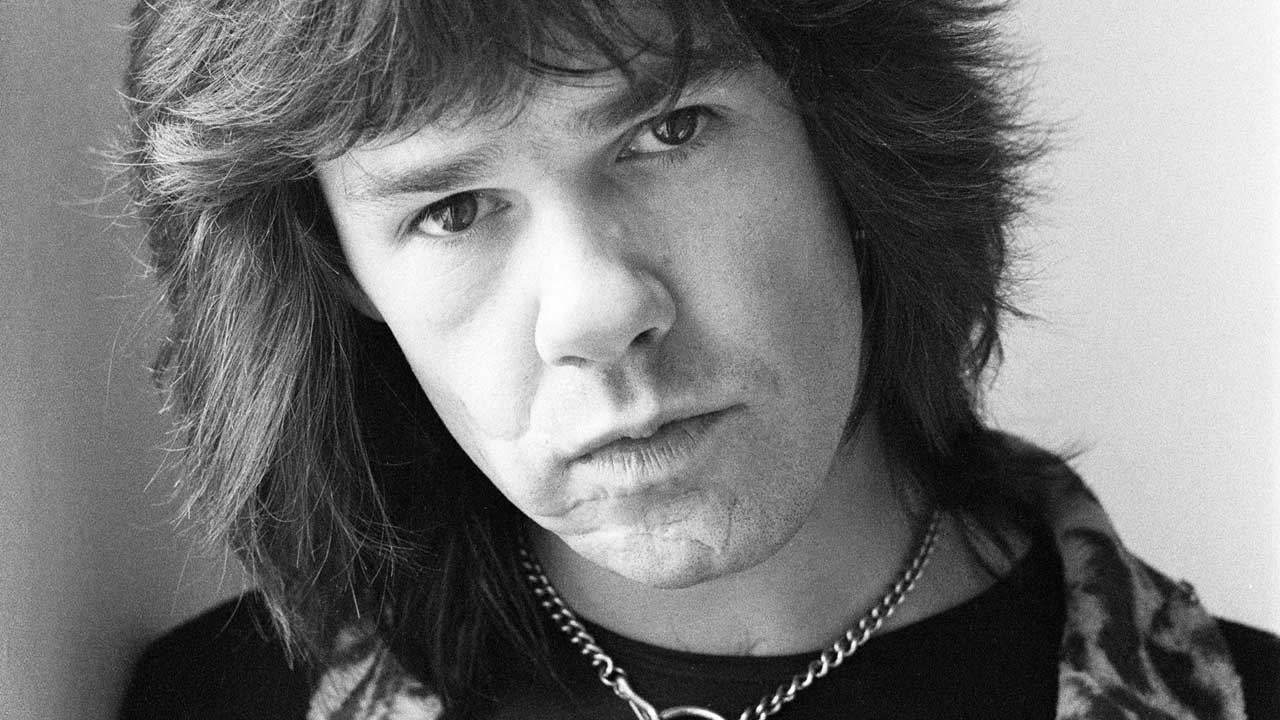

Gary Moore: leaving Thin Lizzy, the story of G-Force, and the terror of success

In June 1979, Gary Moore sensationally quit Thin Lizzy mid-tour. In this exclusive extract from his official biography, we look back at his post-Lizzy period and the formation of G-Force

Gary Moore had walked out of Thin Lizzy in the middle of a major US tour in July 1979. What next for the guitarist? Was he left high and dry? Absolutely not. Gary’s business manager did a deal with another client, Jet Records, to release his first proper solo album, Back On The Streets.

Jet Records was established in 1974, and was owned by the one and only Don Arden. The label scored an immediate hit with Lyndsey De Paul’s single No Honestly. But it was ELO – selling millions of albums worldwide and breaking into the US market – who established Jet Records as an international player and enabled Don to open an office in Los Angeles.

Don had mixed it with some notoriously shady businessmen and outright gangsters, where violence and intimidation were often just a wrong word away. So he was convinced rock’n’roll was a man’s world. His daughter Sharon would prove him wrong. Just as feisty, ruthless and uncompromising as her dad, Sharon wanted her share of the cake. While Gary was signed to Jet Records for recording, he was signed to Sharon for management, her first foray into the world of rock.

Why Gary? Obviously he was an outstanding guitarist, but not just that – the ‘guitar hero’ was coming back into fashion, and the main catalyst for that was Eddie Van Halen. Van Halen’s first two albums were worldwide hits straight out of the blocks, essentially setting up the heavy rock explosion of the 1980s and introducing Eddie’s groundbreaking guitar technique.

Gary first came across Eddie on the 1978 Thin Lizzy tour. Apparently, having watched him for the first time, the rather worried Irish guitar player went straight back to the hotel to try out this two-handed tapping business. Although in interviews Gary could be a bit indifferent about Eddie’s playing, they certainly appreciated each other’s technical skill. Eddie was sometimes spotted at Gary’s concerts, hopping up and down with delight in the wings as Gary would reel off a lick, look at Eddie and they would both laugh.

The other appeal of Gary for Jet was the success of Parisienne Walkways, which, while it did nothing in the States, showed that Gary had the potential to compose the sort of power ballad that brought significant chart success for bands like Foreigner and Styx, heralding so-called pop metal as another fashionable genre on the US market for the next decade.

For her part, Sharon reckons that Gary leaving Lizzy “was one of the worst mistakes of his career. Lizzy were just breaking, and they were gaining momentum in America. It was the perfect tour for them, and he just fucked it up. And you never get that momentum back again.”

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

And she was right, they didn’t. But whether all the blame for this can really be laid at Gary’s door, when Phil Lynott and Scott Gorham were in such a state, is highly debatable. Gary had a deal – now he needed a band. Gary and Mark [Nauseef, drummer who stood in for Brian Downey on Lizzy’s late-1978 tour] wanted to play together; Gary had told Glenn Hughes he wanted to form a band with him; Mark knew Glenn from playing on Glenn’s 1977 solo album Play Me Out.

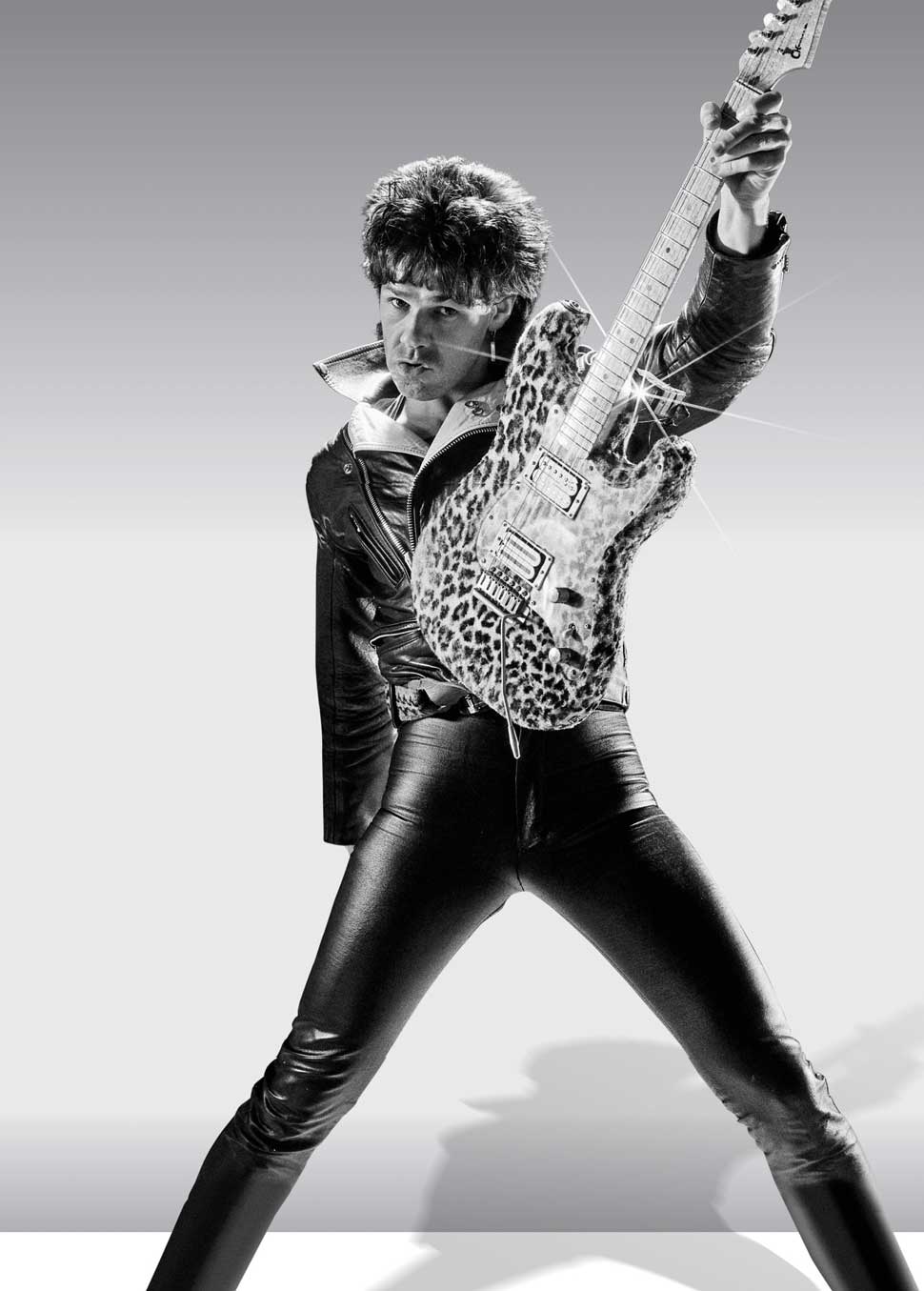

The stars were aligned. This was clearly a Gary Moore solo project: the band was originally titled Moore, but for some reason Jet thought this would be confusing, so the name changed to G-Force after Gary told Mark that at school he was known as ‘G’ by some of his friends.

“The band was clearly built around Gary and his playing,” says Mark, “and they were mostly his tunes as well. I reckon this trio was unique; there was Gary’s playing, Glenn playing Fender Rhodes [piano] with Taurus bass pedals. It was like power soul. Really killing.

"We got together every day and were rehearsing and writing in rehearsal places around LA, and went into the Record Plant to demo what we were writing. But it bothers me to this day that this trio didn’t happen. The management dug the band, Sharon was right behind us. They took good care of us, spent a lot of money – crew, rental cars, retainers and other expenses – but were never breathing down our necks. They’d just come down to the studio, check it out and leave."

Unfortunately, Gary was walking from one chaotic bassist/vocalist situation into another. In short, Glenn Hughes was a mess. Or, as Sharon now expresses it in her own inimitable fashion: “He was out of his fuckin’ mind. All you got out of him were sheep noises.”

“There were very few people in the industry who weren’t doing coke,” says Glenn, “and Gary was one of them – he hated that drug. I just adored Gary and we were becoming really, really good friends. He never spoke about the coke directly, but if we were at the Rainbow bar and grill and people were snorting coke off the tables, you could tell Gary didn’t like it. During that time when Gary was going to stay with me, just before he left Lizzy, I thought: He’s going to be a guest in my house. Surely I can stop this for a while? And I did.

“But anybody who is an addict or an alcoholic can only hide their addiction for so long before they start digging back in the bag. I was a bit high-maintenance, and I didn’t realise I had a problem. My lifestyle was really not marrying with their lifestyle, which was more of a drinkers’ club – Sharon and David (Arden, who co-ran Jet with his dad), Mark and Gary were all drinkers, and if you are an addict in that set it can rub against the green. Eventually it will spoil the party.

“It would have been in August 1979, my twenty-eighth birthday, and Sharon had a party for me at La Dome on Sunset Boulevard. I got really drunk that night, fell into the cake trolley and dislocated my shoulder. Sharon was laughing her arse off, and I got really upset and angry and apparently I said I was leaving the band – which I don’t remember saying, by the way.

"So, the next day, I got a call from Sharon about 11am and I asked her what time we were starting, and she said: ‘Well, we ain’t because you left the band.’ I tried to back down and say I didn’t mean it, but Sharon can be pretty brutal and she said I needed to get my shit sorted out before I did anything else. So that was the first time ever I’d lost a gig due to my addiction."

Glenn talked about being “high maintenance” (no pun intended), and this would have been the coke talking. As much as Gary would have hated heroin, he would have despised coke just as much because it makes people completely obnoxious and impossible to deal with.

In certain industries, and the music business is a prime example, part of the job description is to be the baddest guy in town, to be in people’s faces, in control and on top of your game. Coke will do that for you in spades – at first. And then all sorts of anxiety and paranoia sets in and, in the end, everything can fall apart, nobody wants to know you. And that can happen in months rather than years.

So, explains Mark: “We are in a spot because we knew we weren’t going to get another guy like Glenn that does all the singing and playing at such a high level. He was writing as well. He had been working with Ray Gomez and Narada Michael Walden; they had cut some things, so Glenn was bringing some great tunes – hard and heavy, but very melodic and soulful too.” In other words, a perfect complement to Gary’s playing and his approach to composition. But they had to start looking elsewhere.

“We auditioned all kinds of people down at Frank Zappa’s place. It was a real nice room. All of them were really good, but we weren’t sure what we were looking for except we would know it when we heard it.

“We both knew Tony Newton from Tony Williams Lifetime. An absolute killer bass player. He’d played with John Lee Hooker at sixteen, backed The Supremes at seventeen, he’d been the musical director for Smokey Robinson, toured with the Stones and Stevie Wonder. He’d also been on a record called Sunshower by German pianist Joachim Kühn with Jan Akkerman and Ray Gomez.

"I called Tony up and he came down to check it out. He brought a tremendous energy out of Gary. He had a double-neck bass with drone strings on it – he really went for it. Tony could sing, but he didn’t want to be an ‘out-front’ singer like Glenn. Gary didn’t want to be the lead singer either, so he could play more.”

Sharon reckons it took about eight months to get the album together and, in a re-run of Colosseum II, the main issue was trying to find a singer.

“It’s so hard to find a lead singer for a band,” she says. “The great guitar player and the great lead singer, that’s your winning combination, and it’s like gold dust to find it.”

Gary and Mark finally looked in their own back yard: “That album Sunshower had two vocal tracks on it, which was Willie Dee,” says Mark. “So when Gary and me were talking to Tony, we mentioned the singer because the vocal tracks were good. Willie came down, and he was in that same blue-eyed soul tradition. And there we were.”

Willie Dee (born William Daffern) had been in the third incarnation of cult 70s band Captain Beyond, which was originally formed from former members of Iron Butterfly, Deep Purple and Johnny Winter’s band. Dee joined Captain Beyond for their third and last studio album, Dawn Explosion, released in 1977. The band broke up about a year later.

Ggetting the new band together was one headache, finding the right producer was another. They had cut some demos at Cherokee Studios with the house engineer, but then went through a number of producers, including Eddie Kramer and Roy Thomas Baker, before deciding to produce the album themselves (mixed by Dennis Mackay), to which Jet agreed.

While they were putting the new band together, there was a very belated appearance in American record shops of Back On The Streets. There was no band to tour the album, and in any case it was music out of time because Gary had moved on. But the critics could only review what they had in front of them, and so while Gary’s guitar playing was highly praised, there were the inevitable comments about an album of two halves. But Cashbox called it “one of the more listenable efforts this year”, while another paper proclaimed that “the album is brutal. Moore has a command of his guitar that ranks with the great ones. He challenges all forms of contemporary energy music.”

There was an interesting if hilariously erroneous comment in the Rocky Mountain News, whose reporter opined that Gary was “a guy in terror of success”, citing as evidence the fact that he left both Skid Row “when the Irish group made its London breakthrough”, and Thin Lizzy twice “because of that band’s success”.

Gary was always anxious about his career, about what the next step should be. But what the reporter took for ‘terror’ was Gary wanting to do his own thing, play his music on his own terms, even if that was not always in his best interests. G-Force was arguably a case in point.

Mark Nauseef reckons “we had tunes from the time we recorded Back On The Streets at Morgan and in the Bahamas, plus the material we had been working on with Glenn that was already in shape – this power-soul direction – which maybe had the potential to be even more powerful because we now had Tony. And then somewhere in there they started to sound like pop – staccato eight-note things – and it was Gary that was bringing that in. Then the material started to change to fit that, and I thought we were starting to lose our way here.

Listening to those demos, including three from the session with Hughes, what you hear is a band shaping up towards being a no-nonsense hard rock band, but without sacrificing the melodic content inherent in Nauseef’s view of where the strength of the band should be. Although Sharon says “you couldn’t tell Gary what direction to take his music, he told you”, she and Jet were looking for a sound that would appeal Stateside.

Gary himself seemed unsure of what to do, as he told the UK paper Musicians Only in July 1980 after the album’s release: “I just wanted to get a band together that was a great band. I wasn’t really thinking about the direction or anything. I think at the time I was directing it at the American market.”

The self-titled album, released in May 1980, had much to commend it and was an important staging post in Gary’s career, eschewing the lack of coherence that had undermined his earlier work. Overall, G-Force was a comprehensive package of early-80s pop metal with high-grade musicianship, plenty of inventive and catchy riffs from Gary (especially on Because Of Your Love) and vibrant arrangements.

They foreshadowed both Gary’s own career for the rest of the decade and more general developments in music. White Knuckles (which segues into Rockin’ And Rollin’) appeared to be an answer to Eddie Van Halen’s Eruption and became a routine part of Gary’s repertoire.

There was a marriage of pop sensibilities and aggressive rock guitar across the album, a style that didn’t really capture the public imagination until 1983, when David Bowie released Let’s Dance, with a solo by Stevie Ray Vaughan, and Eddie Van Halen added a solo to another pop hit in the same year, Michael Jackson’s Beat It.

Coincidence? Maybe. Then again, perhaps somebody had been inspired by what Gary had served up. There was also a view that perhaps the album was over-produced, too many nods to ELO in the string arrangements, and that Gary had made a mistake in putting his guitar straight through the mixing desk, using a DI unit, giving it a synthesised, fuzzy sound rather than the hefty, crunching sound from a regular amplifier.

Gary was quite proud of this; as he told Musicians Only in the same interview, he had first come across the sound while working on Phil Lynott’s Sarah and on the G-Force album: “I was trying to get a distinctive sound and I think I have. I didn’t use amps on any of the solos, it’s all DI’d. The guitars have gone through overdrivers and things, but no amps. I found it was a really good way to get a sound that was upfront. You could do anything with it. And it’s all totally flat, with no EQ added to it.”

The choice of single was also debatable. It should have been the Tony Newton/Willie Dee composition You Kissed Me Sweetly – probably the most realised marriage of pop and driving rock styles on the album, and Dee’s best vocal performance – rather than Gary’s Hot Gossip. This song is worth a second look because, according to Gary’s girlfriend Lisa, the sentiments expressed exactly match what was going on in their relationship.

Once again, Gary was becoming obsessively jealous: ‘I don’t mind you going out with your friends, if it’s to places where we’ve both been/But I don’t like you going with him, don’t wanna have to say this again/I don’t mind you going out to a show, if it’s with people that we both know/But I don’t like you going with him, I’m gonna stop this before it begins.’ Even as early as March 1979, Lisa said that Gary had asked her to marry him, but she had written to her father to say that she wasn’t going to do anything rash.

“He was so jealous. If I was staring out into space in a pub, he’d accuse me of wanting to fuck some guy he thought I was staring at. He actually said: ‘I don’t mind you going out with your friends to a movie or a restaurant while I’m away, but I want to have seen the movie or been to that restaurant first.’” Lisa also claims that Gary told her the whole G-Force album was about her “fuckin’ around”.

It’s impossible to verify that claim, but certainly there are Gary compositions on the album that speak to the notion of a desperate infatuation, and on She’s Got You there’s a woman ‘so blond it tears you apart’.

In the company of Sharon Arden, Gary and Lisa were certainly living high on the hog. This was still what Don Arden calls, in his autobiography, Sharon’s ‘wild child’ years: impossibly expensive shopping trips, extravagant gifts of cars, furs and jewellery. She bought Lisa a black convertible sports car; mad parties at Don’s multimillion-dollar home; ludicrously overpriced meals in hip LA restaurants. Jet Records was also covering all of Gary and Lisa’s daily living expenses and all the expenses of the band during the long recording process of the album. Sharon was right behind the band.

“Gary and Sharon got on famously,” says Lisa. ‘The same sense of humour, both very witty and very naughty. Hysterical, really.” It wasn’t all bad between Gary and Lisa. “We would go into a Mexican restaurant where there would be a guitar entertainer, and Gary would ask to borrow a guitar, and it would be: ‘Oh no, no, no,’ because Gary looked like some kind of punk rocker. But then he would insist, and play the most amazing Spanish guitar. And the whole restaurant would be like: ‘Who’s that?!’ And that gave me the chills: ‘Oh my god, he’s so talented and he’s mine.’”

However, Gary and Lisa were not meant for each other; she was a party girl who enjoyed her freedom: “I couldn’t breathe. He was so jealous. It was awful. I thought if we got engaged he might lighten up. So he bought a ring on Sunset Boulevard and we got engaged. Really, though, I was in love with Steve Jones.”

As Glenn Hughes said, much of Gary’s LA social life was in the drinkers’ club – and that could easily get out of hand between Gary and Lisa, who was also rather fond of the coke. Their relationship was volatile, paranoid and dysfunctional. Lisa claims there was violence; she retaliated by cutting all Gary’s clothes up, causing thousands of pounds of damage.

Speaking to writer Chris Welch in 1982, Gary mentioned a Spanish guitar that got busted up by a girlfriend – and this could easily have been Lisa. Sometimes she would go and hide out at Sharon’s place: “She would let me stay but told me I had to go and sort things out.”

Things were no better when Gary moved back to London and the flat in Fitzjohn’s Avenue – more fighting, tears, food thrown against walls, desperate attempts by Gary at reconciliation. But Lisa’s approach to life and her lifestyle just made him too insecure and nervous. Eventually she fled back to LA, and that was that.

Gary had been here before. The last time he was trying to lead a band, there was all sorts of emotional turmoil in the background. And here he was again. And, like before, the band was starting to unravel. Strangely, for a band whose material was attempting to win over American music fans, there were no gigs in the USA at all – none of the material was road-tested, no private or low-key gigs anywhere.

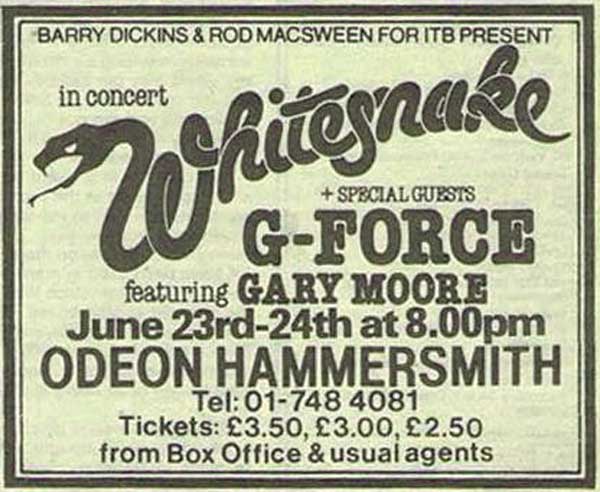

Tony Newton says there was discussion about the band doing some gigs under a different name before the album came out. Instead it was decided that the band would debut in England, on a tour supporting Whitesnake.

Guitarist Bernie Marsden was in Whitesnake at the time, and said he convinced everybody to put Gary on the tour: “I couldn’t believe it, nobody knew who he was. But they weren’t too pleased when Gary opened up and nearly blew the audience to hell and back with the volume.” But they couldn’t have been that displeased, because Whitesnake bassist Neil Murray says that in 1982, with the departure of guitarists Marsden and Micky Moody, David Coverdale was giving serious thought to asking Gary to join the band.

The album provided the bulk of the live set, plus Back On The Streets, Parisienne Walkways and Toughest Street In Town, one of the very rare occasions when Gary performed a Thin Lizzy song. They went down really well; many fans compared them very favourably with the headliners. “We kicked ass on the tour,” says Tony. “I think it was a matter of exposure; we had the musicians, Willie was singing his ass off, it had all the components. We were going for our own sound and, as far as I was concerned, we did a good job. Lots of hard work and energy went into that project.”

Gary later described the band live as “a disaster”, but that had to be more a reflection of his personal problem with Willie Dee, because live bootleg recordings belie any assertion that this band could not deliver the goods. Stripped of the LA studio pop gloss, they were a ferocious live act, and gave Whitesnake a run for their money.

Ultimately, though, nobody has a concrete explanation as to what happened, although there were strains and stresses that would have contributed to the demise of G-Force. Certainly, Jet’s enthusiasm was waning; Don Arden prided himself on how much he would spend on a band to make it successful. Jet had invested in G-Force in all departments but so far had seen no returns.

Mark Nauseef views it in very practical terms: “I think the answer as to why Jet pulled out of G-Force has a lot to do with Gary’s solo situation. Jet had signed Gary as a solo artist and released Back On The Streets in the US. So after the G-Force tour, I think Jet concluded that regardless of what they thought of other musicians in the band, they had to focus on Gary. I think for them G-Force was draining energy from Gary as a solo performer. Of course, Gary would need a band to continue touring and recording, but it didn’t need to be a band on retainers, et cetera.”

Gary had moved back to the UK, and would have known that Jet was not going to pay for him to fly backwards and forwards. This was his way of signing off on the band without having to endure a sit-down meeting. Sharon, too, was beginning to put her considerable energies elsewhere – towards Ozzy Osbourne.

Sharon and Ozzy first met in 1974 when Don took over management of Black Sabbath. When Ozzy was kicked out of Sabbath in 1979, he signed with Sharon for management. Trying to launch Ozzy’s solo career, she enlisted the help of G-Force.

Mark recalls: “We tried out some material with him, got him up and running, trying to get the first album together. We wrote some material, rehearsed it at Zappa’s place. We were really slamming behind him and he was up for working with us. Gary would start with an intro and as usual he would really go for it, playing like it was his last day on earth. And then we would get to the vocal, and Ozzy would just stand there and say: ‘Now what do I do?’

He was so sweet and humble, just standing there listening to the way we were playing. We said we could lay back a bit, cool it down and he said: ‘No, man, this is great.’ He was so positive about it all. And then I’d see Sharon in the evening, put a cassette in the car and she’d go: ‘Yes, this is it.’” But, wanting to see his kids, Ozzy suddenly jumped on a plane and headed back home, which put an end to their collaboration.

“We got paid, got given handmade luggage as presents,” Mark says, “but we were disappointed that we weren’t going to be involved in recording the album.” However, the thought of Gary trying to work with Ozzy on any sort of regular basis makes you wince. He quite rightly turned down the offer to be the guitarist in Ozzy’s band, the spot taken by Randy Rhoads. There was an in-joke among Gary’s Jet Record label companions that if Gary had got closer with Sharon, his future career may have panned out very differently.

So, Ozzy may have helped distract Sharon away from G-Force both professionally and emotionally. Then there was Willie Dee. He was finding the environment very challenging. Interviewed for a Captain Beyond fan site, he said: “I went through all this fiasco with Sharon and G-Force… it was a real nightmare because Sharon wanted to do really pop stuff. And I really didn’t want to do pop stuff.” He claimed too that “me and Gary hated each other” – and the whole situation drove him to a nervous breakdown.

Pondering this, Mark Nauseef observes: “Whatever his beefs were/are with the G-Force situation, I think he was offered a reasonable opportunity, and no doubt there was a lot of attitude in that band, but I’m not sure how and why he perceived his situation to the point of ‘nervous breakdown’. Gary could definitely have some edge, and he would sometimes push the musicians he worked with.

"He also had no hangup about letting others know that he wasn’t pleased with their contributions. But I think he only did that with the musicians he thought had the potential to deliver. He simply wouldn’t take the time to challenge someone who didn’t have the goods or he didn’t respect. Willie sang great on the record, and that was Gary pulling it out of him.”

But Mark also suggests that with Gary – and with Tony, given his pedigree – maybe there was an overdrive to perfection that Willie found hard to handle. In any case, if the singer is not the leader of the band, then there is every chance that the leader – in this case most definitely Gary – would be telling him what to do and how to perform, none of which would sit easily with most singers.

Mark talks about “attitude in the band” and, for sure, Tony Newton, with all the depth and breadth of his experience, wanted his say: “My understanding was that it was a group project rather than Gary’s band per se.”

Tony goes on to vent his criticism at the way the album sounded because of Gary’s insistence on how the guitar would be recorded: “He was thinking that it would give it a unique sound. And it did give it a unique sound – a horrible, scratchy, piece-of-shit sound. Going through the board destroyed the fidelity of the album.”

Gary himself backtracked in another interview, saying that while to his ears it sounded great in the studio, “it didn’t transfer too well to vinyl and I was a bit disappointed in the end result… It wasn’t warm enough and sounded totally detached from the backing tracks.”

Tony is also quite critical of some of the musicians Gary subsequently had in his band, saying that he and Mark Nauseef were at a different level to those he describes as “generic’ sidemen”. He goes on to to say: “I was surprised that Gary didn’t have great musicians in his band, that he didn’t have the wisdom to know that if you do that, you’re better. I think maybe he just didn’t know how to deal with people like that.”

In Tony’s opinion, because of that, “he was a fantastic composer and guitarist who rose to greatness, but my take anyway is that he didn’t reach his potential”. And given Gary’s clashes with star musicians who were band leaders in their own right, like Phil Lynott, Glenn Hughes and later Cozy Powell, he might have a point.

The band didn’t so much end as fizzle out. Tony says they were all on a weekly wage, “and it just stopped. But nobody got a call. I eventually got in touch with Don Arden, had a meeting and he said he didn’t know what he was going to do with Gary.”

Sharon looks to Gary for an explanation: “Gary and I spent a lot of time together, socially. I can’t remember any specifics, but Gary was always dissatisfied. Not finding the right singer was a big stumbling block for Gary. But in the end he didn’t need a frontman – he was the frontman. And he wanted to be bigger, he wanted to be more. Nothing was ever right, and that’s being an ambitious musician. He wasn’t where he wanted to be.”

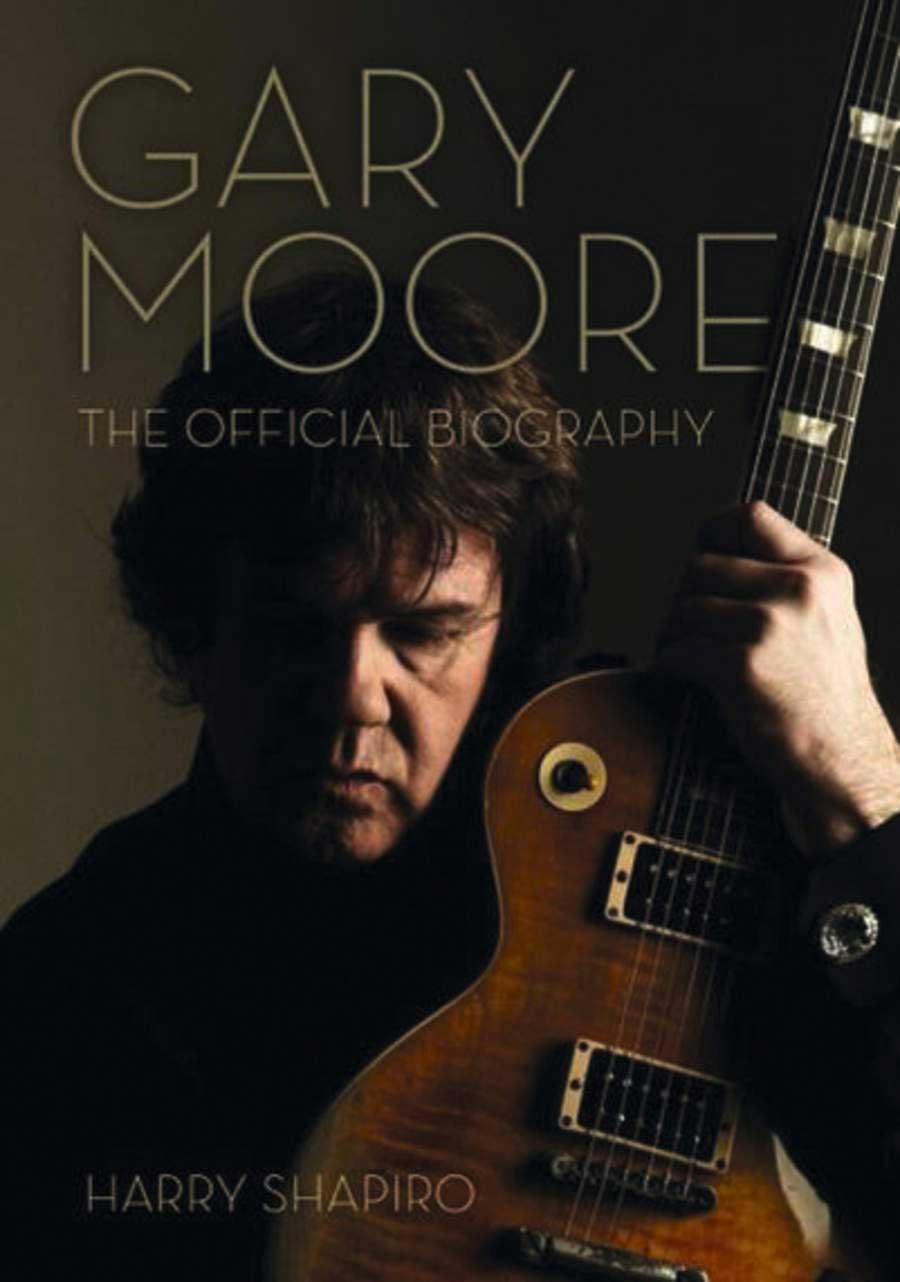

This exclusive extract is taken from Gary Moore: The Official Biography by Harry Shapiro, published by Jawbone on September 27. Reprinted with kind permission.

Harry Shapiro has been a writer, journalist and editor for over forty years specialising in all aspects of drug use and addiction and also popular music – rock, jazz and blues. He has an extensive portfolio of books and articles – from popular biography and books for young people through to peer-reviewed academic journal articles. He is also the Director of DrugWise, an online drug information service, and active in the world of tobacco harm reduction through the Global Forum on Nicotine. He is the author of Jimi Hendrix: Electric Gypsy, Eric Clapton: Lost in the Blues, Waiting for the Man: the Story of Drugs and Popular Music and many other titles.