“If you’re a Zep fan and really want to go see Zeppelin, you might as well go and see one of the better tribute bands”: The epic life and career of John Paul Jones, the heartbeat of Led Zeppelin and so much more

Crack session musician, in-demand producer, one quarter of the world’s biggest rock band – ex-Led Zeppelin bassist John Paul Jones has done it all

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

John Paul Jones is most famous for being the bassist and keyboard player in Led Zeppelin throughout their 12-year lifespan, but he had successful and fascinating career before and after as a session player, arranger and, later, producer. In 2010, he was playing bass alongside Dave Grohl and Josh Homme in Them Crooked Vultures and was the recipient of the Outstanding Achievement honour at that year’s Classic Rock awards – the perfect opportunity to sit down and look back over his stellar journey.

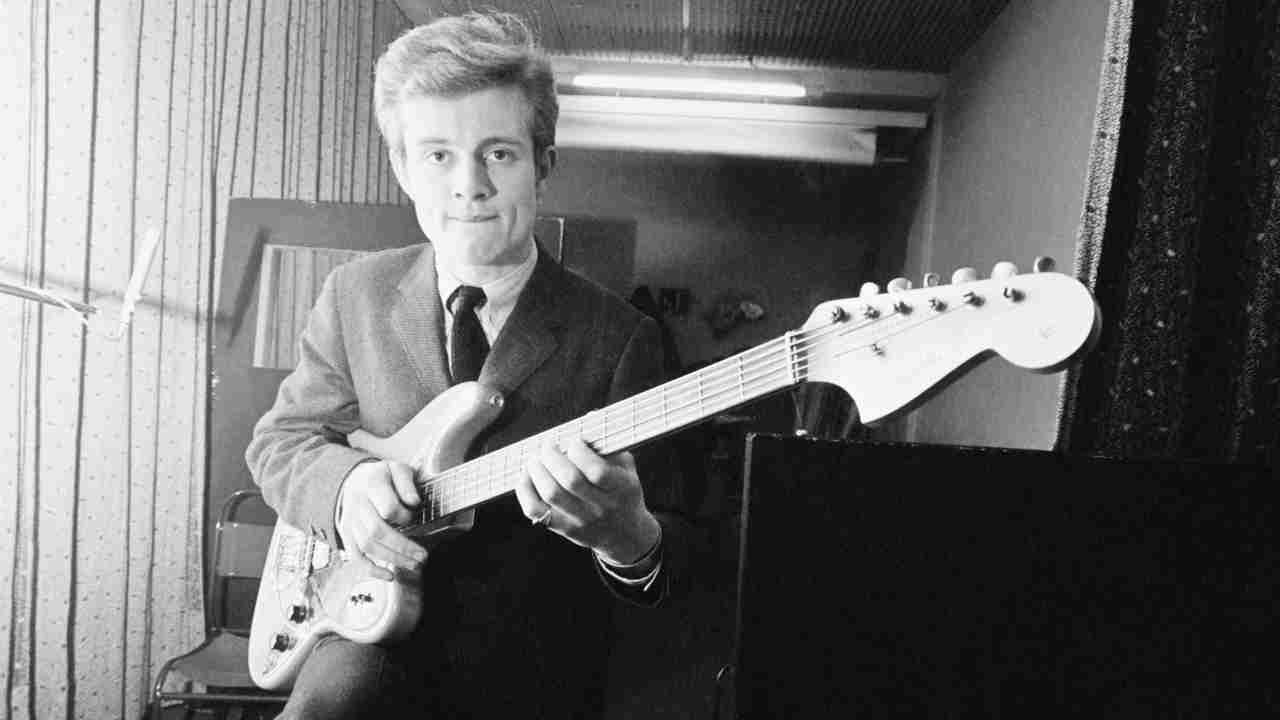

John Paul Jones seems quietly at ease with his standing as one of rock’s elder statesman. It’s exactly 50 years since he joined his father’s dance band, aged just 14, after which he began touring with The Shadows. From 1964 onwards, he played on and directed sessions for The Yardbirds, Donovan, Marc Bolan, Cat Stevens, Marianne Faithfull, Tom Jones, The Walker Brothers and many more. The Rolling Stones even brought him aboard for the string arrangement on She’s A Rainbow.

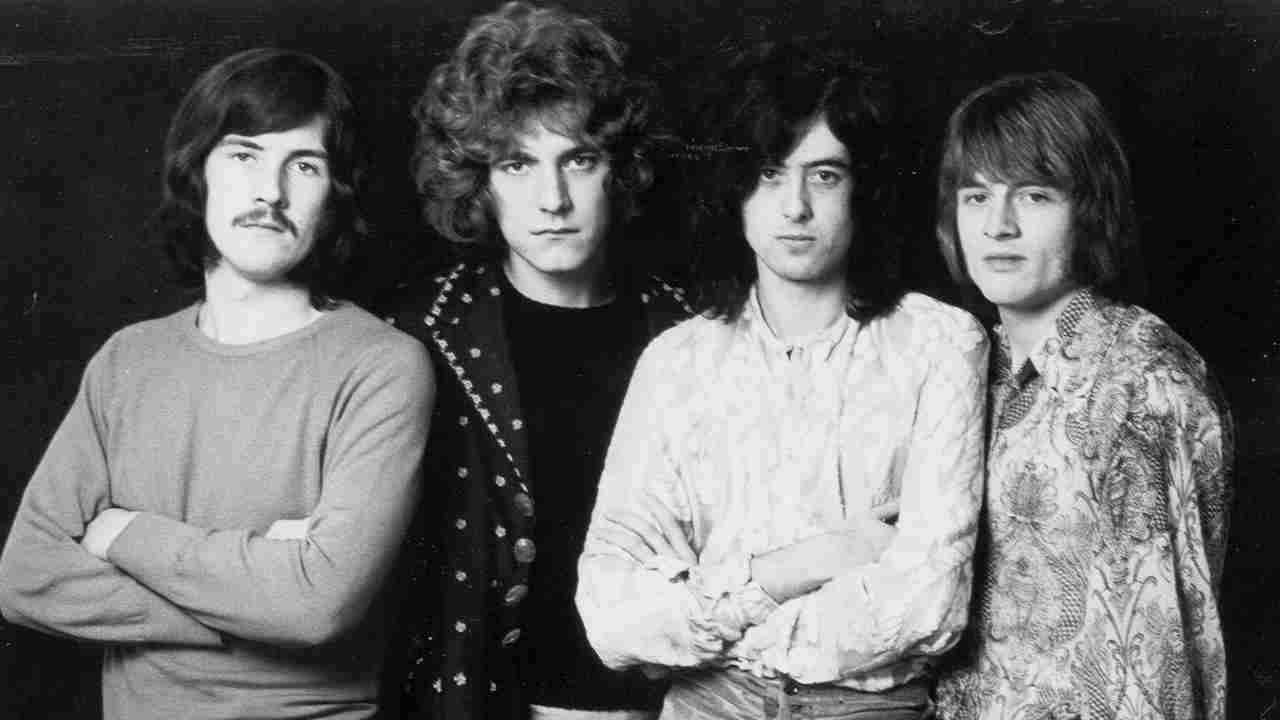

His seat at the high table of rock was secured, however, when he formed Led Zeppelin with Jimmy Page in 1968. Page may have been more flashy, Plant more God-like and Bonham more thunderous, but it was bass and keyboardist Jones who provided the band with its distinctive textures and mighty eclecticism.

Since then Jones has worked with a dizzying array of artists, including REM, Peter Gabriel, Ben E King, Butthole Surfers, Heart, The Datsuns and Sonic Youth. The past 18 months have seen him return to high-profile rock via membership of supergroup Them Crooked Vultures, alongside Dave Grohl and Josh Homme. Now 64, age has failed to dim either his resolve or his musicianship. “Getting older gives you more freedom,” he laughs. “People either assume you know what you’re doing, or else they just don’t care. So do what you like!”

You turned professional in 1962, then became session player, musical director and arranger for people like Andrew Loog Oldham and Mickey Most. So how did you get involved with them?

I used to stand on the corner of Archer Street in Soho every Monday, where all the musicians were at. Eventually I saw Jet Harris and asked him if he wanted a bass player. I’d seen him for a couple of weeks, but just couldn’t bring myself to ask. But when I did, he said: “I don’t need anyone, but they do.” And he pointed to the band he’d just left, which was [jazz-rock combo] the Jett Blacks. I went to audition for them, but Jet heard the audition too. This was when he was just starting The Shadows with Tony Meehan and he said: “No, you’re coming with us!” So I never got to actually play with the Jett Blacks. I was just 17 at that point. Suddenly the whole thing happened for me.

Then I started doing a lot of sessions and watching a lot of arrangers, picking it up as I went along. When somebody asked if I could arrange, I said: “Yeah, of course.” My Dad once told me: “Never turn down work.” And I didn’t. So I went out and bought a book, which taught you how to orchestrate. Forsyth’s Orchestration, it was called. The thing to remember is that, in those days, sessions weren’t like they are today. We’d do two or three a day, for a start, and you didn’t usually know who you were going to be playing with until you actually saw them. Back then they used to do the vocals at the same time. So you’d be standing in a little box and you could see them through the glass.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

There’s a myth that musicians of today aren’t as adept as those of your era.

It’s just not true though. It’s like saying that people aren’t as adept because they use samplers or turntables. People say, “Oh, they’re not real musicians.” Oh yeah? Well, here’s a turntable and a sampler – go and make a fucking killer record! It’s different skills, that’s all. You’ve still got to have it all up there [taps head], to know what sounds good and how to put it all together. It’s just that you don’t necessarily do it by playing guitar.

One of your earliest charges was Nico.

I don’t think I actually did her record; I did her test. She sang Blowin’ In The Wind in the most unusual manner. I wasn’t quite sure what to make of it, to be honest, but she was certainly something unusual. Very imposing too, about a head taller than me. When I heard her later stuff, it sort of made sense, though the music was so austere. I remember the session well, because Ari, her son, was with her and spent the whole time just tearing the studio apart. He was wild, running around and causing havoc.

You worked with an unknown Marc Bolan too. Was there any indication he was a superstar-in-waiting?

He definitely had something; he was different. I worked with him with John’s Children. They were ahead of their time, really. They wanted a track for me to put instruments to, which was just the German army marching. It was pretty strange. But Marc knew what he wanted to do, even then. It was never dull.

What about arranging She’s A Rainbow for the Stones?

The session itself was good, apart from all the hanging around and waiting for various Stones to show up. I was like, “Okay, well, it’s Monday today, will they be in tomorrow?” Then, come Friday, I’d get a call saying they’d be in next week. And so it went on.

In early 1968 you played on Donovan’s Hurdy Gurdy Man. Various players, including Donovan himself and engineer Eddie Kramer, attest that Jimmy Page played guitar, while John Bonham is rumoured to be on drums.

That’s one of those false rumours that’s been going around for years. Jimmy wasn’t on it. There was me on bass, Alan Parker on guitar, Clem Cattini on drums and Donovan on acoustic guitar. Eddie Kramer should know better, because he engineered that session and took pictures too. I know poor old Clem was trying to prove to the back-royalties organisation that he played on it. Nobody would believe he was the drummer, but I booked him!

What made you leave the session business?

One of the deciding factors was recording a ‘muzak’ session. As soon as it would start to get interesting, the producer would say: “Stop, that’s too much. This has got to be wallpaper music. It’s for people to hear while they’re going up and down in a lift”. I hated that session. In the end I’d just had enough; it was hard work. I was just feeling burnt out. And you probably know the story about my wife reading one of the music magazines and telling me that Page was looking for people to form a band with. She was sick of me moping about and wondering what I was going to do next. So in the end I gave him a call. It was scary joining Zeppelin, because being a session musician meant you were paid well. To then go into a band was no guarantee of making money. I had no idea if it would work or how long it would last.

In the very early days of Led Zeppelin, you were almost dismissed by the British music press as an irrelevance.

At the first Albert Hall show, it was generally thought that we were an American band. Nobody really wanted to know about us, press-wise, in England. They didn’t really get it. We were different from the other bands. We weren’t a white-boy blues band, or straight-ahead rock or Sabbath-type band, so we ended up going to America. We were bigger there than we were in England at the beginning. Then when we came back here, suddenly they were all over us.

Did you ever get to see anything other than the inside of planes and hotel rooms when you were touring with Zeppelin in the 70s?

I once read that The Beatles toured America and never left their hotel room, and that made quite an impression on me. I thought, I can’t do that. Robert had the hardest time, but I could sneak around without being recognised. I was able to walk about because I looked different on every tour we went on – short hair, long hair.

No one really expects you to be in a mall in the middle of Denver, so people are looking at you and saying to each other: “That guy looks a bit like John Paul Jones from Led Zeppelin. But it can’t be.” So you can get away with it. And when I was walking the streets, I didn’t have bodyguards or anything like that. I was very inconspicuous; I’m pretty good at melting into the crowd. I’d end up at people’s houses and I used to turn up at gigs in a VW bus full of hippies. It was a case of, “Follow the limousines, he’s with the band!”

Is there any reason why none of the members of Led Zeppelin has ever written a book?

There have been plenty of offers. Lots of people want to write books with us. One of the things you have in the back of your mind is that people don’t really want to know about the music, for whatever reason. And I don’t want to be dishing dirt on the band. And I’m too busy to be honest, too busy playing it to write about it.

Post-Zeppelin, you worked with a highly eclectic bunch of people; everyone from REM and Brian Eno to Butthole Surfers, Diamanda Galas and The Datsuns.

I never like to make the same record twice. And I can never do the same thing for any long period of time. I know it sounds strange, but to me all these different people are kind of the same. It’s all music that I like. If I feel I can do something for someone, then I’ll do it. And you learn something from every experience. Has it made me a better musician? Oh yes.

Your string arrangements for REM on Automatic For The People – songs like Drive and Everybody Hurts – were pretty radical for them in 1992.

They flew me over to Atlanta, where I met some members of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra. I didn’t conduct it, because I prefer to have a conductor there if I’m arranging. It was a great thing to do, I had a really good time on that one. REM just sent stuff over for me to do. It was as simple as that. Everyone knew what they wanted.

That same year you produced Independent Worm Saloon for the Butthole Surfers.

I had an American agent at the time, who said that Butthole Surfers were looking for a producer and my name had come up. So I left Georgia and flew to California, where I found a studio about half an hour outside of San Francisco. Not too far away so that everyone got cabin fever, but not too near so you’re always looking for people. So we all holed up and made this record, which I’m quite proud of, actually. Gibby’s amazing. He’s a very big talent and highly unusual.

Is there anyone you’re still gagging to work with?

That’s a very difficult one to answer. I would have thought it’d be interesting to work with Neil Young. There’s just something about what he does and the way he does it. Should he ever knock on my door, I’d probably say yes. He’s another person who doesn’t like to stand still.

When you took up Dave Grohl’s invitation to become part of Them Crooked Vultures, were you inundated with other offers too?

[Laughing] No! Though during the ’80s, I couldn’t get arrested. Nobody was interested. I think that was probably down to the baggage of Led Zeppelin. It was like Paul McCartney after The Beatles. When Dave called, I was still doing something with Jimmy Page. Then when that fell through I rang him up. Dave had to convince Josh I was serious, but he didn’t believe him: “Yeah, right. And I’ll call Obama.” I still don’t think he believed him until I walked into the studio for the first time. Then Josh suddenly went: “Oh shit, now what do we do?”

Did Them Crooked Vultures act as some sort of compensation for Zeppelin fans disappointed at the lack of activity following the O2 reunion?

Y’know, if you’re a Zep fan and really want to go see Zeppelin, you might as well go and see one of the better tribute bands. Even when we played the O2 we didn’t play the same as we did in the old days, because you just can’t. I like to think it’s because one is endlessly creative, but it’s more because you can’t remember things! It’s as simple as that.

Actually, Jason [Bonham] did. I remember in rehearsal getting to a point in one song where Page and I were stuck, wondering where we went from there. Jason said: “Well, in 1972 at the Forum you did it this way; in 1973 you did it this way and segued into this or that…” We played one number [For Your Life] where I said: “Y’know, I really can’t remember what I’m supposed to play on this.” Page went: “I’m finding this difficult too. Jason, why can’t we remember how to do this?” And Jason just said: “Because you’ve never played it on stage before!” We’d only played it once before, which was the day we recorded it – thirty-seven years ago.

Will there be a second Vultures album?

I think there will, but we just couldn’t fit it in before Josh and Dave went back to their day jobs. We do mean to, and it may be in a year or so. The will is definitely there, but they’ll have to finish what they have to do first. It was always thus. It was never going to be just a one-off, but at the same time it was never going to be a full-time thing. The Vultures sit somewhere in the middle. But yes, there’s certainly more to come.

Are there any fears that, with the Foo Fighters and QOTSA both back on the agenda, the Vultures might lose momentum?

We try not to think about this stuff. If it doesn’t happen this week, it’ll happen next week. It’s not a worry in that sense. We know what we want to do and we all seem to want the same thing. We never actually talk about the music. We don’t discuss anything, we just do it. It works out easier that way: don’t plan it, just get on with it. It really is a true democracy in that respect.

Aside from all that, what are your immediate plans?

I’m at the Royal Opera House in February, participating in an opera by composer Mark-Anthony Turnage called Anna Nicole [based on the life of the troubled late US glamour kitten Anna Nicole Smith]. I’ll be playing in the pit for some of the time, with the basses, and I’m also on stage playing with a jazz trio with [drummer/composer] Peter Erskine.

Knowing what you know now, is there one piece of advice you would have offered the John Paul Jones of the early 70s?

That’s a tough one. I can’t say: “Don’t say yes all the time,” because that’s actually the fun of it. Let me think… Probably: “Get it in writing.”

Originally published in Classic Rock magazine issue 153, December 2010

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2008, and sister title Prog since its inception in 2009. Regular contributor to Uncut magazine for over 20 years. Other clients include Word magazine, Record Collector, The Guardian, Sunday Times, The Telegraph and When Saturday Comes. Alongside Marc Riley, co-presenter of long-running A-Z Of David Bowie podcast. Also appears twice a week on Riley’s BBC6 radio show, rifling through old copies of the NME and Melody Maker in the Parallel Universe slot. Designed Aston Villa’s kit during a previous life as a sportswear designer. Geezer Butler told him he loved the all-black away strip.