“Mitch Mitchell was a journeyman. He was hopeless. John Bonham, Ringo Starr, Charlie Watts… they’re a three or four out of 10”: An audience with Ginger Baker, rock’s most cantankerous drummer

From Cream to Blind Faith and beyond, this is how Ginger Baker revolutionised music

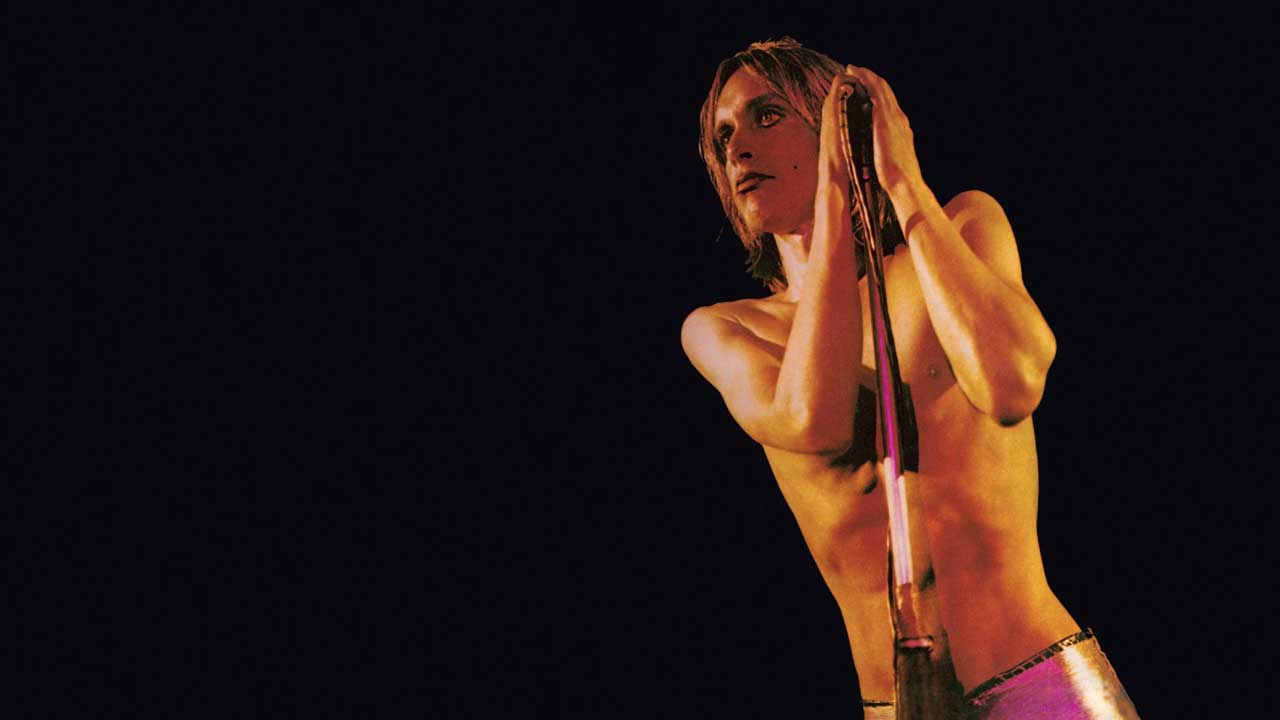

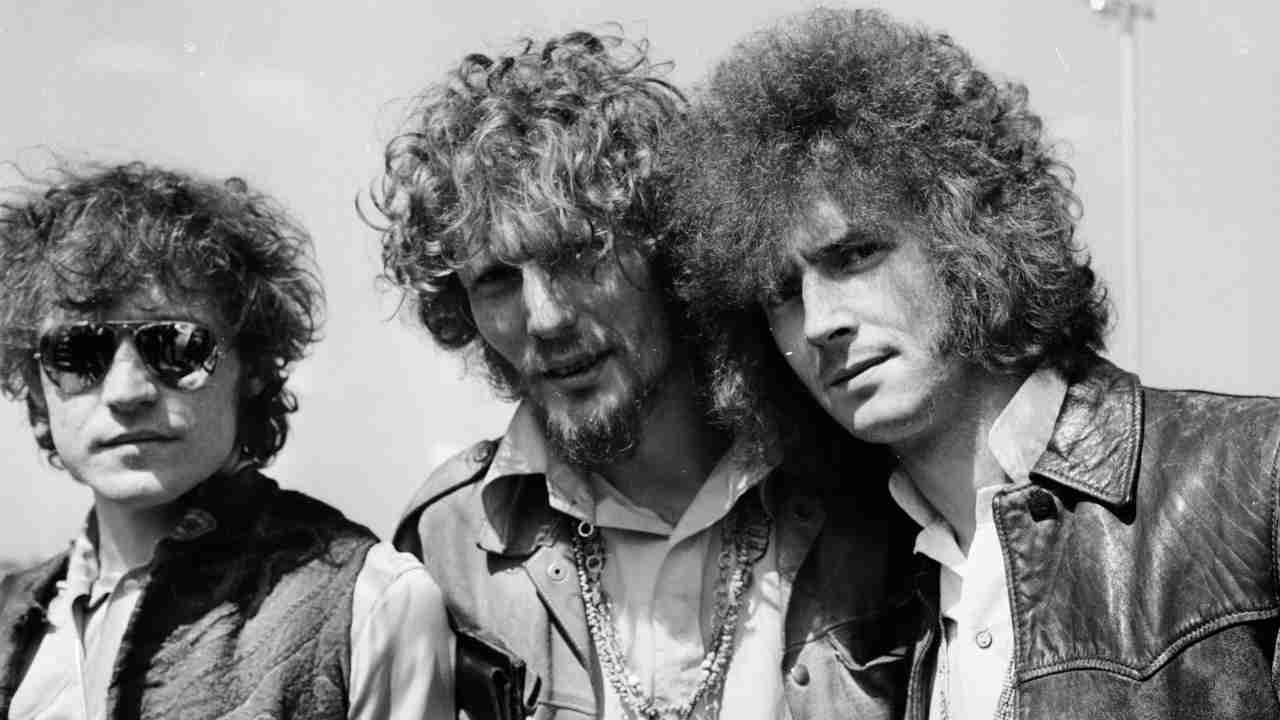

Surly, cantankerous and occasionally violent, the late Ginger Baker was nonetheless one of rock’s greatest drummers. In 2011, as the former Cream man prepared to release his autobiography, Classic Rock stepped into the lion’s den for an audience with a genuine one-off.

The World’s Greatest Drummer is lying flat out on a bed in a West London hotel room when the man from Classic Rock is ushered into his presence.

“’Oo are you?” he moans, barely taking a handshake before soundly berating his publicist for various unperceived slights. “What other fuckin’ interviews ’ave I got to do?” he barks. “What newspapers am I in? Sunday Times? What good’s that?” he snorts. “Why aren’t I in the Daily Mirror? Sort of paper I’d read. A proper bleedin’ paper.”

The World’s Most Irascible Drummer swivels a notch. He is evidently in pain from the chronic osteo-arthritis in his back, hips and knees, which he has long kept at bay with pills, potions, painkillers and heavy doses of prescription morphine. Ginger is also very deaf, and his eyesight is none too good either. No lover of the cold, the 70-year-old has got the heating in the room turned to maximum and he’s in a right old hump.

“Where’s my tea?” he snaps at his long-suffering girlfriend, Kudzai, a 27-year-old lass from Zimbabwe who he met on the internet and now lives with at his ranch in South Africa.

A flunkey arrives bearing pots of tea for “Mr Peter Baker”. Baker is very cross. “That’s it! See if you can put the tray on my toes; bounce it around, eh?” he snorts. His girlfriend’s young daughter pours the tea while he fires up a Rothman’s. “Come on, then, speak. Ask your questions.”

And good afternoon to you too, Ginger Baker.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

The drum legend is back in London from his adopted home in Tulbagh, Western Cape Province, to promote his recently published autobiography, Hellraiser. It’s an extraordinary account of a life, punctuated on every page with mind-boggling accounts of heroin abuse, social dysfunction, fist-fighting and musical escapades in post-war Soho, the Swinging Sixties and beyond. It’s a car-crash read – literally and figuratively. Ginger makes enemies at every turn. Friends are few and far between, although bankruptcy and fiscal disaster have kept him company.

Baker was also in London to attend the Classic Rock Roll Of Honour and receive an award, and play a rare gig at the Jazz Café, which was attended by one former Cream bandmate, Eric Clapton, but not the other, Jack Bruce, who underwent a liver transplant a few years back and didn’t get a Get Well Soon card from Baker.

“Eric Clapton is probably my best friend,” Ginger says. “Him and Stevie Winwood. Eric is like my younger brother. I’m very proud of him. He’s done very well for himself. I didn’t realise he had such a following when I met him before Cream. I used to see ‘Clapton is God’ written on the wall but I was unaware of that. I’m unaware of most things.”

Recalling his first proper meeting with Baker, in the mid-60s, Clapton said: “He came to see me play with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers in Oxford and asked me to form a band. I was frightened of him because he was an angry-looking man with a considerable reputation.”

According to Baker, Eric said: “I know you, Ginger. You’re not such a hard nut as you think.” The guitarist, more a lover than a fighter, recalls being impressed by Ginger’s physique: “He appeared physically very strong, also extremely lean, with red hair. And he had a constant expression of disbelief mixed with suspicion… Later I also saw he was a very shy and gentle man, thoughtful and full of compassion.”

That night Baker drove Clapton home to West London from Oxford in his new Rover 3000. Driving like a maniac, he nearly crashed the car on the A40 when Eric suggested Jack Bruce as the bass player for their new venture. Ginger’s first reply was a flat no. A few days later he phoned Eric and told him he’d changed his mind.

Before Baker and Clapton extricated themselves from the Graham Bond Organization and Mayall’s Bluesbreakers respectively, the fiery drummer had already shared stages with Bruce, the classically trained and gifted Scottish bassist. The antipathy between Baker and Bruce is well known and well documented. But surely their feud, which goes back decades, is based on a love/hate relationship?

“Not at all,” Baker counters. “I found Jack in 1962. I got him into all the bands we worked in, including Cream. I was the catalyst. He had ego problems once Graham Bond got him to sing [during Bruce’s tenure in the Graham Bond’s band]. Even today Jack refuses to accept that I’m anything other than a drummer. He admits I’m a wonderful drummer, but he won’t admit I’m a musician. I write music.

“Same with Pete Brown [Cream’s lyricist, who at the time of Cream was working with his highly regarded band Battered Ornaments]. I first saw him during a show at St Pancras Town Hall in 1961. When it comes to Cream, he just says he got ‘a phone call’; won’t say it was from me.”

As Ginger sees it, the Bruce/Brown axis tried to usurp him and Clapton within Cream from the off.

“We all contributed on our songs,” Baker protests. “The ones that piss me off are Sunshine Of Your Love and White Room. I was a major part of those tunes – the whole bolero 5/4 thing [in White Room], I got no credit. Years later, Jack goes mad because Eric’s playing White Room in his set! That’s Jack, I’m afraid.”

Running sores continue to erupt. Cream’s reunion shows at London’s Royal Albert Hall in May 2005 (also the scene of the band’s farewell concert in 1968) were received as a triumph. Ginger got out his mallets for We’re Going Wrong, and turned back the clock with his legendary drum solo vehicle Toad. The crowd went nuts. A three-minute ovation. The three old geezers were up to their old tricks, and that was the kind of indulgence the audiences paid top money to witness. But by the time Cream did some more reunion shows six months later, playing three nights at Madison Square Garden, the bad karma returned.

“Jack’s behaviour was different,” Baker says. “He behaved like a prick, grabbing the microphone, dancing all over the stage. The Albert Hall was one of the most enjoyable gigs I’ve done; Madison Square Garden was a fucking disaster. Jack apologised to me afterwards because he’d freaked out at me in front of the whole audience for playing too loud on We’re Going Wrong. That was the last straw. He thinks he can do that then say sorry? It was why we split up in the first place.”

According to Baker, Bruce and Brown still earn more money from Cream’s royalties than him and Clapton. “Does that seem right?” he says. “I got a letter from Pete Brown telling me I should be grateful to him for writing all these wonderful words so I can earn money! I can’t stand either of them. They stole Cream from Eric and me. I insisted Eric got a writing royalty on Sunshine…, and I thought someone would say: ‘What about old Ginger, then?’ Nah. It was totally unfair. Eric used to come to rehearsals and say he’d got a great riff, and Jack would retort: ‘Well I’ve got a lot of finished songs,’ and if we didn’t play ’em he’d throw a fucking tantrum.”

The animosity in Cream’s rhythm section was a fixture with a murky past. After one altercation in pre-Cream days, when Baker threatened to kill Bruce, he made a pact that he would never get violent with the bassist again. Maybe anger management counselling would have helped?

“Of course it fucking wouldn’t have helped! My solution was to go the bar and down as many as possible until I forgot. Otherwise I’d have gone back and hit him.”

The personality clashes between Baker and Bruce reached a peak during Cream’s lengthy tours of the US in 1967/68.

“Musically they were great, like a well-oiled machine,” says Clapton. “Personally it was a different matter, they rubbed each other up the wrong way. It got to the point where we never socialised any more, or shared any ideas; we got on stage, played and went our separate ways. So that was it for Cream. It just fizzled out.”

He probably didn’t miss Bruce, but Baker evidently missed the limelight after Cream split up in 1968. Bruce was working on his first solo album (Songs For A Tailor), and Clapton was now a bona fide superstar who had played on The Beatles’ White album and appeared with The Rolling Stones and John Lennon at the Stones’ Rock And Roll Circus extravaganza.

Feeling somewhat miffed, Ginger drove to Steve Winwood’s Berkshire cottage one night with a new proposal to put to him. Clapton and Winwood were inside getting royally stoned when the fiery figure of Baker loomed at the door. While young Stevie was overjoyed to see him, Clapton felt a familiar dread returning.

Reticent as ever, Clapton was nevertheless eventually cajoled into a new alliance with Winwood, Baker and former Family bassist Rick Grech. Named, ironically, Blind Faith, the new ‘supergroup’ debuted at a free festival in Hyde Park on June 7, 1969. However, that show was nearly cancelled when Clapton thought the drummer was back on heroin [Ginger claims otherwise in his biography]. In any case, Blind Faith evaporated after one album and a handful of shows.

It wasn’t the only gig of Ginger’s to be over almost as soon as it had begun, a couple of examples being unlikely stints with John Lydon’s post-Pistols outfit Public Image Limited and an unhappy alliance with space rockers Hawkwind (playing on 1984’s Do Not Panic, This Is Hawkwind).

“Yeah, I played drums on his track Rise [on PiL’s Album] in 1986. And it’s incorrect to say I didn’t meet him. I met him on several occasions. He was a bit of an odd guy, to say the least. The first time I met him he was sitting in a room cutting his finger nails with a razor blade. Then we met at various sessions. Me and [acclaimed jazz drummer] Tony Williams from Lifetime both played with PiL. It made me laugh later, because the reviewers never knew who was playing the drums on that record. I can’t even tell myself, and to be honest. I didn’t give a fuck. I just took the money. Me and Tony had a good laugh about that gig.”

As for playing with Hawkwind in the mid-80s: “That was the biggest joke in history,” Ginger scoffs. “I needed the money, and that was the only reason. Sadly I never saw what was offered, because they didn’t have any money. Hawkwind were more interested in their stage appearance and their lighting than their actual music – and their music was fucking appalling. Atrocious. I hated it all. Thank Christ I wasn’t with them very long.”

Despite the pair’s explosive history, in 1994 Jack and Ginger again found themselves in an uneasy alliance, this time with Gary Moore in what would prove to be another short-lived venture, the decidedly Cream-like BBM. Baker, who had lost substantial fortunes on various Nigerian adventures, and with an expensive polo hobby to support, agreed to the BBM project only if he got good money and also First Class airfares from Colorado to Europe.

“As usual I received profuse apologies from Jack for his past behaviour,” Ginger says. “And the studio sessions we did delighted everyone, even though he was acting like my boss again and treating me as a session player. A tour was suggested; I’d get £50,000 a gig. What I didn’t realise was that Gary Moore was playing so loud that he blew his ears – just as Jack done to me. More gigs were cancelled than played. And they were awful anyway. Unlike Cream, everything with Gary Moore was contrived. Every solo he played was the same. I like to improvise.

“Unknown to me they organised a rehearsal at Brixton Academy, and when I got there I could hear Gary Moore’s guitar outside on the street. We played it note-perfect, as usual – should have been the fucking gig. The next day his manager phones me and says Gary’s blown his ears again and they’ve taken him to the doctor. I said: ‘Why don’t you take him to a fucking psychiatrist, cos that’s what he needs.’ That wasn’t the right thing to say to Mr God Almighty.”

But it was funny.

“Yeah, it was funny until I got the bills for retrieving my gear from Berlin, and paid for my polo horses to be taken to Boston, which they were gonna cough up for. And didn’t. My credit card bill wasn’t fucking funny.”

Fifteen years later, memories of BBM still throws Ginger into a rage. “That’s why I’m not happy with the cover photo of my book, cos that picture of me was used on the album cover [of BBM’s Around The Next Dream] where I’m standing in front of angel wings, smokin’ a cigarette. It’s a cool picture with very bad connotations. That was a terrible time, playing with the Pampered Pompadour Of Pop. One gig in Paris was cancelled when he cut his finger opening a fucking tin. Eric would have put a plaster on and played. Oh no, not Gary. And Jack became Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde again. He didn’t like his hotel room; his family didn’t rate the view. He didn’t want the Mercedes, he desired a limousine. For a 10-minute ride to the gig? Hello? It was ludicrous. And, again, it was so loud I had to have baffle boards on either side. I hate volume. Why does rock music have to be so loud? That was rock’n’roll finished for me.”

At the publisher’s request, Ginger devotes a short chapter of Hellraiser to Jimi Hendrix. He softens slightly at the mention of his name. “A great player,” Ginger says. “Better jamming than he was in front of an audience. I wasn’t impressed when [Hendrix’s manager] Chas Chandler asked if Jimi could sit in with Cream. I didn’t know who he was then, just some geezer, and he starts going down on his knees, playing guitar with his teeth. I wasn’t impressed at all.”

Still, on October 1,1966 at the Central London Polytechnic, Hendrix joined Cream on stage for an incendiary version of Howlin’ Wolf’s Killing Floor, complete with behind-the-head picking and flamboyant splits – most of his moves copped from Eric’s hero, blues legend Buddy Guy.

“Eric liked Jimi, and I got to know him as a person and we became very good friends,” Ginger says. “We were going to get some music together in 1970 after Blind Faith ended, but he ended up picking the wrong chick, Monika [Dannemann]. She was responsible for his death. He’s in bed with a chick and he’s sick and she runs out, leaving him in his sick? Disgraceful. When they picked him up he was cold,” Ginger wails. “He’d been dead for four hours. And that night we’d searched everywhere for him. We were going to invite him round, cos we had a big bottle of cocaine. If he’d done some coke,” Ginger laughs darkly, “he’d be alive, he’d never have gone to sleep. I had good times with Jimi. He used to come to my house in Harrow for dinner. His thing was pulling chicks when he was on stage. We shared a few.”

So many rockers have played the ‘I could have saved Jimi Hendrix’ card. Why was Ginger’s hand any different?

“I told you!” he shouts. “We was gonna play moosic together! I don’t know what we’d have done. It was early days. Stupid question. Bloody hell. I was very keen on it and it would have happened. Unfortunately it didn’t.”

As the Swinging Sixties faux psychedelic military world of Sgt Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band became a battleground littered with casualties – live fast, die young, leave a good-looking corpse – Ginger found himself increasingly sidelined (Whinger Baker) while lesser talents, in his view, alchemised rock into gold. He knew them all and didn’t rate many, remaining convinced that his original drummer heroes – Elvin Jones, Phil Seamen, Max Roach, Philly Joe Jones, Art Blakey – soared above the emergent superstar elite.

“Keith Moon as a drummer? Nah. He was good with The Who, I suppose, when he tried to play like me. I liked Pete Townshend. His dad was an old jazzer in the Squadronnaires, sax player, so Pete’s from a proper background. He’s another one who blew his ears out, like me. Those stupid Marshall amps are to blame.

“Moonie was a wonderful guy, but if you’re going to judge from minus two to 10 then I’m a golden 10. Mitch Mitchell was a journeyman. He was hopeless. John Bonham, Ringo Starr, Charlie Watts… they’re a three or four. I like Charlie, he’s a good friend since the old jazz days and he’s perfect for the Stones. He got me a gig with Alexis [Korner’s Blues Incorporated] and I recommended him for the Stones. But I hate the Stones and always have done. Mick Jagger is a musical moron. True, he is an economic genius. Most of ’em are fucking morons. Phil Seamen told me: ‘These pop musicians wouldn’t know a hatchet from a crotchet.’ Paul McCartney boasts he can’t read music! How can you call yourself a musician, then? John Lennon was the best musician in The Beatles by a country mile. He was a very talented guy. But George Martin was The Beatles. Without him they’d have been nowhere.”

That’s a contentious opinion.

“Fucking true an’ all. I remember it was the day my son was born, and I was doing a session with George Harrison for Billy Preston – That’s The Way God Planned It. And that didn’t last long. He [Harrison] was like Jagger, didn’t know what the fuck he was talking about. His way of explaining an idea was to wave his arms about. He’d be going: ‘Y’know, Ginger, play it like this,’ flailing his arms. What the fuck are you talking about! Write it down so I can see what you mean. He couldn’t.”

To say that Ginger doesn’t suffer anyone gladly is an understatement. The way he sees it, rock ‘musicians’ are adept at accumulating fame and wealth but otherwise exist in a talent-free zone. “Fucking idiots, most of ’em. When Cream were inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame [January 1993] it made me sick. Who was that bloke… Dick Morrison?”

Jim Morrison?

“Him. His band [The Doors] made all these fucking speeches, thanking their parents, their uncles, the dog… They all did it. Took about eight hours before Cream got to play our gig, which was why it was so terrible. All that rubbish. I was with Eric on his table when he was with Naomi Campbell – gorgeous chick she was, we got on very well – and we were bored fuckin’ rigid. Even cocaine couldn’t have kept you awake.”

After an hour or so of Ginger’s grousing about how banal and terrible rock’n’roll is, he lets slip that there is actually something, or someone, that he likes: “Kelly.”

Kelly Jones?

“‘Oo? Kelly Rowland, from Destiny’s Child. She’s my favourite. Beyonce is okay. I’m not keen on the track When Love Takes Over, but her voice… she’s like Whitney ’Ouston. And she’s a very beautiful girl, dances like you wouldn’t believe. Otherwise, nah. Modern pop is rubbish. And I don’t like the music business at all. I was with Cream on Atlantic for how many years? And I still got a letter one day addressed to Miss Ginger Baker! ’Ow do these people get a fuckin’ job?!”

As the afternoon shadows lengthen it becomes apparent that Ginger has had enough. He has few regrets about his book apart from the fact that it peters out towards the end, thanks to a sub-judice wrangle with a South African bank teller involving embezzlement, and a scar on Ginger’s genitals.

“The book says ‘fuck’ too much for my liking,” he adds, “but my daughter Nettie, who wrote it with me, says that’s how I speak.

“Wife two and three? I never speak to them. My first wife Liz is different. She’s my best friend. Very loyal, is Liz Baker. I wish we could get on better,” he sighs. “We argue too much. When we talk we end up putting the phone down. But she’s a good girl. She’s the only one who was.”

And on that conciliatory note, The World’s Greatest Hellraiser falls asleep.

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 142, February 2010

Max Bell worked for the NME during the golden 70s era before running up and down London’s Fleet Street for The Times and all the other hot-metal dailies. A long stint at the Standard and mags like The Face and GQ kept him honest. Later, Record Collector and Classic Rock called.