"Zeppelin wasn’t safe, but we had such a following that virtually everything was accepted" - How Robert Plant made peace with the end of Led Zeppelin

In 1982, Robert Plant gave his first ever post-Led Zeppelin interview, and Classic Rock's Geoff Barton was the man with the tape recorder

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

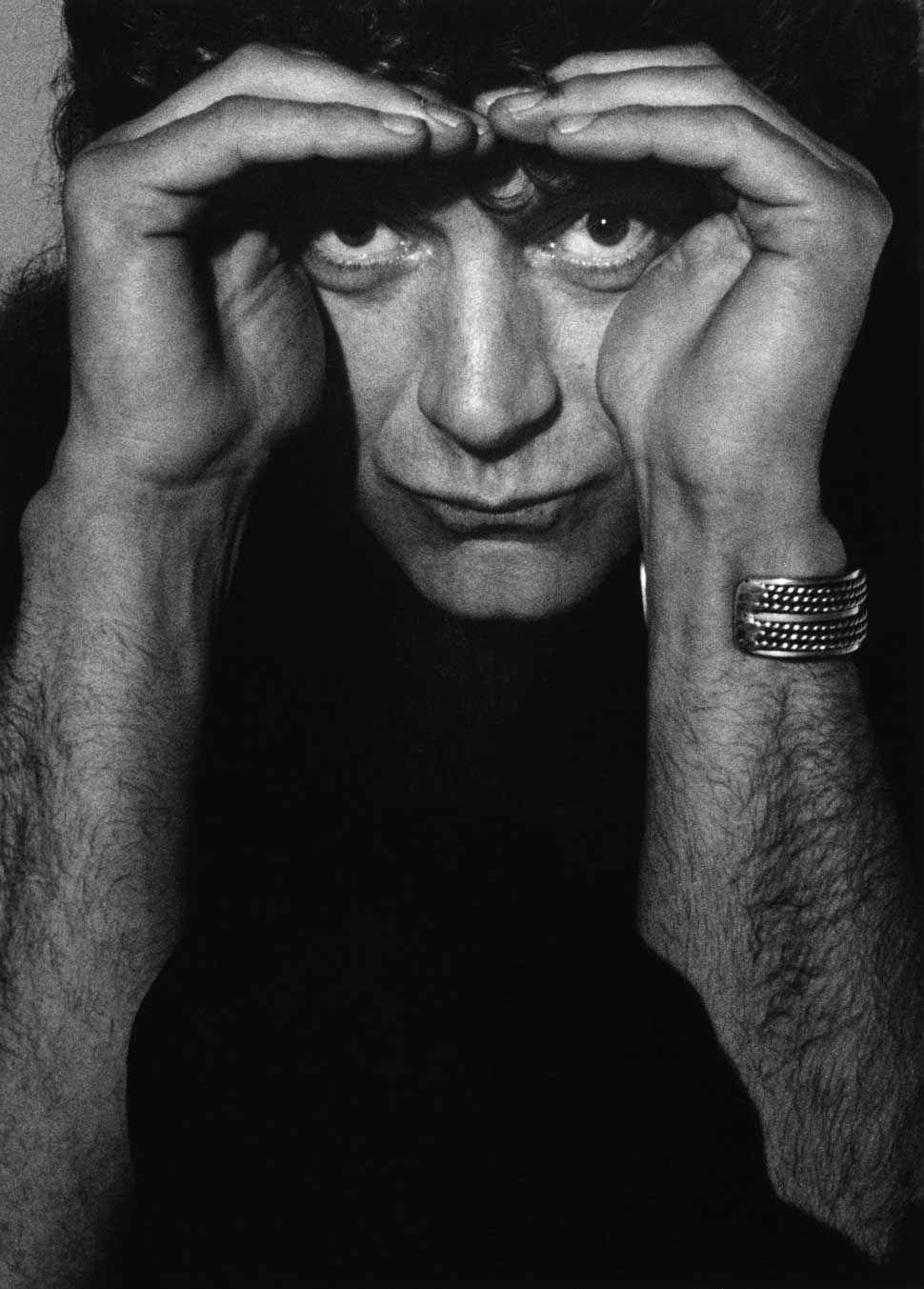

It’s a drizzly, overcast day in September 1982. I’ve just completed an interview with Robert Plant about his first post-Led Zeppelin solo album, Pictures At Eleven, and we’re standing outside Blakes Hotel in South Kensington conducting an impromptu photo session with Ross Halfin.

Belying his unapproachable rock god status, Plant is amenable and co-operative. He poses in this position and that, crouching low, stretching high, making my body feel brittle and stiff by comparison.

However, Plant has to apologise for not being able to straighten out an arm for one particular shot – the legacy of that car crash in Rhodes in August 1975 when he and his wife Maureen were seriously injured, which left Plant wheelchair-bound for a time and which caused an unexpected hiatus in Led Zeppelin’s career. Plant rolls up his sleeve and winces as he shows me his scars.

All too soon it’s over and we’re saying our farewells. As a parting gesture I present Plant with a picture I have of him performing a recent low-key gig at Dudley JB’s, in the heart of his beloved Black Country.

“Dear oh dear!” he cries. “Look at the bags under the eyes. I’ll tell you why that is: the show was two days after my birthday. I was just about beginning to sober up. And that hairstyle! I’d just had my hair cut. It looks like I’m wearing a soufflé.”

Right on cue, Halfin whips out a copy of his photo book The Powerage and turns to the back page. Lo and behold, there’s a photo of Plant in his classic long-haired screaming belter days, cavorting on stage with Led Zeppelin at Knebworth. You can’t help but compare the photos of the singer at Dudley JB’s and at the festival in 1979, and contrast the now with the then.

“Will you sign the book for me?” asks Halfin, impetuously. But Plant is only too willing and writes, with considerable flourish: ‘To Ross. It’s getting better! Robert.’ Plant goes to hand the book back, but he can’t tear his gaze away from the snap of him on stage with Zep.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

His eyes narrow, his brow creases and he says: “Oh, I don’t know. Shall I grow my hair again?’

He deliberates for a moment and finally exclaims: “Yeah, why not. To hell with it!”

Backtrack to a couple of hours earlier. Plant is leaning on the Blakes Hotel reception desk. Phone in hand, he’s muttering something about trying to acquire a copy of Billy Fury’s new single Love Or Money “for Jimmy”.

Compared to his flamboyant Led Zeppelin persona, it’s a more mature, subtly changed Plant that stands before me. The hair is short, his face is kinda lined and his manner of dress (zippy khaki jumpsuit and tattered white baseball boots) is quite anonymous.

We adjourn to the basement restaurant. Plant leads the way to a secluded annex he’s obviously had reserved for the occasion. We sit down on low, soft cushions and Plant pours tea and offers biscuits. On the table in front of him are a copy of Hunter S Thompson’s Fear & Loathing In Las Vegas, a Roy Harper tape and a half-finished pack of Winston cigarettes.

It’s a ‘lived-in’ scenario, and it occurs to me that Plant must have done a whole string of interviews today; that I’m just another blurred face on the journalistic conveyor belt.

“No, you’re actually the first person I’ve talked to,” Plant reveals in a surprisingly distinctive Midlands accent.

“That’s not too desperate,” I comment.

“No, there’s no desperation. Not really.”

Your album Pictures At Eleven has received good reviews. Has that surprised you?

I was expecting to get a hammering from everybody. I don’t really know why, because I’m proud of what I’ve done. But there’s been so much slating in the past when I’ve tried really hard, and I thought there wasn’t much chance of the album being well received.

Surely your years with Zeppelin must have rendered you immune to slag-offs?

This is different – I’m out on my own now. I could tell people were saying behind my back: “That’s it, he’s finished, he’s not going to come up with the goods at all.” All the time I was working down at Rockfield, no outsiders heard the record. But I knew what was happening, it was just getting better and better.

The most amazing thing was that so many people were pleased for me when they finally heard the record. People who I’ve known for years, people who run clubs in the Black Country. They heard the thing and just nodded their heads and smiled. They gave me their silent approval, and that’s just great.

They’ve known me for such a long time they’re not suddenly going to throw palm leaves at my feet.

How long ago did you start recording Pictures At Eleven?

Last September [1981]. Cozy [Powell, one of two drummers on the album, the other being Phil Collins] came back from wherever it was. He’d been off diving – either muffs or fish, I can’t remember. But anyway, it was last September and we laid down Slow Dancer and Like I’ve Never Been Gone.

And you released the album this July [1982]. Ten months – that’s quite a quick turnaround by Zeppelin standards.

Yeah… in fact we did those two first two tracks I mentioned in about a day and a half. There’s so much drama about Slow Dancer. It’s so brooding – and there was so much to prove, especially from my point of view. It just had to be right.

What exactly did you feel that you had to prove?

I just wanted to be responsible for something that was in that ilk. If I never write anything like that again… I just wanted it that way once more. Have a bit of that, then! And it worked successfully.

When exactly did you decide to go it alone and record your own album?

Well… obviously I was sitting on my arse after we’d lost John [Bonham]. I was thinking: “What happens next?” I had no idea at all.

Of course there was The Honeydrippers and all that, going round the clubs playing Otis Rush stuff, but that’s old hat. It was obvious that something would have to come out of it that would feed my craving… for… drama if you like, for mood, to expand mood beyond singing Stormy Monday – which, incidentally, I did very well at JB’s in Dudley three weeks ago.

Yeah. A few days ago a local photographer sent us a picture of you on stage there.

In fact Bonzo’s brother, Micky, videoed the gig and it’s really funny. We’d hardly rehearsed… but it was great for Robbie [Blunt, Plant’s guitarist], because since the record’s been made there’s been various rumours flying about, people saying: “No, he doesn’t really exist; it’s not Robbie, it’s Jimmy.”

Well, let me put the record straight once and for all: Robbie Blunt is a person in his own right and he is not Jimmy Page.

I don’t really see how people can think that; I don’t think Robbie plays like Jimmy at all. They’re like chalk and cheese. Jimmy’s very aggressive in his approach…

Did you consciously try to make Pictures At Eleven not sound like Led Zeppelin?

As you can imagine, I took a million pains to try and create my own individual sound. Halfway through the thing I stopped and said to Benji the engineer, a guy who was with us for years with Zeppelin, the PA man, I asked him: “Is it close? Because if it’s close we stop!” And he said: “Oh no, the mood’s totally different.”

I was just trying to pull away as much as I could… but then again you can only pull away so far. I wanted to leave Zeppelin the way it was and… just pull those reins a little to the right.

There are similarities, of course, but that’s got to be due to the fact that I’m singing and writing, and this is how I’ve sung and written since the beginning of time. Since we thought in black and white, really.

Just for the record, Led Zeppelin are dead and buried, aren’t they?

After we lost John we issued a statement to that effect but everybody read it as being ambiguous. I can’t even remember the wording of it now. But no, there’s absolutely no point. No point at all. There’s certain people you don’t do without in life, you don’t keep things going for the sake of it. There’s no functional purpose for keeping things going. For whose convenience? Nobody’s, really.

No one could ever have taken over John’s job. Never, ever! Impossible. I listen to Zeppelin stuff now and I realise how important John was. When he drummed he was right there with either my voice or whatever Pagey was doing… you couldn’t have found anybody with the same kind of ingredient to make the band really take off like John did.

For all the shit that hit the fan those many times… we all sort of rose out of it together going: “We don’t care – take this!” And you don’t start carrying on with people who weren’t a part of that. Impossible.

Does all that rule out any sort of collaboration with either Jimmy Page or John Paul Jones in the future?

It was always difficult to collaborate with Jonesy because he never listened to the lyrics. I used to talk about a song and he would say: “Now, which song would that be? And I’d go: “You know, the one on Presence.” And he’d say: “I’m sorry, I’m not familiar with the titles, what key was it in?” I’d sigh and say: “I haven’t a clue, Jonesy.”

But… I miss them. And I miss Jimmy a lot. But we’ve been pals for years and years, and we had a relationship that was built out of certain standards. Although we’re totally dissimilar, totally unalike, we knew exactly how far to take each other. When you’ve been with a bloke for 14 years you naturally miss certain parts, musically and personality-wise. But there’s a long way to go before I stop singing, and right now I’m having a great time with my own guys.

When you go on tour to promote Pictures At Eleven, what size venues will you be playing?

I can’t play places like Birmingham NEC. The only group I’ve seen come over reasonably well there was Dire Straits, and I’ve seen quite a few people, including Dylan, David Bowie and Foreigner. That size of gig is a little out of order now, in Britain at least. I mean, when Zeppelin played Earls Court in 1975 the sound was horrendous, but there was a kind of furious momentum about that whole gig that pulled us through.

I don’t think I’ve got the kind of audience that would fill the NEC anyway. I don’t know how I stand in the scheme of things, really.

In comparison to your ‘reclusive’ Zep days, you seem to be much more open and approachable now.

That’s because I’m prepared to work, I’m prepared to go out and I’m prepared to stand up and be counted. To me, everything is easy unless you make it difficult. And what’s the point of being difficult when music’s supposed to be a medium of expression and contact? Musically, Zeppelin wasn’t safe, but we had such a following that virtually everything was accepted… except people always wanted Dazed & Confused and didn’t want Fool In The Rain.

It’s great fun at the moment, very enjoyable. I’m learning new things every day, I’m meeting all kinds of new people in the business – and surprising them all, because they all thought I was some kind of demon.

Do you still like Welsh villages and all that? Bron Y Aur…

Bronnariar.

Is that how you pronounce it? I’d always wondered.

Yeah, I still like them. But I drive through them real quick.

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock 102.

Geoff Barton is a British journalist who founded the heavy metal magazine Kerrang! and was an editor of Sounds music magazine. He specialised in covering rock music and helped popularise the new wave of British heavy metal (NWOBHM) after using the term for the first time (after editor Alan Lewis coined it) in the May 1979 issue of Sounds.