Kate Bush: the long road to Hounds Of Love and the hunt for perfection

Kate Bush’s early years established her as the first lady of Brit rock, but after just one tour she retired from the stage. She wouldn't return for 35 years

Even by the seismic standards of the seventies, 1978 was a pivotal year. Punk’s revolutionary impact had translated into global success as The Clash and Blondie scaled the charts in the UK, while the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack was No.1 for months on both sides of the Atlantic, cementing disco as a world movement.

As editor of monthly punk fanzine Zigzag during this period, I was relentlessly bombarded by new records. Some were cutting-edge, most were derivative dreck.

One particular seven-inch single that arrived from the EMI Records press office a few days before Christmas 1977 was most definitely in the former category. Titled Wuthering Heights, it sounded like nothing else around; operatic, other-worldly and bathed in atmospheric magic.

The eye-catching cover image featured an exotically beautiful black-haired girl wrapped in just a scarf, hanging on to a kite. Her name was Kate Bush. And, although nobody could have known it at the time, the unknown singer-songwriter was about to become one of the most influential, successful and enigmatic female artists The UK has ever produced.

More than 40 years after that unique calling card, Kate Bush occupies a singular position in the world – one that allows her to do what she wants, when she wants, whether that’s leaving a 12-year gap between albums or a 35-year one between live shows. The sense of mystery that surrounds her has only grown with time, as has the devotion of her fans.

In 2014 she sold out 22 nights at the old Hammersmith Odeon in minutes is testament to her rare status and her ability to surprise. The news of those shows – which marked her first proper live appearances since 1979’s Tour Of Life – eclipsed even the return of David Bowie in terms of unlikelihood.

Watching the fuss surrounding Bush’s surprise return prompts a smile but little real shock in long-time observers and confidantes. I spent time with the singer in the early 80s, during what was a stormy, transitional period in her career. That was the point where she found her artistic feet and proceeded to put them down with a resounding thump, letting both her record company and the public know that, after an auspicious entry and exhausting stretch toeing the music business line, everything she did from here on would be on her own terms in her own time.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

I interviewed her three times over five years: for 1980’s career-affirming Never For Ever; for 1982’s audacious The Dreaming; and for 1985’s world-winning Hounds Of Love. As I was editing Zigzag – still a dispatch from punk’s front line but willing to cover anything radical and different – she had to be convinced my intentions were honourable and I wasn’t going to take the piss.

Enticed by her defiantly individual stance, I wanted to find out what made her tick and present her in a different light from the usual boyfriend speculation and digging for headline-friendly ‘weirdness’. She felt her potential audience was being restricted by the way the media had portrayed her, and decided, as she told me, that “it’s really good for me to speak to other magazines”.

She was, as has been said so many times, naturally friendly and innocently bewitching as she chatted about anything and everything in her sweet South London accent, displaying a maturity way beyond her 21 years. We hit it off over a mutual love of Captain Beefheart (“He’s not mad at all, it’s perfectly real,” she said), and this interview-room relationship blossomed over the next five years.

These marathon conversations, which Kate described as “like two psychiatrists talking”, revealed a young woman in total control of a destiny which seemed to unfold like a yellow brick road in front of her, to be skipped on when and how she pleased. Each time, she seemed to decide aloud there and then to record a new album instead of touring again.

Punk’s liberating energy had gripped Kate too by 1978, as she voiced support for the loud trail it had blazed through the weak, bland formulas dominating music. “Punk has actually done a lot for me in England,” she declared in US magazine Trouser Press. “People were waiting for something new to come out; something with feeling. If you’ve got something to tell people, you should lay it on them.”

She picked up that theme at our first meeting, in 1980, declaring her artistic independence and her life’s mission from here on. “It’s so bloody easy to be forgotten. It’s so easy to go under unless you fight. Everyone has to fight, and there are different ways of fighting. I’m definitely trying to state my presence. I must be. It’s important for me to do things on a one-man basis.

"I seem to work, produce, create better as one entity, and then I involve others for feedback. That seems to be the ideal way for me to work. You see, musically, too, I feel I’ve only just begun. I’m not doing what I want to do musically yet. I’m getting there, but it’s nowhere near to what I actually want.”

Kate Bush seemed to arrive fully formed with Wuthering Heights, but the story of the 19 years before that game-changing hit single is even more remarkable and unique: a pre-internet fantasy driven by precocious raw talent, nurtured the right way with a rare kind of upbringing and determination to do things her way.

On one hand, her upbringing could be viewed as being that of a privileged prodigy. Born in Bexleyheath, south-east London on July 30, 1958, she grew up in a 350-year-old farm in Welling, Kent, the Bush family home since the 50s. The wood-beamed farmhouse provided a maze of private spaces where the young Kate and her two elder brothers, John and Paddy, could explore anything from the literature in the library and the grand piano in the front room, to the old barn where she conducted her first musical forays on a rotting harmonium.

Although she didn’t have to get a Saturday job, she worked hard to achieve the personal goals she set herself, encouraged by her doctor dad. She wasn’t a carefree child; she thought deeply about everything, channelling her inner turbulence into poems and, later, songs.

“I had such an excess of emotion that I needed to get it out of my system and writing was how I did it,” she told me. “I think everyone is emotional, and I think a lot of people are afraid of being so, they feel that it’s vulnerable. Myself, I feel that it’s the key to everything, and that the more you can find out about your emotions the better.”

The house was the ideal incubator for her talents. Rather than going out to play with other kids, she stayed inside to practise the piano. She absorbed the influences that surrounded her, from classic British children’s books such as Peter Pan and The Wind In The Willows to Greek mythology (both of which would inform her songs). Irish traditional folk music was a constant soundtrack, while brother Paddy was always tinkering with his array of exotic instruments.

She listened to Simon & Garfunkel before graduating to Elton John, Roxy Music and David Bowie, laced with King Crimson and Billie Holiday. She loved the Incredible String Band, and the surreal blues guitar excursions of John Fahey; she was sufficiently moved to write a poem about the American Primitive guitar titan for her school magazine when she was 13, amid her usual narratives on religion and death.

While Bush hated the violin lessons enforced at school, she fed voraciously on influences including the literary giants she learned about from brother John, paganism, Buddhism, Eastern teachings, astrology and reincarnation.

At the same time, she loved TV, particularly Ealing comedies, Monty Python, musicals and horror films, and devoured sci-fi novelists such as Kurt Vonnegut and John Wyndham along with Oscar Wilde and James Joyce. She once confessed to me her love of Benny Hill and veteran cornball comic actor Will Hay.

In this most open of households, her earliest explorations were encouraged. By 13 she had already set her poems – including The Saxophone Song and The Man With The Child In His Eyes – to primitive piano chords. “I could sing in key but there was nothing there,” she told Trouser Press. “It was awful noise, it was really something terrible. My tunes were more morbid and more negative… they were too heavy.”

By the following year she had recorded several cassettes’ worth of demos and song sketches on her dad’s Akai reel-to-reel tape machine. Impressed, her family enlisted Ricky Hopper, a record plugger friend of John Bush’s, to hawk them around the labels in the hope of getting a publishing deal.

After all the majors had turned them down as “uncommercial”, Hopper contacted his old Cambridge University buddy David Gilmour. The Pink Floyd guitarist was sufficiently impressed to invite Kate to record a demo at his Essex home studio, backed by him and the rhythm section from Unicorn, a band he was also nurturing. “I was convinced from the beginning that this girl had remarkable talent,” Gilmour later said.

After that didn’t work either, Gilmour decided the only way forward would be to record three properly arranged songs. Putting up the money himself, he booked time at London’s AIR Studios in June 1975, bringing in arranger friend Andrew Powell, who had worked with Cockney Rebel, Pilot and Alan Parsons. They recorded The Saxophone Song, The Man With The Child In His Eyes and Maybe, with members of the London Symphony Orchestra (the first two songs would appear on her debut album, The Kick Inside).

Gilmour played the demo to Bob Mercer, then head of EMI’s pop division, who was impressed enough to sign her up. A deal was eventually sealed by July 1976. Having left school with 10 ‘O’ Levels, Bush set up a company to manage her affairs – a precocious glimpse of the total control that would come later in her career.

EMI were willing to give the young singer time to craft her songwriting and performance. Ever the maverick, she began to study with Lindsey Kemp, the provocative mime artist who had been a mentor to the young David Bowie. Under Kemp’s tutelage she began to imbue her music with character and movement – magic extra ingredients in her presentation.

At the same time, she was willing to play along with the more traditional elements of the rock’n’roll to hone her stagecraft. She put together the KT Bush Band – future boyfriend and lifelong collaborator Del Palmer on bass, guitarist Brian Bath and drummer Vic King – with a view to playing live. Belting out Beatles, Stones, Free and Motown classics, as well as such Bush originals as Them Heavy People and The Saxophone Song, in London pubs and clubs for 20 quid a night, it was her first experience of singing on a stage.

While there were typically thankless gigs, the band’s residency at the Rose Of Lee pub in Lewisham between April and June 1977 became rammed after a few weeks. Sporting long robes, she worked on her dance moves, donning a cowgirl outfit and brandishing a toy pistol for James And The Cold Gun.

Kate’s rock-chick stint finished when EMI finally called her in to record her debut album. She had been building to this moment for years, having already honed the songs. At first, she had to fight against being typecast by the record company as a bland, piano-plinking female albums artist. But from the off the quietly assured Kate was painstakingly building her skyscrapers of vocal overdubs.

The Kick Inside was recorded at AIR studios over six weeks in July and August 1977. The KT Bush Band naturally thought they’d be backing their recent singer, but producer Andrew Powell brought in musicians he’d worked with, including bassist David Paton and guitarist Ian Bairnson from Pilot (who’d hit No.1 in 1975 with January), plus drummer Stuart Elliott and keyboard player Duncan MacKay from Steve Harley’s Cockney Rebel.

At this stage, Bush allowed herself to be guided, even ordered, by the experienced Powell, seeing it as part of her ongoing learning process. It was as if every experience, even ones she wasn’t happy with, was essential, if only to tell her what not to do. Like Mick Jones of The Clash diligently soaking up Sandy Pearlman’s laborious realisation of his group’s second album so he could co-produce their masterpiece London Calling, Bush watched Powell work, absorbing the ropes to use when she struck out on her own a couple of years later.

Although underpinned by conventional song structures and of-its-time muso embroidery, the album, The Kick Inside, boasted enough of her personality and vision to set it apart. Inspired by a traditional ballad, the title track concerned an incestuous relationship between brother and sister, sung before the pregnant girl commits suicide.

Them Heavy People name-checked Greek-Armenian Sufi mystic Gurdjieff, among other teachers. L’Amour Looks Something Like You revealed her astonishingly mature attitude to sex in a smoky haze. While rock often dealt with the subject at the most basic levels of fumbling macho trouser trumpeting, Bush was already exploring the sensual world with intoxicatingly descriptive powers – much of the album dealt with her own sexual awakening. This was new ground for female singer-songwriters, which wouldn’t really be appreciated until the fuss over her more obvious traits had died down.

There was also that single. Inspired by the last 10 minutes of the 1970 film adaptation rather than the Emily Brontë novel, Wuthering Heights, was written on full moon a few days before recording started. Placing herself as Catherine’s ghost outside in the cold, the ‘It’s me, Cathy’ line made a perfect introduction. But EMI wanted the more conventional James And The Cold Gun as first single. Bush put her foot down and got her wish. Which was unusual at the time, as artists were routinely overruled by record companies, but indicative of the quiet strength Bush could summon to get her way and steer herself the way she planned it.

Released on January 20, 1978, the song crept into the Top 50, bolstered by a Top Of The Pops appearance that she later described as “like watching myself die”, before it claimed the top spot and Bush became the first British female artist to have a self-written UK No.1 hit. But now the hard work was about to begin.

With a No.1 single in her pocket, Bush was plunged into months of punishing promo: TV shows, showcases, interviews… Her second single, the ethereal The Man With The Child In His Eyes, was released in May. Foreshadowing what was to come, she went head-to-head with EMI, who favoured Them Heavy People. Bush won.

But there was a downside. Caught up in a whirlwind of success, she missed her friends, family and home stability. If that wasn’t bad enough, she also didn’t have time to plug into her ever-swelling muse and write any new songs. Faced with having to come up with a new album in four weeks, she could write only three songs, reaching into her stockpile of old ones for the rest. By July she was holed up in Superbear studios in the South of France, recording the 10 tracks which would become her second album, Lionheart.

Looking for a bigger wallop in the sound, she was allowed to bring the KT Bush Band back, but clashed with Powell, who wanted to use his musicians again. At one point, two sets of players were making the same album for an artist seeking a greater level of control herself. Powell’s crew eventually got the company nod, with the KT Bush Band playing on just two tracks. Bush had to bite her lip to deal with what Powell later called her taste of “second-album syndrome”. It became another life-defining experience never to be repeated.

The first single, Hammer Horror, stalled at 44, while the album reached No.6 when it was released in November. Bush was unhappy with having been rushed into making the Lionheart record, and was determined to make sure it wouldn’t happen again.

“It’s a big trap for a lot of artists because they’re normally very sensitive people, maybe slightly neurotic,” she told me in 1980. “That’s why they write, because there are things they have to get out. Normally what goes along with that make-up in a person is this neurosis, this insecurity, and it’s inevitable that someone who is like that, when they’re put in a situation where there’s pressure, things they can’t actually see as a reality, are going to crack. They find the pressure is too much. They lose themselves and everything they have. And that’s very sad.

“I don’t intend to let pressures of success make me go under and lose everything I have. Pressures of life, yes, I think that’s something that can happen to anyone. There’s nothing you can do about it except to try to be as strong as you can.

"Pressures of success are so meaningless anyway. Success is a label other people like to put on you so they can go ‘Success!’ I don’t feel successful. There’s so much that I have to do to feel that I’ve really done what I want to. My success is in terms of fulfilment of my art, perfection of my art. That’s something I’ll never reach. I never will. And I have to accept that.”

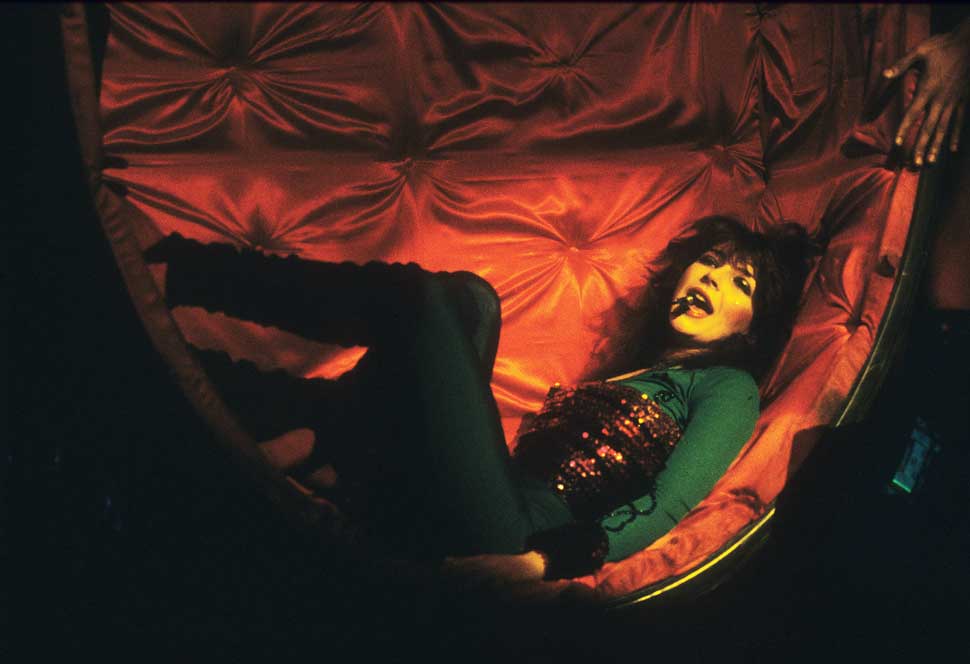

If the Lionheart experience had a positive aspect, then it was a galvanising element on her one and only tour. Opening in Liverpool on April 3, 1979 the retrospectively-named Tour Of Life was the logical culmination of her interest in music, dance and theatre. Her only tour to date, the groundbreaking production saw Bush living out her songs with dancers and mime-magician Simon Drake.

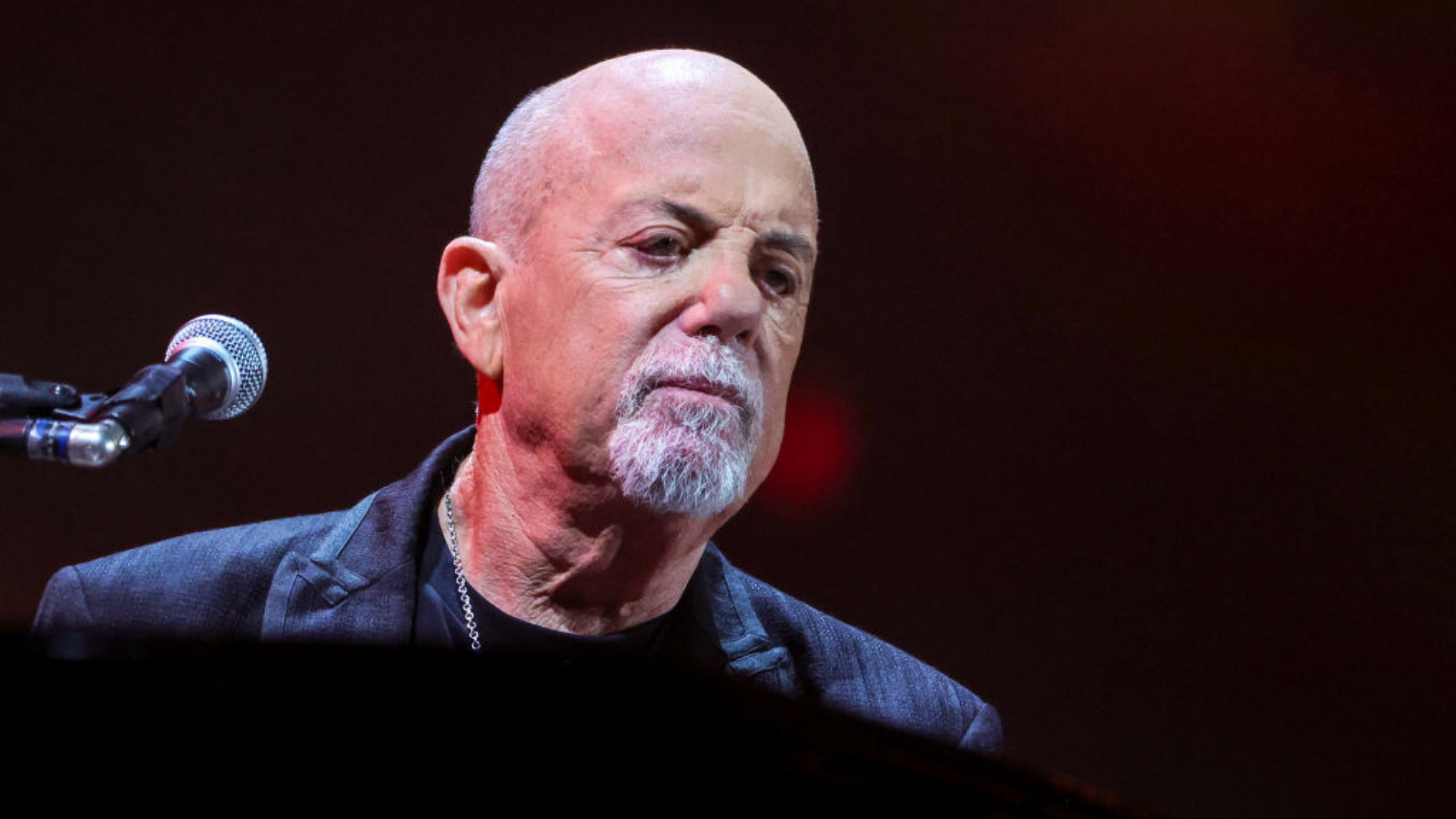

I caught the tour twice at London’s Palladium. The first night I escorted Siouxsie Sioux, who wanted to check out the competition, but our tickets had been swiped so we were uncomfortably reseated in the gods. So I went again, and sat a few rows from the front. I was as close to a theatrical production as popular music has ever got; only Bowie’s legendary show at the Rainbow or his Diamond Dogs tour two years later are comparable.

As with Bowie, Bush’s songs became pieces performed with props and sets, accommodating cinema and burlesque. She often sported a pioneering head-microphone. Her 17 costume changes included magician’s assistant, gunslinger, Grease-style rocker and ghostly apparition, linked by brother John’s booming poetry.

Beginning with Moving, Kate appeared in front of a large, egg-shaped screen (complete with flap for her to emerge from) on to which various seascapes, deserts and clouds were projected. She covered both her albums, even trailered the next with Egypt (in Cleopatra gear), and Violin complete with violin suits.

In the spirit of theatrical production, there were no announcements, but the solo ballads at the piano were mesmerising. The main show climaxed with a space cowboy shoot-out on James And The Cold Gun, the first encore was Oh England, My Lionheart presented like a World War II film with Kate in an air helmet and leather jacket, followed by Wuthering Heights before the stage curtains closed.

Three final shows were added at Hammersmith Odeon in May, including a benefit for the family of stage lighting worker Bill Duffield, who had suffered a fatal fall on the opening preview night in Poole. Bush was joined at Hammersmith by Peter Gabriel and Steve Harley, who all swapped songs.

“You didn’t take a dancer or magician on stage. You might have used those tricks and props in videos, but even Queen or Floyd at their most extravagant didn’t have other people on stage,” says Brian Southall, the head of press at EMI when Bush was signed.

“It was a constructed, choreographed show. Those songs were performed, rather than just played, which was the extraordinary thing about it. She was only going to go on tour in the way she wanted to go on tour. It was an expensive, extravagant event. She wasn’t prepared to play the conventional thing. Kate was very determined about how her music was presented and performed. That was pretty obvious from the first album. She was very independent and determined to do things her own way.”

She was also determined not to repeat the draining experience of touring. Despite offers of a prestigious showcase at New York’s Radio City Music Hall and a support slot on Fleetwood Mac’s enormous Tusk tour, after those final Hammersmith shows Bush, to all intents and purposes, retired from playing live for 35 years.

Having played the record company game on the first two albums and proved she could raise the bar with touring, Bush determinedly took the production reins for 1980’s Never For Ever, the first album where she felt she started taking charge of the creative process.

There were still battles to be fought: EMI wanted the jaunty Babooshka as first single, but Bush insisted on the epic Breathing, her most experimentally ambitious song to date, sung as a post-holocaust foetus reluctant to enter the scorched world. Then came Babooshka and the anti-war Army Dreamers.

In summer 1980 Bush was successfully emerging from the disappointment of Lionheart. When we met at EMI’s Manchester Square HQ, the execs were in another room toasting Never For Ever entering the album chart at No.1.

“I still can’t believe it,” Kate gleamed, before subtly dismissing the first two albums and proudly asserting her brave new direction. “I couldn’t have asked more for such an important step in what I’m doing, because I feel that this album is a new step for me. The other two albums are so far away that they’re not true. They really aren’t me any more. I think this is something the public could try to open up about. When you stereotype artists you always expect a certain kind of sound.

“When you first come out, people say you’re the new thing. Then when you’ve been around for two or three years you become old hat and they want to sweep you under the carpet as being MOR, which I don’t feel I am from the artistic point of view. It doesn’t feel like MOR to me at all, although I wouldn’t call it punk! Sometimes it’s not even rock…

"I don’t know, I think it’s wrong to put labels on music. Even ‘punk’ covers so many areas. I think sometimes it can actually kill people, being put under labels. I think it’s something that shouldn’t be encouraged. If people could just accept music as music and people as people, without having to compare them to other things… which is something we instinctively try to do.”

She’d moved on further when we met two years later to talk about her fourth album, The Dreaming, which saw her painstakingly expanding her studio visions using new technology, confessing that selling records was now a minor concern.

“I find the more I write the stuff, the less I worry about this stage, and the better it is,” she revealed. “I remember on the second and third albums there were lots of times when I was writing a song and I kept thinking what people were going to think of it. I’d rather not do that and lose some of the people who are into my music, because I’m really doing what I want to do. I’m going where I want and I’m going to keep going for it. I’ve no idea what’s going to happen.”

What happened next was that Kate Bush seized total control of her career. Her 1985 album Hounds Of Love was the work of a true auteur, one with a clear vision of who they are and what they want to make. The gaps between albums became increasingly long as she focused on the studio and family life with her partner, Dan McIntosh: four years between Hounds Of Love and The Sensual World, another four between that and The Red Shoes, then a staggering 12 years until Aerial (in fairness, she released two albums in 2011).

If she pulled away from the treadmill of releasing and promoting records, then she virtually disappeared from live appearances, aside from a handful of fleeting guest appearances with other artists, notably in 2002 with David Gilmour at the Royal Festival Hall when she duetted with him on Pink Floyd’s Comfortably Numb.

All that changed in 2014, when she announced the string of shows at Hammersmith Apollo, dubbed Before The Dawn (tellingly, it was a super-charged residency rather than a tour). Three decades of wondering when she’d return to the live arena gave way to wondering exactly what she’d do now that she had.

“I always thought she’d have to come out of her shell again in the end,” said early champion Steve Harley. “Will she have magicians or illusionists with her or not? I wouldn’t care. Two hours of her sitting at the piano with a guitar player would be fine.”

Indeed it would. But it was so much more.

Kris Needs is a British journalist and author, known for writings on music from the 1970s onwards. Previously secretary of the Mott The Hoople fan club, he became editor of ZigZag in 1977 and has written biographies of stars including Primal Scream, Joe Strummer and Keith Richards. He's also written for MOJO, Record Collector, Classic Rock, Prog, Electronic Sound, Vive Le Rock and Shindig!