Jeff Hanneman: Slayer's Quiet Man

Metal Hammer looks back at the sometimes reluctant Slayer guitarist who hated to travel, but loved and lived to play...

It’s all about perspective. Like anyone in the public eye, Jeff Hanneman was what the media said he was. If you believed the American tabloids, particularly in the 1980s, he was a Nazi- memorabilia-collecting, gore-and-Satan-obsessed danger to today’s youth. If you were a Metal Hammer reader, you’d know that he was one of metal’s finest creative minds, a blond whirlwind who played like a demon and wrote all-time classic songs.

But if you were lucky enough to spend time with the guy, you’d know that neither persona summed Jeff Hanneman up completely.

The truth is that he was a relatively quiet, introverted bloke with a dry-as-dust sense of humour, who never bothered to seek the limelight because it simply didn’t interest him. That’s pretty rare in heavy metal, as it is anywhere else. I was crushed when Hanneman died from liver failure on May 2, 2013. I wasn’t a close friend of his or anything, in fact I only got to interview him once, as opposed to the 30 or so interviews I’ve done over the years with the other members of Slayer. But in that hour or so of conversation back in 2004, I found myself really liking the guy.

I’d expected him to be more like his fellow axeman Kerry King, who is confident and outspoken, or like Tom Araya, Slayer’s resident philosopher. Instead, Hanneman was funny in an endearingly quiet way, painfully honest about his career, and inexperienced when it came to cynical journalists. If he didn’t know the answer to a question, he would admit it, but not in a defiant or cocky way: if anything, he sounded a bit unnerved.

Essentially, Hanneman was the kind of man who wasn’t afraid to admit his fears, and that’s always admirable. He once explained how his guitar playing compared to King’s, saying that at Slayer’s first rehearsal back in 1981, “I just remember I was scared shitless. I had been playing the least amount of time, so I sucked. I’d only been playing for like a month by the time I met Kerry, and after I saw him play I was like, ‘Oh man I gotta speed up the learning process’.”

Even after Hanneman’s guitar skills had evolved, he was fully aware that King was the more technical player. When I asked him if he knew that he had a slightly weird picking-hand style, he laughed: “Yes, Kerry always points it out. He says, ‘It’s very strange, the way you do that!’. But when we formed the band, I’d just started learning the guitar, and he’d had hundreds of guitar lessons. I was catching up.”

None of this stuff really bothered him, though. By his early 20s he had already written Slayer’s two best-known songs – Angel Of Death and Raining Blood – and knew where his greatest strengths lay. “I tried to emulate what Steve Vai and Joe Satriani did and really grow as a guitarist,” Hanneman once mused, before adding, “Then I said, ‘I don’t think I’m that talented, but more importantly, I don’t care’.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Metal Hammer, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Crucially, Hanneman cared more about Slayer as a whole entity than he did about his own individual fame. He wanted the band to succeed, so passionately n fact that he abandoned a short-lived 1980s side-project called Pap Smear simply because Slayer’s producer Rick Rubin told him it might threaten his main band’s fortunes. What’s more, although it seems ludicrous now, Hanneman feared that Slayer might be outdone by other Los Angeles bands in the early days of thrash metal.

As Strapping Young Lad/Testament drummer Gene Hoglan told me for a book I wrote in 2007 called The Bloody Reign Of Slayer: “Jeff came up to me and said,‘Dude, Dark Angel, I saw ’em back in LA – they’re faster than us, they’re better than us, they’re heavier than us!’. And I was like, ‘Dude, you’re in Slayer! What are you worrying about Dark Angel for?’.”

- Slayer frontman Tom Araya still misses headbanging

- Lombardo on Slayer: "I won’t ever be going back"

- Jeff Hanneman Remembered

- Every Song On Slayer's Reign In Blood Rated from Worst To Best

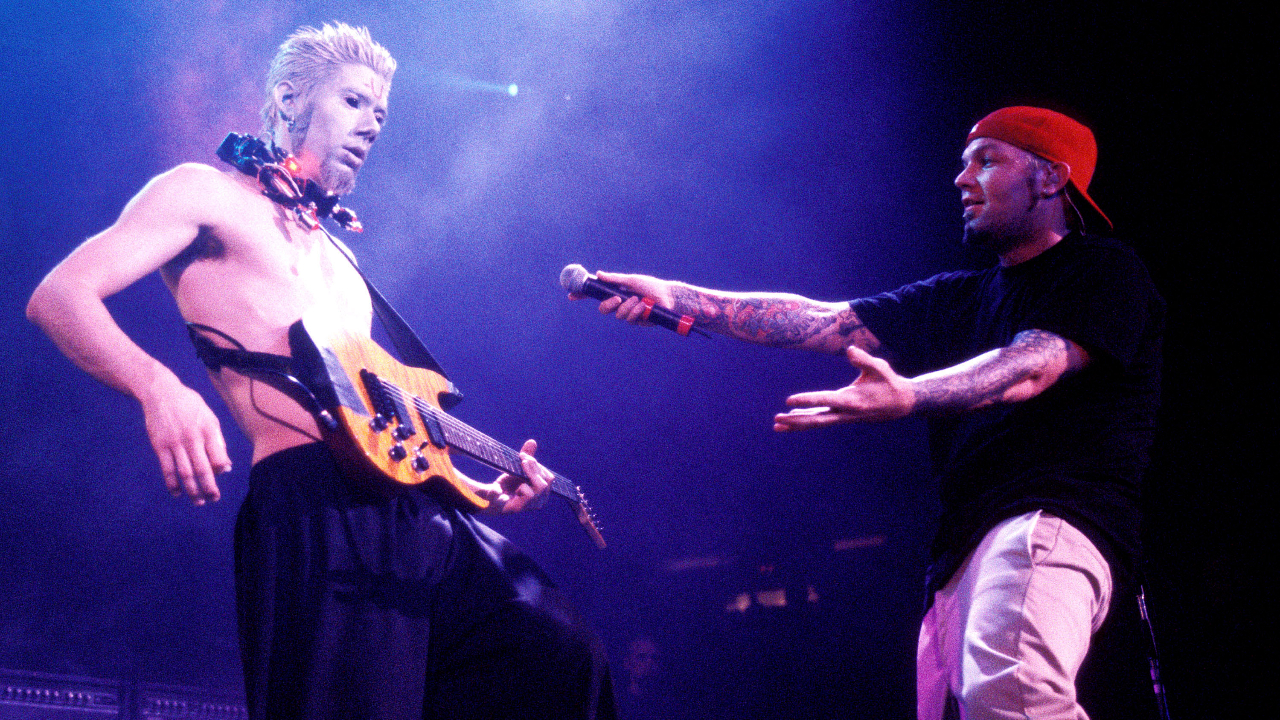

Once Slayer’s fortunes seemed assured as the heaviest and fastest member of thrash metal’s Big 4, Hanneman (pictured above in 1991 with Dave Mustaine, Scott Ian and Kerry King) relaxed into his role as author of the band’s darkest songs. While King is the more prolific, more ‘thrash’ writer, Hanneman also explored slower, more sinister territory in his songs. “There’s just something inside of me – this kind of evil atmosphere,” he said. “Every time I write something, it seems to find its way in there somehow. I like the dark side of music that gives you a mood – a certain sickness that makes you feel like hurting someone, or doing something evil.”

What’s most important there, given that this piece is trying to explore Hanneman’s personality rather than the bare facts of his career, is that he knew [and admitted] when his songwriting tastes led Slayer up a blind alley. I’m thinking, of course, of their 1998 album Diabolus In Musica, almost all of which Hanneman wrote as King was going through a fallow songwriting period. But Hanneman had been heavily influenced by the downtuned, sludgy tone of the nu metal sound, and one song in particular, Stain Of Mind, was a Korn-style slab of groove metal.

Many of us shuddered the first time we heard it, although Hanneman himself was upbeat about Slayer’s new musical direction. “The biggest difference between this record and Divine Intervention [its 1994 predecessor] was that I wrote a lot of this one,” he explained. ‘With Divine… I was in a rut and couldn’t come up with riffs I like. Before I knew it, Kerry had most of it done. So, with this record I really started working hard from the beginning. I was thinking, ‘What do I want to hear on this record?’. If it sounds modern, it’s because we’re into modern music and that shows. The one thing I like about this record is that it is moody, by the time you get to the end, it reads like a book.”

Not a book which many Slayer fans wanted to get into, unfortunately, but it says much about Hanneman’s character that he understood that fact. When asked a few years later why Diabolus… had been rejected by much of Slayer’s following, he shrugged and gave the dejected answer: “Well, we do what we do in the moment. Sometimes our albums turn out godlike, and sometimes they turn out lame. Sometimes people just don’t like what we do.”

Note that he could have been much more aggressive about his answer: he could have just told me to fuck off, as a lot of other musicians would have done. But that just wasn’t Hanneman. The same applied to Slayer’s all-time worst decision, their terrible 2006 cover of Steppenwolf’s Born To Be Wild. Hanneman laughed off his buddies’ endless piss-taking, explaining: “We were asked to be on a compilation, and we couldn’t think of a song. Time was winding down, so we just did it. After it aired on TV, I got phone calls from my friends saying, ‘What the fuck is up with that shit?’. I’m like, ‘Shut up. It was just a last minute thing. I didn’t have time to think it through, all right?’.”

The members of Slayer have never been close friends. Comrades-in-arms certainly, but not buddies and Hanneman was always completely open about that fact. While teenagers would look at pictures of Metallica in the 80s, rocking out in their San Francisco house and blasting the metal together, no such cosy fantasy would exist for Slayer. “We normally only see Dave [Lombardo] during rehearsals,” said Hanneman. “He prefers hanging out with his wife, which is fair enough. We don’t see much of Kerry either. Tom and I are the only ones that occasionally meet up socially – and that’s fairly seldom.” This is true of most bands, in fact, but few of them have the balls to tell it like it is.

No lies, no bullshit, just metal – that was how Hanneman lived, focusing his creativity on Slayer. He remained an inventive writer and innovator into middle age, dreaming up the shower of blood which Slayer took on the road in 2004, and filmed for the Still Reigning DVD (it says a lot about Hanneman’s ladiback character that he stood on the wrong spot, and the fake blood completely missed him). One of the most brutal songs of his career, 2006’s utterly pulverising Psychopathy Red, was written when he was 44. How many metal musicians can say the same? Sure, Hanneman became pretty jaded after close to three decades on the road. You would be, too. The lack of sleep, the tour bus diseases, the overenthusiastic fans – all these things combined to piss him off. He recalled: “There are nights when you’re sick and the last thing you wanna do is go up onstage. But when you get up you feel the energy from the kids, and it bounces back and forth. You feel great. Then the show’s over and you start to feel sick again. Once, a guy grabbed my guitar and started to sing the words right in my face. So I just hit him.”

Most of all Hanneman loathed travelling. It took him away from his home and his marriage to his high school girlfriend, Kathryn, which ultimately lasted much longer than those of most touring musicians. “The thing I personally hate out of this whole thing is travelling,” he said. “I hate airports, I hate getting in a van and going someplace… I hate the whole travelling aspect. Once I get to point B – fine. But I hate the actual travelling!”

However, to Hanneman, Slayer’s music was bigger than these petty grievances. When EMI India withdrew World Painted Blood, because the sleeve art was too blasphemous, he genuinely didn’t care. “I take it as a good thing. I actually do,” he guffawed. “When I heard about it, I just thought, ‘I’m the winner!’”

That’s a man laughing in the face of setback. Respect is due. At the age of only 49, Hanneman died three decades before his time and we can only mourn him for what he was – one of metal’s finest. The good die young, they say, but in Jeff Hanneman’s case we need to replace the word ‘good’ with ‘best’. RIP Jeff Hanneman.

This article originally appeared in Metal Hammer #245.

For more on Jeff Hanneman and Slayer, then click on the link below.

Joel McIver is a British author. The best-known of his 25 books to date is the bestselling Justice For All: The Truth About Metallica, first published in 2004 and appearing in nine languages since then. McIver's other works include biographies of Black Sabbath, Slayer, Ice Cube and Queens Of The Stone Age. His writing also appears in newspapers and magazines such as The Guardian, Metal Hammer, Classic Rock and Rolling Stone, and he is a regular guest on music-related BBC and commercial radio.