Kid Rock: American Hustle

He’s been a motor-mouthed rapper, nu metal icon, unlikely Nashville country star and now a blue-collar heartland rocker. So will the real Kid Rock please stand up?

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

When Kid Rock isn’t living in a trailer in one of the smallest towns in Alabama, or in the Nashville heartland of his surprising country fan base, he can be found off a long dirt road in Michigan, about 40 miles north of Detroit, not far from Romeo, the village where he was raised. As the car I’m in noses uncertainly through heavy morning mist, I catch glimpses of countryside which will be lovely when the leaves return, and the spread-out houses of a solidly prosperous middle-class town. We’ve been told we’ll know Kid Rock’s house by the wild turkeys in the yard.

It’s not really the setting you’d expect for one of the last rock stars left standing in the US charts, 25 million sales down a line of success from 1998’s Devil Without A Cause to his new, tenth album, First Kiss. Kid Rock has made hairpin musical turns along the way, from Devil Without A Cause’s furious rap-rock to his country ballad Picture, a 2002 hit with Sheryl Crow. Rock’N’Roll Jesus, from 2007, and its massive single All Summer Long – with a chassis built from Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Sweet Home Alabama and Warren Zevon’s Werewolves Of London – established the man known to his friends as Bobby Ritchie as a classic rock craftsman, heavily influenced by Bob Seger, southern rock and country songwriting. An ad for First Kiss lists his career’s telling range of collaborators: Slash, Seger, Crow, Sammy Hagar, John Fogerty, Eminem, R. Kelly and Hank Williams Jr.

Most people’s image of Kid Rock, though, is summed up by a less radio-friendly single: 2002’s You Never Met A Motherfucker Quite Like Me. He burst on to MTV with a fur coat, shades and cheroot, straight out of Early Mornin’ Stoned Pimp, one of his four pre-fame albums. He’s been a hard-partying, don’t-give-a-fuck rock star of the old school, an anti-gun-control, hunting pal of his fellow Michigander and (much more extreme) right-wing Republican Ted Nugent, serially in court for swinging fists in bars, and witheringly indifferent to anyone’s opinion but his own.

During my time in Detroit, everyone seems to have a story or view of Kid Rock. A waitress recalls an uncle in Romeo shuddering when wild man Bobby would turn up at parties, trouble trailing in his wake. A cab driver despairs, in graphic terms, of the Kid’s judgement in marrying Pamela Anderson; a brief, stormy affair which gave him tabloid fame.

“Kid Rock – wasting his time with that ho Pamela Anderson,” he chides. “You can’t change a ho like that. Married for one year, 2006-2007. That ho wasted his time. He shoulda just fucked her. He coulda had her fake titties swingin’ in his face anyway.”

Back on Kid Rock’s road, a shadowy figure looms in the fog like something out of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, to flag us down his drive. A solid metal gate and the private Allenstown Roadhouse behind it show we are, after all, in rock star territory. A large framed photo of country music icon Hank Williams is in the porch of the studio building. A poster for a Kid Rock/Lynyrd Skynyrd show is in the corridor to the studio itself, which is big enough for a band to record live in. In the lounge there’s a small snapshot of a youthful Kid with Keith Richards, alongside paintings of Hendrix smoking spliffs.

“Where are the wild turkeys?” the PR asks.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“You’re looking at one,” Kid Rock says.

Kid Rock makes his own coffee from a Starbucks machine. There’s no question of some underling doing it for him. He’s wearing a T-shirt, jeans, and a trucker’s cap over his long hair; his lightly tattooed arms are the only sign this 43-year-old was ever unrespectable. It’s 10am, the start of a day of promo business he admits he has little patience for. At least when he recently took another reporter out to Alabama, he got to freak him out by “murdering” three wild pigs he’d caught, pausing only to decide whether to “stab or shoot them” before the blood flowed in front of his shaking guest.

“This weekend we had a great time,” he says, stifling a yawn. “But last night I took a sauna, went to bed early, because I wanted to be fresh for today. I don’t wanna sit here and make us fucking hate this. Because I already don’t like enough about this part of it. I just don’t know how much I have to say any more. It just doesn’t seem that important any more. I try to look at it like, ‘Okay, you rich, spoiled asshole, quit bitching. Go out and tickle some balls.’ I’ve always been proud that I’ll play the game, I’ll tickle your balls a little bit. But I’m not going to suck your dick.”

Which is a relief. Apart from pride in his music, one motivation for this former wild child carrying on is, he explains, pension plans for Twisted Brown Trucker, the backing group he modelled on Bob Seger’s Silver Bullet Band.

“Me and my band are like a family,” he says. “I still work pretty hard because I want to take care of them, and the people around me. I’m fine. But I think by the time I’m fifty I’ll have them set up. I made a lot of hard decisions to run my business a certain way, so we can keep going for a long time. When the first album came out, and you looked at this handful of groups [in nu metal’s early days] and asked: ‘Do you think Kid Rock’s going to be the one twenty years from now still going?’ they’d have been: ‘Fuck no!’ But we’ve paid people fairly and made smart decisions because I need some fuck-you money. So if someone comes to me and says this is the way it is, I can tell them to go fuck themselves.”

It’s a long-term business plan his dad, Bill Ritchie – who ran two prosperous car dealerships in Detroit, and raised Bobby and his three siblings in a house in rustic Romeo complete with pool, tennis court and orchard – would surely approve. The 50-acre spread we’re sitting in now (plus the other ones scattered around the States) is his dad’s success writ large. An early Kid Rock song, My Oedipus Complex, laid out his resentful relationship with his apparently dominant, unfeeling father. First Kiss, though, finds the middle-aged Kid nostalgic for small-town life, notably on the wistful Drinking Beer With Dad.

“I’m real proud of that song,” he says. “My dad was a big deal in a small town. Very prominent in the church, always liked to throw fun parties. If you met my dad and hung out for a while, you’d say: ‘Kid Rock makes a lot more sense now’. He likes to have a good time and fucking talk shit. But we used to butt heads when I was a kid. I’m looking at being a grandfather now [his son Bobby Jr is 20 years old], and I look back on those times now and we were almost throwing fists at times.

“Like a lot of dads, he had a plan: go to school, and get into the family business, this car dealership, go to church on Sundays – be a fucking normal kid. And I was far from a fucking normal kid! At that point, coming home with your hat sideways and ten black kids every weekend… this wasn’t the plan,” he laughs. “So they were freaked out. And I was hurt that they couldn’t support me, and he didn’t want any part of it.”

Bobby ran away from Romeo to Detroit when he was 15, following his first dream of being a DJ and rapper. Sitting here aged 43, is it hard to remember what he was so mad about?

“I just wasn’t going to follow the rules,” he says. “I knew I wanted to do music, and it was very difficult to get it done in my bedroom. I needed to be somewhere else, instead of butting heads at home. Like when I wouldn’t go to my brother’s drug rehab programme, where I got kicked out of there for telling them to suck my dick when they wanted to talk about feelings. I still have the same attitude. ‘Let’s see a shrink and talk about our feelings…’ Fuck that! Let’s lift the rug up, let’s sweep ’em all under there, and let’s fuckin’ forget about it. I don’t need this fucking ‘let’s get it all out in the open.’ Fuck that. If it’s not on a song, we’re not having a conversation about it, on any level. You know what I mean? Things happen, it’s just life. Deal with it. Quit cryin’. But, you know, I learned a lot from all those experiences. So I don’t regret anything. Everything seems to have made sense, coming to where I’m at now.”

I mention that I’m considering looking around his old home town later. “Fuck,” he says, “tell me what it’s like. I haven’t been there in a while.”

Romeo, Michigan, is the last place on earth you’d expect Kid Rock to come from. Thirty miles away, much of the Detroit he left it for remains pocked with fire-blasted homes, and whole blocks simply erased by frightening neglect in the wake of the 1967 race riots which sent whites running to the suburbs.

Romeo, the furthest, most rural suburb of all, is more like the Cotswolds than the ghetto. It’s a faithfully preserved 19th-century village, many of its hundreds of large, eccentrically irregular clapboard houses from the pre-Civil War era. Some especially dark and old residences, eerily lit only by Christmas candles, recall the motel run by another famous Midwesterner, Psycho’s Norman Bates. Amid the antique shops, estate agents, large churches, lavish kerbside nativity scenes and library, there’s even a village green, complete with a holly-and-ivy-bedecked bandstand. Everyone’s white. It’s the sort of idyllic spot people like Kid Rock’s dad run away to. But after half an hour experiencing its unrelieved, preserved prettiness, you start to see his son’s point. Still, the almost wholly black, economically devastated Detroit he moved to in the 80s must have been a shocking contrast. Was he out of his depth?

“Oh yeah, of course,” he laughs. “Being white! But I learned at a young age that the more I was myself, the more people accepted me. It also didn’t hurt to be a very good DJ – to be able to do something in the culture that people were in awe of. I felt like I was supposed to be there. But I also wasn’t supposed to be there forever. I came from a really good, upper-middle class family. So that was a weird feeling, knowing that I could get out, when other people here don’t have that opportunity…”

Kid Rock the Republican believer in the American Dream suddenly corrects himself. “They’ve really got to work hard to create that opportunity.”

Was he ever frightened?

“Yeah. There were a few shoot-outs that I was in the middle of. They were not fucking fun. I remember one time, these kids came from Detroit, and they got in my shit, started pushing me around. I didn’t want to DJ any more, and I went to this girl I knew’s mom’s house – we called her Mrs Flo. She was an older woman, sat around in a robe drinking beer. And a couple of my friends in the hood got into it with these kids, and they were like: ‘Don’t fuck with him.’ A kid pulled a shotgun out, it got crazy, and fists were being thrown, and I felt it was because of me and I didn’t want to go back. Mrs Flo put a thirty-eight in her fuckin’ robe, and she was like: ‘You’re going back to that party. Follow me.’ She walked outside, with a fucking pistol, and said: [cranky Southern voice] ‘Who’s fucking with the white boy?’ Made me go back in the backyard party and DJ some more. That was scary.”

Kid Rock was trying to make it as a white rapper like his later Detroit friend Eminem, and dealing drugs on the side. But by the time of his second major-label deal, with Atlantic, the need to get booked at venues fearful of the violence that rap was believed to attract meant he also had a band. His fourth album, Devil Without A Cause, was a rap-rock hybrid which hit just as nu metal stormed to dominance. Its anthem, Bawitdaba, was dedicated to ‘all the crackheads…/And all my heroes in the Methadone clinic.’ Listened to now, especially next to the relatively sedate First Kiss, that album boils with anger.

“I was angry at that time,” he says. “I was fucking pissed. No one would listen to me. I was at the fucking end of my rope. I had a young kid, and I didn’t have any money. I knew what to do with music. When the Korn and Limp Bizkit stuff was happening, I was like: ‘I can do that in my fucking sleep, a hundred times better.’ So I did.”

But Devil Without A Cause also had songs showing how he’d pull the escape chord as nu metal crashed and burned. “I wanted to make more melodic music,” he remembers, “instead of Bawitdaba, which is just hard fucking attitude that gets you riled up. I really enjoyed key changes that made you feel something, made a song go to a different place. So [on Devil Without A Cause] I still went places like Cowboy and Only God Knows Why, hoping that I could take something further. Looking ahead. I’d love to grow old in music gracefully, the way people like Bob Seger and a lot of country artists have. I don’t want to be sixty-five years old and the only thing I can do is Bawitdaba. I always wanted to play my age. And as you grow old you change. And it’s definitely changed the music, no question. I wasn’t thinking about writing fucking [softer, socially conscious songs] Care and Amen when I was fucking twenty-six. The first time I came to Britain, they put it on the front of a newspaper that I said: ‘I came here to snort cocaine, fuck bitches and play rock’n’roll.’ And everyone was kind of up in arms about it. And I was like [shrugs his shoulders] ‘I told the truth.’ That’s where my head was at then. Not these days.”

His most unlikely move away from his rapping past was into the country music he’d always skipped in his parents’ record collection. Growing to appreciate the music’s “fucking well-made songs”, he worked with Hank Williams Jr, the iconic, ornery son of the music’s most famous name.

“I got a lot of really weird looks,” he remembers, “because I walked into that world holding Hank Williams Jr’s hand. I could see it on people’s faces: ‘Out of all the people, he’s walking around with him? The crazy rap kid who does rock and stuck his hand in the country cookie jar?’ And I felt like someone had drugged me and I woke up in the country world – ‘What the fuck happened?’ It was as much of a shock to me.”

Straight-ahead classic rock, though, is where Kid Rock is really at now. The lead single from his self-titled 2003 album was a cover of Bad Company’s Feel Like Makin’ Love. The Rick Rubin-produced hit album Born Free (2010), made with members of Los Lobos and Tom Petty’s Heartbreakers, sealed his shift from rebel rapper to beloved heartland rocker.

“I realised I could never be like my heroes in that world: Bob Seger and Tom Petty and the Eagles,” he says. “Making good blues-based rock’n’roll music has been the hardest fucking thing for me to do. I think I’ve started to nail it a couple of times – with Born Free and this new record. I know there’s raves going on with thousands of kids having the greatest time all over the world, and that’s great. But I still don’t think you’re ever going to beat a good blues-based rock’n’roll song. Rock’n’roll’s borrowed from everything. It’s a melting pot, like America.”

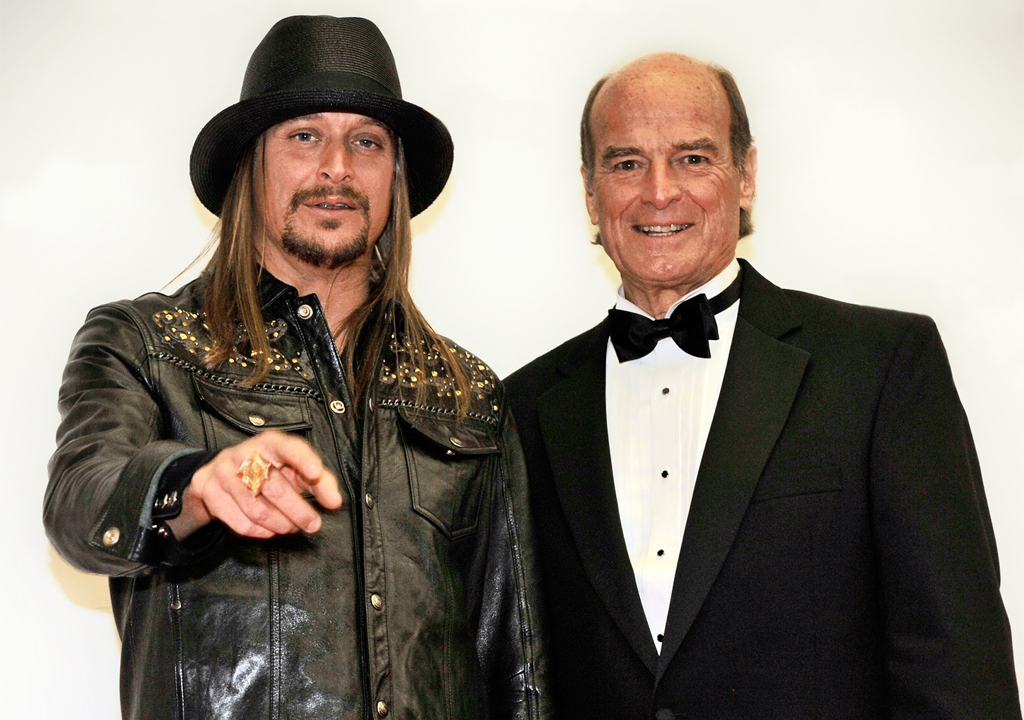

Kid Rock is so respectable in America now that Mitt Romney, the Detroit-born 2012 Republican presidential candidate, spent an hour pleading successfully with the star to endorse him. Sharing the Republican horror at people depending on welfare, Kid Rock’s eyes squint at the thought as he becomes tense with emotion for the only time in the interview. But when he muses about his beloved Detroit’s potential for recovery from within its black community, he is carefully, fluently thoughtful in a way a million miles from Bawitdaba.

A Detroit Pistons basketball shirt is framed on the wall, thanking Kid Rock for charitable work. In fact the one-time Devil is almost a statesman these days. Even in his most apparently fucked-up days, he admits, he always had this other side. His then young son “kept me alive” in the 90s, when he’d rarely tour and go wild for more than a weekend. The gap between his party-hard persona and his reality now seems even wider.

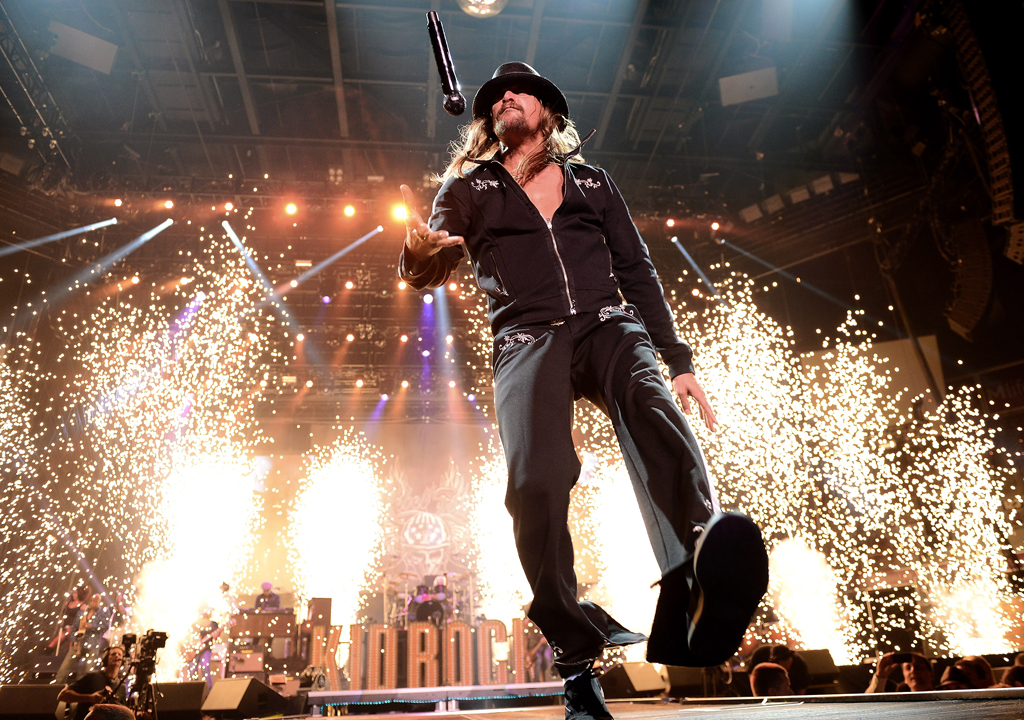

“But that big gap’s filled with a lot of other things,” he admits. “Helping the people around me, and family. You know, I still like to get after it. I don’t think that’s ever going to change. And when I get on that stage, you’ll still see that guy you’re talking about. But I’ve always been a tightrope walker – lean a little this way, a little that…”

A song on First Kiss called _Jesus And Bocephus _(the latter Hank Williams’s nickname for his son Hank Jr) wrestles with Kid Rock’s two sides.

“‘Jim Beam to my bible,’” he ponders, quoting the song’s lyric. “I feel like both those persons. I have the angel here and the devil here. The problem’s always been this motherfucker [the angel] never says anything!” he chuckles, “and this motherfucker’s saying: ‘Come on, man, let’s fucking go!’ I’ve been wild but I’ve never harmed people. In times of darkness, things are sad and bad, but I never felt I was that extreme one way or the other. I’ve had the most fun out of everybody, I’ve been the wildest of everybody, I’ve helped a lot of people. It’s all there for the taking.”

First Kiss is out on February 23 on Atlantic.

Nick Hasted writes about film, music, books and comics for Classic Rock, The Independent, Uncut, Jazzwise and The Arts Desk. He has published three books: The Dark Story of Eminem (2002), You Really Got Me: The Story of The Kinks (2011), and Jack White: How He Built An Empire From The Blues (2016).