"We were just looking for a hit. And we heard the beginnings of a new kind of sound": Inspired by Australian pubs and riding a wave of optimism, Simple Minds made the album that sent them soaring

As the 80s dawned, Simple Minds were in crisis. But, believing that life was without limits, they recorded the album New Gold Dream and the dream became reality

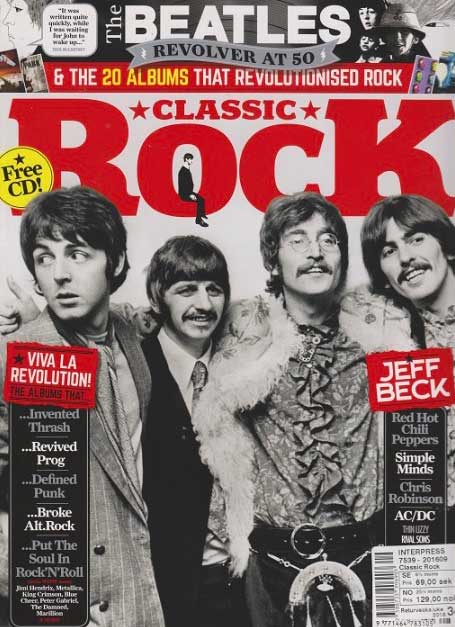

In 2016, Virgin Records issued a six-disc deluxe edition of Simple Minds' breakthrough album New Gold Dream (81–82–83–84). At the time, Classic Rock talked to frontman Jim Kerr, guitarist Charlie Burchill and producer Peter Walsh about an album that captured the band's youthful optimism and still resonates to this day.

“I remember this high-rise block we were staying in,” Simple Minds singer Jim Kerr says of his Glasgow youth, “and I loved staying in it because you could see the whole world from up there. And it seemed to suggest that there was a whole world out there, and stuff to experience, and stuff to get into. And we couldn’t wait. Mentally and physically, your world either ends at the end of your street or it begins there; your mind ends within you, or you’ve got a mind that wanders.”

‘Everything is possible,’ Kerr went on to sing in Promised You A Miracle, the single which epitomised Simple Minds’ unquenchable optimistic spirit and set them up to jostle with U2 for stadium success. Indeed the landmark 1982 album that song first appeared on, New Gold Dream (81-82-83-84), influenced heavily U2’s The Unforgettable Fire, as well as later bands such as the Manic Street Preachers.

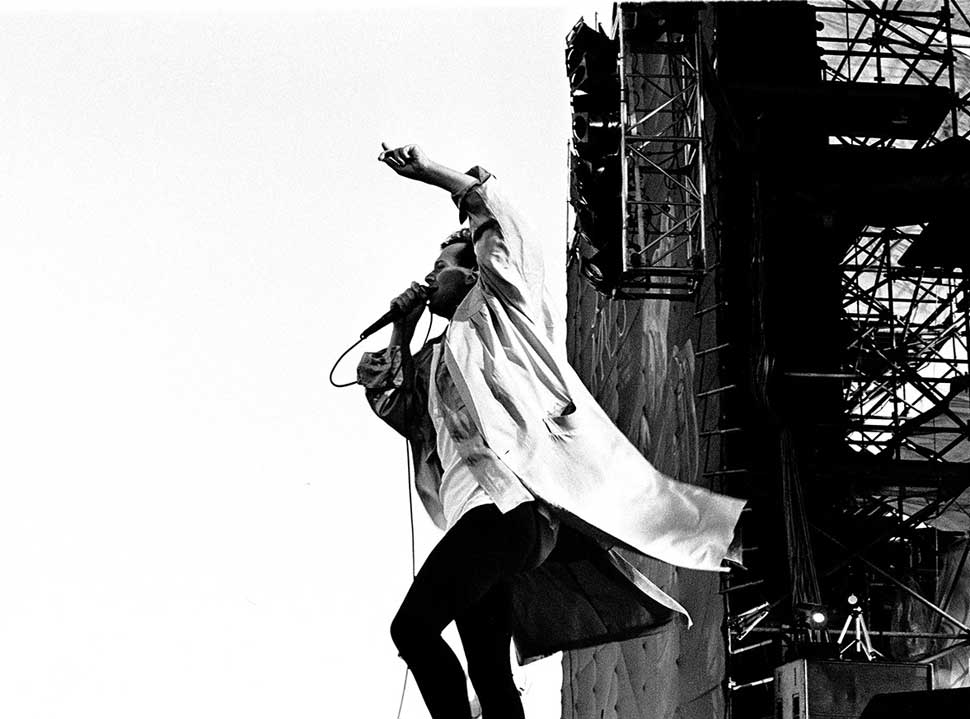

Now reissued as a lavish box set, New Gold Dream is the point of equilibrium between the cult synth experimenters Simple Minds were and the stadium rockers they became in 1985 after appearing at the Philadelphia leg of Live Aid and having Don’t You (Forget About Me) on the soundtrack to The Breakfast Club.

But such heights were dauntingly distant as the 80s began. The band’s first Top 30 album, 1979’s Life In A Day, hadn’t been matched commercially by its follow-ups on Arista Records: Real To Real Cacophony and Empire And Dance, which, though admired by the rock press for their cinematic, atmospheric strengths, saddled them with a ruinous £140,000 debt, battering morale. It would take a miracle, it seemed, for Kerr and his old friend, guitarist Charlie Burchill, to meet the dreams they’d set out from Glasgow to achieve.

“One of the greatest things that happened to us was to have the madness to believe, Charlie and I, that we could put something together that people would like,” Kerr says today, talking on the phone from Sicily. “Even in [their 1977 punk band] Johnny And The Self-Abusers we turned up for our first gig and people went mental. Charlie and I also had a hitch-hiking trip round Europe when we were seventeen, and the people we met and the things we did gave us a sense that anything is possible, if you get up and make the move.”

“Jim and I didn’t panic at Arista,” Burchill confirms. “And really quickly we managed to get [Virgin Records boss] Richard Branson up to Glasgow to listen to demos, and he signed us to Virgin. I never really had time to dwell on the fact that my drummer had left [Brian McGee was replaced by Kenny Hyslop in 1981] and things were not looking too good. Virgin were much more musical, cooler people. We made a really experimental double album, Sons And Fascination/Sister Feelings Call, and they never flinched.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Sons And Fascination reached No.11 but its single, The American, stalled outside the Top 40, leaving Simple Minds still without a hit song. But their potential was made clear on a revelatory Australian tour in October 1981, where Love Song hit the Top 10.

“We got our first gold record down there,” Burchill recalls fondly. “They had these big pubs you could play, with thousands of people. They were really hot and sweaty and quite mad. They felt really charged, and we fed off of that.”

For Kerr, “the penny dropped then, and we started thinking: maybe we can be pop stars as well. All that positive backdrop led us to the early writing sessions for New Gold Dream.”

For the next move, 20-year-old Pete Walsh, fresh from making Heaven 17’s hit album Penthouse And Pavement and with a CV as engineer which included Stevie Wonder, was suggested as producer. His work with Burchill remixing Love Song had already impressed the guitarist. Walsh went to see Simple Minds play in Liege, Belgium, and they made an indelible impression.

“There were four hundred people there, and it was quite goth but really electric,” Walsh remembers. “There was the atmosphere at the gig and also the atmosphere of the music, the way the keyboards and guitars were linked together. Texturally it was very cinematic, and I saw a colour in the sound, as well as the way they looked and the lights they were using. It was very vivid and very moody.”

Walsh met Kerr in his hotel room after the show. “He struck me as being more elusive than Charlie,” Walsh recalls. “A quieter figure, softly spoken, but very together, and really focused on what he wanted Simple Minds to be. For him it was a family. Foremost was how they got on together and how they enjoyed making the music. And like a family, he was very protective of the people in it and what it stood for. And it was obvious to me that there would be boundaries, that he would be keeping a lid on going too commercial. He was protective of the fact that they had a very unique sound.”

Kerr and Burchill, who had both just turned 21, seemed sharp, together young men to Walsh, not prone to fucking up. “They were very focused. They were also having a great time. And they weren’t worried in any way. They knew that they were good.”

The band had returned from Australia at the end of 1981. The 80s until then had been unremittingly grey,with rocketing unemployment at the beginning of Thatcherism reflected in a post-punk indie scene still in Joy Division’s bleak, stark shadow. But as 1982 began, Simple Minds noticed a welcome sea change.

Like 1965, when pop seemed to turn the grey country Technicolor, a ‘new pop’ movement turned up the brightness of the music. “If I think about ABC’s Lexicon of Love or New Gold Dream or The Associates, it was colourful music, colourful clothes, colourful everything,” Burchill says. “And when people started using ‘new romantic’ as terminology it all felt vibrant and flamboyant compared to the late seventies.”

As Walsh watched them in Liege, he began formulating how Simple Minds could benefit. “I taped that gig on my Walkman,” he says. “I wanted to capture that sound that I’d heard, that excitement. I thought their songs were ready-made with hooks and very melodic parts, but obscured by long arrangements. The idea was to cross them over into a more mainstream position. You have to come close to radio’s average sound.

"And everything on it at the time was vocal-led; Heaven 17, Human League, Spandau Ballet, ABC, Talking Heads, Roxy Music, Bryan Ferry and Grace Jones was what they were listening to – and competing against. And they were listening to bands like Can. Simple Minds sounded like a mixture of a lot of artists, and we were trying to give them their own identity. And ultimately that identity came from Jim. So I felt like Jim had to step up and compete. Which is where Promised You A Miracle came in.”

“There was a far brighter, more optimistic slant on what we were doing,” Burchill remembers of the music he and keyboard player Mick MacNeil started to write in January 1982 in the band’s default base, rehearsal rooms at Rockfield studios in Monmouthshire, Wales. “Promised You A Miracle was written then, way before the album. We were just looking for a hit. And we heard the beginnings of a new kind of sound. New effects and new amplifiers drastically changed the colour and played a huge part in things back then. The guitars are very distinctive on the whole album that followed, and very different to how I’d played before – cleaner, more melodic, lighter.”

Kerr’s exultant line ‘Everything is possible’ in Promised You A Miracle described Simple Minds’ mood then. “That’s how the music felt, and the language it brought out in me,” he says. “As soon as the riff for Miracle came up I wrote the lyric, and I think the vocal was on within seconds. Everyone at the record company said: ‘That’s a hit’, based on the song but also our momentum. Sometimes you get a song at the right moment.”

Quickly taped for a Radio 1 Kid Jensen session, Promised You A Miracle was done at The Townhouse studio in West London. “I wanted to make them more understandable,” Walsh says of his blueprint, “but still slightly out of focus, not to bring things out too much. We worked a lot on diction, and getting the hook lines and melodies repetitive and memorable.”

Released in April 1981, the single finally cracked the UK Top 40 for Simple Minds, peaking at No.13. Even as it climbed the chart the band were in The Old Mill, a church-like former pig farm in Fife, preparing music for what became New Gold Dream.

Simple Minds relished their belated Top Of The Pops debut. As with their earlier TV appearances, seeing them made a powerful impact on old acquaintances back in Glasgow. “I saw a really good mate recently who I hadn’t seen since those days,” Kerr muses. “And he said: ‘I hadn’t seen you for a couple of years. I knew you were messing about with a band. I was watching the fucking Whistle Test one night and there you were.’ It felt so strange to him. He couldn’t relate to it. There was no one we knew back then in Glasgow that had a record deal, or toured, no source of reference. It was like you’d gone to the moon. In some ways we had.”

Starting in May 1982, recording the new album began back in The Townhouse. “We’d work from noon until nine or ten and then go out,” Kerr says of their schedule. “Not so much clubbing, but to the great art-house cinemas London had then, where you could go at half-ten and see something obscure, and at least visually it would inspire a lyric.

"I always loved the German director Werner Herzog, and he had a movie at the time called Fitzcarraldo [about a deranged effort to, among other things, haul a steamship over a mountain in the Amazon basin]. In the film, actor Klaus Kinksi’s anti-hero declares: “It’s only dreamers who ever move mountains.” And that line brought Kerr out of his seat. “I loved the romance of that,” he says. “I loved the madness in it. And that line’s not a kick in the arse away from ‘Everything is possible’.

Some would see Kinski’s character’s ruinous obsession less positively. But Burchill is on Kerr’s side, neither man into half-measures: “You either believe in the dream,” he says, “or go for the mundane and banal, which is nothing changes, nothing happens.”

“Me and Charlie were also watching French films like Godard’s Alphaville,” Kerr continues. “That was a huge thing. So was Fassbinder’s Berlin Alexanderplatz and Jean Cocteau’s movies Fellini, Pasolini. It would all have been European, and giving us a sense of all the great stuff that was out there, even if much of it went over our heads.

“The books, too, like The Tin Drum and Camus – it wasn’t enough to have a record collection, you needed to have a book collection too. On the way to Australia, Charlie and I decided to get off in India, because we were reading Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children. We’d bitten off more than we could chew when we got there! But that’s how much all these things meant to us. Wherever we were, we were living it. And the songs come from everything that you’re taking in. People would give you stuff as well, and it all went into the pot.”

There were more fruitful discussions when Kerr and Burchill returned to the Columbia in London, an already notorious rock’n’roll watering hole, where the whole band were staying. There they’d find themselves in earnest discussion with the Teardrop Explodes’ Julian Cope, or ABC’s Martin Fry.

“Bands from the ‘provinces’ all started staying there,” Kerr explains. “It wasn’t a cool, posey hang-out scene, it was just people were busy, and they were coming back at night and playing you their stuff. We were all kin in that if you went through all our record collections… I’m not sure Martin Fry, say, would have been a fan of Krautrock, but he would have been a fan of Roxy Music. Then you had people like The The’s Matt Johnson, coming in and really sounding wonderful. Melody was a big thing. Everyone seemed to have a great tune. Orange Juice would come down with Rip It Up.”

Not that it was all cultural exchange and bon mots at the bar. “We had many mad nights at the Columbia. It was well-known for being riotous,” Burchill recalls. “People would end up making their own room service. But you need a gathering place, for stuff to bleed in.”

“There seemed to be more of an accent on… I don’t know if it was fantasy, but it was quite contrary to the Falklands, the later miners’ strike and all of that stuff,” Kerr says of his eager, razor-witted new generation. “[The Associates’] Billy Mackenzie was like a pools winner gone mad, spending all his money. This live-for-the moment thing was starting to be celebrated. Those times got a bad rap because of the yuppie phenomenon, and ‘greed is good’, and sometimes it’s hard to separate stuff.

"I don’t remember anyone in bands ever talking about money. But everyone wanted to be doing well, wanted the spotlight. I can tell you why we wanted it: because it wasn’t so long ago when we were drowning in debt and looking like we were about to get dropped [from their label], and playing to two men and a dog in Dortmund.”

Back in the studio, Walsh watched the crucial contributions of bassist Derek Forbes and keyboard player Mick MacNeil. “Derek played bass almost like a lead guitar,” he says. “His bass lines on the album were very melodic, very much like Joy Division/New Order. He influenced them in the end. Just looking at him playing was so elegant. It was like he was almost in a trance. And Charlie and Mick were great partners. Mick was an anchor for Charlie to weave in and out of.”

Also in and out were drummers, as Simple Minds’ drum stool continued to spin. Kenny Hyslop quit after Promised You A Miracle and was replaced by Mike Ogletree. Although Ogletree came up with the odd drum part on New Gold Dream he was felt to be too slow in the studio and soon relegated to percussion. He was replaced by Walsh’s friend Mel Gaynor (still with Simple Minds today). As a humane gesture from Walsh, the two drummers played the song New Gold Dream together, surrounded by a forest of mics.

Kerr watched the music being recorded from the control room, scribbling in notebooks, then listening back to tapes of it on each morning’s stroll to the studio.

“The music sounded fully fledged,” Kerr remembers. “A lot of it was pretty. Even the weather was bloody good. At weekends we played European festivals, and we would come back buoyant from that as well.”

“It was a great time,” Burchill agrees, “because we were jamming a lot, and Jim would have weird working titles, like Gold or Glittering or Summertime, defining the direction with a word or two. We let the songs develop slowly, but kept them short, and light. Later, when he sang, Jim could be introverted and thoughtful, a bit more gentle.”

The band relocated to The Manor studios in Oxfordshire for Kerr to complete lyrics and add vocals. Finally, only what became the title track was left to do. “I was meant to sing it one Friday, but I was playing for time,” he remembers. “It can feel very fragile when you walk up to the microphone if you’re not convinced of your idea. I sound-checked in a Swedish festival that Sunday, went back to the hotel, and convinced myself to finish it.”

He added the exhilarating chant from past to future in the chorus, ‘81-82-83-84’, that made it sound like the times belonged to Simple Minds – and their listeners. “It might have been one of those amazing sound-checks – like, fucking glorious,” he says, “and I probably went back feeling: ‘This is the dog’s bollocks, and I’m going to write this as though it’s the dog’s bollocks.’ This is where we are now, this is where we’ve been, and where we’re going.

“It sounds stupid and pretentious, but to me New Gold Dream sums up the paths that we had gone on on the first four records. Some with really dark moods, some intense, some claustrophobic. And the storm broke, and then the next day you have a beautiful morning. New Gold Dream, the title, the artwork, the language of a lot of the songs, resonates that to me.”

New Gold Dream still sounds like a classic album. Guitars and synths glisten and glide, retaining the cinematic scope and atmosphere of earlier albums. Although the singles sound anthemic, Kerr murmurs some lines, drawing you into the shadows. Released in September 1982, it reached No.3 in the UK. Promoting it in London, Kerr had to look at the trees in Hyde Park to remind himself which month it was, so fast were things moving.

He and Burchill have become well-rehearsed at apologising for Simple Minds’ eventually crass stadium years that followed, which lost old fans even as they gained armies more. “I remember even on New Gold Dream we were heavily criticised for sounding over-optimistic,” Burchill says, of an album that lifted your head out of dole queues, to the skies. “We were just feeling that it was all to be had if you really wanted it. And probably that led to hubris, and stadium rock.”

That may have been responsible for some misguided music. But optimism defines Simple Minds’ two main men, ever since they looked at the crumbling, violent Glasgow in which they grew up and saw only the possibilities on the horizon.

“I’m standing talking to you just now on a small terrace,” Kerr tells me. “I’m looking at smoke plumes coming out of Mount Etna. I’m still looking at these landscapes and thinking about what’s out there.”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 226 (August 2016)

Nick Hasted writes about film, music, books and comics for Classic Rock, The Independent, Uncut, Jazzwise and The Arts Desk. He has published three books: The Dark Story of Eminem (2002), You Really Got Me: The Story of The Kinks (2011), and Jack White: How He Built An Empire From The Blues (2016).