How A Momentary Lapse Of Reason caused all-out war for Pink Floyd

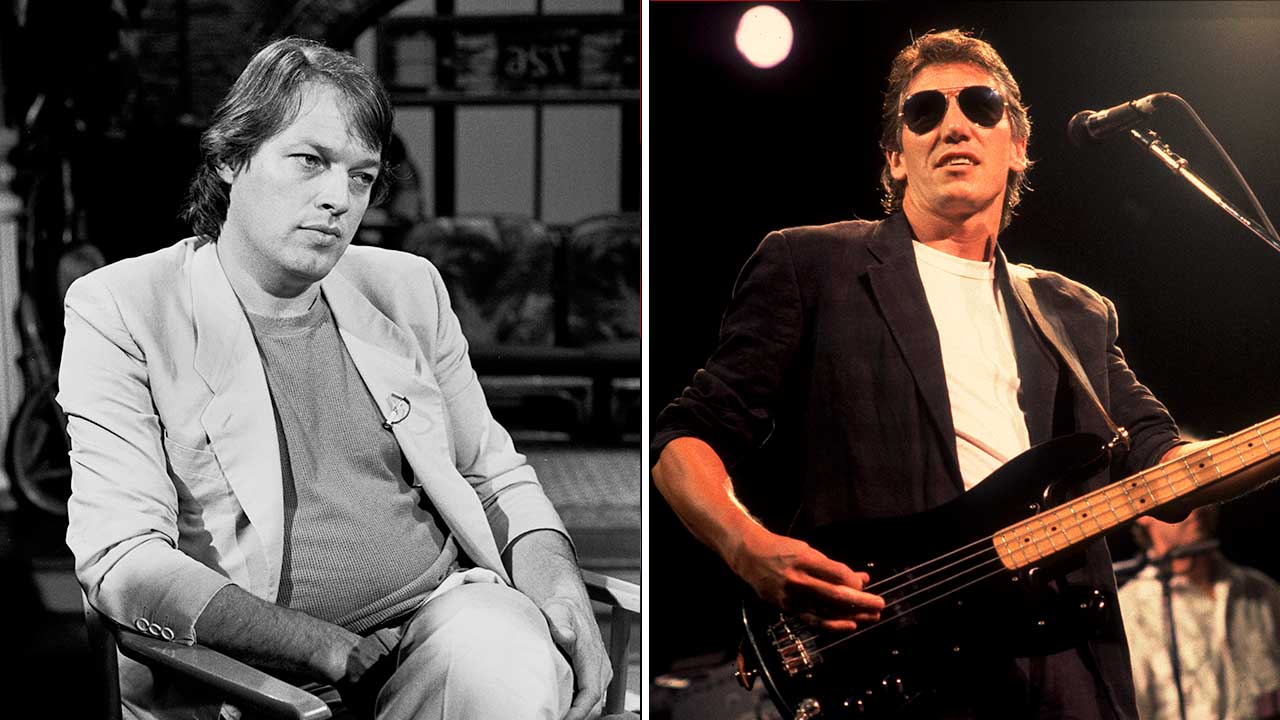

When Pink Floyd fell apart, Roger Waters took David Gilmour to court – and that's when the drama really began

As Pink Floyd all but collapsed following the release of 1983’s The Final Cut, fans could’ve been forgiven for thinking that the rancour between warring members Roger Waters and David Gilmour couldn’t have got any worse. But things were about to get nuclear.

It was the mid-80s and Gilmour and Waters had both recently released solo albums to mild success, but with Waters officially announcing that he’d officially left Pink Floyd, Gilmour saw a fresh future for the prog-rock pioneers. No matter that in Waters’ mind, his departure meant the end of Pink Floyd – for Gilmour, the idea of re-forming the band and making a new record without his overbearing bandmate was pretty much a dream come true.

Waters tried to see the plan off at the pass, taking out a high court application to ensure the Pink Floyd name could never be used again. Unperturbed, Gilmour proceeded to put a band in place – bringing drummer Nick Mason and keyboardist Rick Wright into the fold down the line too. Wright had been pushed out of the group during sessions for The Wall and, for legal reasons, would have to remain a salaried member for the new album.

Waters was furious, declaring that Pink Floyd was “a spent force creatively”. He took action against his former bandmates and label bosses at EMI Records, bringing the case to court in 1986 and sparking a furious war of words between the sparring members in the press. Waters lost, however – not that he accepted the verdict.

“My QC told me that the kind of justice I was after, I could only get from the public,” he said later. “The law is not interested in the moral issue but in the name as a piece of property.” He took offence, he said, at what he saw as Pink Floyd being turned into what he described as a “franchise”. “When does a band stop being a band?” he moaned. “They presumably have the same sort of definition as the people going round calling themselves The Drifters.”

Years later, Waters admitted to the BBC that he’d made an error taking Pink Floyd to court. “I was wrong. Of course I was. Who cares?” The damage was done, though, and you imagine that Waters had realised it was all self-inflicted.

The fiasco didn’t seem to have an effect on the album that became A Momentary Lapse Of Reason, unless the title referred to their former leader’s decision to drag the group through the courts. It was a record where Gilmour assembled a crack team of collaborators including Michael Kamen, producer Bob Ezrin, saxophonists Tom Scott and Scott Page, keyboardists Bill Payne and Joe Carin, drummers Jim Keltner and Carmine Appice and more to craft an atmospheric, ambient rock album worthy of the name. It was a huge success, selling in its millions.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Waters disparaged the first Pink Floyd album without him as “a pretty fair forgery”. And in many respects that’s exactly what it was. A Momentary Lapse… was as much a David Gilmour solo album as the The Final Cut had been a Roger Waters solo album.

Never the most prolific lyricist, other collaborators were brought in to find the right words to Gilmour’s new songs. Eric Stewart of 10cc was invited to try his hand, as were the Liverpudlian poet Roger McGough and Canadian songwriter Carole Pope, but nothing really stuck. It wasn’t until Gilmour invited Anthony Moore, founding member of 1970s British prog pioneers Slap Happy, to come up with some verses that things finally began to click.

Gilmour found the musical motif for the album he was looking for when Ezrin decided to record the sound of the River Thames outside the Astoria, one foggy winter morning, along with the sound of a creaking rowboat. The recording was then used as the album’s instrumental overture, Signs Of Life. The metaphor of an unending flow of water, of energy, of life, would become a lasting one for the new Gilmour-led Pink Floyd.

Given that Waters was gone and neither Mason nor Wright had more than minimal involvement, A Momentary Lapse Of Reason was the most Floydian-sounding Pink Floyd album since Wish You Were Here a decade earlier. The ambient sound effects and spectral keyboards were back, as were the back-arching guitar and pattering-rain drums. The vocals no longer sounded like they were being dredged from the bottom of the ocean, but had regained the ethereal textures of summers gone by.

Ultimately then, the fact that Pink Floyd’s principal lyricist and dream-weaver, Roger Waters, was nowhere to be heard made not a jot of difference to the millions who bought the new album. The fact that Pink Floyd at their greatest had always been anonymous, in terms of image, working entirely in their favour again. No one missed Waters unduly because, at their peak, nobody had ever thought of him as standing out from the others. The new Floyd album even had one track, Dogs Of War, that could have come straight from Waters’ corresponding solo album released that same year, Radio K.A.O.S..

There was one big difference, though, that everybody did notice: Radio K.A.O.S. barely reached the US Top 50, and limped to No. 25 in the UK. A Momentary Lapse Of Reason shot to No.3 in both the US and the UK charts. It was much the same story around the rest of the world. Decent enough reviews for both albums, but relatively modest sales for the Waters release, while the new Floyd sold in millions, picking up gold and platinum albums in a dozen different countries.

When the two camps then found themselves touring America at the same time, it was clear who the victor was going to be. Waters’ tour found him performing in modest-sized theatres, many barely half full, while the Floyd tour encompassed 200 high-profile arena dates resulting in over 5.5 million ticket sales. “I’m out on the road in competition with myself,” groaned Waters, “and I’m losing.”

Gilmour responded by telling the respected British writer Phil Sutcliffe: “I’m 40. I’ve slogged around America, Europe and the rest of the world to get the group off the ground. But I don’t feel old except when I think about starting all over again without the name Pink Floyd. I’ve earned the right to use it.”

He was also magnanimous in his appreciation for everything Waters had previously brought to Pink Floyd. Yes, there had always been rows between the two men, “but the rows were all about music,” he insisted. “I can also remember me and Roger sitting in the studio, going, ‘Wow, this is fantastic, what we’ve just done’. But Roger’s dominance did become an issue. I don’t think he consciously wanted to do people down, he was just being himself. Sometimes it’s hard to be sensitive to how much your characteristics can hurt other people. Also, everybody who got damaged by these things was as much to blame for it at the time as anyone else.”

Within three months of the ever-extending Floyd tour, both Mason and Wright had been fully reintegrated, too, as if to underline just how ‘real’ this Pink Floyd was. “Their confidence was restored,” Gilmour explained. “That tour brought them back to being functioning musicians. Or you could say I did.”

With the tour still going strong a year later, a five-night stint at New York’s Nassau Coliseum was recorded in August 1988 and mixed the following month at Abbey Road. The result was Pink Floyd’s first live album in almost 20 years, Delicate Sound Of Thunder, released in November.

By then, though, the war between both sides was temporarily over – legally at least. Two days before Christmas 1987, Roger Waters officially accepted an out-of-court settlement from David Gilmour’s legal team, withdrawing any challenge to Gilmour’s use of the Pink Floyd name, in exchange for his retaining of full rights to the concept of The Wall.

There were, however, several small but typically exacting demands, such as an $800 per show fee for the band’s use of the inflatable pig. For the 1987-88 Floyd comeback tour, Gilmour had already had pink testicles added to the original sow devised by Waters, thereby rendering it sufficiently different from the original Floyd pig.

Asked around this time what his artistic purpose would be now he no longer retained any say in the future of Pink Floyd, Waters responded caustically: “There is no purpose. We do whatever we do. You either blow your brains out or get on with something."

Niall Doherty is a writer and editor whose work can be found in Classic Rock, The Guardian, Music Week, FourFourTwo, Champions Journal, on Apple Music and more. Formerly the Deputy Editor of Q magazine, he co-runs the music Substack letter The New Cue with fellow former Q colleague Ted Kessler. He is also Reviews Editor at Record Collector. Over the years, he's interviewed some of the world's biggest stars, including Elton John, Coldplay, Radiohead, Liam and Noel Gallagher, Florence + The Machine, Arctic Monkeys, Muse, Pearl Jam, Depeche Mode, Robert Plant and more.