking, what if you were to take it down a completely different road? So that was part of the challenge.”/o:p

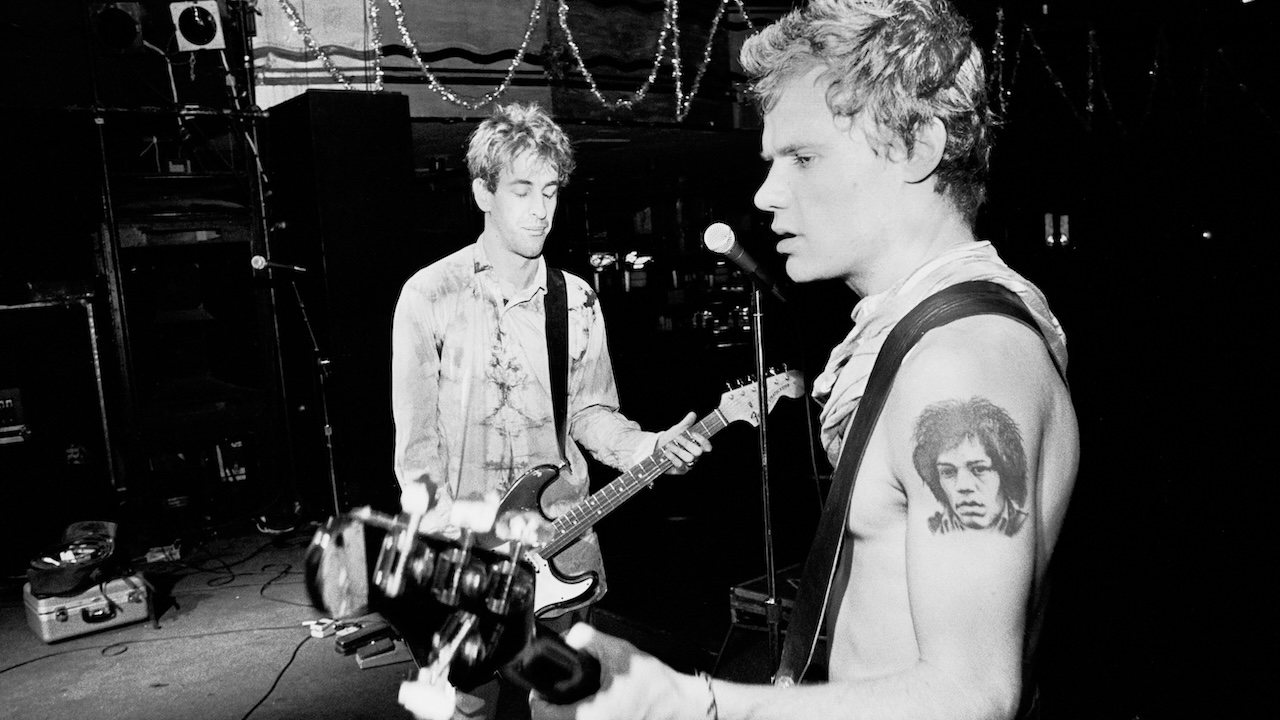

#3. THE ONE-TRICK PONY

Muddy Waters [pictured above]

“Muddy Waters only had that one thing on slide guitar, and he’d just change it up a little bit – but it was so soulful. It taught me to appreciate a variation on a theme. It was like his guitar was crying. I guess my favourite one was the Fathers And Sons album [1969], which had all the happening white cats at the time, like Mike Bloomfield, and they did all Muddy’s songs. It had that sleeve with the classic Michelangelo painting, where God is giving the spark of life to Adam – but it was a black God, and Adam is there with shades on! Wow. That was some statement, y’know? It got the point across. It also made me appreciate that what was happening was somewhere in our own backyard.”

#4. THE IMPOSTER

Clarence White

“Fast-forward to 1969, and there was the New Orleans Pop Festival, which was at a racetrack, of all things. Woodstock had already happened, and there was the Atlanta Pop Festival, so they had another one there in Louisiana. I was in the crowd when The Byrds came out. I could see Clarence White well enough, and from where I was stood, I thought he was playing bottleneck slide. It blew me away, and I knew I had to learn how to do that. I remember getting the album The Byrds had out at the time, and I set about trying to emulate that as best I could. It wasn’t until an album later that I heard the explanation that he had a string-bender on his Telecaster. So the joke was on me. But it pushed me to come up with ideas of how to get that sound.”/o:p

#5. THE SCHOLAR

Alan ‘Blind Owl’ Wilson

“Well, one of the earliest cats who moved it on in the 60s was Al Wilson. Canned Heat were, like, the ultimate hippie white-blues aficionados. These guys, they were so into the blues, way ahead of other people. They’d travel down from California to the southern states, looking up whoever was still alive from the early blues era, putting these cats back on festivals. Some of them had quit playing and they got ’em started again: Skip James was one of them. Canned Heat had hits, and it was unlike anything else on the radio. Al played smooth and melodic, and he’d trade off on guitar and harmonica, almost two versions of the same instrument. I started out playing trumpet, and because of that, you think about phrasing in a different way because you have to take a breath. So when I started to play guitar, I came at it from a different perspective. That’s what I heard in Al’s playing, too. They were also at the New Orleans Pop Festival. That was a heavy weekend. But that was right after Al had died, and Harvey Mandel was playing with them by then.”/o:p

#6. THE DOOMED GENIUS

Duane Allman

“Duane was the one that brought it all forward in the 70s. The Allman Brothers played the Blackham Coliseum here in Lafayette in 1970, when I was right out of high school, and that would have been right before he died. His reputation, of course, preceded him – and he blew me away. The way he played slide was so tasteful, but it made me want to go home and crank it up. It’s hard to beat Done Somebody Wrong or Statesboro Blues. When those came out on At Fillmore East [1971], it was transformative, really, for a lot of us. Of course, the downside is that then you hear everybody picking it up. Every bar band started playing it. But y’know what? That was a good thing. When I look back on it, in the early 70s, when the Allmans had those hits, you’d turn on the radio and you’d hear a two-minute guitar solo. And when would you ever hear that any more? Duane and Eric Clapton on Layla: that was real magic. It was almost like, Duane was just building up steam, and by the Derek And The Dominos album, it just exploded. To those of us following him, it was really exciting, because it brought together two camps that had such a profound influence on us white kids growing up trying to learn how to play blues guitar. There was Eric Clapton, the pinnacle coming from your part of the world. And then there was Duane Allman, from this part of it.”/o:p

#7. THE KINGPIN

Ry Cooder [pictured above]

“If you look back at it, and you go through the years, it’s really interesting, because there’s always the kingpin. If I have to pick one person from the 70s, it’d be Ry Cooder. I mean, he was the music, and how he employed the slide. His tone was just to die for. I don’t know that anybody will ever get a better tone. Ry did so much to elevate the art. Into The Purple Valley [1972] is one of my favourites of all time. I just loved his vision of slide guitar – the ‘big note’, as he would call it – and the way it came together with that voice and the acoustic fingerpicked parts, and these great arrangements and interpretations. He’s the ultimate.”

#8. THE CULT HERO

Lowell George [pictured above]

“There are some players that maybe people don’t really talk about, like Jesse Ed Davis. But for me, Lowell George was the under-appreciated slide player. He had the whole package. That cat was so unique: the slide sound, the big, soulful voice, classic songs, great producer. Back then, they didn’t have the technology like now, and I think that pushed for more creativity. People like Lowell George were making the most of all that, getting in the studio and creating sounds with a concept. The early Little Feat albums, they’re just classics. I actually met Lowell in 1975. By then, I’d made my way. I was on a tour with Michael Murphey, who had a hit out at the time called Wildfire, and we did a gig in Memphis with Dave Mason and Little Feat. We were all stood round in a circle, and I wasn’t that hip to Little Feat back then, and the band were talking it up about Lowell as they were getting ready for their gig. Then I heard him play, and I went, ‘Holy shit!’ The thing I loved was that he would just hold these notes out, like a horn player. He was one of the first to use a compressor and it just had this wailing, singular, melodic effect. It was very impressionistic. I’d never heard anyone do anything like that before.”

#9. THE ODDBALL

Gurf Morlix

“I was sat in with Lucinda Williams once, several years ago, and her guitar player was Gurf Morlix: very unusual name, very talented player. We go on live, and I played a solo, and then it goes to Gurf, and right in the middle of his solo – I didn’t even see it coming down until it was right above my head – this beer bottle appeared on a fish-hook. Somebody on the side of the stage had a fishing pole – y’know, a rod and reel – and they hooked on to the bottle and they would lower it down. So then Gurf just reaches up, without even looking, grabs the bottle with the fishing line still on it, and starts playing – and sounding good, too, y’know? That was hilarious. It just caught me off-guard. That’s got to be my favourite thing I’ve seen being used as a slide.”/o:p

#10. THE MEGASTAR

Eric Clapton

“He gets it. He got it from way back. You know, tapping into the emotional level of the song. Because that’s where it all comes from, the blues and all of this music that we love so much. It was the Concert For Bangladesh [1971] where Eric came out and played slide on My Sweet Lord – and it was perfect. He sure has been complimentary about my playing, and bless his heart for it. I love him to death. It’s interesting, because we had mutual friends for many years, but we didn’t finally meet until the Crossroads festival. We got to be friends. Eric has played on my projects – like From The Reach – and having him come out and play with us is just the ultimate. At the Crossroads festival [in 2010], we came out and did Promise Land together. Next thing you know, Eric kicks into a solo, and it’s another one of those moments where you go, ‘My God, is this for real?’ You could tell he was so ready to do it, man, and he just tore it up. It’s a good way to pull the rug out from under yourself!”/o:p

#11. THE CAT YOU GOTTA HEAR

Jack Pearson

“You gotta love Jack White. But another Jack would be Jack Pearson. Man, he is just amazing. He is so versatile, and has such incredible technique, and is so soulful. He did a stretch with The Allman Brothers when Derek [Trucks] stepped out for a time with his solo band. He and Warren Haynes were doing the duties. He was a Muscle Shoals cat, and he had common threads with a lot of those guys. Anyway, he lives in Nashville, and he can play classical, jazz, anything. Are you hip to him? You really need to listen to him.”/o:p

#12. THE GREAT WHITE HOPE

Derek Trucks

“He’s the best slide player I’ve ever worked with. I first met Derek when he was working at my friend’s studio down the road. He was still really young, but he was already doing session work. Right after that, he made his first album. I love everything about his slide playing. He’s the most soulful, he’s got the greatest vocal quality, he’s a terrific improviser. He can nail a part. He’s got a great ear. What’s amazing is that everybody thinks, ‘Well, okay, he got that from Duane obviously, there’s that huge influence’. But it’s way more than that. He took what Duane did and he’s just gone into the stratosphere with it. And it’s the fact that he’s broken down a lot of the genres of Eastern music, jazz, blues, rock, everything. I always thought there was a versatility to slide guitar, that it could be applied to any kind of music. It had that potential. At the last Crossroads festival, I did Congo Square with Derek, and it was like coming full circle. Eric really wanted Derek to play with us. He said, ‘I hope you don’t mind me breaking our tradition [of playing together]’. I said, ‘That’s okay’. And it was perfect.” /o:p

Bound By The Blues is out now via Provogue/Mascot./o:p

“I always felt like the blues was a universal language…”

Sonny on the genesis of new album Bound By The Blues.

“For a long time, people have been asking me when I would do a blues album again. Now just seemed like a good time. These days, I seem to go from one project and maybe go in a completely different direction for the next. So after working with an orchestra and doing instrumental compositions [on 2012’s Elemental Journey], it was fun to turn around and have a three-piece band. Y’know, just guitar, bass and drums, like we play every night, and just go in the studio and capture that. There was pretty much a direct line from the stage to this recording and it made for a really smooth transition.

“Where we recorded this album [in Lafayette], there was a big family living across the road from the studio, and they would get the Jambox out on Fridays and just get down, man. It was like a big party, every week. And then they’d hear me blasting on guitar in the house across the street, and they’d get into that, so there was this kind of dialogue going.

“Musically, I’ve never been at a loss for ideas. Songwriting is such a mystery. I have no idea where it comes from, but I’m always glad when it shows up. The instrumental, Simcoe Street, is named after a street in Lafayette that runs across town. It’s a street with a lot of life and colour, a lot of crazy characters walking up and down. I actually found my dog on that street 10 years ago, patched him up and named him Simcoe.

“That was a tune I had a long time ago and never finished. In fact, I had a demo of Simcoe Street for [2003’s] The Road We’re On. My co-producer said we didn’t need that particular song — and I agreed — but I never forgot about it. So I went back and reworked it, and once I knew I was going to record it, it pushes you to come up with ideas. That was probably the only song where I went in by myself and had a click-track going. Then my drummer showed up and he jumped on it, and we just improvised. A lot of that is just totally off the wall. Sometimes it happens best that way. You want that spontaneity.

“Lyrically, it always takes me longer. That’s much more of a pondering experience. But then again, that’s probably one of the most rewarding things. The title track is really about how, for all our differences, people are so much alike and we have commonality. I always felt like the blues was a universal language. After Hurricane Katrina and Rita, most of us down here have never been the same. I don’t mean that in a bad way. I actually mean that you overcome something with your friends, who were right in the middle of it, and all these experiences pull us together. I feel there’s a common voice in the blues that people understand, no matter where they’re from. It transcends language. It’s more about the emotional experience, you know what I mean?”/o:p

Henry Yates has been a freelance journalist since 2002 and written about music for titles including The Guardian, The Telegraph, NME, Classic Rock, Guitarist, Total Guitar and Metal Hammer. He is the author of Walter Trout's official biography, Rescued From Reality, a music pundit on Times Radio and BBC TV, and an interviewer who has spoken to Brian May, Jimmy Page, Ozzy Osbourne, Ronnie Wood, Dave Grohl, Marilyn Manson, Kiefer Sutherland and many more.