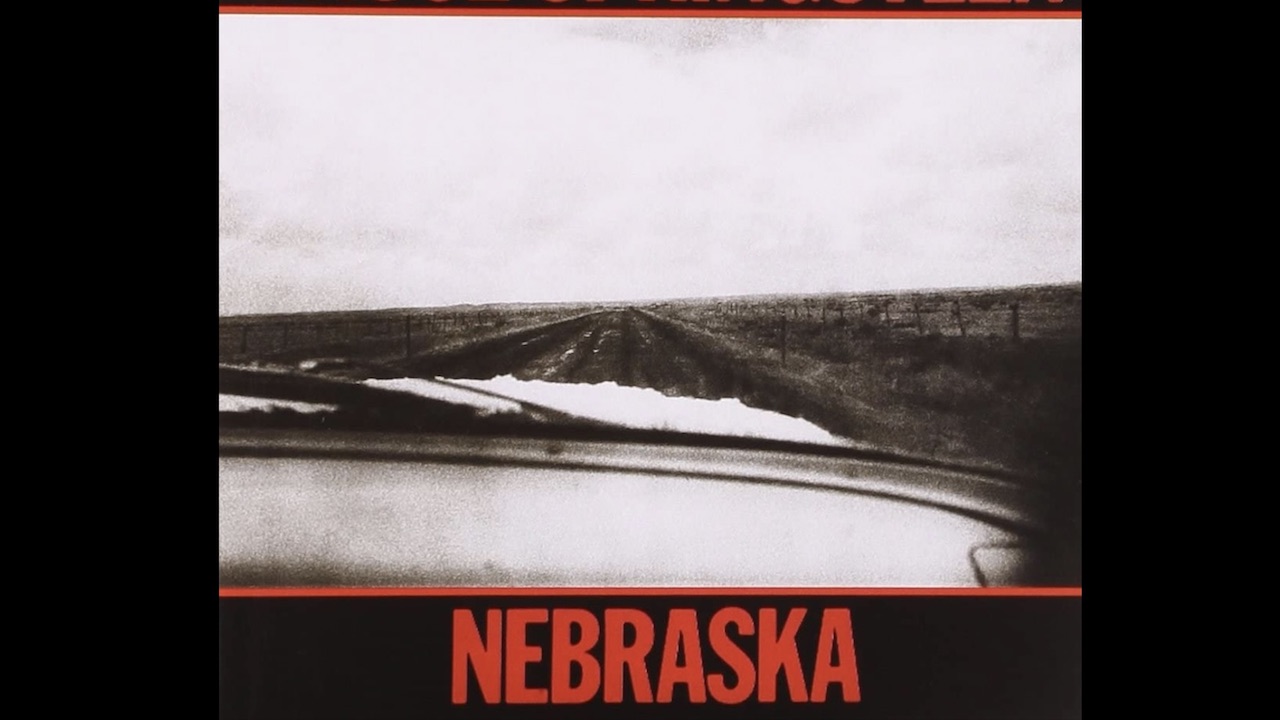

How Bruce Springsteen battled the "black sludge" of depression to make his brutal, lo-fi masterpiece Nebraska

Released on September 30, 1982, Bruce Springsteen's stark, dark sixth album might just be his best

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

It was after a draining 10-day road trip from New Jersey to Los Angeles that Bruce Springsteen walked into a psychiatrist’s office for the first time, started talking and burst into tears. At the age of 32, decades of pent-up feelings came flooding uncontrollably to the surface. Suddenly, the demons he’d been trying to outrun had finally caught up and came “spewing like an oil spill… [with the] black sludge threatening to smother” him.

It was against this backdrop that the masterpiece that is his 1982 debut solo album Nebraska was written and recorded, dipped in the ooze of the sludge that he confided to biographer Dave Marsh had left him feeling suicidal.

This was not the way that things were supposed to go. Following a successful, year-long tour showcasing the mammoth double set of The River, Springsteen had cemented his place as a global talent whose star was only set to rise further still. An intimate, largely acoustic solo offering was hardly in the playbook.

Nor was it intentional. When the New Jersey native set up in his Colts Neck bedroom with a $1,050 Tascam 144 cassette recorder on January 3, 1982, little did he know how important it would be. He thought he was sketching out demos for another E Street Band album. Of the 15 tracks recorded on that fateful evening, 10 became the songs that made up Nebraska, left almost exactly as they were initially captured, raw and unadorned save for some modest use of harmonica or tambourine. He’d walk around with that cassette in his pocket for weeks afterwards, oblivious to the precious power of the recordings contained therein.

Full band “Electric Nebraska” sessions were attempted a few months later, but re-recording the songs sacrificed something vital, stripping them of their dusty, dream-like quality, and so those efforts ultimately came to naught. Without meaning to, whatever stroke of fate occurred as the new year stretched into life that night would prove pivotal in the arc of Bruce Springsteen’s career. On September 30, 1982, one week after he had celebrated his 33rd birthday, Nebraska was released and for the first time, he didn’t head out on the road to play his new record for anyone.

The gentle irony in that is that many of the songs put its protagonist behind the wheel of an automobile. They survey the people and places they encounter, travelling as lost souls looking for connection as the world goes whizzing by.

But it’s in their stories that the most indelible marks are left. We meet serial killers, average Joes and small-time crooks, seeing life through eyes relaying tales of murder, hard times and desperation. The songs pit people in situations of utter despair, but no judgement is proffered. In fact, their predicaments are steeped in humanity that’s often relatable. These are mostly ordinary, everyday folks who have been pushed to the brink and driven to committing unspeakable acts. Through economic, matter-of-fact language their actions feel like the kinds of things anyone might be capable of, in the wrong circumstances. It makes some of their choices along the way all the more harrowing.

At its core, Nebraska underlines the fragility of the American dream and the pillars relied on in life – work, love, family and friends – to stay grounded. It’s a record that ponders what happens when those pillars crumble down and there’s nowhere left to turn. Two separate subjects cry out “deliver me from nowhere” (State Trooper, Open All Night) as an illustration of that fact. Fittingly, most of the action takes place in the middle of the night or just before dawn, when only bad things can happen. But even that action, such as it is, occurs in the spaces in between. The words are waypoints guiding the listener along. It’s in what’s not said, in what’s hinted at, when the imagination’s left to roam the record’s darkest corners, where the real menace is felt.

By Springsteen’s own admission the songs he penned in the midst of this depressive fug owe a debt of gratitude to the spirit of Bob Dylan, Hank Williams, the American gothic prose of Flannery O’Conner and the “quiet violence” of Terrence Mallick’s cinematic universe.

The title-track borrows from the latter most directly, inspired by a timely viewing of his 1973 feature, Badlands. Both song and movie dramatise the real-life story of 19-year-old Charles Starkweather and his 14-year-old girlfriend Caril Ann Fugate, who went on a killing spree across the country in 1958, claiming the lives of 11 people. Springsteen calls it a song of “disconnection and isolation” adopting the perspective of the outlaw fresh from his first murder, winding up with a chilling depiction of capital punishment and a shrug of an explanation that “there’s just a meanness in this world”, setting the tone for the rest of the record.

The lure of organised crime proves too great for the “honest man” of Atlantic City (originally called Fistful Of Dollars, after the Clint Eastwood movie), whose debilitating debts are piling the pressure on. A story of the haves and the have-nots is starkly portrayed in Mansion On The Hill, a real-life reminiscence from Springsteen’s childhood, where the symbolically unattainable conflictingly haunts his dreams now that he’s become a man who lives in such a place. Johnny 99 finds a laid-off autoworker begging for the death penalty after his arrest for shooting a night clerk. There’s the heavy drama of unravelling brotherly bonds in Highway Patrolman. While poverty, shame and frustrations play out through the eyes of a child in Used Cars.

On the penultimate track, My Father’s House inverts the biblical story of the Prodigal son. And sending the record home on a bleak note, Reason To Believe offers a nihilistic meditation on mortality, love and religious rites of passage. As a groom’s left stranded on the banks of a river on what should have been his wedding day, the final line wryly reflects how, “Still, at the end of every hard-earned day people find some reason to believe.”

It’s open to interpretation, of course. A more optimistic reading might hear those concluding sentiments as a glimmer of hope in the face of crushing hopelessness. But while resilience and human spirit thread all through Nebraska, danger and broiling fury dominate. It makes sense that these songs emerged from a head full of chaos. Because Nebraska never flinches in its determination to face the abyss. Its characters are too far gone to reduce their plights to bumper sticker platitudes. These are real stories and real life is often harsh.

In the midst of writing this music, Springsteen also drafted the first demo of Born In The USA. The songs for the record that it would eventually appear on two years down the line exist in sonic contrast to those found on Nebraska, but they bear spiritual resemblance, coming from the same time and similar wells of creativity. Those songs and that record would see him submit to a life of superstardom, playing in stadiums and becoming a staple of the pop charts.

By then he had long left behind the cripplingly shy kid who used to seek sanctuary in his bedroom mastering the art of guitar to help him find his voice. But in opening up for the first time about his private torment, it’s understandable that the person who went into that psychiatrist’s office and the one who emerged would be different. Nebraska marks the moment just before the dam broke and for Bruce Springsteen, things would never be the same again.

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

Formerly the Senior Editor of Rock Sound magazine and Senior Associate Editor at Kerrang!, Northern Ireland-born David McLaughlin is an award-winning writer and journalist with almost two decades of print and digital experience across regional and national media.