Q&A: Alan Parsons

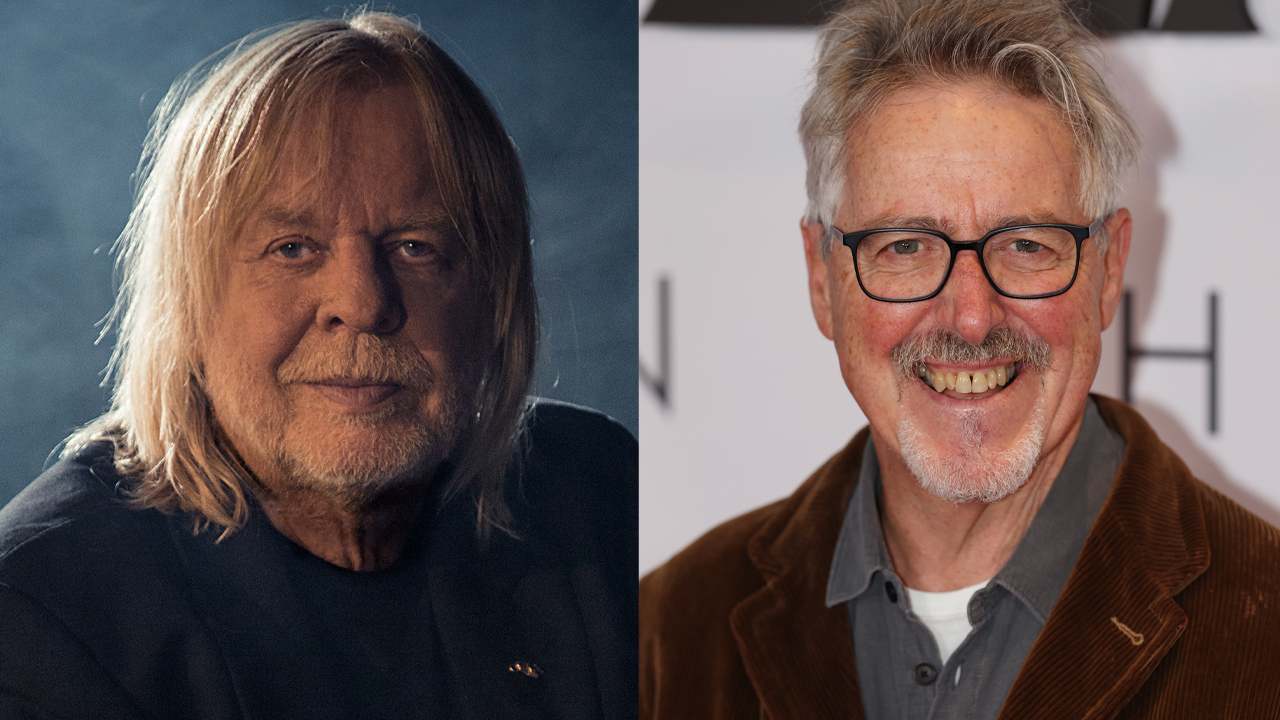

Alan Parsons turned down the chance to work on Wish You Were Here to launch his own band. Today Parsons discusses returning to play the UK and working with Steven Wilson.

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Over 12 years, The Alan Parsons Project released 10 successful albums and had seven Top 40 hits in America.

Parsons has also worked as a solo artist, as well as enjoying a hugely decorated career both as a producer and an engineer, collaborating with the likes of Pink Floyd, The Beatles and Al Stewart, in addition to his work with modern prog icons such as Steven Wilson. In March, he’s set to play his first British show in more than a decade, when he’ll be performing at the O2 Shepherd’s Bush Empire in London with The Alan Parsons Live Project.

It’s been over 10 years since you last played over here. Why has it taken so long?

You tell me! It’s not because I haven’t wanted to play in Britain, just that promoters haven’t called me. Finally, though, someone offered me the chance to come back and I jumped at it. I’d love to do more than the one show, but again it’s down to interest from the right people.

Will the set list this time span your entire recording career, or concentrate on specific albums?

It will mainly be material from The Alan Parsons Project albums, and there will be at least one song from each of them. I will probably do more from The Turn Of A Friendly Card than any other, and that will include The Turn Of A Friendly Card suite.

You haven’t released an album since A Valid Path in 2004. Any plans for a new one?

Sign up below to get the latest from Prog, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Nope, none. Is there any interest these days in a new album from someone like me? As with Peter Gabriel, Genesis or any other veteran acts, if I were to release an album, I’d get radio stations playing something from it once, and then they’d go back to Eye In The Sky.

Are you a studio musician first or do you prefer playing live?

Well, I started off playing guitar when I was 11 or 12 and was hoping to be the new Eric Clapton. But then I got a job as a tape op at Abbey Road and my chances of being a rock star went. For years afterwards, on my passport I had my occupation down as being ‘producer’. Now, though, I’m down as a ‘musician’. So, I think that answers your question.

You haven’t had a band partner since splitting with Eric Woolfson. So, how much input do the other musicians you currently work with have on the structure of the live performance?

Eric never played onstage with me. He wasn’t a part of the live activities, therefore his death in 2009 didn’t suddenly rob me of a touring partner. Now, I’m in change of what this band plays, and how we do it. However, I am lucky to have a good set of guys in the band, and if they come up with ideas then I will always listen. But I always work with a partner on the songwriting side. For instance, Fragile, which we put out in 2013, I co-wrote with the singer PJ Olsson. I would never write on my own.

You worked with Steven Wilson on his 2013 album The Raven That Refused To Sing (And Other Stories). Did you have much involvement in the way it sounded?

Oh, that was so much fun to work on. Such a brilliant bunch of musicians. What Steven said to me was that I should do things my way, and if he disagreed with anything, he’d let me know. But we got on really well and he was very receptive to my approach.

What criteria do you use when you’re deciding whether to work with an artist?

It can be any number of things. Firstly, it can be the strength of the songs. Then it might be down to whether they make me an offer I can’t refuse. Or perhaps I think working with them could really be positive for me.

The long-shelved The Sicilian Defence album was finally released last year as part of The Alan Parsons Project box set. How do you feel about it now?

The same as I always have. It’s not an album that has many saving graces. Why did I agree for it to come out as part of the box set? Because there was pressure on me from the label to include this. And Eric’s daughter, who runs his estate, had already agreed to it, so that meant I really had no choice. I’m not fond of the album, which we did in 1981, but it’s now out there, so people can make up their own minds.

Is there any more unreleased material in the vaults ready to surprise us?

I doubt it. There’s been so much material added as bonus tracks to deluxe editions of the albums that I think the well is now empty. Personally, I can’t think what attraction some of this stuff would have. Do people really want to hear alternate takes, and early versions of songs with some of the instrumentation missing? I think it diminishes the reputation of the band, but I suppose for diehard fans it means a lot. I can understand the appeal of including original radio commercials for albums – that’s interesting from a historical perspective. But much of the other material should have been left in the vaults. It makes me feel that we should have wiped it off the tapes in the first place.

Do you feel you get enough respect for your achievements as a musician?

I’ve no complaints. I suppose I’m regarded as being very low-key. I can walk about the streets carrying a Tesco’s carrier bag and nobody bothers me. And I don’t hanker after being trailed by paparazzi. It’s not that I crave anonymity, but obviously I don’t have the sort of face people remember. But other musicians give me respect for my influence on them.

Alan Parsons plays London’s O2 Shepherd’s Bush Empire on March 18. For more information, see http://www.alanparsonsmusic.com.

Malcolm Dome had an illustrious and celebrated career which stretched back to working for Record Mirror magazine in the late 70s and Metal Fury in the early 80s before joining Kerrang! at its launch in 1981. His first book, Encyclopedia Metallica, published in 1981, may have been the inspiration for the name of a certain band formed that same year. Dome is also credited with inventing the term "thrash metal" while writing about the Anthrax song Metal Thrashing Mad in 1984. With the launch of Classic Rock magazine in 1998 he became involved with that title, sister magazine Metal Hammer, and was a contributor to Prog magazine since its inception in 2009. He died in 2021.