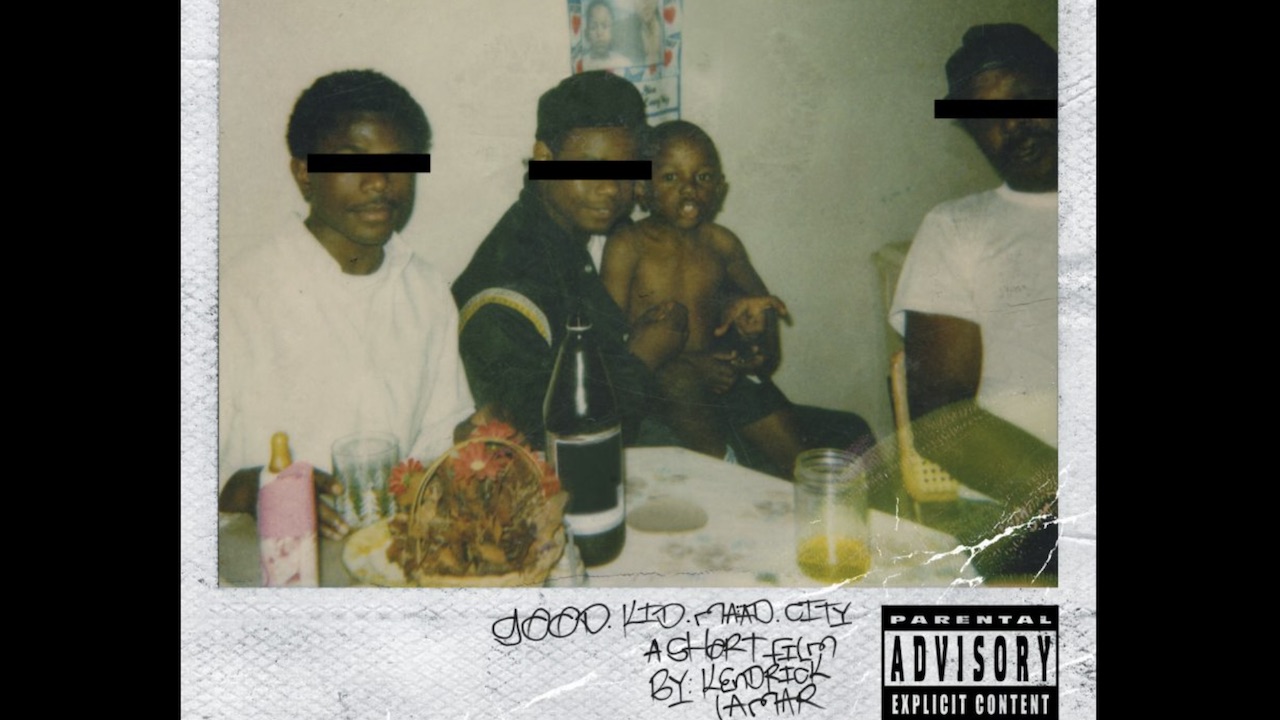

Great outta Compton: how Kendrick Lamar revolutionised hip-hop with the darkly poetic concept album Good Kid, m.A.A.d City

Released on October 23, 2012, here's how Kendrick Lamar's bold and brilliant second album ushered in a new golden age of hip-hip

The noughties was the decade in which hip-hop really began to overtake rock, indie and pop as the definitive youth culture music. It wasn’t always the easiest transition for many old school hip hop fans though, for while there were still important personal and socially conscious albums being released, swagger, bravado and the ostentatious flaunting of the trappings of stardom began to become dominant characteristics in the art of rap's biggest names. As aspirational and attractive as the lives that Drake or Lil Wayne detailed in their work may have been to many, they weren’t speaking to the lives that those buying their records were living. In that regard, many felt mainstream hip-hop had lost its way.

In this context it’s easy to see why Kendrick Lamar’s second album, and debut major label effort, Good Kid, m.A.A.d City made such an impact. Lamar had been performing and releasing music for nearly a decade, with his first mixtape Youngest Head Nigga in Charge dropping in 2003 under the pseudonym K.Dot when he was only 16 years old. He was a prodigy, his flow, cadence and the thoughtful, cutting insight he brought to his music displaying the intelligence of someone way beyond his years.

As his career progressed Lamar became a key name to drop, his profile rose at an impressive rate, but it was the song Ignorance is Bliss from his 2010 mixtape Overly Dedicated, the first after dropping the K.Dot moniker, that became the key to him finding another gear. The song detailed the brutality of gangsta rap, with every verse closing with the line “coz ignorance is bliss”, juxtaposing the violence he had just detailed with a subtle but powerful disclaimer. So forceful was the song that when it was heard by Dr. Dre, the legendary producer was compelled to sign Lamar to his own Aftermath Records imprint.

The Compton-born rapper was now a major label artist, signed by one of the biggest names in the genre. But rather than embrace the superstar company he was now keeping, Lamar made a conscious effort to remain grounded and continued to work with the in-house production team at independent label Top Dawg Entertainment, who had signed him as a teenager at the start of his career. He also decided to retain the narrative structure concept from his debut album Section.80 from the year prior, but this time use it to detail his memories and experiences growing up in Compton in the 90’s.

To find inspiration for the album Lamar went back to the neighbourhood of his youth, spent time with childhood friends, listened to the music that he grew up with and embraced the memories and nostalgia of the streets of the south LA city. Here, stimulated but conflicted, he began adding flesh to the thematic bones of his Aftermath debut. It was, as he told XXL magazine prior to the release of the record, about the fact that “The kid that is trying to escape that influence, trying his best to escape that influence, has always been pulled back in because of circumstances that be.”

As Kendrick began to write the album, embracing and inhabiting the characters from Compton to weave a portrait of the city, the sonic palette of the album grew ever broader. A more analogue-sounding, rich, dense, subtle production, which leaned in on the classic hip-hop staples of early soul, funk and R&B, began to accentuate the stories of the lives Lamar detailed. It was an approach that was utterly at odd with the most popular style of hip-hop of the era. This was no Cristal popping, bling encrusted bravado over 808’s, instead it was quintessentially earthy sounding and filled with the kind of self-analytical introspection that felt utterly unique to the rapper.

Released on October 23, 2012 Good Kid, m.A.A.d City went straight into the US Billboard 200 Chart at number 2, selling 242,000 copies in its first week, and becoming his first album to chart in the UK, peaking at number 19. It’s since gone on to sell three million copies in the US, and also reached Platinum status (300,000 copies sold) in the UK. The critical reaction was similarly gushing: it currently has a score of 91/100 on Metacritic, was named Album of the Year by everyone from the BBC to hipster website Pitchfork and was nominated in the prestigious Album of the Year category at the 2014 Grammys.

A decade down the line, Good Kid, m.A.A.d City has lost none of its power and potency. From the prayer that opens Sherane a.k.a. Master Splinter’s Daughter all the way through to the closing old school swing of Compton, including Dr. Dre’s only feature on the album, this is a breathtaking journey. The sound of the record is still fantastically dexterous, be it the deep bass throb of Backstreet Freestyle helping to paint the picture of a teenage Lamar boisterously rolling through Compton or the slow jam drag of Poetic Justice paying homage to Janet Jackson, it can be poured over even a decade later and there are still layers to be found. But, as gorgeous sounding as Good Kid, m.A.A.d City is, it would be churlish to suggest that Kendrick’s presence doesn’t dwarf everything else on the album.

Throughout the run time we find an artist wrestling with his culture, his identity and his purpose; expertly detailing the trauma of seeing bodies and death in his neighbourhood whilst also admitting he himself isn’t immune to embracing violence and retribution with the line “You killed my cousin back in ‘94, fuck your truce.”

The exploration of alcoholism, peer pressure and his family's dependency on the haunting club synth of Swimming Pools (Drank) is both instantly danceable whilst being truly unsettling. On the 12-minute-long album highlight Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst, he inhabits the voices of a late friend, his sister and himself, reflecting on his worth, purpose and life choices in a way that feels so real, so moving and so personal. It’s a song of such magnificent quality that its inclusion alone is enough to place Lamar in a class all on his own.

The latest news, features and interviews direct to your inbox, from the global home of alternative music.

Grounded, idiosyncratic and relatable to the people buying his music, yet still majestically talented, for anyone that had fallen out of love with hip-hop in the years prior to his ascent, Lamar felt the definition of an artist capable of acting as the tinder to reignite their passion in the genre.

Lamar would go on to top the album, and arguably create the most definitive musical piece of the 2010’s, with 2015’s To Pimp a Butterfly, turning him into one of the biggest artists on the planet. He embraced more socially conscious and less personal themes across his next few albums, and, in many ways, it wasn’t until the release of this year's Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers that we got anything that felt like something of a spiritual successor to Good Kid, m.A.A.D City. This set found him digging even further back, detailing his childhood trauma, generational wounds and his own personal growth from it. It’s another classic, but that’s a story for another day.

Toward the end of Good Kid, m.A.A.d City’s penultimate track Real, a song that seems to deliberately try to build Lamar up from the emotional rollercoaster the album has taken him on, a voicemail from his mother Paula Duckworth is heard. In it she tells her son to “Come back a man and tell your stories to these black and brown kids in Compton. Let them know that you were just like them, but you still rose from that dark place of violence, becoming a positive person. But when you do make it, give back with your words of encouragement. That’s the best way to give back to your city.”

Kendrick Lamar has given more than most, and Good Kid, m.A.A.d City is far more just a great album, it’s an album that kick started one of the finest runs in modern music and ushered in a new golden age of hip-hop. Spectacular in sound and legacy, this is the epitome of a true modern classic.

Stephen joined the Louder team as a co-host of the Metal Hammer Podcast in late 2011, eventually becoming a regular contributor to the magazine. He has since written hundreds of articles for Metal Hammer, Classic Rock and Louder, specialising in punk, hardcore and 90s metal. He also presents the Trve. Cvlt. Pop! podcast with Gaz Jones and makes regular appearances on the Bangers And Most podcast.