"A ninth album would have been about riffs - interestingly constructed riffs and hypnotic music": Jimmy Page looks back on the tests and turmoil of Led Zeppelin's final albums

The man who led Zeppelin looks back on Presence, In Through The Out Door and Coda

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

It was a time of upheaval and tragedy, yet Coda, In Through The Out Door and Presence showcase some of Led Zeppelin’s most intriguing work. In late 2014, as Jimmy Page put the finishing touches to the deluxe edition editions of those albums, he spoke with Classic Rock.

Whenever Jimmy Page is asked a question that he’s uncomfortable about answering, his body language betrays him. His shoulder twitches and his lips purse. He will answer, although not necessarily the question you asked. It’s a game. And a game that Jimmy Page is an old hand at.

Led Zeppelin’s guitarist/producer/gatekeeper has been on the campaign trail since March 2014. Since then, each Zeppelin album has been remastered and reissued under Page’s watchful eye. For seasoned Zeppelin followers, it’s been like having several Christmases in a year. For Jimmy Page, it’s meant answering – and sometimes dodging – questions about Robert Plant’s solo career, groupies, drugs and Satan. There’s been a lot of shoulder-twitching and lip-pursing these past 16 months.

Now, though, Page’s work is done. This month sees the release of the final three: 1976’s Presence, 1979’s In Through The Out Door and 1982’s out-takes collection, Coda. But for Page, will it ever really be done?

We meet on a Friday afternoon in West London in what was once Olympic Studios and is now a private members’ club. Page is wearing regulation black and a raffish scarf, and looking eerily healthy for a septuagenarian rumoured to have spent years gone by in a pharmaceutical haze.

Earlier, he hosted a playback of tracks from the new reissues. The club’s impeccable sound system pumped new life into every note and nuance. Tell Page this, and the inscrutable gaze softens and the eyes light up. The problem is, we’re here to talk about Coda, but also Zeppelin’s final album, In Through The Out Door.

Previously, Page has described it as “too polished” and “not really us”, though Zeppelin’s worst is better than some groups at their best. Perhaps it’s not helped by the fact that it came after the guitar-heavy Presence, rumoured to be Page’s personal favourite. Either way, let the twitching and lip-pursing begin.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Is Presence really your favourite Led Zeppelin album?

I certainly really like it. It’s a bit of a muso’s album, though, isn’t it? So many times, I speak to people and they say that Presence is their favourite, and it always surprises me, because you’ve got to really listen to what’s going on.

It wasn’t made under the easiest of circumstances, was it?

No. Robert had had his accident [a car crash in Rhodes in August ’75], so his leg was in plaster in the studio. So that was a set of circumstances right there that wasn’t in script. So Presence was very reflective of what was going on – a lot of darkness and intensity. There’s some extraordinary stuff on there: from my point of view, Achilles Last Stand, but also Tea For One, where Robert is singing his heart out.

When Led Zeppelin played the Presence track For Your Life at the O2 reunion, could you see that some of the audience didn’t know it.

Yes, I could. Some reviewers even wrote it was a new song [looks appalled]. Mind you, perhaps that shows how popular Presence is in the grand scheme of things! [Laughs]

On the deluxe edition there’s a piano ballad called Pod. But it feels like the beginning of In Through The Out Door rather than part of Presence.

Yes. It wasn’t going to go on Presence because Presence was a guitar album. But [bassist] John Paul Jones presented this piece, and it says something that in among all that intensity and darkness we could do something like this. It was good enough for In Through The Out Door, but by then we’d done a new set of writing.

Before Led Zeppelin started In Through The Out Door, they had to survive 1977. On July 24, they played what turned out to be their final US gig at San Francisco’s Oakland Coliseum. All the darkness and intensity of Presence reached fever pitch, when drummer John Bonham helped beat up a security guard backstage. Worse was to come. A day later, Robert Plant learned that his young son, Karac, had died from a viral infection at home in the UK. “It was a terrible time, God, yes,” sighs Page.

And one that led to Plant walking away from Led Zeppelin. When he returned, he was keen for the band to do something different in the studio, “something more conscientious and less animal”, he said later.

Plant wasn’t the only one with new ideas. When Zeppelin reconvened in May 1978 at Clearwell Castle, in the Forest Of Dean, John Paul Jones unveiled his new toy, a Yamaha GX-1 keyboard. “Stevie Wonder had one,” says Page, “We called it The Dream Machine. Immediately, John Paul started writing full numbers on it.”

Plant and Jones’s new ideas and instruments would have a major impact when Zeppelin arrived at ABBA’s Polar Studios, in Stockholm, to start work on their next album.

How did Led Zeppelin end up recording in ABBA’s studio?

They contacted me. The studio was only known for ABBA and they wanted an internationally known rock group to record there, and would Led Zeppelin consider it. We had a chat and they said they’d be generous with studio time. We went out there in December [’78], I think. It was biting cold, snow everywhere…

Did you meet ABBA?

I met Björn [Ulvaeus] when I was setting up. I don’t think the others had got there then. He gave me a guitar, which was very sweet. A day later I met Benny [Andersson]. Björn was the blond one? Benny was the one with the beard and the keyboard, yes? [Laughs] He was very interested in John Paul’s new toy. At the time Benny was still married to Frida [Lyngstad]. So we all went out to a club together one night. They were nice people.

You didn’t meet Agnetha [Fältskog] then?

No, I was rather hoping we were going to meet Agnetha, but that wasn’t part of the deal!

Revisiting the album again, what was the first thing you noticed about it?

The album sounds a little bit contained. It was a state-of-the-art studio, but there was no ambience. We had to take the front bass skin off John Bonham’s drums. Then we had to use a machine to create a fake ambience.

How was the mood in the band at that time?

It was good, as far as I knew.

Robert Plant has said that his lyrics to Carouselambra (‘And powerless the fabled sat/Too smug to lift a hand…’) are about the tension in the band at the time. Did you know that?

I’m sure they were… but I didn’t know. The way we listened to music then was to make your own interpretation. We were still a few years away from videos where they told you what the song was about. In the early stages of Led Zeppelin I wrote lyrics. But if I’d concentrated on lyrics I wouldn’t have been able to give as much attention to the guitars.

John Paul Jones remembered the Polar sessions like so: “The band was splitting between people who could turn up at recording sessions on time and people who couldn’t,” he told Zeppelin biographer Barney Hoskyns in 2012.

Those who couldn’t were Bonham and Page, both of whom were supposedly using heroin. Ask Page about his drug use and he clams up, every time. He doesn’t deny it, but insists that, whatever else he was doing at the time, he was always ready to work.

“When I needed to be focused, I was really focused,” he said. “Presence and In Through The Out Door were only recorded in three weeks. That’s really going some. You’ve got to be on top of it.”

But although he produced the album, as usual, In Through The Out Door is the only Zeppelin release to include original songs not written or co‑written by Page. After seven studio albums in which his iron grip on Led Zeppelin never weakened, you can’t help wondering why it did so at the end.

In Through The Out Door is very much the Plant/Jones album. The impression is that they were in a huddle together while you were otherwise engaged.

[Long pause]. Hmm… I do remember them being in a huddle, yes. That was good, though, wasn’t it? I had done a serious amount of writing all the way through and having done all the writing on Presence, I was relieved. Okay, Robert and John Paul are writing numbers together? Let them do it. Cool. I was very happy about it.

Really?

Yes, really, because I had just done a whole guitar album.

In Through The Out Door is quite a lightweight album. Fool In The Rain and All My Love are very poppy. What did you think of those songs?

I think they’re good. They’re alright. It was another dimension. On Presence, I wanted to do something that made a show of the guitars. That’s why Achilles Last Stand was a guitar orchestra extraordinaire. But with Fool In The Rain, even with the chorus and the acoustic guitars, when it comes to the solo, I employed a sound that made people go, “What the hell was that?” – even on a keyboard album. It made you think.

Were you aware that All My Love was about Robert’s son Karac?

Yes. I realised that it was over time.

Let’s pick a track at random: the piano number, South Bound Suarez. What do you remember about that?

I remember everything. I honestly do. What do you wanna know? Yeah, it’s a piano number, and I played a [B-] string-bender on the chorus [long pause]. Look, it was a departure…. The thing with In Through The Out Door is that there’s nothing like an Achilles… or a Kashmir on there.

In The Evening comes close, though?

In The Evening is maybe in that sort of vein. People always say that that’s the song on In Through The Out Door that feels closest to the Led Zeppelin they know. And my solo on that is another one that makes you think, “What the hell?”

When Coda came out, a lot of fans wondered why that great track Wearing And Tearing hadn’t been on In Through The Out Door?

Because the album was so much lighter, it wouldn’t have fitted. Wearing And Tearing was ‘One, two, three, four, charge.’ My goodness! It was like an assault. It wasn’t in character with something like All My Love.

Do you think In Through The Out Door was just another progression? Like the one from Led Zeppelin II to III?

A logical progression, yes. But after In Through The Out Door, we would have done an album that was entirely different.

So what would the ninth Led Zeppelin album have sounded like?

[Emphatically] Riffs, interestingly constructed riffs and hypnotic music. John Bonham and I spoke about this a lot. Let’s put it this way, on the next Led Zeppelin album, John wouldn’t have been playing with brushes. John loved the idea of anything where he could really get going.

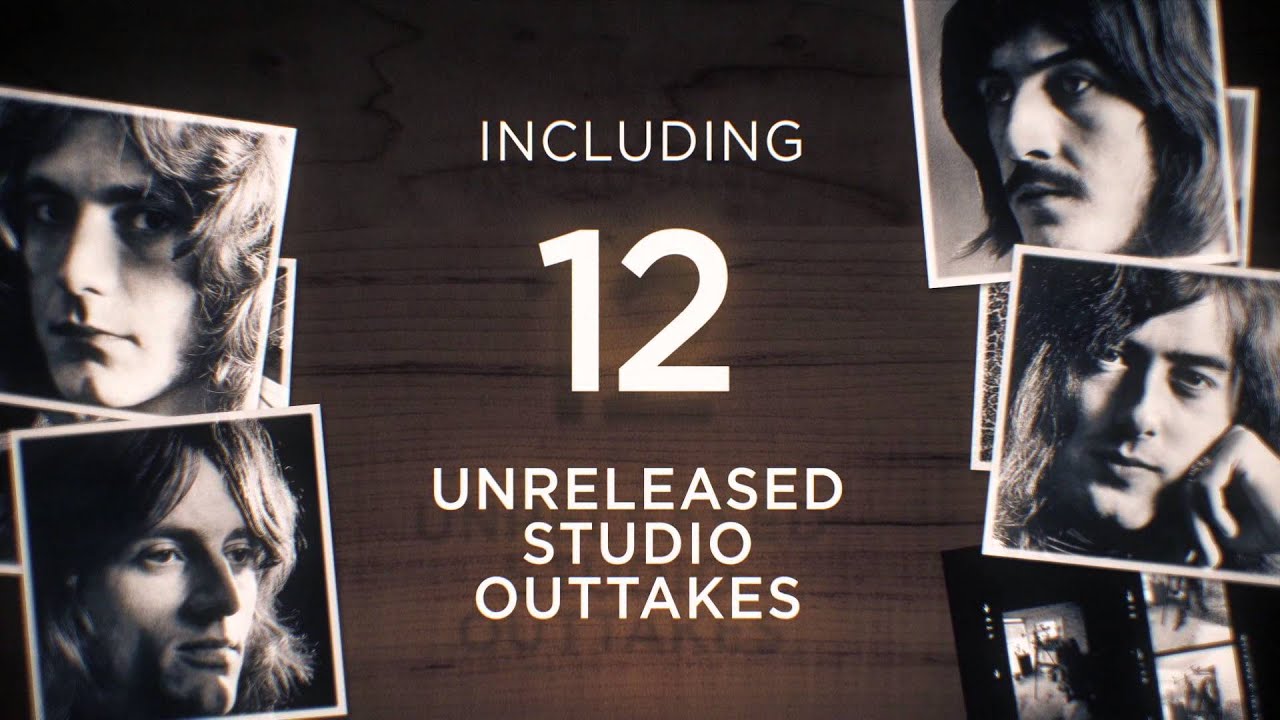

Led Zeppelin IX never happened. When John Bonham died on September 25, 1980, Zeppelin died with him. Two years later came Coda, an album of outtakes, including Bonham’s drum extravaganza, Bonzo’s Montreux. The deluxe version of Coda brings more buried treasure to light, such as Friends and Four Sticks (retitled Four Hands), recorded by Page and Plant with Indian musicians in 1972.

Listening to Page discussing this material, you glimpse the obsessiveness that helped make Led Zeppelin such a force, but also a reluctance to reveal too much, as if this will diminish his and/or the music’s power. You realise why Robert Plant once described his old bandmate as “a man of mystery… hiding in shadows and peeping round corners”.

Yet, you also glimpse a more innocent time – if ‘innocence’ and ‘Led Zeppelin’ could ever be used in the same sentence – before the so-called “darkness and intensity” took over. Most of all, though, you realise how much John Bonham’s death impacted on him.

Coda seemed to creep out in 1982. There was none of the fanfare that’s accompanied these latest reissues.

It was a very difficult album to approach. We’d lost John in 1980 but even when I came to do Coda, it still felt tough [long pause]. It was a contractual album. We had to do it.

How did you approach it?

It had to have credibility, because it could have been quite unpalatable otherwise. It helped that we had Darlene, Ozone Baby and Wearing And Tearing from the Polar Sessions. And only John and I knew about Bonzo’s Montreux.

Why didn’t the others know about it?

Because it was something we did together – just him and me. John was alone in Montreux at the time [Bonham was taking a tax year out of the UK in 1976], so I went there to cheer him up. John liked all those old Sandy Nelson records, because of the drums. So we wanted to make something that sounded like a drum orchestra. It was fun, but it wouldn’t have fitted on any of the albums.

So what were you aiming for with the new Coda?

To make the mother of all Codas! [Laughs] Before I started this whole campaign, I had to know what I was saving for this one – all the little treasures.

Let’s talk about Friends and Four Hands, then. We’ve read about the trip you and Robert took to India in ’72, but never heard the music you made there.

We were on the plane from Australia and had to break up the journey for refuelling. I had worked out a situation where we could go into a studio [EMI Studios in Bombay] with some Indian classically trained musicians. I wanted to see if it was possible to go in with a guitar and an interpreter and make something happen.

Had these musicians heard any of Led Zeppelin’s music before?

No. It was 1972 and they were immersed in their own world. But Friends was written around the idea of Indian music. I just about managed to explain it to them. On Four Sticks, they did things in odd times and multiple beats. As far as I was concerned, I was in paradise. I’d gone in to do something that seemed impossible and I’d done it.

You were an early fan of Indian music. You owned a sitar when you were a teenager, didn’t you?

Yes [long pause]. This story has leaked out… Now I suppose it will leak out even more. I managed to acquire a sitar, when I was a teenager, early on in my session musician days. I’m not saying I was the only person interested in Indian music, and I’m not detracting from George Harrison’s sitar work but I was in there earlier… Although I had to get Ravi Shankar to show me how to tune it.

How did that happen?

I had a connection with a lady that knew Ravi Shankar and said she’d get me an introduction. I went to see him when he played in London. There were members of the Indian high commission and Indian actors there, but no other young people. I was granted an audience with the master and he showed me how do it.

Will we ever hear Jimmy Page playing sitar?

I still have the sitar and I still play, but you don’t mess with two thousand years of culture. To hear Ravi playing, now that’s amazing. It’s a spiritual discipline.

Ten years ago you talked to me about making a solo album. What is happening with that?

Look at the reality. Ever since the release of [the Zeppelin reunion live DVD and CD] Celebration Day [in 2012] I’ve been working on this material, selecting and rejecting, to get to where we are today. This is Led Zeppelin’s reputation. But I’m happy that it’s all accomplished. Now I can concentrate on all things guitar.

Have you actually recorded some new music?

Yes, I’ve got new music. But I haven’t worked with other musicians on any of it. But never mind what I have or where it is – is it acoustic, electric or experimental. I’d rather be seen going out there and playing publicly rather than doing it at home.

This reissues campaign had been your life for the past couple of years – but only yours. Why aren’t Robert Plant and John Paul Jones sitting here as well?

I’ve not heard from them about this new stuff, but they know how things have shaped up. But we all know I formed the band and I was the producer, and consequently I have all the points of reference, more than anyone else. [Long pause] Some people might have forgotten all the things we did, but I didn’t forget. I’m the one who knew.

With the recording device switched off, the other Jimmy Page reappears, all easy grins and friendly chit-chat. “When we talk again about my new solo album, let’s see how confident I am then,” he jokes.

But can any new music Jimmy Page makes possibly measure up to Led Zeppelin, and also to his own exacting standards? And as the now 71-year-old leader of one of the biggest rock bands of all time, who’d blame him if he never played a another note? But Page is both Led Zeppelin’s number one authority and their biggest fan. He can’t let it go. Maybe that’s why he’s so defensive when discussing In Through The Out Door. The truth is – whisper it – it wasn’t as good as the other albums, and he knows it.

As a parting shot, I tell him that there are a lot of Zeppelin fans of a certain age for whom Zeppelin’s last album was their first; who vividly remember the LP coming out, hearing In The Evening being played on the radio, and as such have a soft spot for it. “Okay,” he says, looking slightly surprised. “I can understand that. Yeah, that does makes sense.”

As he leaves the room, you notice that his shoulders are finally down, the lips are un-pursed and once again Jimmy Page is smiling.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 213 (January 2015)

Mark Blake is a music journalist and author. His work has appeared in The Times and The Daily Telegraph, and the magazines Q, Mojo, Classic Rock, Music Week and Prog. He is the author of Pigs Might Fly: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd, Is This the Real Life: The Untold Story of Queen, Magnifico! The A–Z Of Queen, Peter Grant, The Story Of Rock's Greatest Manager and Pretend You're in a War: The Who & The Sixties.